Florence Lundborg, 1870 – 1949

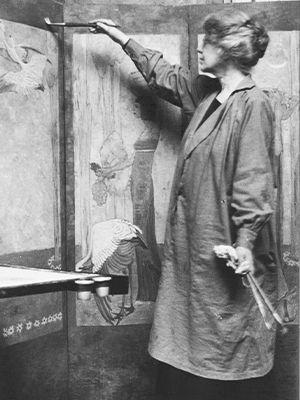

Unlike many of the artists whose lives we have chronicled, Florence Lundborg’s biography is quite extensive, although the record omits several important details, not the least of which was her residency at 4 rue de Chevreuse – a period that would fashion her future trajectory as an artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and muralist.

A comprehensive sketch of her career was published by Robert W. Edwards in Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, vol. one, available in digital facsimile on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website as an "Archived copy."

Edwards' essay is reprinted here in bold, with the author’s permission, interspersed with bulleted information gleaned mainly from newspaper articles. For the sake of readability, the endnotes and their numerical references have been removed. The full article, including the endnotes and sources, can be found on the TFAO website (see above).

FLORENCE LUNDBORG (1870 – 1949) was born in San Francisco on September 9th to an upper middle class family that resided at 1504 Taylor Street. According to the U.S. Census of 1880, her father, John Lundborg, was a Swedish-born dentist and her mother, Hattie, was assisted at home by a live-in servant. She had two brothers. Between 1893 and 1897 Florence received her early training in art at the local California School of Design under Arthur Mathews, Amédée Joullin, Oscar Kunath and Raymond Yelland. She shared a studio with three other women artists.

- Her work, “Study of an Oak,” was shown at the 1894 California Mid-Winter Exposition in San Francisco (Official History of the California Mid-Winter…123).

In 1895 she was awarded the W. E. Brown Medal in drawing from life and a year later received an honorable mention in oil painting. For the School’s “jinks programme” she read ghost stories to the banquet guests.

- The exhibition of the Mark Hopkins Institute attracted 1,500 people (San Francisco Examiner, May 21, 1896, 13).

Between 1894 and 1897 her contributions to the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA) were primarily still lifes, portrait sketches and interior studies in watercolor.

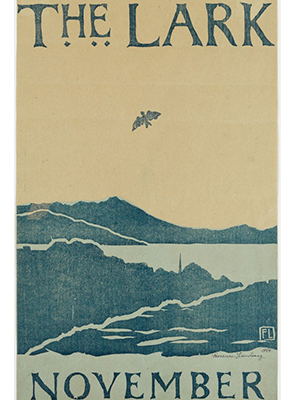

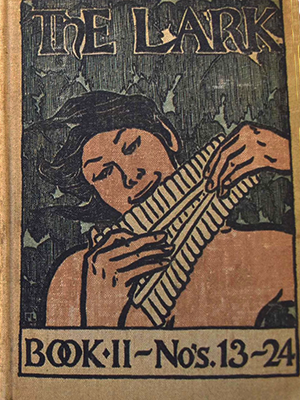

- During this time, she lived on Russian Hill and participated in the club “Les Jeunes,” which met for parties and other social occasions (Starr 26). Several members of the group also contributed to The Lark, described as a “dinky magazine” (Parker 50). Founded by humorist Gelett Burgess and published by William Doxey, it enjoyed great popularity in its brief lifetime between 1895 and 1897. Lundborg and other artists contributed drawings or prints that appeared as posters or as covers and illustrations for the 24 issues of the magazine.

- Among the female artists who worked for magazines, Florence Lundborg (1871-1949) is perhaps the most unusual. Rather than doing lithographs, she cut woodblocks for her posters that advertised the San Francisco miniature magazine, the Lark. This spirited little review, the brainchild of Gelett Burgess, managed to be simultaneously the most irreverent and most original of the ephemerals. Obviously able to hold her own among the male literati who congregated around the bookseller and mentor of the Lark, 97 William Doxey, Lundborg produced eight posters during 1895 and 1896 (Serwer 96-97).

