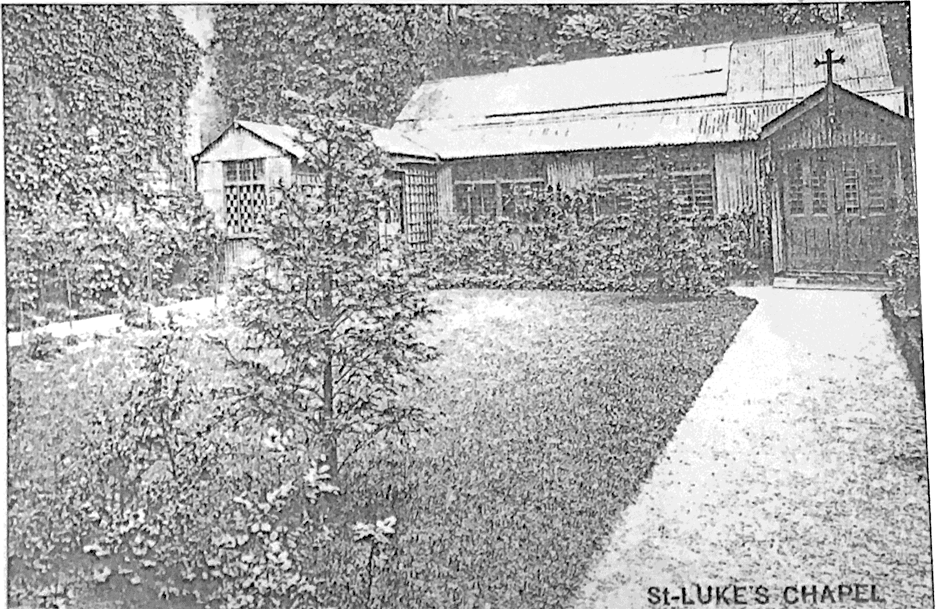

St. Luke's Chapel, 1892 – 1934

St. Luke's Chapel, affectionately known as "the Little Tin Church" or "St. Luke's in the Garden," was a prefabricated structure located in the back garden of the property at 4 rue de Chevreuse. From 1892 until 1934, it served the continually-burgeoning population of American students in the Latin Quarter. Directly connected to the American Cathedral in Paris (the Church of the Holy Trinity), St. Luke's also maintained a symbiotic relationship with the neighboring American Girls' Art Club and its later iteration as the University Women's Club, as well as with the American Art Association of Paris (AAAP).

The Early Years

In this colony of students, far removed from their homes and home influences and in the midst of the many and subtle dangers of a large city, stands our little church, reminding those who are absorbed in the pursuit of painting, sculpture, architecture, music, language, and other departments of study, of God and His Church, of the spiritual demanding culture and development as truly as the intellectual and technical. [The Living Church (1904) 86]

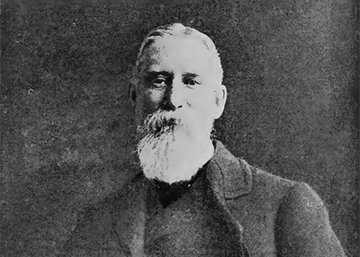

In the fall of 1889, when Presbyterian minister William Whitney Newell and his wife Helen began hosting student gatherings in their apartment on the Boulevard St. Germain, the Church of the Holy Trinity quickly took notice and began subsidizing their efforts (see American Girls' Art Club). The church’s financial support increased when the Newells moved to a larger apartment at 87 rue de Rennes. Soon after, they proposed to Holy Trinity the establishment of a religious service on the Left Bank, somewhere in the Latin Quarter, where so many students lived and worked in the "American colony." The Newells also found a friend in A.A. Anderson, then president of the American Art Association of Paris, and in Elisabeth Mills Reid, a long-time parishioner at Holy Trinity, who was confirmed there in 1874, in the same class as famed artist John Singer Sargent.

