Wartime Refuge, 1939 – 1947

Gertrude Homans Cooper had only enjoyed a brief tenure as Director of Reid Hall when World War II engulfed Europe in brutal conflict. With France mobilizing immediately following Hitler's Sept. 1, 1939 invasion of Poland, Reid Hall's staff scrambled to secure the buildings and evacuate the residents as swiftly as possible. The loyal members of the Association des Françaises Diplomées des Universités remained on-site until January 1940 but had to finally leave the premises as there was no heat nor the means to stockpile coal.

Reid Hall was no stranger to wartime adjustment, and the question of what should be done with the facility weighed heavily on many people's minds. An empty building could have potentially serious maintenance issues but even worse would be likely requisitioned by the Nazis.

Wartime Adjustments

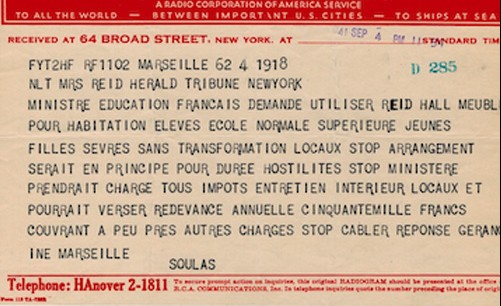

Radiogram sent by Victor Soulas, September 4, 1941. RH Archives

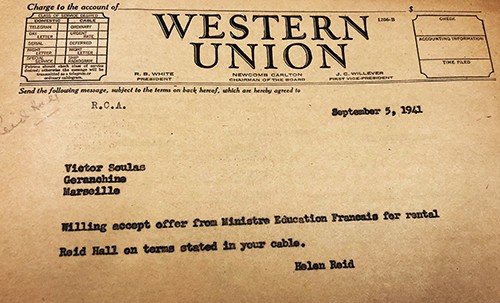

Telegram from Helen Rogers Reid to Victor Soulas, RH Archives

Virginia C. Gildersleeve found herself in Paris when war became inevitable. She chronicled the tension at Reid Hall and the difficult decisions its leaders were forced to make in 1939:

On a newspaper bulletin board I read accounts of alleged atrocities perpetrated by the Poles on German women. In Paris the following morning the news of the Russo-German Pact told us that war was certain. Dean Margaret Morriss of Pembroke College, President of the American Association of University Women, had traveled down from Sweden with me. We went to stay at Reid Hall, but in the afternoon we wandered out across the river and sat in the Tuileries Gardens watching the flowers and the fountains playing and the children at their games. We knew that it would be a long time before we saw again this familiar scene. That night, in the Director's Salon of Reid Hall, with the light dimmed very low, Mrs. Cooper, then director, her young secretary Barbara Howard, Dean Morriss and I, and later two French friends of ours, M. and Mme. Puech, discussed how best to evacuate the residents and to secure some protection for the buildings (Many a Good Crusade 162-3).

After Reid Hall was closed in the first week of September 1939 (Newcomb, January 26, 1940), Gertrude Homans Cooper placed the facility in the custody of Reid Hall’s British receptionist, Harold Garnham, and his wife. Victor P. Soulas, of the firm Harper, Szlapka & Harper, which oversaw Reid Hall's legal affairs, was given power of attorney for the financial accounts, reporting directly to Helen Rogers Reid at the Herald Tribune (Unknown, November 2, 1939; Brown, December 21, 1939). Cooper returned to the U.S. in mid-October 1939; her secretary Miss Howard had already left in September (Newcomb, January 26, 1940). Reid Hall stood empty while several proposals on how to maintain the property during the war were considered.

Marie Monod and Marie-Louise Puech, heads of the AFDU, made repeated appeals to Gildersleeve to use the site as a dormitory and workspace for exiled university women from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Spain (Monod, February 22, 1940; Puech, March 19, 1940). Initially, Gildersleeve and members of the Reid Hall Board felt this might be a worthwhile initiative:

It seemed to us that in this dark hour, when so many of our foreign colleagues were suffering and dying, we could not possibly refuse this request from the French Association for the use of Reid Hall to house university women refugees. We have just about enough money in our Paris accounts to cover our contributions for the experimental year. As for the distant future, no one knows what will happen to the world. Possibly Reid Hall will be blown to bits next week. We shall have to deal with the emergencies as best we can as they come along. Our refusal to aid the French in caring for their foreign refugees would, we felt, be a serious blow to their morale at the moment, and would make them feel that all our expressions of American sympathy are insincere (Gildersleeve, March 13, 1940).

