Angela Gregory, 1903 – 1990

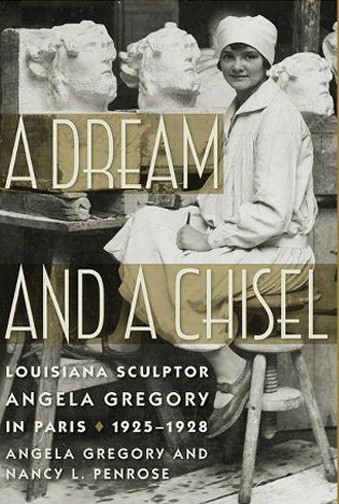

"No sculptor in France today can do a portrait any better," declared renowned sculptor Antoine Bourdelle of Angela Gregory when she was only 25 years old (A Dream and a Chisel 167).

Angela Gregory was born into an artistic and academic family in New Orleans in 1903. Her father, William B. Gregory, taught engineering at Tulane University, while her mother, Selina Brès Gregory, was a painter and potter who taught art classes at Newcomb College of Art. France, its language culture were all a part of Gregory's heritage: her father had lived in Tours as an army officer during WWI, and her mother French born.

Often described as the doyenne of Louisiana sculpture, Gregory began her first art lessons at the Katherine Brès School, where her mother occasionally taught. At the age of 14, Angela enrolled in summer classes in clay modelling and life drawing at Newcomb.

In 1921, Gregory began her formal studies at Newcomb, where noted artist Mary W. Butler became her mentor. She also studied clay modeling and was introduced to the work of French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle through her teacher Ellsworth Woodward. Gregory graduated in 1925 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in design and received a scholarship from the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts (now the Parsons School) to study illustrative advertising at its Paris branch. She saw the nine-month scholarship as her ticket to Paris: "I knew in my own mind that I was going over with one goal: to somehow study stone-cutting with Bourdelle. I certainly didn’t think of it as an opportunity to get away from my parents and go wild" (38).

Gregory was 22 years old when she sailed for France in 1925 with a group of art students from Newcomb. She was met in Paris by family friends who found hotel accommodations for her on the Right Bank, where the Parsons school was located. Although she quickly discovered that Parsons was not the right institution for her, she nevertheless continued her studies and participated in their sponsored excursions through France and Italy. While at Parsons, Gregory immersed herself as much as possible into French life and language by visiting family acquaintances in different parts of the country. Even in Paris, she shied away from the typical American hot spots:

The experiences I had in Paris in those years stand in marked contrast to those of so many other Americans. The expatriates whose names still have a magical ring today – Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Stein – spent most of their time with other Americans. They and few American students rarely got to see French family life from the inside. My style of living was very different from those legends of 1920s Paris, although I can say we frequented the same cafés! (59).

After living on the Right Bank for some time, she then moved to the Latin Quarter:

All the artists lived on the Left Bank – there were a lot of painters up in Montmartre, but the sculptors and a great many other artists were in the Montparnasse neighborhood. Most of the other students at the Grande Chaumière and the people in the studio lived in Montparnasse as well. They would never have considered living on the Right Bank and, in fact, would probably have ostracized me if they had known I had been living there. The Right Bank was for tourists and the nouveaux riches [newly rich] (105).

