Montparnasse, 1893 – 1914

By the 1880s, artists from all over the globe were settling into studios and apartments in Paris, particularly in Montparnasse. This included large numbers of American artists, both men and women, who were drawn to Paris, leading one scholar to claim that “the most innovative work being done by Americans in the years from about 1907 through 1913 was created in Paris" (Mecklenburg 250).

Although foreign students came to Paris for other studies too (especially medicine [...], by far the largest number were students of fine art, for whom the French capital was routinely described as a Mecca. Its supremacy had emerged gradually during the century. One of the earliest attractions was the Louvre, with its collections of artworks, many of them the fruits of Napoleonic conquests. But Paris could also offer a uniquely dense concentration of artists, teachers and studios, and the long-established annual exhibitions, known as ‘Salons’, offered a pathway to recognition, as did the various ‘alternative’ Salons of the later years of the century (Reynolds 57).

Art Academies

The Art Academies

The immediate neighborhood surrounding the Girls’ Art Club was a haven for artists and Americans.

The rue Léopold Robert, across the boulevard du Montparnasse from the rue de Chevreuse, had been literally transformed into an American enclave of restaurants, boutiques, and bakeries:

All parts of the United States are represented in Robert Street. Families from New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, are most numerous there. They live together intimately and learn to bear with one another's pride in their native city. There is a gather of the Americans nearly every evening in the week in one of the Robert-street drawing-rooms [...] They are here for a different purpose from the Americans who live on the other side of the river, called "The American Colony." The Robert-street Americans are in Paris to study, or allow their children to study, painting or sculpture, or the French language and literature. The average length of stay is two years, though some remain four or five years (Turpin B2).

The rue de la Grande Chaumière behind the Club, which had been officially traced in 1830, was home to numerous artists and art schools. In 1841, the first artist to move his residence and studio to this street was the sculptor Étienne-Hippolyte Maindron, who initiated a wave of other artist settlers. In 1871, Paul Cézanne briefly stayed at 5 rue de Chevreuse, near the landscapist Johan Jongkind, who had moved into a studio on the corner in 1861. By the 1890s, the adjacent rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs “[…] had long won its title as the ‘royal road of painting,” its houses all occupied by one or more bemedaled, and often knighted, professional artists (Crombie 1998, 19). There were many studio enclaves up and down the adjacent streets. Sculptor Joseph Caillé, stained-glass worker Eugène Oudinot (whose dilapidated atelier at 6 rue de la Grande Chaumière was taken over and fully renovated by Félix Gaudin in the late 1880s), photographer Charles Marville, painter Gustave Courbet, academician William Bouguereau, and portraitist Carolus-Duran were all based in this area. In the following decades, a host of expatriate artists followed James Abbott McNeil Whistler’s early forays into the Latin Quarter. John Singer Sargent, Elisabeth Jane Gardner, Anna Klumpke, and many more settled in the Art Club’s vicinity. More artists would flock to the neighborhood in the 20th century, including the women who once resided at 4 rue de Chevreuse and later, like Elizabeth Nourse and Janet Scudder, moved to their own studios nearby.

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, private workshops and atelier-style art schools were established in and around Montparnasse as a sort of protest against the official academic styles favored by more traditional institutions. There were no doctrines or clichés at these new schools, just the simple goal of inspiring each student to achieve greatness. Budding artists worked with live models, male or female, and received indispensable technical and critical advice from celebrated artists who also gave private lessons in their own ateliers. Most importantly, especially for residents at the Girls’ Art Club, these new schools accepted women without prejudice (the École des Beaux-Arts only began admitting women around 1897). "Invigorated by a sense of shared experience, by friendships and rivalries with fellow women students, they saw it as the means to achieve their own art practice as professionals on par with their male colleagues" (Butlin 51).

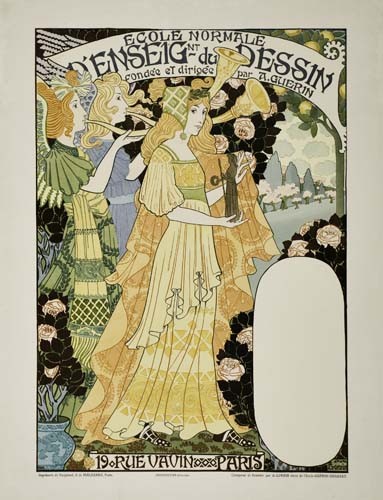

The five académies highlighted on this page were frequented by Girls’ Art Club affiliates – the careers of many women artists were launched after studying at these institutions. They are just a few examples of the abundance of neighborhood academies that popped up during this period. Whistler installed his short-lived Académie Carmen, a favorite with American women students, in the passage Stanislas. It opened in 1898 but closed a short time later in 1901. Sculptor Frederick MacMonnies taught life drawing classes at the Académie Carmen for one year. Another atelier-school was founded on the corner of rue Vavin and rue Bréa by the architect Alphonse Théodore Guérin in 1881. Officially named the École normale d’enseignement du dessin, the school offered courses in anatomy, design, and perspective, aimed at students who were interested in pursuing a career in industrial design. Guérin stayed on as the school's president through at least 1899. It is difficult to determine how long it remained open, though Crombie suggests that it was taken over by the Lefebvre-Foinet art supply store (1998, 42), which was established around 1904.