William W. Newell, a lay-reader licensed by the Bishop of Holy Trinity, began offering formal church services at 56 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in the fall of 1891. Since the first mass was held on St. Luke's Day, October 18, 1891, it was only fitting to name the entire venture after St. Luke, patron saint of artists, students, and physicians. In the early years, weekly Sunday services were held at 11am, with Holy Communion celebrated on the second and fourth Sundays of the month.

A beautiful altar-cross and candlesticks, in brass, the work of Messrs. Barkinton and Krall of London, have been presented to St. Luke's by a member of our congregation [...] The large windows of the studio in which temporarily the services are held have been beautifully decorated by one of the congregation, Mr. Malcolm Fraser, an American artist living in the quarter. Upon one he has painted a representation of the Annunciation, and upon the other a representation of the Nativity (Parish Kalendar, February 1892, as quoted in Allen 450).

Newell was ordained to the deaconate on May 8, 1892, and Holy Trinity soon formalized the relationship to his Latin Quarter church services, which became officially known as St. Luke's Chapel of the Church of the Holy Trinity on July 14, 1892 (Allen 451). That same summer, a new site for the chapel was found at 5 rue de la Grande Chaumière. Rev. Dr. Morgan, cousin of the famous financier J.P. Morgan and rector of Holy Trinity, leased the plot of land from J.J.E. Keller, the son of Jean-Jacques Keller, who had founded the Keller Institute (Allen 451).

A corrugated iron building, the "Little Tin Church," was anonymously donated by a Holy Trinity member. St. Luke's had outgrown its former space on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs and the new structure could comfortably seat 150 people. Rev. Dr. Morgan led the first service in the new St. Luke's on Sunday, November 13, 1892 at 11am, assisted by Rev. Newell, in front of a standing-room-only crowd. In an article in The Independent, Rev. Wilberforce Newton, who attended a mass at St. Luke's in 1895 (with nearly one hundred artists present), recorded some of the remarks made by Rev. Dr. Morgan: "It will be a great thing if we can help to give art a Christian tone [...] for it will help in the work of making America over again. Therefore let us begin with the artists here" (13). Rev. Newton also described a painting of Christ walking among the lilies as one of the lone adornments in the simple chapel.

The rest of the property of the former Keller Institute surrounding St. Luke's, including all of the buildings and the garden at 4 rue de Chevreuse, was leased to Elisabeth Mills Reid in 1893. According to the New York Herald, she had partially contributed funds toward the erection of the chapel, which became an integral part of everyday life at the Club (April 30, 1931, 3).

Rev. Newell died on January 23, 1894 and was originally buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse. He was replaced by Rev. S.P. Kelly, former rector of St. John's Church in Philadelphia, who had spent time in Paris a few years earlier. Kelly resided at 79 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs and remained at St. Luke's until September 1896. During Rev. Kelly's tenure, a brass chandelier was donated to the Chapel by a member of the congregation (Parish Kalendar, August 1894, as quoted in Allen 456). In his parting sermon, Kelly defended the Paris community of American artists whose behavior had been criticized by the Rev. Dr. Charles Wood in Philadelphia as well as in several published articles:

[...] American art students at Paris are known for religious consistency and good behavior; they largely attend religious services; their moral tone is excellent. Such a 'bold, bald statement' as Dr. Wood's 'needs to be contradicted flatly.' They are hard workers and find no time for gay and giddy experiences (Allen 457).

Kelly was replaced for several months by Rev. Hayward, "on loan" from Holy Trinity, and he oversaw upgrades to the Chapel's material structure. Rev. Isaac Van Winkle then took over as minister of St. Luke's on March 29, 1897. He was deeply engaged with the students and artists under his pastoral care and remained at St. Luke's for nearly 20 years, residing just across the boulevard du Montparnasse at 11 rue Léopold Robert, and later at 125 boulevard du Montparnasse. In 1898, he raised funds to incorporate a pipe-organ into the chapel and regularly solicited economic assistance from members of Holy Trinity's wealthy congregation. Around 1912, St. Luke's was further enriched with a gift of "choir stalls in rich old dark oak of the Eighteenth Century" from Messrs. Gaudin, esteemed stained glass artists, which were placed on either side of the altar. A Mrs. Villers-Forbes also donated "an excellent Alexandre harmonium" around the same time (Allen 479). The renowned Gaudin ateliers were located across the street from the Chapel at 6 rue de la Grande Chaumière.