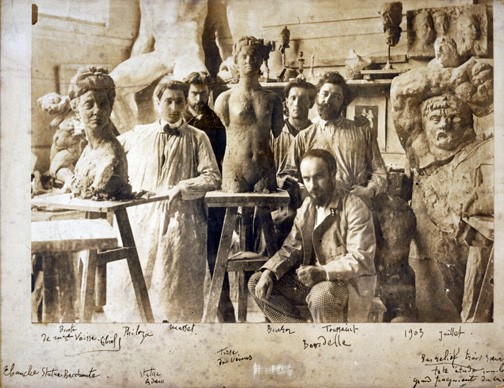

Fiercely convinced she had to work with Bourdelle and urged on by friends, Gregory finally knocked at the door of his studio. Serendipity was on her side and she managed to meet his wife, herself a stone-cutter, who arranged a meeting with her husband. When Bourdelle discovered Gregory's talent and tenacity, he gave her the keys to his private studio. For two years (1926 – 1928), she worked under his tutelage, both in his studio and at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Her memoirs, A Dream and a Chisel, testify to Gregory's unflinching admiration for the one she called "Le Maître." Over time, Bourdelle grew from mentor to friend. By working in his studio, she was introduced to his vast network of family and professional relations. She worked with stone-cutter Otto-Charles Bänninger and artist Novitza "Fanny" Moscovici Fainsilber, and met the thinker Jiddu Krishnamurti, the architect Auguste Perret, French art critic Louis Gillet, and the American art critic Walter Agard, whose article about Bourdelle had inspired her French sojourn when she was still at Newcomb.

I was the only American in Bourdelle’s studio where the atmosphere was almost as international as the Grande Chaumière. He had assistants and helpers of many different nationalities, and the mixture of accents that filled the studios was charming but terribly confusing at times! I heard French accented with Swiss German, Rumanian, Greek, and, of course, Bourdelle’s own inimitable accent of the Midi (75).

[...] I loved the unexpected quality of never knowing who was knocking at the door. Just learning to cut stone and being with Bourdelle would have been enough, yet here I was seeing and meeting people I would never have met any other way. I felt as if Paris were coming to me (111).

Bourdelle also opened doors for her to exhibition spaces like the Salon des Tuileries:

[...] exhibiting at the Salon des Tuileries was tremendously important to my career. It was my artistic debut and it gave me real credibility as an artist when I returned home to New Orleans. I could say that due to Bourdelle’s invitation I had exhibited in Paris, the very center of the art world (Gregory 167).

Many an art student envied her special relation to the charismatic Bourdelle, who was known to be wary of American art students because their time in Paris was usually short-lived.

Throughout her stay in Paris, Gregory suffered terribly from what she thought were colds and fatigue, only to learn much later that she was allergic to clay, plaster, and stone dust (Gregory 102). Worried about her daughter's health, Gregory's mother came to visit her in July 1927. Unfortunately, a few days after her arrival, she broke her leg in an accident and convalesced at the American hospital in Neuilly. Before her mother was discharged, Gregory needed to find accessible ground floor accommodations and, at the urging of a relative, went to the American University Women's Club:

Yesterday - after lunch at Uncle Ray’s - on his suggestion Edna went with me to look at the studio room at the University Club - 4, rue de Chevareuse [sic] - (between Blvd Montparnasse & rue Notre Dame des Champs) - for I was afraid that it being on the ground floor would cause it to be too damp - However upon finding it had a cellar below & was one step from the ground - it seemed eligible. It is rented for 1000 frs. ($40.00) per month – & there is a Salon, called the ‘International Salon’ – It has sky-lites all on one side with curtains - so that it has the appearance of a real studio. Heating a la chauffage centrale [central heating] - There will be cots which appear as lounges in the day time – in fact the whole appearance will be a studio-apartment rather than a bedroom. It looks out on a charming garden – & the courtyard is attractive (140).

Angela talks about how comfortable and engaging she and her mother found life at the Club. Miss Leet, the Club's director, is described as a charming, talented, and skillful manager who became her dear friend. Gregory also praises the Club's food and the good heat it provides in colder weather, an amenity not to be taken for granted in damp, chilly Paris.

The Hall served as home and meeting place for American students. I had always avoided it for that very reason, because of my desire to meet as many Europeans as possible. But by the time I moved there with my mother I had already established my French ‘"oots," had my French friends, and felt free to meet and enjoy the other Americans who were living in or just visiting Reid Hall. Not only was I able to secure a ground floor apartment, but meals could be obtained in the dining room as one wished and there were evening activities in the Salon. Add to these benefits convenience, for the charming courtyard was just across the street from the Grande Chaumière and Bourdelle’s studio was a relatively short walk away (141).

One of the highlights at the Club was its social life. Gregory quotes a letter her mother wrote to her father in October 1927, describing how happy they were in their new context:

We are more thankful that we came here. It is simply lovely. Vespers in St. Luke’s "in chapel" just ten steps from our door at 5:30 on Sunday. A lovely concert and coffee and dancing in the assembly hall, making a very lovely opportunity for one to hear good music for nothing and enough social life to keep the students from getting restless or homesick. Miss Leet, the manager, is a lovely young woman from New York (143).