Académie Colarossi

This private school originated on quai des Orfèvres in 1815. It was founded by M. Suisse, who sold it to a man named Cabressol, who then sold it to the famous Italian model and sculptor, Filippo Colarossi. Colarossi moved the school to 10 rue de la Grande Chaumière in the 1870s, the first of its kind on the street. The academy also rented studios and rooms to artists around the courtyard (Crombie 1998, 29).

Many renowned artists advised and critiqued Colarossi’s students. In 1902, one of the Girls' Art Club's residents, Geraldine Rowland, characterized the atmosphere at Académie Colarossi:

A large sign over the doorway indicates its presence, or it might be passed by so easily, so unpretentious is the exterior, and so dilapidated and shabby the rooms within. [...] Invariably, of both men and women, the sketch class presents a heterogeneous gathering. It is wholly unconventional. Those who come early make themselves comfortable in the best positions, while others who are late must be content with some vacant stool which affords and oblique and difficult view of the model. She usually comes in last of all. Finally the clock strikes, and she takes a position. [...] and then, for some twenty minutes, not a sound is heard except for the scratching of many crayons over the paper's surface. During the time four different poses are presented. [...] To this class there is no initiation fee, neither do masters come in to give criticisms. The obligation is paid by simply placing fifty centimes in the plate held by a white-smocked individual who stands near the entrance to the courtyard (758-759).

Initially, Raphaël Collin and Gustave Courtois, two Salon painters, taught figure drawing and painting, while Jean Antoine Injalbert headed the sculpture studio. Rowland enrolled in Collin's atelier as well as the outdoor class he taught in his garden at Fontenay-aux-Roses:

It is Monsieur Collin who has a fondness for painting out-of-doors where the sunlight can find the opalescent tints of the flesh [...]. In his garden [...] there are many flowers, gay in spirit, rich in color; and also there is a secluded corner enclosed by a high wall which might well perplex even a Peeping Tom. Here, during the summer, M. Collin instructs a class. Usually, it boasts several American girls (760).

In 1900, Czech painter Alphonse Maria Mucha began offering drawing classes, the "Cours Mucha," at Colarossi. Known for his Art Nouveau style, Mucha was also responsible for the storefront design of the legendary crèmerie, Chez Charlotte, at 13 rue de la Grande Chaumière. In 1910, Colarossi hired New Zealand painter Frances Hodgkins to teach watercolor classes; she was the Academy's first female instructor, but only stayed one year.