Unfortunately, the project never materialized, as the AFDU leadership realized it might be too complicated and potentially dangerous. However, a group of Belgian families took shelter at Reid Hall for a week (Puech, June 4, 1940) and a number of women refugees from Poland and Czechoslovakia stayed several nights (Puech, July 15, 1940).

In the fall of 1940, the AFDU moved its headquarters to the Maison des étudiantes on boulevard Raspail, where they maintained contact throughout the war with university women refugees sheltering in different parts of France (Femmes Diplômés, 1965, 7; Puech, February 1941, November 17, 1941 and December 4, 1944). Gildersleeve and Unitarian religious groups contributed funds to support their efforts (Puech, November 17, 1941).

Another proposal came by way of the Red Cross, who approached Helen Rogers Reid, wanting to use 4 rue de Chevreuse as a residence for soldiers on leave (Minaham, February 8, 1940). Puech, Soulas, and others vehemently opposed the idea, claiming it was impractical and would generate too many logistical issues. There were overt racist assertions about foreign soldiers in their objections:

[...] having come from afar, such as Negroes, Indochinese and Moroccans, [...] one shudders to think what might become of Reid Hall when preyed upon by these poor people, generally dirty and arriving full of vermin! [...] we would be sorry if all this resulted in an occupation by negroes and chinks giving some idle, old women the occasion to get busy (translated from French, Puech, Feb. 7, 1940).

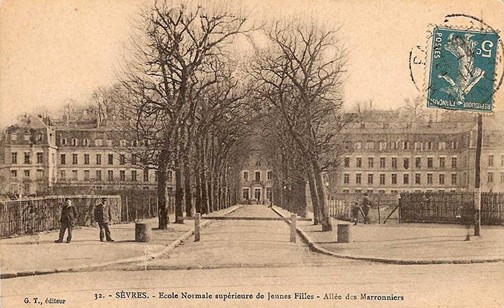

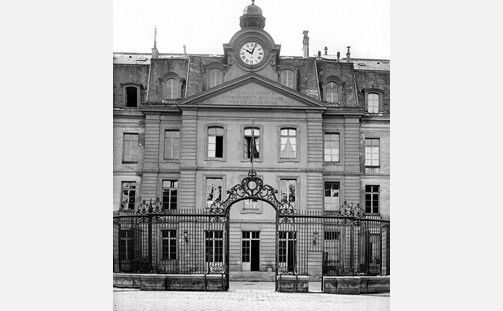

A solution for the vacant property was finally found in 1941 via Eugénie Cotton, Director of the École normale supérieure des Jeunes Filles de Sèvres. As a loyal member of the AFDU and a regular at Reid Hall, her appeal to Gildersleeve that the school could use 4 rue de Chevreuse as their base during the war was accepted. Their own campus had been occupied and ransacked by the Germans, and she had already secured some housing at the Maison des étudiantes at 214 bd. Raspail. The additional space provided by Reid Hall would house the remaining students and administrators:

On June 9 and 10, 1940, Eugénie Cotton, director of the E.N.S.J.F. since 1936, sent the students of the graduating classes of 1937 – 1939 back to their homes, which they did in the general debacle, at the cost of enormous difficulties. The old house in Sèvres was abandoned. The Germans occupied it three times, from June 14 to 18, 1940, from August 14, 1940 to April 13, 1941, and May 5, 1944 until the Liberation in August. The occupants turned the buildings into military barracks, ransacked the rooms, stole the furniture, and looted the supplies. Only the library and the laboratories were were temporarily spared (translated from the French (Cavigneaux 28).

For these lucky French students, living in the Latin Quarter would be a remarkable opportunity to pursue their education. They could walk to the Sorbonne and other institutions, and classes were also held at Reid Hall.