She notes that the concerts often featured young, up-and-coming musicians in need of an audience, and that the programs sometimes included speakers like Tolstoy's daughter (146). In one of these Salons, which Gregory qualified as one of the best parts of living at the Club, she met Joseph Campbell, a Columbia University graduate studying philosophy at the Sorbonne. She connected him with Krishnamurti, who was then posing for Bourdelle.

The warmth, food, and sociability at the Club were always accompanied by "intellectual nourishment at Bourdelle’s studio" (155). The Club even provided Gregory with further opportunities to grow and display her artistic talents:

As 1928 began I was working on the portrait bust of a beautiful young American woman, Adelaide McLaughlin, who was also staying at Reid Hall. Seeing her across the dining room as we sat eating one day, my mother had said, "f you want a beautiful model, there she is." So thanks to my mother’s artistic eye and knack for meeting people, we introduced ourselves, got to know her, and she consented to pose for me in Bourdelle’s studio (149).

Bourdelle also cast her portrait, after having been introduced to Adelaide by Gregory, who describes the bust as "more romantic" than hers. In this same period, Gregory also worked on a portrait bust of Clare Wadleigh, a young painter who was the daughter of Dr. Henry Wadleigh, the Episcopal minister overseeing St. Luke's Chapel.

Gregory appreciated her mother's presence, support, and camaraderie; they traveled to the south of France, visiting Nice, Marseille, and Avignon, places that inspired paintings and sketches. Among the works they brought back to Paris were 12 oils Gregory painted in Les Baux, Cannes, Carcassonne, Villefranche, and Montauban, all of which Bourdelle admired, saying she was a gifted painter (Gregory 154).

Her years in Paris culminated in two exhibitions:

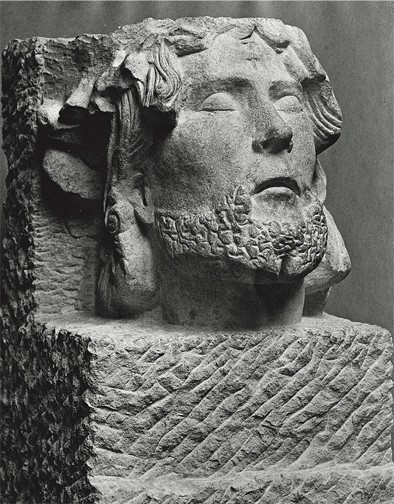

- The first, at the Salon des Tuileries, which opened on May 4, 1928 at the Palais de Bois at Porte-Maillot, she showed her bust of Adelaide McLaughlin and her "Beauvais Head of Christ" in stone. Other notable exhibitors included Bourdelle, Fanny Bunand-Sevastos, Elizabeth Chase (another American student of Bourdelle’s at La Grande Chaumière), Bänninger, Giacometti, Mateo Hernández, André Lhote, Piet Mondrian, Fainsilber, Henri Matisse, François Pompon, Germaine Richier, and Maurice Utrillo (Gregory 167-168).

- The second, at the University Women's Club on May 12, just before her return to the United States. She showed the "essence of [her] three years of work and travel in Europe": nine sculptures, fifteen oil paintings, and nineteen watercolors (169). The Club exhibit was favorably reviewed by Georges Bal for The New York Herald (European edition), who described Gregory as handling "with equal success the sculptor’s ébauchoir [chisel] and the painter’s brush [...] I do not doubt Miss Gregory will rapidly succeed in ripening her talent, which is still rather youthful, but is full of promise" (May 13, 1928). Gregory described with excitement all the French and American friends she invited to this show, including U.S. Ambassador to France Myron T. Herrick and, of course, Bourdelle and his wife (169).