In 1896 she contributed several of her highly coveted posters to an exhibit in the Mercantile Library of New York City and exhibited with the Sketch Club of San Francisco.

- “At the exhibit, she showed the original drawing, the wood blocks carved by herself and the reproductions” of the May and November numbers of The Lark (San Francisco Chronicle, November 19, 1896).

She briefly visited Italy in 1897 and continued her education in Paris with James McNeill Whistler at the Academy Carmen. In attendance were four other women from the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, including Lucia Mathews.

- She traveled to Europe with Mabel Deming of Sacramento in order to study art (“Here and There in Society” 12). Both resided at the Girls’ Art Club and showed their work at the American Woman’s Art Association exhibitions at the Club. They also both studied at Whistler’s Academy. The other Hopkins Institute students training under Whistler were Marion Holden (Pope), and Caroline Rixford (Shields 277).

During her almost three years in Paris Lundborg received special attention for the large continuous mural that she painted with Alice Mumford at Henriettes’ Café. This work drew its title, The Queen of Hearts, from the Mother Goose rhyme and turned the café into a popular destination. The style of this work was heavily influenced by the English arts and crafts movement. Arthur Mathews said that Lundborg “has made more of a name for herself than any other woman from California in Paris because of her greater industry.”

- While living at 4 rue Chevreuse (like Mabel Deming and Belle McMurtry), Lundborg and so many other artists in the neighborhood were regulars at the small cremerie restaurant not far from the Girls' Art Club at 5 rue Léopold Robert. An April 4, 1920 article in the Baltimore Sun explained that she submitted the idea of painting the barren walls of the restaurant in exchange for food: “Why not turn our art into food? Let’s decorate the walls and for our pay – eat." She and her fellow artists decided to organize an anonymous drawing contest to determine who would be selected. Lundborg won the competition (San Francisco Chronicle, February 5, 1899, 22) with a drawing that featured a Queen of Hearts theme which seemed most fitting to the context. Lundborg enlisted the help of Alice Mumford, another Club resident, and in common accord with the owners, Mme Paulain and her daughter Henriette, they began frescoing the walls of the restaurant: So, with pencil, paint, and brush the girls set to their task and day by day the story made its way across the walls. Hard work it was, and tiresome too, and if ever artists earned their bread, it was those two girls who wielded their brushes from scaffold and stool. Eight long panels it required, panels in colors light and dark, with its word story told in painted, printed words along the top of the wall. At last it was completed, and the cheery room became more cheery for the colorful story of “The Queen of Hearts who made some tarts” had developed into a work of real art (Baltimore Sun, April 4, 1920).

- The colorful mural, complete with gold-leaf lettering and life-size figures extending over the four walls of the restaurant, was finished a year later. Mme Paulain staged a banquet in honor of the two artists, to which she invited 26 guests: And when Miss Lundberg returned to Paris, after a brief vacation, she found upon her arrival at the café table specially arranged for her. It was resplendent with bright, new silverware, the finest of white linens, and trailing roses, which, in Paris, represent a small fortune (San Francisco Chronicle, September 2, 1900).

- The same article in the San Francisco Chronicle remarked on the impact the frescoes had on the popularity of the restaurant: “People come in hordes from all over Paris and outside of Paris to view the unique decoration and the patronage of the place has been more than doubled." Years later, the new owner of the restaurant, a certain Monsieur Ribaut, wanted to restore the fading frescoes but only if the original artist could be found. He raised a hue and cry in the 1920 Baltimore Sun, but is it unclear if he found either of them: Lundborg did return to Europe in November 1920 and set up a studio in Paris with fellow Girls' Club artist and bookbinder Belle McMurtry.