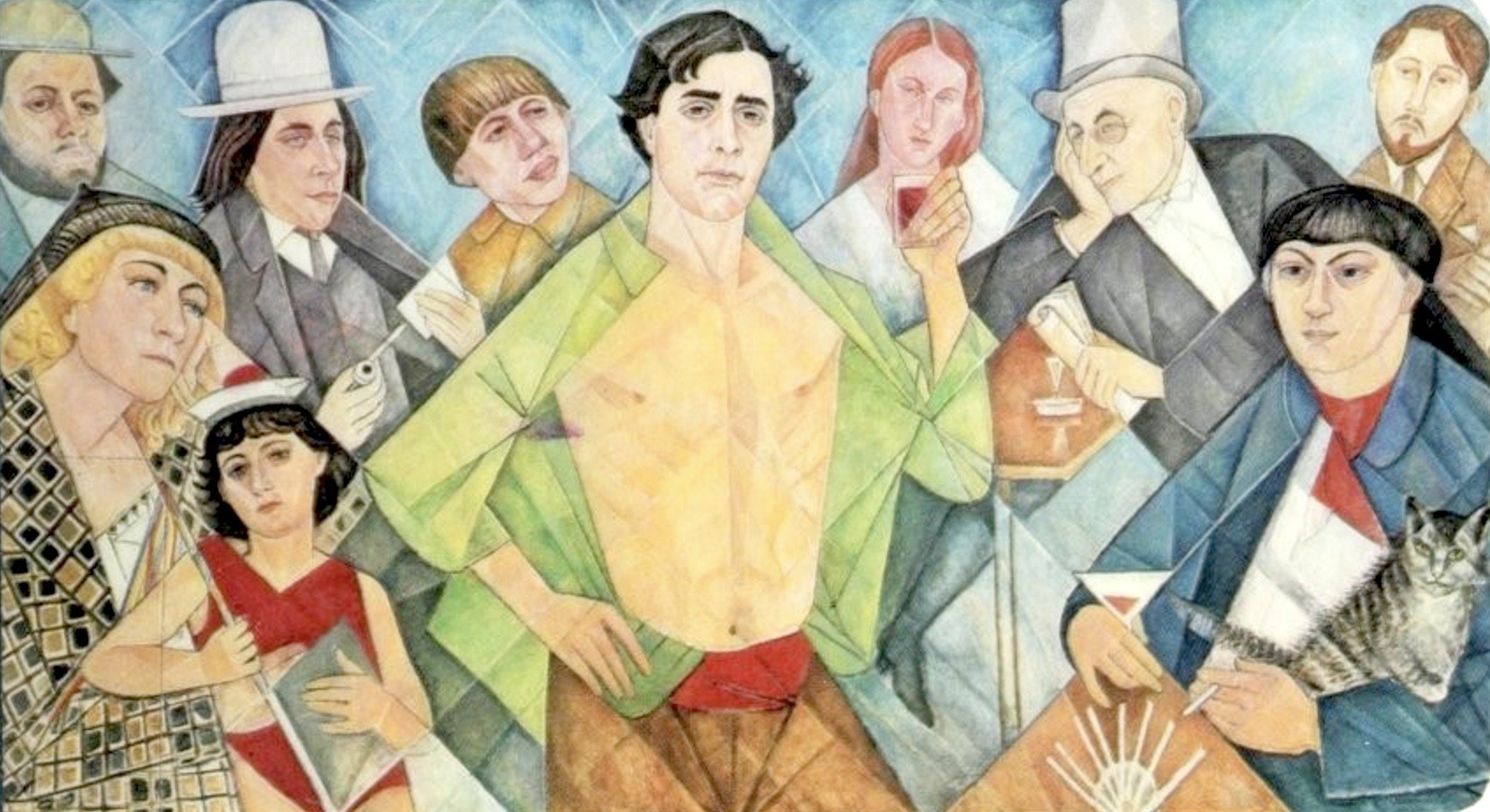

Artists from many parts of the world attended classes or painted at Colarossi. The list of notable graduates is impressive and includes: Camille Claudel, Jeanne Hébuterne, Bessie MacNicol, Edvard Munch, Amedeo Modigliani, Henry Moore, and Janet Scudder. Colarossi's annual Bal d'hiver (Winter Ball) was one of the most joyous and raucous events in Montparnasse.

The academy closed in the 1930s and Colarossi's wife supposedly burned the entire archives of the school in retaliation for her husband's philandering.

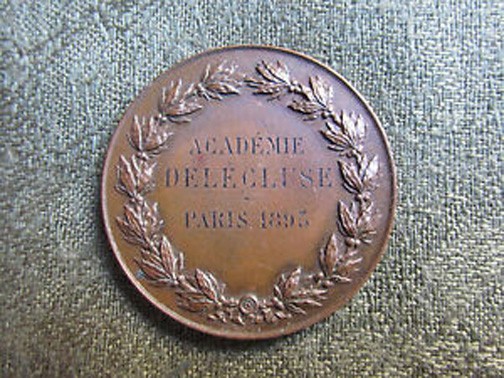

Académie Delécluse

This art school was founded in the late-19th century by painter Auguste Joseph Delécluse (1855 – 1928). Regarded as one of the more reactionary and cutting-edge ateliers, it was especially popular among young American women, particularly because more space was given to women than men. Canadian painter Florence Carlyle happened upon the first Delécluse studio in the basement of a building and decided to enroll; she preferred its relaxed atmosphere to the severe criticism of Bouguereau at the rival Académie Julian. Carlyle’s enthusiasm and that of her friends brought more women students to the atelier, which enabled the academy to move to bigger quarters in the attic of a building at 84 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs (Butlin 44). Teachers included Georges Callot (1857 – 1903) and Paul Delance (1848 – 1924). Among the famous students were Harold Harvey and Simon Elwes.

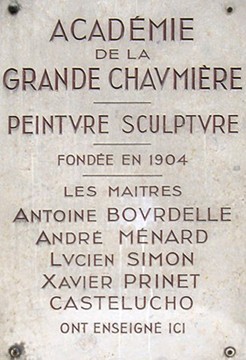

Académie de la Grande Chaumière

Founded in 1904 by Swiss national Martha Stettler (1870 – 1946), this académie is still open and maintains a spirit of total independence from mainstream artistic currents. A last remnant of the heyday of Montparnasse, this atelier, which measures 512 square meters, still bathes in the glow of its past, with wooden stools, easels, and drawing tables covered with paint. A scent of turpentine permeates the room:

Today, the heating is electric, but that seems to be the only change. Atmospheric and inspirational, the light filters in from the large, north facing windows that extend along an entire wall (Della Drees personal website).

Illustrious former teachers include Antoine Emile Bourdelle, Jacques Emile Blanche, Othon Friesz, Lucien Simon, Fernand Léger, André L'hote, and Ossip Zadkine. The list of students is equally impressive: Alexander Calder, Tamara de Lempicka, Alberto Giacometti, Isabel Rawsthorne, Amedeo Modigliani, Serge Poliakoff, Nano Reid, Balthus, Joan Miró, and many others.

Sculptor Angela Gregory, who lived at 4 rue de Chevreuse in 1927, described the atmosphere of the Académie in her memoir, A Dream and A Chisel:

The Grande Chaumière was totally different from any art school I had ever attended. At Newcomb and Parsons you had to be there at a certain hour to paint or at a certain hour to sketch and the instructor was always there to direct you. At the Chaumière, however, nobody leaned over your shoulder. You went whenever you wished, knowing that during certain hours there would be a model posing. In the beginning, I was a bit lost in such an unstructured environment. I mostly learned by myself or by watching the other students. Nobody came over and said, “You should do it this way or that way.” [...] The Académie de la Grande Chaumière had been created so that young artists who could not afford a studio of their own could come work and receive an occasional critique from an established artist such as Bourdelle. The creative atmosphere was thrilling and intense. If the model was posing you never heard a sound. No one was chattering away or making jokes. Everyone was very serious. There was a monitor, Madame Lavrillier,11 who helped to keep things organized and who made sure there were enough stands for modeling, enough clay, and that the model was there to pose (68).

In 1957, the school was taken over by the Charpentier family, who continued its traditions and mission. Upon the death of the last owner in 2018, the atelier’s building was turned over to several associations who have tragically contemplated selling various parts of it. Since it is not landmarked as a historic monument, its integrity and future are currently in jeopardy.