After learning she had not received the Guggenheim fellowship for which Bourdelle had written her a letter of recommendation, Gregory decided to return to the U.S.:

My reaction was fairly philosophical, however, partly because at this point in time I was feeling ready to go home. I had been away long enough and a Guggenheim would have meant at least another year in Paris. 'So now my future is definitely settled and a calmness has entered my soul,' I wrote to my father on March 31. 'For as much as I longed to go home & be with you and all the family—the thot [sic] of a possibility of staying on in Paris hung over me a tiny bit—and now at last every trace of shadow is removed' (Gregory 159).

She sailed with her mother on the S.S. Grasse on May 27, 1928, reassured by Bourdelle's warmth:

[He] said to me not long ago, that I had work[ed] well over here & was quite prepared to go home to produce—And he was dear enuf to tell me to send him photos of whatever I do—so he could write me his criticism and kept in touch with what I do (160).

They returned to their family home in New Orleans, where Gregory and her father built a studio for her at the back of their house; it became her workplace and home until she died.

Bourdelle died on October 1, 1929, shortly after Gregory's departure.

His passing devastated me; for not only had I lost a dear and wonderful friend, but also my mentor and my maître in the truest sense of the word. I could never turn back to him again, never learn any more from him. He was gone and I was truly on my own (171).

Gregory maintained lifelong friendships with Bourdelle's widow, daughter, and son-in-law, with whom she corresponded and whom she saw whenever she visited Paris.

Upon returning to the U.S., she executed several commissions: a pelican for the New Orleans Criminal Courts Building (1929 –1930); several historical bas-reliefs for the new Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge (1931 – 1932); and the head of Aesculapius on the entrance to Tulane's new medical school building in downtown New Orleans (1930). She continued sculpting alone or with a team throughout her life, leaving behind a rich legacy of monuments, bas-reliefs, and portrait busts.

Other notable achievements include being the first woman to earn an M.A. from Tulane University's School of Architecture (1940); serving as the state supervisor for the Louisiana Art Project of the Federal Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression; and working as assistant architectural engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers in New Orleans during WWII. Gregory was professor and sculptor-in-residence at St. Mary's Dominican College (New Orleans) from 1962 to 1976, when she was named professor emerita.

From her studies in the Bourdelle atelier to her stay at the University Women's Club, Gregory's time in France remained the highlight of a rich, full life that brought her back to Paris on several visits. Around 1953, she and her mother stayed in Paris for two years for the casting of the life-size Bienville Monument, featuring Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the founder and first governor of New Orleans; a priest; and a native American (1950 – 1955). Her mother died near Paris in 1953.

Nancy L. Penrose provides the most comprehensive biography of Gregory, whom she began interviewing in 1983 and whose memoirs she edited and published in 2019. During this period, Penrose and Gregory developed a strong friendship by talking and poring over Gregory's letters and diaries, which are preserved today in the Louisiana Research Collection at Tulane University. They finished the manuscript in 1990, just weeks before Gregory died on February 13.

In the Prologue to A Dream and a Chisel, Penrose invites readers into Gregory's studio:

I loved the atmosphere there: the abundant light that fed through two-story windows, the exposed walls of barge board, the workbench lined with tools. We worked surrounded by her sculptures of bronze, stone, and plaster displayed on shelves and sitting on pedestals, each piece embodying memory and history. That atmosphere held the riches of her artistic spirit, the mysteries of concept coming into being, of vision finding expression. It was as if her studio and sculptures were participants in the writing of the book (13).

Sources

- Angela Gregory- Life and Art, website, 2021.

- Angela Gregory: A Sculptor's Life, Exhibition sponsored by the Southeastern Architectural Archive Newcomb College Dean's Residence (New Orleans: Newcomb College, 1981).

- Bal, Gregory, "....

- Gregory, Angela and Nancy L. Penrose. A Dream and a Chisel: Louisiana Sculptor Angela Gregory in Paris, 1925-1928. Univ of South Carolina Press, 2019.

- Ormond, Suzanne and Mary E. Irvine. Louisiana's Art Nouveau: The Crafts of the Newcomb Style. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing, 1976.

- Rubinstein, Charlotte Streifer. American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1990, pp. 293-296.

- "Angela Gregory- Sculptor, Educator, and Trailblazer." St. Mary's Dominican High School, October 17, 2018.