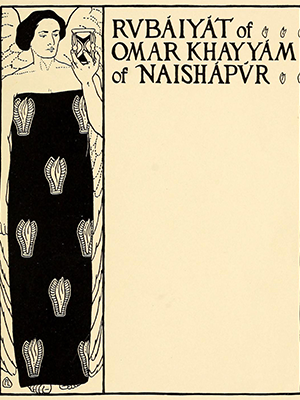

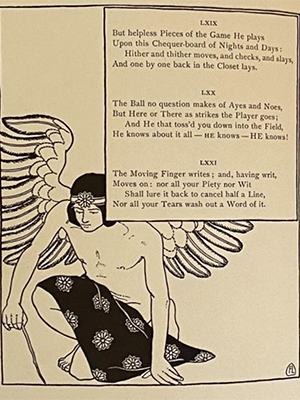

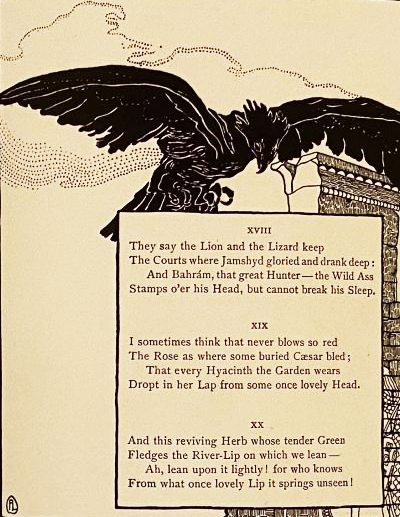

In the spring of 1900 she arrived in New York, where she was already known through her popular illustrations and the “distinguished” poster for San Francisco’s Lark magazine, to witness the publication by Godfrey Wieners and Company of her line drawings in a new edition of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat. Unfortunately, a reviewer for The New York Times found her work “very uneven” and “too much after the fashion of the Aubrey Beardsley school.”

- Lundborg had spent her final year in Paris illustrating Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat: The Astronomer Poet of Persia, published in 1900 by William Doxey in New York (San Francisco Chronicle, September 2, 1900) and including 41 full-page drawings and numerous caryatid borders. The deluxe version was issued in 250 numbered copies on Imperial Japan paper, bound in silk (Detroit Free Press, Sept. 10, 1900). The San Francisco Chronicle enthusiastically announced the forthcoming publication: Miss Florence Lundborg’s illustrations for the Rubaiyat, which is soon to be published by Doxey, have arrived. They are unique and interesting, each one distinct by itself and not one in the least like any previous illustration for the famous poem. There is a faint influence of Aubrey Beardsley traceable in Miss Lundborg’s present work. She is, however, strikingly original and bold in her decorative designs. Her lines are the most flowing and graceful” (June 4, 1899).

- However, when the publication was issued, the New York Times and New York Tribune thoroughly lambasted her illustrations: Of Miss Lundborg’s drawings, however, it is difficult to speak with approval. They are of the school of the late Aubrey Beardsley, but show nothing of the technical brilliancy which distinguished that curious figure in English art. Here and there is a page not badly decorated so far as the mere disposition of one is concerned, but Miss Lundborg shows very little sympathy with the text. There is nothing of Omar in her work […] Indeed, these imaginings of hers jar upon the reader, the spirit of them is so totally different from that of the poet. With the best will in the world to find merit in work over which the artist has, we suppose, labored with love and enthusiasm, we must confess our inability to see any reason why she should have meddled with Omar at all. Her publisher has given us a beautiful piece of bookmaking, but our pleasure in it is almost spoiled by the intrusion of the illustrations (New York Tribune, December 1, 1900).