Rev. Van Winkle wrote an impassioned article in Ladies' Home Journal in June 1903 defending the lifestyles and social mores of young American women living in Paris, aiming to reassure parents back home that the Chapel ensured their virtue. But, in the same article, he did not recommend artistic careers for women:

To girls who are attracted by art or music, it must be said: ‘Look about you. What are the results?’ Successes are not so numerous as to warrant a rash rushing into one or the other as a profession. There is a demand for teachers, but apart from this there is perhaps no career for a girl in the which the steps are so slow as art or music (17).

Van Winkle's community engagement seems to have focused more on male artists and art students than on their female counterparts. He founded and oversaw the St. Luke's men's reading rooms and developed strong ties with the AAAP, the male equivalent of the Girls’ Art Club. Despite his overt penchant for male artists, Van Winkle was nevertheless beloved by the American colony for his dedication and kindness. His lengthy curacy at St. Luke’s ended on May 4, 1914, just before World War I. As Van Winkle prepared to return to the U.S., an outpouring of emotion was communicated to the New York Herald European bureau in the form of letters bearing witness to his unstinting devotion. Artist Theodore Spicer-Simson lauded his kindness:

He is beloved by all who knew him. That means practically every American student and every American who has passed anytime in the ‘Quarter.’ He is kindness itself. […] He is always attentive to young men’s problems. He knows how to deal with them. Understanding students, he does not attempt to thrust religion down their throat or court admiration for brilliant preaching or seek glory in an atmosphere of social snobbishness (July 27, 1914, 3).

Others also expressed their admiration for his ability to be a friend who did not allow his role as minister to overshadow his humanity:

Mr. Van Winkle worked humanly and that is the secret to his success and of the friendship and confidence students and others have for him. He and Mrs. Van Winkle did a host of things, little friendly services, homely services, of a sort no minister could rightly expect to do. I am sure that all the Americans in the Latin Quarter will feel when the Van Winkles go as though a parent has been taken from them (July 27, 1914, 3).

Van Winkle returned to the United States with his wife and their five children. He served as rector of St. Clement's Church in New York City until his death in 1917. An obituary in the New York Times reported that he had graduated from Columbia College in 1865 before attending the General Theological Seminary (11).

Activities at St. Luke's

I went to St. Luke’s Chapel Sunday morning and enjoyed the service very much. It is just back of the girls’ club… and well heated. It is only plain boards, no paint, but has stained glass windows and back of the alter [sic] a lovely piece of Tapestry, so soft and beautiful in color (Anna McNulty Lester, 1898).

In a 1902 issue of the Parish Kalendar, the Church of the Holy Trinity reflected on early efforts by St. Luke’s chapel to meet the varied needs of its congregants:

Its work is so much more than the rendering of public worship. The work of any church, true to itself, true to its responsibility, must be more than worship. So St. Luke's stands ready to be a friend in whatever direction a friend may be needed. In this it is largely your trustee, to minister in trouble, sickness, need, or other difficulties [...] Its colony is practically an Anglo-American University in a foreign land, and St. Luke's is practically a University Chapel (cited in Allen 464).

The American Art Association of Paris (AAAP), which supported Rev. Newell's religious services and social endeavors, hosted a reception at its headquarters at 131 boulevard du Montparnasse for the Chapel's inauguration. The AAAP continued its relationship with the Chapel for several years (Allen 456). In describing the activities co-hosted by the chapel and the AAAP, Ann Merriman wrote in Quartier Latin that they were the "spiritual backbone to this busy community" (666).