After much discussion and lengthy negotiations with the French Ministry of Education, Reid Hall was leased to the École normale supérieure des jeunes filles de Sèvres. The École agreed to pay the property taxes, the caretaker's salary, and fund necessary repairs (to the tune of 150K francs, outside of the roof and foundations). Reid Hall's Board of Directors approved the proposal because it would ensure the continued maintenance of the buildings, and prevent the Germans from requisitioning the property for their own use (Puech, September 15, 1941).

The agreement to move into Reid Hall was finalized by Eugénie Cotton and the "Sévriennes" were granted Reid Hall as their headquarters until the liberation.

On September 4, 1941, Mr. Soulas dispatched a radiogram to Helen Rogers Reid at the Herald Tribune in New York confirming the Sévriennes’ impending tenancy of the property.

The Sévriennes

The school’s administration and students in the literary track of the École resided at rue de Chevreuse while the mathematics, philosophy, and history track students were housed at the Maison des étudiantes.

Eugénie Cotton was abruptly dismissed from her position on October 13, 1941 by the Vichy government who condemned her left-wing politics (Brohand-Mercier 29). She was replaced by Edmé Hatinguais, whose profile did not match those of the École’s previous directors, as she did not have experience in higher education. She owed her appointment to Jerome Carcopino, Secretary of State for National Education and Youth, who had known her in Algiers, where she was the first female censor and then director of a women’s high school, which she had built. Upon returning to France, she directed the Lycée Racine until war broke out. The Sévriennes resented her appointment:

[...] we had never heard of [her] and [she] did not seem to us to present the desirable profile for the director of a school of higher education. Until then, the principals (except for the first one, of course) were former Sévriennes and some had completed important [academic] work. Physically, too, it was different: Mme Hatinguais was coquettish and tried to charm us; she had brought with her two high school supervisors: Mlle Delcoustal on boulevard Raspail and Mlle Barat on rue de Chevreuse [...] (translated from French, Juliette Cossoul-Crenn 23).

They were also concerned by the fact that Mme. Hatinguais, like all civil servants appointed by the Vichy government, had sworn an oath to Marechal Pétain in 1941:

This oath required her to adhere to the new legislation that was either treacherous or persecutory (law of October 3, 1940, concerning the status of the Jews; law of June 21, 1941, regulating the conditions of admission of Jewish students to institutions of higher education) (translated from French, Cavigneaux 31).

Hatinguais did not hide her political allegiance and she even organized workshops outside of Paris at which the Sévriennes were forced to salute the Vichy flag and sing songs praising Maréchal Pétain and his government. Hatinguais, who lived in an apartment at Reid Hall, welcomed:

[...] Germans in uniforms... In the School, we saw advertisements for German propaganda sessions... When Anti-German tracts were found in a hallway, Mrs. Hatinguais had them taken to the nearby police station... She thought and said that Jewish students should abandon their studies since they would never become professors... (translated from French, Brohand-Mercier 29).

When Denise Brohand-Mercier, a student living at the Raspail residence, was arrested by the Gestapo for her work with the resistance group, the Vélites-Thermopyle, Hatinguais fully cooperated. Brohand-Mercier was interned at Fresnes for 33 days, during which Hatinguais interrogated several of her friends and had her room carefully searched. As Hatinguais had not been able to produce incriminating evidence (a friend at the École had hidden all compromising documents), Brohand-Mercier was released, but did not return to the school.

In the words of another Sévrienne, Hatinguais ruled with an iron fist and scrupulously followed regulations imposed by the Vichy government:

[...] she created an atmosphere of authority and control in the school. The rooms were strictly supervised – we had no key – Saturday evening and Sunday outings were granted only in groups of four and on written request, the first sentence of which remains in my memory: "We present our respects to the Director, and...," followed by the list of the four obligatory names, then the precise place and activities to which we were going (translated from French, Rouffy-Boué 43-44).

