Helen Rogers Reid, 1882 – 1970

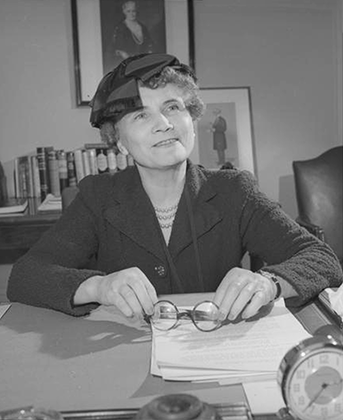

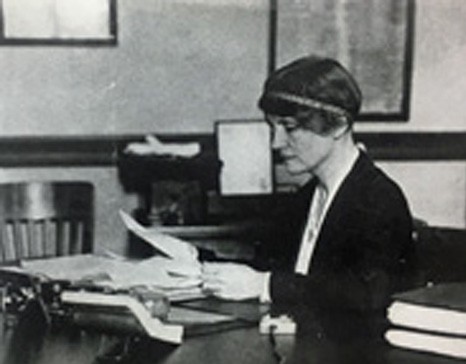

There was little in Mrs. Reid's appearance to suggest the influence she wielded, nor the force of her character. She stood only an inch over 5 feet; and she looked as fragile as a piece of expensive china. Her hair, at first brown, then gray and later white, was a fine soft fuzz that curled close to her head. Her large green eyes, however, were alert and probing. According to advertising salesmen who dealt with her, they could be quite unnerving (New York Times obituary, July 28, 1970, 1).

Born in Appleton, Wisconsin on November 23, 1882, Helen Miles Rogers was the youngest of eleven children. Her father was successful in business but the Rogers family had neither the wealth nor the connections of Helen’s future in-laws, the Reids. Helen graduated from Barnard College with a B.A. in zoology in 1903, having worked her way through school by tutoring classmates, working in the bursar’s office, and even working as an assistant dormitory housekeeper. She was an active member of the Barnard community, singing in the chorus and volunteering at the Henry Street Settlement in her spare time (Doenecke 4). Though she had planned to teach Latin, she instead went to work as the social secretary for one of New York’s grande dames, Elisabeth Mills Reid. Helen traveled with Elisabeth between the United States and the United Kingdom, where Elisabeth’s husband Whitelaw Reid held a diplomatic post.

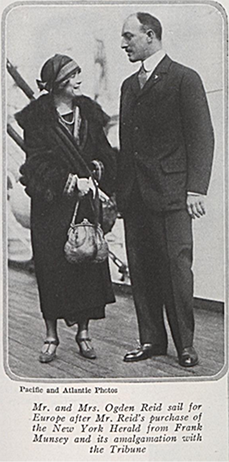

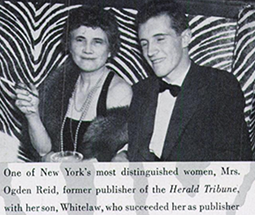

After nearly eight years of service, she left her position as social secretary in 1911 to marry Elisabeth and Whitelaw’s son, Ogden Mills Reid. Helen and Ogden were married for nearly forty years and had three children, a daughter who died of typhoid in childhood and two sons, Ogden and Whitelaw.

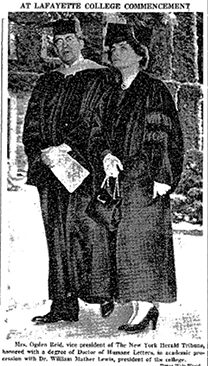

It was through her husband that Helen entered the world of journalism, as his father had purchased the struggling newspaper The New-York Tribune upon the death of its founder Horace Greeley. In 1918, Ogden asked Helen to come work as an advertising solicitor and she revitalized the flagging paper, eventually playing an instrumental role when the Tribune merged with the New York Herald. Her own voice was heard in interviews, public addresses, and magazine profiles, in which she expressed modern, rational points of view, often linking journalism with higher education because both fields bore responsibilities to the general public. At the 1938 Southern Interscholastic Press Conference in St. Louis, Reid declared: “’Today, responsible newspapers carry the news on both sides of a controversy, whether it be politics, government or social changes of any sort, and with this service of complete information people are enabled to make up their own minds.’” She also said, “The newspaper of today is becoming increasingly like a university, in its function of gathering and transmitting knowledge” (New York Herald Tribune, November 5, 1938, 15).