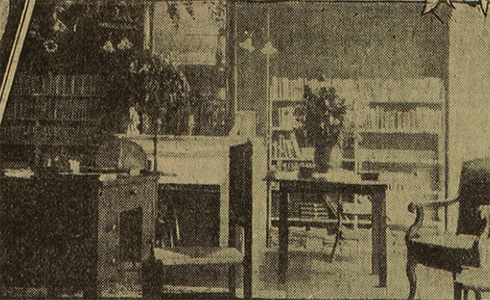

One of the chapel’s key initiatives was to maintain reading rooms for male art students in the neighborhood. The history of these reading rooms is intricately tied to the trajectory of the AAAP. First opened by the Newells at 19 rue Vavin, the reading rooms also provided Sunday evening social services before the idea of a chapel had even been conceived. Once the AAAP’s headquarters on the Boulevard du Montparnasse were established in 1890, the Vavin reading rooms were closed and religious services were moved to the temporary St. Luke’s space on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. When the AAAP vacated the Latin Quarter, Rev. Van Winkle created the "St. Luke’s Reading Rooms" in January 1901 at 14 rue de la Grande Chaumière. Since the Girls' Art Club had a well-stocked and frequently-used library, the St. Luke's Reading Rooms were reserved for men (Harper’s Guide to Paris 196). They were moved to 132 Boulevard du Montparnasse in May 1901 before closing in 1902, when the AAAP returned to the Latin Quarter. Unfortunately, the AAAP closed down for good in 1909, so the St. Luke’s Reading Rooms reopened in February 1910 at 70bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, only to move once more in 1912 to 6 rue Huyghens, where they remained until the outbreak of WWI (Allen 477).

A brief 1911 article in Living Church described the modus operandi of these reading rooms:

Ten francs a year, less than $2.50, gives young men the right to turn in there, find warmth, a well-stocked library, the best newspapers and magazines, chess and other games, a pianoforte, and sociable company. As for the exhibition, the pictures on view were, as expected, not so much an exhibition of remarkable paintings as a collection of efforts and studies [...] Part of the proceeds of the exhibition sales are to go to the reading-room funds. One feels what a blessing such rooms must be for young men, strangers in a strange land. In return for the ten franc fee, each member receives a key; he depends on no one therefore to let him in. Accessible all day long and late into the evening, men can turn in there away from the discomfort of a cramped logement [...] (Wolff 155).

Aside from the reading rooms, the Chapel's religious services and social activities made it a home away from home for so many young Americans in Paris. In September 1902, Geraldine Rowland documented the Chapel's centrality to the lives of the American student community for Harper's Bazaar: "... on Sundays, the Episcopal students come from various parts of Paris to make good resolutions. Or, as sometimes happens when Cupid interrupts the progress of art, they come to be married. Here as well are the children of the Quarter baptized" (758).

Independent scholar John Crombie discovered that the St. Luke's ministry expanded beyond American students and "assumed a more dynamic role in the neighbourhood's daily life, manifested in a practical concern for the bodily welfare of [the] regiment of models. In 1904 it held the first of a regular series of Epiphany Festivals for child models in a large studio...graciously lent by Colarossi for the purpose" (111). Allen described the 1910 festival:

About 150 children were assembled in the large studio of the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, kindly given for the festival by the management. As many as 150 more gathered to help and see the children made happy. Each child received a large bun, a package of candy, an orange and a gift - toys, dolls, and useful knitted articles prepared by the Sewing Society at Holy Trinity Lodge. The expense was largely contributed by students and artists (473).

Another description of St. Luke's from the 1912 book, Footprints of Famous Americans in Paris, best summarizes its impact on the student community and neighborhood:

St. Luke's Chapel is something one would not expect to find in the Quarter. It looks like a country church; and gives a Christian tone to the whole neighbourhood. [...] Here the preacher paws the air and popularizes and Christianizes principles of pagan philosophy. Here queer pictures, far from representing Calvary or the Way of the Cross, decorate the walls. Here some professional singer or fascinating female student of song entertains the audience with her thrills and her frills. A reception is held after the services. The preacher and the singer are congratulated; and newcomers are welcomed. It is a capital entertainment. American students celebrate national holidays, such as the Fourth of July, Thanksgiving Day, Washington's Birthday, and Lincoln's Birthday. Nowhere else is the banner of the Stars and Stripes hung more profusely on the outer walls; nowhere else is the Star Spangled Banner sung with more enthusiasm. To make the Thanksgiving Day dinner as homelike as possible the Art Students' Club of New York has been known to send over American turkeys, while distinguished ladies of the colony have supplied cranberry sauce, sweet potatoes, green corn, mince pumpkin, lemon and apple pies, and other eatables peculiar to the United States (Conway 245-246).