After the liberation, Hatinguais was removed from her post by Henri Wallon, then Minister of National Education, and was replaced by the philosopher Lucy Prenant, who had fought in the resistance movement. When a new Minister was named, Hatinguais’ case was examined by an investigative committee, and she was reinstated by a January 24, 1945 order. The Director of Higher Education, in charge of executing the order, specified on February 9, 1945 that he had decided "not to retain any of the grievances articulated against Mrs. Hatinguais and not to impose any sanction against her" (translated from French, Cavigneaux 32). Hatinguais went on to direct the Centre international d'études pédagogiques (CIEP), created in 1945 by Gustave Monod – a public institution under the direct supervision of the Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research. She stayed as director until 1966 and died in a car accident in 1972.

The Sévriennes at rue de Chevreuse were more fortunate than those at boulevard Raspail: Hatinguais had decreed that given the shortage of coal, only Reid Hall would be heated (Paulette Mathieu-Lévy-Bruhl, et.al. 40). In addition, Reid Hall had a dining room (open to the students of both residences), a library, as well as classrooms. In contrast, the Raspail facility had little more to offer than bedrooms:

[...] often without heat, without hot water, without baths or showers [students went to the baths on the rue Delambre]; the only source of warmth in these harsh winters was the expensive hot water bottle that one was allowed to prepare from the water of one's own kettle. On each floor there was a room open from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m., equipped with a single-burner gas stove, so that the girls queued up, and one could hear "it's boiling" in the hallway (translated from French, Mathieu-Lévy-Bruhl, et.al. 40).

One of the “lucky” Sévriènnes recalled her stay at Reid Hall:

The old house of the rue de Chevreuse was a haven for us. We immediately felt at home; quickly, we were happy to live there together, in a closed space where we felt protected from the aggressive presence of the Germans [...] Agreeably open onto the garden through its large windows, the dining room rustled with animated conversations [...] At 7:30 p.m., our concierge and zealous guardian, the fearsome Joseph, shut the heavy door giving onto the outside world on the rue de Chevreuse [...] our nights were sometimes interrupted by the howl of sirens. Aerial alerts! We had to leave our rooms running to the basement of a neighboring convent that served as shelter [...] (translated from French, Patois-Pinaud 2).

Another Sévrienne also described the benefits of living at 4 rue de Chevreuse:

It was October 1945. The war had just ended: it had been hard. In our class there were several of us whose souls were clouded with tears [...]. Sèvres was then located on rue de Chevreuse, a stone's throw from the Luxembourg, in a lovely house with a doll's garden and staircases that were a little choppy but full of a warm mystery. My very first satisfactions were of a very humble order: I was delighted... specially to have, for the first time in my life, a bed all to myself in a room all to myself. [...] I savored my new solitude all the more because on the landing where my room was located, I discovered the same evening a cupboard that held the complete collection, since 1929, of the journal Les Annales. [...] Life at Sèvres was still quite similar to convent life. We were certainly allowed to go out freely during the day, if only to follow our courses at the Sorbonne: but of course, we had to return [to the school] for meals. However, in 1945, this was not a constraint: even if out of fourteen weekly meals, we easily counted thirteen that were composed of a dish that the force of habit made us call "pasta," it was worth it. It would be an exaggeration to say that we were hungry: things were not as they had been in 1943 – 1944. But we ate very badly [...] In the evening, the doors of the school were definitely closed at 10 p.m., except on Saturdays, when we had a midnight pass. In fact, it was rare that any of us went out after dinner. By 8:00 p.m., we had to return to our respective rooms where a supervisor would come by to kindly wish us good night or good work. In fact, we worked a lot. [...] No boy, of course – and not even the inevitable brothers and cousins – was allowed beyond the parlor. Only priests [dressed] in their vestments could, paradoxically in this world of lay consecration, go upstairs. [...] At that time, there was a dense, restrained, and open intellectual and spiritual life at the school (translated from French, Kriegel).

Another Sévrienne described the trials and tribulations of war but also the joys of learning to live in a community:

During the war, we were hungry. And every meal counted. But, above all, even if our plates, despite of the efforts of the steward, were poorly supplied, we felt, in those moments when, coming out of our books we found ourselves, literati and scientists (who were living at 214 bd. Raspail), intermingled around long tables of ten to twelve place settings, a satisfaction of being together, a feeling of belonging which, through the years, the dispersals, the difference of destinies and careers, still binds us today. [...] Between us, intellectual freedom and tolerance were total. [...] This patience was opposed, in secret, by courageous initiatives. Outside of any network, one of our colleagues, in liaison with a friend, was in charge of placing Jewish children in safety in the countryside, where she accompanied them, a dangerous undertaking among all others. Others, under the calm façade of daily life, belonged to a Resistance network. They spread leaflets in the streets, met other resistance fighters, accepting, like thousands of anonymous actors of the future liberation, the serious risks that their commitment made them run. One scientist did not escape arrest and was imprisoned by the Gestapo (translated from French, Patois-Pinaud 3).