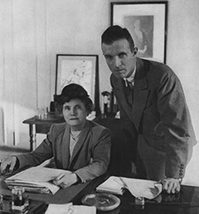

In 1945, Time magazine quoted her self-identifying as “Ogden Reid’s first mate” and described her office in detail: “Mrs. Reid calmly keeps two phones and two secretaries clicking all day. She never raises her voice, but it takes on a brittle edge when impatience brings a glitter to her grey-green eyes” (November 12, 1945, 73). When Ogden died in 1947, Helen immediately stepped in as president of the Herald Tribune, making her one of the most significant figures in 20th-century American history, particularly as one of the few women leaders in journalism.

Her prominence in American society cannot be overstated. Though she carried on her mother-in-law’s legacy of philanthropy, Helen also forged her own path in journalism, politics, and culture. Several times in the 1930s Reid was named among the ten most outstanding women in America, listed alongside luminaries like Amelia Earhart, Frances Perkins, and Eleanor Roosevelt. She graced the cover of Time magazine on October 8, 1934, pictured alongside Eleanor Roosevelt and Virginia Gildersleeve. But the photo was captioned “Helen Rogers Reid & Friends” and the accompanying article was all about the “Herald Tribune’s Lady.” In particular, it talked of Reid’s role as the host for the Herald Tribune’s annual conference, the Forum on Current Problems, which brought together women’s clubs and popular speakers to address contemporary issues. At the 1934 conference, held at the Waldorf-Astoria, speakers included Attorney General Homer Cummings, who talked about John Dillinger and crime; Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, who promoted unemployment insurance; and Frau Mathilde Wurm, a Jewish politician who had served as a Socialist member of the Reichstag, but was living in exile because of the Nazis, and warned against the perils of Hitlerism. The rest of the article takes us from the conference to Helen’s corner office at the newspaper, supposedly “a man’s room. Seated in a man’s chair, at a man’s desk, Mrs. Reid looks singularly small and frail. Tiny she is; frail she is not” (60). Most writing about Helen Rogers Reid fixated on her small stature and petite frame but the force of her personality and of her social impact was never underestimated. Reid possessed “innate efficiency, ambition, and commonsense” and she remained the unparalleled leader of the newspaper’s advertising sales force, whom she fired up with pep talks each Monday at 9 a.m. (60-61).

Eventually, the Forum on Current Problems gave way to a Youth Forum, established in 1955 to educate and engage the American journalists of tomorrow. Helen believed that future generations could learn much from the successes and failures of great men and women who had come before them, leading her in 1953 to donate the papers of Whitelaw Reid, Elisabeth Mills Reid, and the rest of the family to the Library of Congress for posterity. Around this same time, she decided to resign as chairman of the board of the Herald Tribune. Helen was nearing retirement and her sons had matured into capable newspapermen in their own right. In her statement, she declared it time “to give the younger generation a chance at running the paper,” with elder son Whitelaw taking over as Editor and the younger son Ogden becoming the president and publisher (Time, April 18, 1955, 58). She had secured the paper’s readership of suburban, middle-class subscribers, including women, but left her sons to determine the way forward for the Herald Tribune in the second half of the twentieth century, even if she was to retain a seat on the board for several more years.

Perhaps because she had not grown up with the wealth and privilege that came with her marriage, Helen was never very impressed or concerned with the finer things in life. One amusing anecdote came when she lost a $2,000 brooch in the East River in 1938. While enjoying a ride on a yacht, her blue silk hat, upon which the diamond and crystal brooch was pinned, blew right off her head into the river. According to The New York Times, the brooch contained 92 small diamonds with a total weight of eleven carats (August 10, 1938, 2). Naturally, the loss was reported to the police but it is unclear if the piece was ever recovered.