During World War I the property surrounding the Chapel had been converted first into a French military hospital, then an American military hospital, and, finally, the European headquarters of the American Red Cross. The Chapel building itself was used to house wounded soldiers. After the war, St. Luke's was reconsecrated as a religious institution, ministering to a new generation of Americans in Paris. By 1926, it was declared by a certain Dr. Paul Van Dyke the “spiritual heart of the Latin Quarter” (Allen 502).

Holy Trinity Lodge

Since it was generally known that most St. Luke's initiatives catered to male students, Holy Trinity established a lodge for women at 70bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in 1905. It included "[...] 'an apartment with studio attached.' This was to be a 'home-like gathering place for English-speaking women'" (cited in Allen 469). Headed by Deaconess Jessie Carryl-Smith, a graduate of the New York Training School for Deaconesses (NYH Euro, November 16, 1913, 2), the Lodge was an auxiliary to St. Luke's that included a medical ward for female students, an information bureau, reading materials in English and French, and a clothing bureau.

The whole place is charming – large and comfortable studio, where tea is served gratis to all American and English students, every afternoon between five and six o’clock, the picturesque court, with its old ivy-mantled tower, the cozy dining room, where coffee is served gratis to students every Sunday morning after the service at St. Luke’s Chapel; the wholesome and artistically furnished bed-rooms with windows overlooking the court, all combine to make Holy Trinity Lodge that which it is designed to be – a place of rest, recreation, and genuine home comforts (Leonard 6).

The Lodge gained popularity with the Anglo-American community in the neighborhood and quickly outgrew its original quarters, moving to more spacious accommodations at 4 rue Pierre Nicole, near the Observatoire, in 1906. Prior to its move, 37 women who suffered from a variety of ailments, some of which were quite serious: malaria, nervous breakdowns, typhoid, etc., had received treatment.

In 1907, the Lodge leased the large garden of a Carmelite convent on the rue du Val de Grace (Allen 476).

It is a little oasis of verdure such as dwellers in great cities keenly appreciate, and it has historical associations of the highest interest. [...] On the ground floor of the Lodge, which has a house to itself, is a large studio where Mr. Rubert Bunny holds a painting class daily [...] On a floor above, are two large rooms. One, called the reading room, is a marvel of taste and neatness [...] Beyond is a large studio available for portrait work between certain hours, and used for the Sunday evening religious services. Still higher, we come to the dining room and consultation rooms and the hospital. The first is a lofty cheerful apartment in which meals are served to about a dozen regular boarders. Across the hall is the hospital. [...] The Lodge also possesses a clinic (NYH Euro, June 24, 1907, 6).

Financial support from donor Helen Gould enabled the Lodge to expand its medical services in a larger space, which was inaugurated in 1907 with religious ceremonies, music, and tea. American ambassador Henry White and other dignitaries of the Anglo-American colony attended the festivities. The New York Herald European edition covered the event and reported on the hospital’s facilities and welcoming atmosphere:

There is an operating room, a sterilizing room, several private bedrooms, and a convalescing ward, which contains five beds. At present there is room in the hospital for eight patients. All is bright and white and clean. A glance at the rooms and a talk with the nurses are almost sufficient to make the visitor wish for illness and a period of attendance in such an inviting place (October 3, 1907, 6).

Two of the hospital’s eight rooms were reserved for men “[…] for it has been found that the condition of the men when ill is even more pitiful than that of the women, and the rooms are continually full” (Rev. Dr. Morgan quoted in NYH Euro, November 16, 1913, 2). The hospital was non-denominational and open to the entire English-speaking community in Paris. More importantly, care was dispensed free of charge. Those who could afford to pay were asked to make a donation.