Académie Julian

In 1868, Rodolphe Julian decided to transform his own studio in the Passage des Panoramas into an atelier that could accommodate at least 50 other artists. He conceived this studio as an “école libre,” where anyone could paint from a live model. He opened without a single student, yet, every day, he would have a model (often Italian) pose for the empty easels and seats. This lasted for about 4 months until someone walked in by chance and stayed. Eventually, word of mouth increased the number of participants, but the first four years of his experiment were challenging (Debans 185-212).

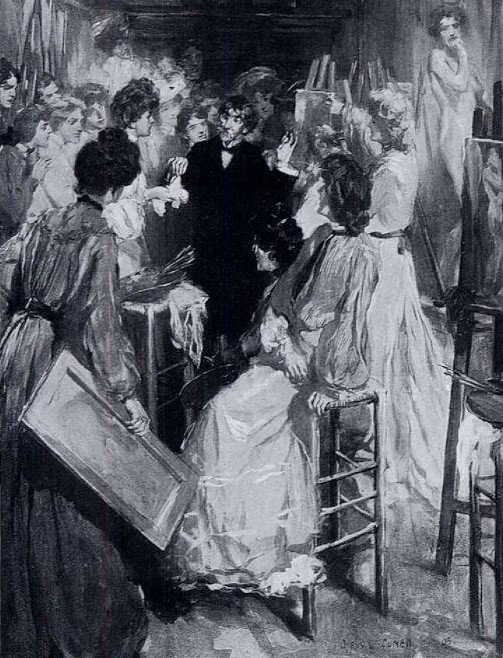

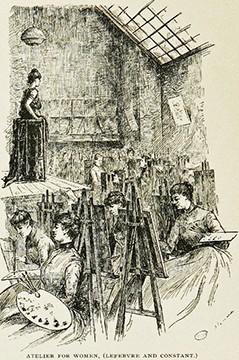

Julian then decided to open his studio to the growing number of women artists in Paris. At first, artists evaluated each other’s work at the Académie Julian in an atmosphere of emulation and camaraderie. Eventually, he invited “masters” to critique the students as they worked: William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Gustave Boulanger, Tony Robert-Fleury, Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Henri Chapu (for sculpture), and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. The Académie became so popular that he opened another studio on Faubourg Saint-Denis for men, while the Passage became a studio exclusively for women. He also opened another studio for women at 5 rue de Berry (8th arrondissement). The masters would make regular rounds at each location. In 1895, Julian married Amélie Beaury Saurel, a well-respected portraitist from Spain, and named her director of the Passage studio.

According to Riccardo Nobili: "The atelier for women is truly a fortress of the Amazons. No soul of the other sex is allowed to pass the portal, save Monsieur Julian, the masters, the models and the dealers in colors. Even the fathers and brothers who accompany the ladies to the door, are compelled to leave them" (751). In the Passage and Berry studios, the models were almost always women.

Debans described the layout of the women's studio: the posing table was set in the middle, with students seated all around. Each Monday, places were available on a first-come-first-served basis and each woman retained her place for the rest of the week (196). Nobili described the manner of selecting models: "The candidate disrobes and mounts the pedestal, taking many different positions. The 'massier' (a student at the head of the school), takes a vote of the pupils amid a noise and confusion that is indescribable. If the majority approve, the model is employed" (748), and usually remained for eight hours. Each hour, the artists would work for 45 minutes and then take a 15-minute break.

Twice a week, the masters would evaluate each student’s work. “The days on which they appear are great days. All these ladies, completely filled with emotion, follow them from easel to easel, drink, so to speak, their reflections and advice, and sometimes push self-defiance to the point of stenographing their words” (Debans 197-198). When the master had finished his rounds, he would be surrounded by women holding canvases they hoped to exhibit at the Salon (Debans 199). In her Memoirs of an Artist, American painter Anna Elisabeth Klumpke recalled her experiences at the school during her year of study, 1883 – 1884:

Monsieur Tony Robert-Fleury was the director of the class. He came early in the morning - never later than half past eight on Friday and Saturday. There were no formal introductions. He inquired where one had studied. His corrections to each student were very brief, especially if the work seemed to him of little interest. His corrections were given in a loud voice as if for the benefit of all as well as the individual to whose work they applied. He went from easel to easel seeming to take in at a glance the measurable ability of each worker and our awe of him... was manifested by the intense silence as he went his rounds... (16).

Among the masters, Bouguereau was preferred because he mixed his critiques with encouraging words and he regularly invited students into his own atelier on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Robert-Fleury was the least severe; he spoke simply and kindly. Lefebvre, on the other hand, was the coldest of the three, but everyone believed he spoke the truth about their practice; they also appreciated his ability to remember the names and works of each student (Debans 200).

Over time, Julian opened two other branches at 28 boulevard St-Jacques (6th arrondissement) and 31 Rue du Dragon (6th arrondissement). He also began sponsoring monthly competitions among the different studios, awarding medals and a small prize of 100 francs to the winners (Debans 201). His instructors and students often served as jurors at the various Salons. Controversies arose regarding the impartiality of these jurors, who were said to favor artists from their own school: "professors and some students supported each other in the elections to the Salon jury and in the distribution of prizes" (Greer 52).