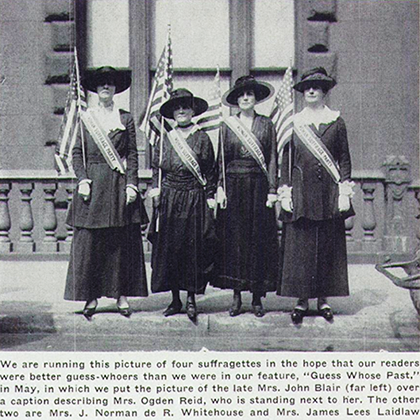

Helen was passionate throughout her life about various social causes. An ardent supporter of women’s suffrage, Reid raised nearly half a million dollars to secure the right to vote for New York women. “When I was at Barnard, working my way through,” she explained later, “the necessity for complete independence of women was borne in on me” (The New York Times, July 28, 1970, 1). But her commitment to women extended beyond suffrage: she hired many female reporters and editors over the years, including Irita van Doren, who served as the Herald Tribune's book editor for nearly four decades. Helen was also elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950, she became a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1953, was active in the New York Newspaper Women’s Club, and was the president of the Reid Foundation, an organization which provided fellowships for journalists to travel abroad. Another of her extraordinary endeavors was helping establish the Fresh Air Fund, a program which raised money to send inner city children to summer camps and homes in the country. Many urban children had never before escaped the sprawl and concrete heat of summer, making the Fresh Air Fund an extremely popular and long-running charity.

Though she took on her most significant role as the chair of Barnard’s Board of Trustees in 1947, Helen was a lifelong patroness and regular contributor to her alma mater’s events and publications. She served on the Board from 1914 until her retirement in 1956, when she stepped down as chair and was replaced by Samuel R. Milbank. Helen also helped raise funds for a Barnard dormitory completed in 1963 and named for her. A brick and limestone structure at the northwest corner of Broadway and 116 St., Reid Hall still houses undergraduates fifty years later, and marks the boundary between Barnard’s campus and the greater Morningside Heights neighborhood.

In the 1940s, Helen served on the advisory board of the Barnard College Alumnae Magazine and penned an article in the April 1943 issue in memory of her beloved former zoology professor, Dr. Henry E. Crampton. Reid shared in her essay how remarkable it was in the very early twentieth century to learn from him the theory of evolution: “No doubt today the general theory of evolution is as commonplace to a freshman and taken as much for granted as woman’s right to vote, but in the early 1900s neither, in a popular way, was considered quite respectable or possible of coexistence with orthodoxy” (7). She went on to praise the extraordinary education Barnard graduates received and the role Prof. Crampton played in shaping the college’s philosophy: “We hold a proud conviction that the fundamental and outstanding characteristic of the Barnard graduate is a free mind and in this achievement Professor Crampton has played a part that may well be immeasurable” (8).

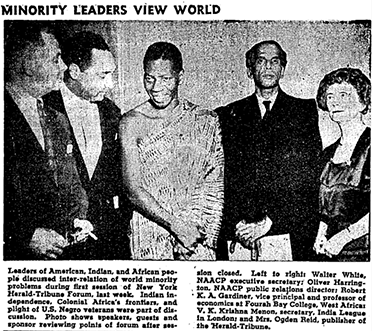

A lifelong Republican with close ties to President Eisenhower, who had also been president of Columbia University, Helen Rogers Reid was known to embrace racial equality, civil rights, and international causes. She was awarded the Comendador Cross of the Order of Honor and Merit from the Cuban Red Cross (on behalf of the Cuban government) for her “‘helpful understanding of world problems and friendliness toward Latin America’” (New York Herald Tribune, November 7, 1937, 18). Then, with World War II raging, Reid addressed an audience in Connecticut about Hitler: “We are confronted with the power of a psychopathic madman who has hypnotized 80 million people. We feel we were taken unawares, but we ought not to have been surprised” (Hartford Courant, June 6, 1940, 6). In 1945, Paul Robeson was featured at Reid’s annual Forum on Current Problems and, in 1948, Reid was invited to the 80th birthday celebration of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois in New York, though she could not attend due to a prior engagement.