By 1910, the hospital had treated 225 patients.

In later years, the Lodge expanded its other services to the American and British student community, adding a circulating library, an education department, a painting club, a choral club, and even a Bible class. The Lodge and St. Luke's jointly hosted annual Christmas-Epiphany events, featuring mass, carols, and feasts. There were also musical and social gatherings every Wednesday and various other parties with concerts. By 1911, the library boasted 8,000 volumes (Allen 479).

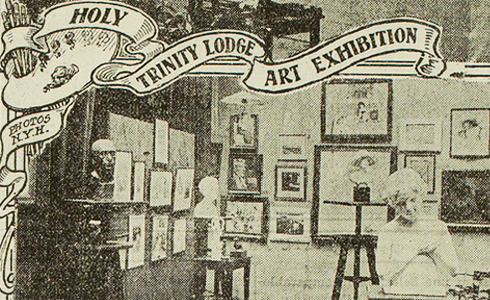

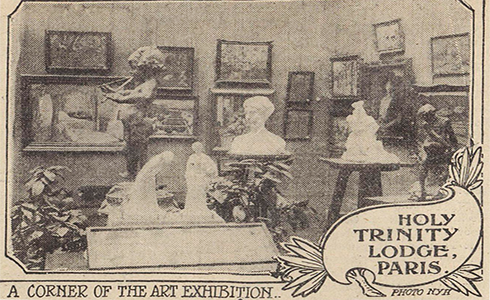

Art and artists were always central to the Lodge’s operations. In 1907, an Art League for women was formed, a rival organization to the American Woman's Art Association, housed at 4 rue de Chevreuse. Headed first by Elizabeth Nourse, then by Florence Esté from 1908 – 1913, the League sponsored annual exhibitions (mainly in February), which drew an average of 200 submissions, though only 75-100 were ultimately selected. In 1909, the League also organized a special exhibit of the works of New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins. Each exhibition was inaugurated with an address by the American ambassador, a concert, and tea. In its last years, the opening events drew as many as 500 people. Open daily from 2pm-5pm, the exhibitions usually lasted for two full weeks and featured paintings, drawings and engravings, sculptures, and "objets d'art." These shows were often favorably reviewed in The New York Herald European edition, although many comments by male reviewers would be unacceptable from a modern perspective, i.e. "In the broad, vigorous treatment of the subject there is a seemingly masculine touch that, unsigned, few would attribute it to a woman. Bold the sweeping lines, vivid the color and strength of expression make this a remarkable picture" (said of the paintings of Cornelia Cowles, February 6, 1910, 6).

Although it had achieved great success and was a real resource for the American colony, the Lodge could not sustain itself long-term. Whether due to lack of funding or competing organizations in Montparnasse, it closed its doors in 1913. The opening of the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1910 had led to the consolidation of medical services for the American colony and contributed to Holy Trinity’s decision to shut down the Lodge. According to the New York Herald European edition, members of the Anglo-American colony in the Latin Quarter voiced their “[...] consternation at the thought that an institution should be closed which for nine years had filled so important a place in the community and has indisputably been the salvation of many a suffering and unfortunate American student.” (November 16, 1913, 2).

The loss of the Lodge’s medical services seriously impacted residents of the Left Bank: many claimed that the American Hospital in Neuilly was too expensive and required signed affidavits attesting to one’s poverty before treatment could begin. To address these concerns, the medical clinic at 4 rue de Chevreuse enhanced its services with the addition of a visiting nurse from the American Hospital.

WWI and Postwar

During World War I, Elisabeth Mills Reid transformed 4 rue de Chevreuse into a military hospital and St. Luke's Chapel was converted into a ward for convalescing soldiers (Congressional Record – House 1074).