Camaraderie and companionship were the optimal remedies for the miseries and restrictions generated by Hatinguais and the German occupation:

Despite the rigors of war and the lack of entertainment, life inside the school always seemed pleasant and even joyful. In our class, both literary and scientific, there was a very good understanding. We met from time to time in a room to chat, sing, make music or enjoy a special treat together. [...] On our days off, we went on long walks around Paris, among fellow Normaliens and Sévriennes, or with the Auberges de Jeunesse. Sometimes we camped. Fields and forests are and, far enough from the cities, we felt tranquil, far also from the Germans. We could almost forget them (translated from French, Rouffy-Boué 43).

Even after the war ended in 1945, the Sévriennes remained at Reid Hall, leaving only in 1947 when new dorm facilities had been procured. Many students, like Valéria Tasca, regretted their departure, experiencing a sense of loss and a kind of homesickness for the place in which they had found solace, especially when Lucy Prenant was at the helm:

At the beginning of the 1947 school year, we left "home." For us, as for the previous generations, the term had a concrete meaning, which it would no longer have, or much less so, when the school was transferred to boulevard Jourdan. The new premises were brighter and more functional, we kept the same study facilities, the classes in small groups, the library, and the free access to books that we took to our rooms. But we had lost some of our privileges: walking to the Sorbonne through the Luxembourg, having classes in small familiar rooms, like living rooms, and even staying in rooms with slightly outdated furniture. In the early years, two of us could occupy an artist's studio, on the north side, as it should be, with one side entirely glazed, overlooking the big wall all covered with ivy. I forgot my lack of taste for dilapidated chests of drawers with grey marble tops, and for me, it has remained the image of luxury. [...] to speak of the joy of life at Chevreuse is not an optical illusion (3).

Liberation

Scott Frederick Runkle in Germany on the road to Berlin, March 1945. "Here is Runkle, dirty and tired and not looking too sharp in his helmet, on a junket in Germany." Photo and caption courtesy of Isabelle Runkle de la Vega, 2019.

The Allied Forces entered Paris on August 19, 1944. The French capital was liberated on August 25 when the Nazis surrendered. During that week, U.S. Army Major Frederick Runkle, who had landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day, was among the first Americans in uniform to enter Paris.

Runkle had been to Reid Hall while studying at Sciences Po from 1936 to 1937 as a Dartmouth student. Amid the confusion and exhaustion of the liberation, he sought a safe haven for his regiment and immediately thought of 4 rue de Chevreuse. The following letter represents his vivid recollection of that emotional return:

[...] By the time we had sent our last report, and had drunk innumerable toasts at the Invalides, it was late in the evening and we were exhausted, having had little sleep for 48 hours. We could not leave our jeeps unattended and were too tired to mount guard over them. We had to find shelter for them so we could sleep. I immediately thought of Reid Hall, with its stout outer door and inner courtyard. It must have been about 11 p.m. when we drew up at 4, rue de Chevreuse, which seemed very silent, contrasted with the noisy celebration on the blvd. Montparnasse nearby. I knocked on the door. After some delay, an old man opened it cautiously, then ran back inside, shouting: "Les américains ! Les américains sont là !" We were still waiting outside, but the sound of people bustling inside grew, until a very large woman of middle age appeared, grabbing me in a mountainous embrace. She was, we learned, Mme. l'économe of l'École Normale de Sèvres. The doors were opened wide so we could drive our jeeps inside. Then all the young women of the school descended on us, in a state of high emotion and curiosity. I, of course, had no idea that Reid Hall had been taken over during the Occupation by the École de Sèvres. All we wanted to do was to sleep. All they wanted to do was talk. So we talked for some hours, about la France, les États-Unis, la guerre. One wanted to know if Cherbourg was badly damaged; I reassured her that it had suffered little in the fighting, but Caen and St. Lô... that was different. Les jeunes filles were excited but we became increasingly inarticulate with fatigue. Finally, we were given beds on which we fell gratefully, without even bothering to undress. We stayed at Reid Hall for several days until we were assigned regular quarters, but during that time we saw much of the young normaliennes, who were delightful. There was much picture-taking of the girls sitting in our jeeps in the courtyard, and... in those few days which were very unstructured, we would take them for rides in our jeeps. They found this particularly felicitous. No romances, sorry, but much camaraderie, until we were whisked off to our assignments, scarcely looking back, which was the way things happened in the army in wartime. La guerre, c'est laisser les choses derrière, même des moments délicieux comme celui de la "libération" de Reid Hall. It was only later that I reflected on the symbolism of those days, and that I, a former denizen of Reid Hall, had had the honor of playing a modest role of seeing it restored to its ancient freedoms ("Some recollections of Reid Hall on August 25, 1944", Reid Hall archives).