At a 1943 Barnard forum chaired by Dean Gildersleeve, at which Dorothy Leet also spoke on international relations, Helen Rogers Reid passionately championed racial equality in the United States. Reid argued that before the U.S. could truly “lead the world,” we as a nation had to “learn the lessons of democracy at home and the first of these is to give all races equal opportunity for development” (Barnard College Alumnae Magazine, April 15, 1943, 13). Citing Dr. George Washington Carver as an example, Reid argued that African Americans, who were less than a century removed from the horrors of enslavement, had “only to be given a fair chance in order to add greatly to the sum of human achievement” (13). She also credited Mme. Chiang Kai-Shek as the foremost woman fighting for the cause of racial cooperation in the world. During this tense wartime period, Reid was invited to a dinner at the White House by President Roosevelt and was seated next to Winston Churchill; she apparently confronted him about the Indian fight for independence from British rule, a cause which she ardently supported. Legend has it that Churchill made light of her questions by asking which Indians she meant (a reference to the horrific treatment of Native Americans in the U.S.).

Reid was an avid traveler and a firm believer that travel fostered cross-cultural understanding and peace. In 1947, she joined a group of newspaper editors and publishers, all men, on the inaugural flights of the Pan-American Airways Clipper America, the first commercial airliner to make a trip around the world. She spoke about her varied experiences at a tea for the National Council of Women in July 1947, claiming that world travel could prevent future isolationism. “Mrs. Reid said that flying ‘makes one lose all sense of national boundaries, and feel the ridiculousness of national lines’” (New York Times, July 22, 1947, 20).

When she wasn’t traveling around the world, Helen spent most of her time at her luxurious coop, 834 Fifth Avenue. She also entertained guests at the family’s New York townhouse, 15 East 84th Street, as well as the 30-room Ophir Cottage estate in Purchase, New York, a summer retreat somewhere in the Adirondacks, and a hunting lodge in North Carolina. Her dinner parties were legendary and the attendees diverse; Reid always included her own editors and columnists but there were also Upper East Side socialites, famous authors, international statesmen, and economists. According to The New York Times, “With dessert, Mrs. Reid would swizzle a glass of champagne with a piece of melba toast and throw out general questions on current affairs. Going around the table, she would call on the diners, one by one, for their views” (July 28, 1970, 1).

Helen Rogers Reid died in 1970 of arteriosclerosis at the age of 87. Her obituary in the New York Times, published on the front page as a signal of her importance in twentieth-century America, characterized her as "an unflamboyant but powerful force in the newspaper world and in the city's civic and social life" (July 28, 1970, 1). Her will was detailed in the New York press, with a $200,000 bequest going to Barnard, $100,000 to the Fresh Air Fund, $10,000 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the bulk of the remaining estate to be distributed among her sons, daughters-in-law, and her 10 grandchildren. The daughters-in-law each received $50,000 as well as many exquisite pieces of Helen’s jewelry, some having been passed to her from Elisabeth Mills Reid (New York Times, August 8, 1970, 20).

Mrs. Ogden Reid, now President of the New York Herald-Tribune, was a graduate of Barnard College of Columbia University, deeply interested in international affairs and naturally associated with the small group of American university women who saw a vision of what this Paris centre might accomplish. To her also Reid Hall owes a great debt (Virginia Gildersleeve, 1950).