Religious services resumed at St. Luke's in 1919, six months after the Armistice, but a Vicar-in-Charge was not appointed until October 1920. A rapid succession of clergymen oversaw the Chapel's services and activities in the succeeding years. As St. Luke’s resumed ministering to the spiritual needs of the American community in Montparnasse, its managing committee sought new ways to expand the social headquarters "for the vicar and his student work" (Allen 652). The committee attempted to convince Elisabeth Mills Reid to build a second temporary structure as a clubhouse in the garden at 4 rue de Chevreuse but she refused, in part because she had spent a considerable amount of money restoring that garden after the war.

By 1922, the Chapel’s social footprint had grown considerably so Holy Trinity secured a space for its own club at 107 Boulevard Raspail, not far from the St. Luke’s. It was inaugurated on Easter Monday, April 17, 1922, under the name of The American Students' Club (later it became the U.S. Students' and Artists' Club). Allen cites a description of the Club that had been published in the Holy Trinity Yearbook of 1922:

The rooms were crowded with organizers, students and artists. There is a large general room, a reading and writing room, a billiard room, and the Chaplain's office. In the basement will be a small gymnasium, with shower baths [...] The rooms are comfortably and attractively furnished [...] Its object is "to bring within its sphere of influence the greatest possible number of American and British students and artists" (653).

Student receptions and dinners followed by concerts were held in the assembly room at 4 rue de Chevreuse and also at this new clubhouse. Sunday evening concerts and Thursday afternoon tea dances brought together scores of young people. Thanksgiving and Christmas festivities were also major events in the community. In addition, St. Luke’s supported the medical clinic at 4 rue de Chevreuse, organized a sewing society, and established a partnership with the American Library in Paris.

The clubhouse at 107 boulevard Raspail was enormously popular and quickly outgrew the space. Before exploring other options, Holy Trinity proposed an ambitious plan for "a 'complete church plant' on the Reid property" in 1926 (Allen 656). If they could convince Mrs. Reid to sell her land, they planned to overhaul a good portion of the property and add a new chapel, art studios, improved accommodations for 75 students, a cafeteria, a library, a gymnasium, and a new medical clinic. Though Reid did seriously consider Holy Trinity’s proposal, she decided that the American University Women's Club was the more worthwhile endeavor and declined to sell (Allen 656). Holy Trinity then focused its efforts on securing a new location elsewhere in the neighborhood.

Despite these protracted negotiations and the uncertain future of the Holy Trinity Clubhouse, the Little Tin Church remained a beloved part of life at the University Women's Club and in the larger Montparnasse community. Hope Mirrlees, a resident at the Club from 1922-1925, wrote at length about St. Luke's in her memoirs:

A little tin chapel was another of the ornaments of the garden – a humble vassal of the great American Episcopalian Church at the Etoile. On the principle of suave mari, it was very pleasant to sit of a Sunday morning in the arm-chairs of our comfortable study and listen to the strains of the Te Deum and of the Church’s One Foundation, and, particularly, to the scrapings and shufflings of the congregation as they performed the exhausting gymnastics entailed by the ritual of the Anglican Church. We were fond of that little chapel. It was certainly far from decorative, but it seemed as friendly as the Judas tree, and as much a part of the garden; though, from its vocal powers it had, perhaps, more in common with the innumerable cats who regularly held their concerts there every night of the week (93).