Over the years, the Académie Julian attracted an extraordinary array of international students and teachers who would enjoy successful careers. Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard were students, as were Boris Anrep, Jean Arp, Cecilia Beaux, Thomas Hart Benton, Maurice Denis, Jean Dubuffet, Marcel Duchamp, Anthony Gross, Childe Hassam, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Henri Matisse, John Singer Sargent, James Wilson Morrice, Robert Rauschenberg, Diego Rivera, Jacques Villon, Grant Wood, and so many others. See the alphabetical list of artists, both students and masters.

Académie Vitti

Located at 49 boulevard du Montparnasse, the Académie Vitt was among the first to accept female art students. It was founded in 1889 by Cesare Vitti, his wife Maria Caira (who spoke English), and her sisters. They had left Italy to become professional models and painters in Paris. The family returned to Italy at the outbreak of World War I and the school closed in 1914. In 2013, Vitti's grandson opened a museum in Atina commemorating the academy and affiliated artists. Paul Gauguin, Luc-Olivier Merson, Frederick MacMonnies, and Kees Van Dongen were among the many instructors.

The Académie also served as a meeting place for students in the Latin Quarter. Beginning in 1893, it was the site of the “Students’ Atelier Reunions,” an initiative serving the spiritual and social needs of American art students in the neighborhood. The sermon was followed by a musical program (McProud, 93-94). Marguerite Thompson Zorach detailed the vibrant atmosphere at its Sunday services:

Sunday nights you go to church in the famous Vitti studio. The entrance is through a narrow, gloomy passage marked by an electric sign "garage" in red letters. When you are beginning to wonder what sort of place you have gotten into and how you are ever going to find your way out, a group of students who have come in behind, open a mysterious door to the left and you follow them through queer winding passages where a smelly little lamp coaxes you up one more flight of narrow stairs into the sawdust strewn entrance to the Vitti, itself, as are most of the great studios of Paris, it is a great barn-like place, an atelier in the true meaning of the word. The walls are gray with daubs paint and crowds of Adams and Eves, masterpieces left behind by the generous students, but with a few exceptions carefully turned to the lest they distract the mind of the congregation. These Sunday meetings at the Vitti are very popular. Rain or shine, all the English-speaking student world is there, perched upon all sizes of drawing stools from the tiny ones used for the front row in the portrait class to the tall ones for the latecomers in the evening croquis (sketch class). It is certainly a unique service, given from the model stand; sometimes when the speaker becomes excited, you wonder what would happen if he stepped beyond his little circle into space. On one side of him stands a plaster cast of one of Sir Joshua Reynolds' little angel heads; on the other, the monstrous head of a horse, his teeth bared viciously and his upper lip missing; below, rows of palettes and paint aprons remind one of the ambitious students who struggle here all week. Marie Antoinette, the pretty little black-eyed daughter of the janitor distributes the books and you sing the old familiar hymns you have known since you sat in the infant class of the Sunday school in America. But that is not all, there is also a program furnished by some two of the celebrities of Paris. It may be the leading violinist of the Grand Opéra or one of the promising young students who has just "arrived” in her particular line. Everyone is most kind in giving his services and his best efforts are always rewarded by a burst of applause usually swelling into a persistent encore. You quite forget for a that it is a religious service, but are brought back when the minister ascends the model stand for his address. After the closing prayer, you hurry home, but too late, the door is locked and you have to hammer violently until the concierge pulls the cord to let you in (Burk 93).

Artist Haunts

Cafés and Brasseries

Many watering holes in Montparnasse served as intellectual hubs for artists, models, and literati. They were regulars at one or several eateries, often trading their work for meals. Famous among these hotspots were the Closerie des Lilas, Le Dome, and La Rotonde, whose decor today hearkens back to that Belle époque. By 1919, some of the cafés were staging their own art exhibitions, and "there was quite a colony of artists whose life centered around the Café de la Rotonde, then the only drinking place of importance in the neighborhood" (Morrill Cody 13). As Georges Viaud, the resident historian of La Coupole, exclaimed: "if their tables could speak, they would tell the role of (these places) in the history of art of the twentieth century" (read the article on the Coupole's myths).

Chez Charlotte

In the 1890s and early 1900s, an impressive group of artists gathered at the crèmerie known as Chez Charlotte, a small restaurant and hostel at 13 rue de la Grande Chaumière. Charlotte Futterer, exiled from her native Alsace, which had been annexed by Germany in 1871, opened her crèmerie two years after the Académie Colarossi was established on the street. Charlotte's clients were students, models, and teachers from the neighborhood.

The crèmerie was like beehive buzzing with creativity, where artistic relationships and networks were formed. Regulars at Chez Charlotte included: Alphonse Mucha (who resided in an upstairs room for about eight years), Paul Gauguin, August Strindberg, Frederick Delius, Paquo Diurio, Wladyslaw Slewinski, and Edvard Munch among others (Crombie 1998, 24).

Mucha painted the left metal panel of the facade, and he collaborated with Wladyslaw Slewinski on the right panel. The wall in the courtyard at the back was decorated with a large fresco representing the Luxembourg gardens painted by Stanislas Wyspianski (Gutman-Hanhivaara).