The Aftermath of WWII

Victor Soulas, who had handled Reid Hall's finances throughout the war, was arrested in 1944 by the "Free French on the charge of having collaborated with the Germans" (Brown, Nov. 1, 1944). He was temporarily released in early 1945. His powers of attorney were revoked and he was stripped of his access to Reid Hall's financial accounts. Renée Brasier at the Paris branch of the Herald Tribune was then given power of attorney for Reid Hall. She appointed a solicitor to attend the opening of Soulas' safe at the Morgan bank in Paris, where his assets were frozen. Inside the safe, along with Soulas’ personal funds, they discovered 44,000 francs belonging to Reid Hall and 112,000 francs belonging to the Paris branch of the Herald Tribune (Brasier, December 27, 1944; Minutes of the meeting of the Executive Committee of Reid Hall Inc., January 5, 1945). The fate of Victor Soulas remains unknown.

Leet and Gildersleeve had kept in regular contact throughout the war, and both were most eager to see Reid Hall open to international university women again. In April 1945, Gildersleeve wrote to U.S. Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., requesting permission to send Dorothy Leet to Paris to survey the conditions at 4 rue de Chevreuse with an eye toward reopening the Club as an educational center. Gildersleeve notes in her letter, "The break in our cultural relations with France has been, of course, very serious, and anything that can be done to pick up the threads again should certainly be undertaken as soon as may be possible."

On May 25, 1945, Marie Octave Monod (of the AFDU), who had regularly corresponded with Leet and Gildersleeve during the war, urged Leet to come to Paris and reclaim the University Women’s Club by negotiating with the École de Sèvres. By leveraging her political connections, Dorothy Leet succeeded in traveling to Paris in early September 1945, and stayed at the Hotel Bristol before returning to the U.S. on September 30. During her brief visit, she met with Monod, members of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of State, and the American Ambassador to France. She also visited Reid Hall, which she qualified as “lovely” but “barren” (Leet, September 9, 1945). There, she and Renée Brasier met with Lucy Prenant, the new director of the École de Sèvres. The Sévriennes were originally scheduled to leave the premises immediately following the armistice but Prenant negotiated a one-year extension on the lease. Since a contingent of German soldiers had occupied and ransacked their old building, the Sèvriennes had not yet found a new home.

Tensions ran high throughout 1946, as Gildersleeve, Leet, and the Reid Hall Board of Directors were keen on reclaiming the space from the Sévriennes by autumn. They did not intend to simply restart the University Women’s Club. In addition to research scholars, they wanted to attract American study-abroad programs. Much to their chagrin, the École asked for yet another through August 1947. In an April 14, 1946 letter to Leet, Monod explained that while the École had found a new property, it would not be ready for occupancy until 1947.

Leet resigned from her position as Secretary of the Foreign Policy Association in order to fully concentrate on reopening Reid Hall (letter to Bonnet, September 14, 1946). She made plans to return to Paris while Gildersleeve secured the support of Henri Bonnet, French Ambassador to the U.S. (Gildersleeve, September 23; Bonnet, October 6, 1946), and Jefferson Caffery, U.S. Ambassador to France (Gildersleeve, September 23; Caffery, October 1, 1946). Both agreed to support Leet in her mission.