From St. Luke's in the Garden to the American Center

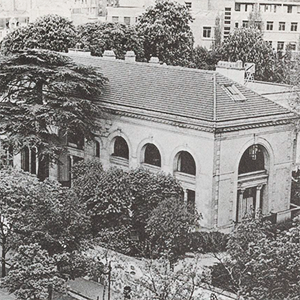

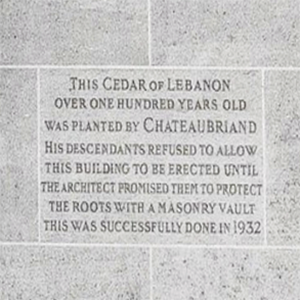

Holy Trinity began cementing plans in the late 1920s to transfer the entire St. Luke's enterprise to another location in Montparnasse. In 1929, the Church launched a fundraising effort centered on a "Student Property Campaign," an initiative to secure a large space where it could consolidate its religious and social work on the Left Bank (Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1929, 2, 8). In 1930, Holy Trinity found an ideal property: the Fondation Chateaubriand at 261 boulevard Raspail, which featured a centenary cedar of Lebanon and measured "[...] 4820 square meters with a frontage of 82 meters on the boulevard Raspail" (Allen 668). On April 1, 1931, Holy Trinity leased this massive estate for a term of 60 years and hired the American architect Welles Bosworth to design an edifice that would become The American Students’ Social Center (Delanoë 23), later renamed the American Students’ & Artists’ Center. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1932 and the building was opened on October 16, 1934. It housed a library, cafeteria, a billiard and ping-pong room, an assembly hall, artist studios, exhibition spaces, and a swimming pool.

While the new building and grounds were full of promise, a 1934 Parish Bulletin waxed nostalgic about the intimacy of the old Clubhouse at 107 boulevard Raspail:

[...] will the new club building, spacious, elegant, efficient, and completely satisfying as it is scheduled to be, be able to weld that strangely heterogeneous mass of spontaneous youth, middle-aged women, dogs, cats, babies, old men, and noisy children into one homogeneous whole, as 107 has so successfully done, and having done so, will one enjoy there, anything like that sense of vital, spontaneous, carefree informal life, that sense of absolute use, which for all of us who knew 107 spelt one word - HOME (Allen 675).

As time passed, its membership grew to seven hundred people who forged a vast community of shared interests and vibrant activities. The new center catered to the American colony until the onset of WWII, when the "building was taken over as French governmental offices [...] for the duration of the War" (Allen 684).

As for the Little Tin Church, its fate was quite different. Holy Trinity had planned to erect a chapel on the grounds of their new property and had already promised Elisabeth Mills Reid years earlier that it would dismantle St. Luke's. Though the exodus was planned before Reid’s death in 1931, a July 1933 letter from Rev. Frederick W. Beekman to Dorothy F. Leet, director of the University Women’s Club, explained why the move was delayed for several years:

I am a bit embarrassed in writing you this letter. You will recall that Mrs. Reid took up with me some time ago the date when we would give up the little chapel and vacate the premises [...] Owing to unforeseen delays [...] I am compelled to place the facts before you and to ask if you would be good enough to use your good offices with the officers of your association in granting us a little more time (Barnard College Archives).

Helen Rogers Reid, who had succeeded her mother-in-law, Elisabeth Mills Reid, agreed to extend the Chapel’s residency but asked that St. Luke's “pay taxes on their portion of the rue de Chevreuse/rue de la Grande Chaumière property, a request that had never been made before" (Allen 603), in order to stave off financial difficulties. Apparently, the Chapel's finance committee found this request to be reasonable and paid its share, 1,529.60 francs.

One year later, in a July 1934 letter to Dean Virginia Gildersleeve, another member of the University Women’s Club board, Rev. Beekman announced the formal closing of the Chapel:

On Sunday, the 22, will be held the last service in the 'little tin chapel' and we were planning to remove the building and its appurtenances during the week following. Of course, we shall take care of the expenses. Canon Belshaw, who is much au courant with the details involved and who is to be in charge of the moving will be in contact with Miss Leet within the next day or two [...] While I am writing I want you to know of the deep appreciation of the Vestry, including myself, for the uniform courtesy accorded us at all times by Miss Leet and the officers of Reid Hall since the last named have been the proprietors. We send you all out [typo for 'our'] best wishes for the continued success of your valuable center. Of course, Mrs. Reid’s memory will always be dear to us, as it was to our predecessors at the church and particularly to Dr. Morgan who, with Mrs. Reid entered into a real partnership for student work (Barnard College Archives).

In the summer of 1934, the baptistry, altar, lectern, and other Chapel accouterments were moved to the auditorium of 261 boulevard Raspail (Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1934, 2). A few months later, in October, the Little Tin Church was completely dismantled.

Consult the sources for St. Luke's Chapel