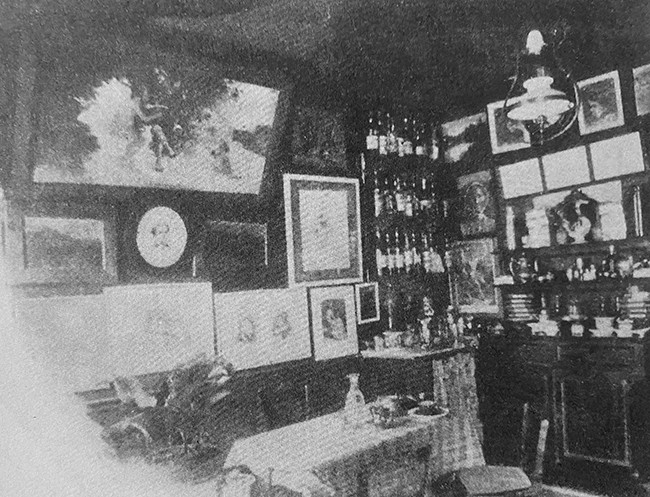

The tiny creamery was an unusual place. It included a room that could accommodate at most ten guests and a kitchen, often crowded with people, which gave access to a small courtyard where the toilets were located. Madame Charlotte lived with her son in a small apartment above the restaurant and rented the other rooms, most often to impecunious artists to whom she also served meals. Also the creamery was lined with works offered to the one who called herself ‘the mother of artists’ in debt settlement, or which she had bought to help her residents (translated from French, Gutman-Hanhivaara 90).

Charlotte closed the crèmerie in 1902 and retired to the town of Noyon with the large collection of paintings she had collected over the years (Crombie 1998, 40).

Chez Rosalie

Chez Rosalie was established at 3 rue Campagne-Première by Bouguereau's former model, Rosalia Tobia.

Born Teresa Anna Amidani in Italy on March 13, 1860, she came to Montparnasse sometime between 1883 and 1887, working as a maid for princess Ruspoli then Odilon Redon and Auguste Renoir. On June 18, 1887, she married Giovanni Tobia, professional model for painters and supposed cousin of Filippo Colarossi, with whom she had a son in July of that same year. Records indicate that Rosalie turned to modeling for such artists as William Bouguereau (see "Rêverie sur le seuil" (1893), and "Jeunesse" (1893), Gustave Carolus-Duran, James Whistler, and many others.

In 1912, she invested in a small crèmerie (qualified as Lilliputian) on the rue de Campagne Première, transforming it into a restaurant. A New York Herald article dated May 16, 1926 described the humble eatery where she served spaghetti and chianti with “a heart that was as ample as her figure”:

[…] one small room with a minuscule zinc-covered bar squeezed in the corner, sawdust on the floor, tables innocent of coverings, cracked dishes of heterogeneous pattern, stools instead of chairs, on the wall […] a wild-eyed portrait in the new manner, a still life, the fat pink pigs of a circus merry-go-round in mad swirl (D12).

Chez Rosalie’s was very popular with blue collar workers, artists, and expats who appreciated its delicious, cheap, Italian cuisine. Among the regulars were Modigliani (who painted her portrait), Utrillo (who painted a fresco with Modigliani on the restaurant wall), Edvard Diriks, and the poets Fort and Salmon. In her mémoires, Kiki de Montparnasse, mentions eating at Rosalie's: “I used to go to Rosalie’s to eat, in the rue Campagne-Première. There, I’d order soup" (119) – a minestrone she sold for 6 sous. Many exchanged a painting or drawing for nourishment in this tiny, convivial place with four tables.

According to Crespelle, “Modigliani quickly became the master of terror in the place. Like all alcoholics, he was never hungry, and went there to find an Italian atmosphere. His great delight was to provoke Rosalie to anger and make her shout out insults in the most delicious form of popular slang” (72-73).

Rosalie kept the restaurant open for many years, though she sold it twice but bought it back each time (Hansen 147-148). She finally sold it for good at the end of 1932 and retired at Cagnes-Sur-Mer. She died at the age of 75 in December of that same year. An obituary in L'Écho de Paris reported that Montparnasse artists had just lost the one they called "maman" ( 2).

Margaret Butler, sculptor residing at the Girls' Club, was a regular Chez Rosalie. She sculpted and cast a bronze bust of this colorful figure of the Montparnasse community. Her outsized presence generated many a legend, which editor Patrice Cotensin discusses in his 2023 publication, Rosalie de Montparnasse, 1912-1932.

Chez Henriette

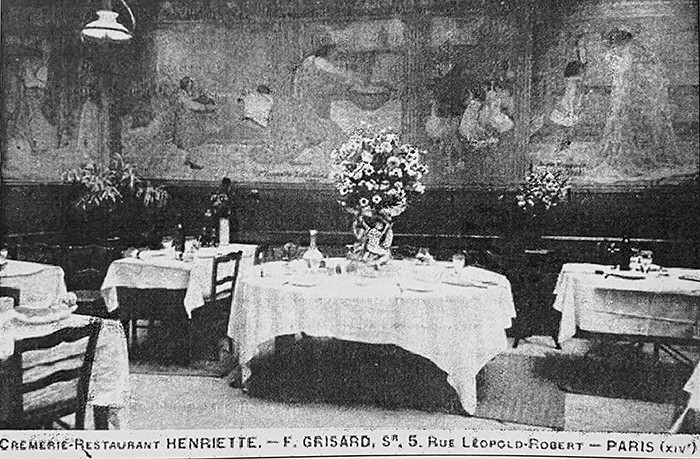

The best description of Chez Henriette (also called La Reine Blanche, Ottawa Citizen), the favorite gathering place for art students at the turn of the century (5 rue Léopold Robert), is provided by Katharine de Forest's July 7, 1900 article on student life in Paris for Harper's Bazaar:

There is no more typical spot in Paris than [...] Henriette’s. It is an ordinary creamery at first glance, and a particularly tiny one at that. Half a dozen people would perhaps stand with difficulty before the little counter on which are displayed with French daintiness the eggs, fresh pats of butter, and fromage à la crème which, mixed with vivid color in tomatoes and strawberries, the Parisian knows how to make so extraordinarily decorative. The walls are covered with Cheret posters, among which glare out here and there with astonishing incongruity the English words of some American bill […]

At one end of the little room is a door. It leads to a rambling passage hung with sketches in color and pen and ink, with a suggestive rack of numbered pigeon-holes, each containing a napkin in a ring, and then at the end the full splendor of the Restaurant Henriette suddenly bursts upon you.