After meeting with Bonnet in New York on September 24, 1946, Leet sailed back to France on September 30, intending to stay for two months (Letter to Bonnet, September 14). She stayed at the Hotel California in the eighth arrondissement, where she had access to heat and electricity (Letter to Gildersleeve, October 30, 1946). Prior to her departure, she composed a long memo outlining the various matters that needed to be addressed before Reid Hall could reopen: fundraising (for example, the creation of a national “Friends of Reid Hall”); inviting new members to the Board of Directors; upgrading the buildings, furnishings, and gardens; creating and disseminating a brochure about Reid Hall to American colleges and universities; and, finally, organizing the the space to host students (September 23, 1946):

The major problem is, of course, getting the school out of the property and Mme. Prenant has no intention of going in spite of all her agreements. I shall not leave Paris until this is entirely settled. However, we have all the support on our side with the exception of the fact that the School cannot find another property, and (confidentially) the complexion of the Min. of Nat’l Educ. is such that they have no interest in returning private property to the rightful owners. Therefore, we are working through the Min. of Foreign Affairs, which is very anxious to have us back. The Embassy, through John Wood, who is in charge of Amer. property in France asked that Mlle. Brasier (since she had signed the agreements for the new conditions of the lease) send a registered letter to Mme. Prenant, stating that we shall take over the property in July – August, 1947, as agreed, and asking for confirmation of the agreement. We are asking for 10 rooms on July 20 and the whole house on Aug. 20th. The power of att. must be kept in Mlle. B.’s hands until this is accomplished. She will give me this letter today and I shall show it to our lawyer before it is sent. A copy will then go to the Embassy with a statement from our lawyer that we have complied with the terms of the lease. The Embassy will then write to Mr. Dennary [Étienne Dennery, then director for American affairs at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs] at the Quai d’Orsay that this letter has gone to Mme. Prenant, and that the Embassy wishes that the Min. of For. Aff. to take up the matter with the Min. of Nat’l Educ., so that the agreement will be carried out as arranged (Letter to Gildersleeve, October 30, 1946).

After a short stay in the U.S., Leet returned to Paris in May 1947. Her extensive political connections ensured the departure of the Sévriennes by the end of August:

The second point is Mme. Prenant. She has no intention of giving us the property on Sept. 1st, and there are certain laws that might protect her. […] Saturday, Mme. Prenant invited me for tea. When I got there, she had Mme. Hatinguais, the former directrice of Sèvres and current occupant of the Sèvres property (and head of the Sèvres experimental school). Mme P. said that she cannot leave Reid Hall until November, and that Mme. H. had worked out a whole preparatory course at Sèvres for our students for Sept. and Oct.. Of course, I said that it was impossible, that we must have the property for Sept. 1st and then rose with the statement that I would never discuss the question with her again. She does not see why she cannot continue to make us offers! […] The Embassy feels that I must get on the property as soon as possible, which may be August 15 when Mme. P. will leave her rooms for vacation. […] It is very important to the French that we come, and I think that Mr. Joxe [then General Director of cultural relations at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs] will not permit any slip in the plans. I can assure you that I shall not! (Letter to Gildersleeve and Slade, June 10, 1947).

Leet’s resolve paid off and Reid Hall was able to reopen as an American educational center in September 1947.

The Winter 1947 issue of the Barnard College Alumnae Magazine included a brief report by Dorothy Leet on the general situation in Paris:

Electricity is cut off two days a week, because of shortages, and this of course affects lighting, cooking, heating, elevator service and many other services which depend upon electricity. In spite of all this, Paris seemed more beautiful and satisfying than ever. The city was full of art exhibits of extraordinary interest, – tapestries from the middle ages to today, a re-arrangement of the treasures of the Louvre, an exhibit of paintings from looted private collections now returned from Germany.

Leet concluded her report with a promise that Reid Hall would soon be ready for visitors: "We shall look forward to welcoming you there in the years to come so that you, as American university women, may share in renewing the cherished ties between our country and the continent" (5).

Sources

Consult the sources for Wartime Refuge.