So what about Reid Hall in Paris, and the legacy of Helen’s mother-in-law, Elisabeth Mills Reid? The woman who had changed Helen’s life and who had instilled in her a commitment to philanthropy and education remained her most beloved guiding force throughout her long and varied career. Helen kept a large portrait of Elisabeth on the wall of her office at the Herald-Tribune for many years, positioned behind her desk and directly above her, like a guardian angel benevolently watching while the paper and its fearless leader evolved. Helen also carried on the work that Elisabeth had begun in Paris when she first leased 4 rue de Chevreuse in 1893. She worked closely with Dean Gildersleeve, Carey Thomas, and other leaders in higher education to convince Elisabeth in 1922 to convert the former Girls’ Art Club into an experimental University Women’s Club, meant to be a headquarters for college women all over the world to meet, exchange ideas, and continue their work. Helen remained on the board of the University Women’s Club for several decades, even after Elisabeth’s death in 1931, and helped see 4 rue de Chevreuse, by then renamed Reid Hall, through the Great Depression, World War II, and the postwar years, alongside Gildersleeve and Dorothy Leet. Her efforts with Reid Hall and the continued success of the Herald-Tribune’s European edition, based in Paris, led the French government to honor Helen as an Officer of the Legion of Honor on November 3, 1947, decorated in New York by French Ambassador Henri Bonnet.

Perhaps most significantly, it was Helen Rogers Reid who secured the future of Reid Hall. In a surprise move unbeknownst to the board and even Dorothy Leet, she permanently transferred the property to Columbia University in 1964, thereby ensuring that study abroad, college women, and international cooperation would remain the essential focus of its activities. Ever the practical businesswoman, Helen stipulated that if Columbia ever sold 4 rue de Chevreuse, the profits must be evenly split between Columbia and Barnard. Let us all hope this never comes to pass!

Sources

- Barnard College Alumnae Magazine, volume XXXII, number 4, April 15, 1943. Internet Archive.

- “Barnard to Name New Dormitory Helen Reid Hall.” New York Herald Tribune, March 29, 1961, p. 23. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- By Special Wireless. “Mrs. Ogden Reid Given 1935 Award by Women’s Ass’n.” New York Herald Tribune (European edition), November 20, 1935, p. 1. Gale Primary Sources.

- “Brown & White at the Trib.” Time, April 18, 1955, volume 65, issue 16, p. 58.

- From the Herald Tribune Bureau. “France Honors Mrs. Reid.” New York Herald-Tribune (European edition), November 4, 1947, p. 1. Gale Primary Sources.

- "Centinel Hill Hall Opened at Fox Store: Auditorium is Designed to Commemorate Local Founders of American Democracy Women of State are Paid Honor Mrs. H. R. Reid of New York Herald Tribune; Mrs. B. F. Auerbach, Company Head, Speak." The Hartford Courant, June 06, 1940, p. 1. ProQuest.

- Doenecke, Justus D. "Reid, Helen Rogers (1882-1970)." Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, CT: Yorkin Publications, 1999.

- From the Herald Tribune Bureau. “Late Whitelaw Reid’s Papers Given to U.S.” New York Herald-Tribune (European edition), September 18, 1953, p. 1. Gale Primary Sources.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia. "Tribute to Helen Rogers Reid," 1950. Reid Hall archives.

- “Herald Tribune’s Lady.” Time, October 8, 1934, volume 24, issue 15, pp. 59-62.

- “Milbank to Head Barnard’s Board.” The New York Times, December 13, 1956, p. 39. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Mrs. Ogden Reid Dies Here at 87.” The New York Times, July 28, 1970, p. 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Mrs. Ogden Reid Loses $2,000 Brooch in River.” The New York Times, August 10, 1938, p. 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Mrs. Roosevelt Receives Medal Of Honor From Cuban Red Cross: Mrs. Ogden Reid Honored for Her 'Understanding' of World Problems.'” New York Herald Tribune, November 7, 1937, p. 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Special to the Herald Tribune. “South’s School Editors Open Annual Session.” New York Herald Tribune, November 5, 1938, p. 15. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “The Trib’s Mrs. Reid.” Time, November 12, 1945, volume 46, issue 20, pp. 72-74.

- “Will of Mrs. Reid Filed for Probate; Barnard Will Gain.” The New York Times, August 8, 1970, p. 20. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “World Travel Can Prevent Isolationism, Mrs. Reid Says in Describing Air Trip.” New York Times, July 22, 1947, p. 20. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.