The place is light, airy, French. Upon each of the little tables there are flowers. But what makes the place celebrated is the really beautiful frescoes on the walls, done by two American girls, Miss Florence Lundborg of San Francisco, and Miss Alice Mumford of Philadelphia. They represent the ancient but ever fascinating history of the Queen of Tarts, and nothing of the kind could be more distinguished and charming in both conception and execution than this procession of scenes over which hangs the quaint old rhyme. Go to Henriette’s, in the rue Leopold Robert, almost directly opposite the street in which is the Girls’ Club, and you will at once see the best of American Latin Quarter bohemia (630-631).

In the same article, de Forest also lists the daily menu:

As for food, here is the scale of prices on a daily menu picked up this week at the famous Henriette’s: cutlet, 50 centimes (10 cents); beefsteak, 50 centimes; rabbit, 50; mackerel, 50; Fried potatoes, 20; salad (price not given, probably 20); fromage à la crème (cream cheese), 25; rice pudding, 25; strawberries, 25; prunes, 25; coffee, 25 (630).

A New York Herald Tribune article tells us in 1926 that Henriette abandoned the restaurant some thirty years after she had founded it: “She had a passion for the Lottery. The slower surer rewards of her trade were too prosaic for her daring soul […] One fine day she found she held the lucky number. So Henriette departed to a more luxurious life” (D12).

In 2021, Chez Henriette is the site of an Italian restaurant, "Il Barone," and the frescoes are no longer visible, though the layout of the restaurant is the same and the above photo is proudly displayed to diners.

The interior of the beloved crèmerie was decorated by two residents of the Girls’ Art Club, Florence Lundborg and Alice Mumford, in 1899. Like so many other artists in the neighborhood, they were regulars at the small cremerie located steps away from the Club. A 1920 article in the Baltimore Sun explained that Lundborg submitted the idea of painting the barren walls of the restaurant in exchange for food: “Why not turn our art into food? Let’s decorate the walls and for our pay – eat” (A14).

Lundborg and her fellow artists decided to organize an anonymous drawing contest to determine who would be selected. Lundborg won the competition (San Francisco Chronicle, February 5, 1899) with a drawing whose Queen of Hearts theme came across as most fitting to the context. She harnessed the help of Alice Mumford and in, common accord with the owners Mme Paulain and her daughter Henriette, they began decorating the walls of the restaurant:

So, with pencil, paint, and brush the girls set to their task and day by day the story made its way across the walls. Hard work it was, and tiresome too, and if ever artists earned their bread, it was those two girls who wielded their brushes from scaffold and stool. Eight long panels it required, panels in colors light and dark, with its word story told in painted, printed words along the top of the wall. At last it was completed, and the cheery room became more cheery for the colorful story of “The Queen of Hearts who made some tarts” had developed into a work of real art (A14).

The colorful mural, complete with gold-leaf lettering and life-size figures extending over the four walls of the restaurant, was finished a year later. Mme Paulain staged a banquet in honor of the two artists, to which she invited 26 guests:

And when Miss Lundborg returned to Paris, after a brief vacation, she found upon her arrival at the café table specially arranged for her. It was resplendent with bright, new silverware, the finest of white linens, and trailing roses, which, in Paris, represent a small fortune (San Francisco Chronicle, September 2, 1900, 27).

The very same article remarks on the impact of the murals on the popularity of the restaurant: “People come in hordes from all over Paris and outside of Paris to view the unique decoration and the patronage of the place has been more than doubled” (27).

Years later, the new owner of the restaurant, a certain Monsieur Ribaut, wanted to restore the fading frescoes but only if the original artist could be found. He raised a hue and cry in the 1920 Baltimore Sun, but is it unclear if he found either of them: Lundborg did return to Europe in November 1920 and set up a studio in Paris together with fellow Girl’s Club artist and bookbinder Belle Mc Murty in November 1920.

Artist Studios and Models

Ateliers

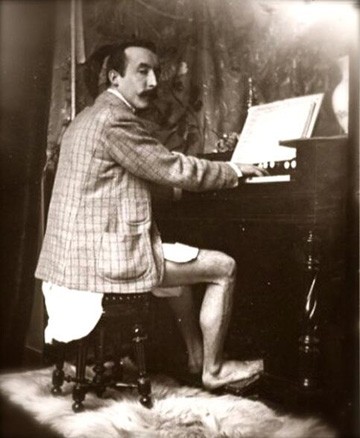

An array of painters, sculptors, and writers lived or had ateliers in Montparnasse: Paul Cézanne (5 rue de Chevreuse), Paul Gauguin (8 rue de la Grande Chaumière, 1893 – 1894), Alphonse Mucha (13 rue de la Grande Chaumière, circa 1887 – 1893, then 8 rue de la Grande Chaumière until 1896), John Singer Sargent (73 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs), Gertrude Stein (27 rue de Fleurus), August Strindberg (12 rue de la Grande Chaumière). Gauguin and Mucha once shared a studio at 8 rue de la Grande Chaumière (1893-1895) where:

Mucha rigged the studio so that when the door opened beautiful music played. An interviewer in 1900 called the studio, 'simply marvelous.' It was full of exotic objects and bohemian writers, artists, and musicians who came to work and play. An infamous photograph of Gauguin playing the Harmonium with no trousers on, captures the playful and free-spirited mood of their studio.

According to the Calepins du cadastre (AD75, D1P4), more than twenty artists’ studios were located on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs between 1876 and 1900. If one considers just the studios with large glass windows, there was: no. 73 (Laurens); no. 75 (Bouguereau;) no. 86 (four studios, including Whistler's). Numbers 105, 111, 115, 117, 118 and 119 on the street also housed artists.

Like the rue de la Grande Chaumière, rue Campagne-Première was filled with artist studios and residences: Whistler (1858), the animal sculptor Pompon, designer Naudin, photographer, Atget, and painters Modigliani, Foujita, Aragon, and Triolet. In the 1920s, the Hotel Istria (29 rue Campagne-Première) welcomed such painters as Picabia, Duchamp, and Kisling, the American photographer Man Ray, legendary model Kiki, composer Satie, and poets Rilke, Tzara, and Maïakovski.

The Models' Market

One of the characteristic sights of the neighborhood was the Marché aux modèles, held every Monday at the Vavin crossroads, on the corner of the rue de la Grande Chaumière. Here, a motley crew of mainly Italian men, women, and children showcased themselves, hoping to be selected by an artist to pose (Fuss-Amoré 208). According to Crombie (1998), "The supply of candidates offering themselves for public scrutiny and hire was in fact so plentiful as to line both sidewalks, thronging all the doorways" (47). The sculptor Janet Scudder recalled how easy it was to find a model in Montparnasse in the late 1890s:

All I had to do, when I wanted a model, was to sit at the window and look over those who came by the dozens. They were in great part Italian, though there was practically every nation under the sun represented. I have always been glad that I got to know some of them so well, for many of them contradicted all the absurd ideas that the public in general have about models being fantastic creatures without any morals or education (Modeling My Life 168).

Scudder even described the crowds of children who encircled her when walked toward the Académie where she was studying:

I used to stop often in the street before Collarossi's [sic] Academy and found myself surrounded by fifty or more little children, ranging from one year up, who immediately set up a howl to be employed as models. They had been trained from the moment they could stand on their feet for a profession that helped out the family fortunes. I often gave them pennies and looked at them longingly; in spite of their poverty and their fantastic rags, they had all the gaiety and fun and joy of living that I was growing more and more keen about reproducing. These little tots knew they appealed to me and when they found out where I lived came in hordes to my door and had great fun with the bell [...] (Modeling My Life 170).

During her brief stay on rue de la Grande Chaumière in 1910, the young American sculptress Malvina Hoffman was also greatly struck by the long lines of models “of all colours and nationalities” (Crombie 47).

Grace Hill Turnbull, resident at the Girls' Art Club, recalled an Italian model who posed for her at the Club in February 1914:

I am very happy in my studio here: and Italian models are easily obtainable. The model I have at present has three children to support and a drunken husband [...]. The infant she brings to pose, however, is as unburdened with care as any other young animal: when its mother calls it and says "Ne veux-tu pas travailler maintenant?" it shakes its head decisively and say "Pas." In other words it won't. It prefers to prowl into every nook and corner of the studio, investigate every roll of canvas, pull every string, upset every flower pot, open every door, tear every paper [...] and, finally, after manifesting every form of activity possible to a being of fourteen months, sinks panting to rest on its mother's breast [...] a dirty little bundle of still life [...] (38-39).

When the holiday season arrived each December and January, American artists made sure to share the festivities with their models. The children, in particular, were especially feted by members of St. Luke's Chapel, the American Woman’s Art Association, and the American Art Association of Paris. One such celebration at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière was recounted in the Holy Trinity Parish Kalendar (1909):

As part of St. Luke’s celebrations was the annual festival to the little children models. About 150 children were assembled in the large studio of the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, kindly given to the festival by the management. As many as 150 more gathered to help and see the children made happy. Each child received a large bun, a package of cande, an orange, and a gift – toys, dolls, and useful knitted articles prepared by the Sewing Society at Holy Trinity Lodge. The expense was largely contributed by students and artists (cited in Allen 473).

In January 1912, The Pall Mall Magazine reported on the degree to which artists were invested in the welfare of the models:

The artists themselves look after the models who pose for them, and help with the best of good will in organising Christmas-trees for the strange mixture of nationalities which makes a little world in itself, and earns its daily bread by being sketched and painted in every possible and impossible pose and costume. Whole families of Italians live this way, and sometimes hear of the profession having been followed for three and four generations, until it has grown into a family heritage. To them, a New Year's fete is a material benefit, and they go away from it loaded with good cheer and a few useful presents to help them through the winter (79).

Much to the relief of the shop owners whose windows and stalls were hidden by this horde of models, World War I brought an end to the market; the Italians were either sent back home or shipped off to fight at the front.

According to Charpy, another such models' market was held on Place Pigalle (50).

Consult the sources for the neighborhood of the Girls' Art Club