On her return to San Francisco in early July she established a studio at 628 Montgomery Street. By the fall she was painting several panels; the first, entitled The Isle of Idleness, was based on an original motif. She continued to produce her lucrative “designs” for publications, including Rudyard Kipling’s Recessional. In the spring of 1901 she won the first prize in the poster competition at the California Club where she also displayed her Rubaiyat illustrations; that December she occupied the former studio of Mary Herrick Ross at 308 Post Street. The following year her drawings appeared in two other publications, The Easter Garden and I Am the Resurrection. By 1904 she was supplementing her income as an art teacher at Miss Head’s School in Berkeley, a posh private institution for girls. At this time she collaborated with Bertha H. Smith to produce “a book of six Indian tales” entitled Yosemite Legends. Florence executed the cover, marginal decorations and thirteen full-page half-tone illustrations in black, white and green. Lundborg finished several mural designs, including the walls of her brother’s East Bay home. She also contributed to the 1905 exhibition of the San Francisco Artists’ Society. In April of 1906 she suffered a “lamentable loss in the destruction of all her pictures,” primarily a mural and two dozen sketches at Vickery’s Gallery. Apparently, her studio on Montgomery Street was unharmed. She immediately stayed with friends and relations in Berkeley and Alameda. She also made a lengthy summer visit to Santa Barbara and possibly traveled to New York.

- A June 4, 1906 article bemoaned the loss of many works of art and studios of California artists which were destroyed in the Great San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906, including drawings by Matthews, numerous works at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, and the Sketch Club’s treasures, which had been housed in the California Club (San Francisco Chronicle 5).

In early September of 1906 she was appointed a “teacher in drawing and painting at Stanford University” with duties “to begin at once.” This appointment, however, ended after one year with her resignation and a renewed commitment to her own painting. Florence was invited to some of the pre-opening social events for the Inaugural Exhibition at Monterey’s Del Monte Art Gallery and unofficially advised its committees. Soon thereafter she was appointed to its jury of selection and “hanging committee.” In mid 1907 she established a small studio in San Francisco at 1716 Sacramento Street and returned to the East Bay as an art instructor at another private institution, the Ransom Marion School. During this period she received an important mural commission from Mrs. George H. Roe of Ross Valley to execute a frieze which used the San Francisco bay and wood nymphs as motifs. She also served on the jury of the Sketch Club. After 1908 there is no evidence that she either resided or taught in Berkeley. In April of 1909 Lundborg left her San Francisco residence for a two-year tour of western Europe in the company of the well-known artist and bookbinder, Miss Belle McMurtry. Florence resigned her position as a juror for the Del Monte Art Gallery. After visiting New York City the couple traveled in Spain and Italy where Miss Lundborg “made a special study of poster work.” Lundborg returned in August of 1911 to spend the summer at the family ranch in Los Gatos and by the late fall had a San Francisco residence at 1360 Jones Street and a studio initially at Jones and Washington Streets and then at 1367 Post Street; she maintained the latter into 1917. This studio adjoined the digs of Miss McMurtry. Florence registered on the local voter index first as a “Republican” and then as a “Democrat.”

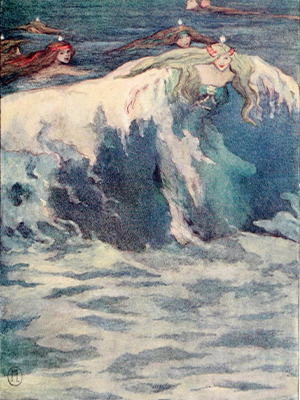

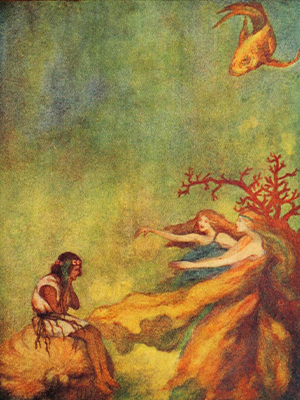

Early in 1912 she completed the illustrations for Mrs. John Lane’s translation of The Honey Bee by Anatole France.

- The translation by Mrs. John Lane was published in 1911 and Lundborg contributed 12 color illustrations, one of which was also featured on the book cover.

Lundborg’s copy of a Florentine fresco by Botticelli in the Louvre gained much favorable attention in San Francisco. For the home of a wealthy Portland patron she completed two mural panels each measuring three by fourteen feet, one depicting a “peacock amid masses of fruit” and the other showing a pheasant among garlands of grapes.

- In November 1913, she exhibited several of her paintings executed in Italy, Sicily, France, and California. The exhibit took place in her studio in the Studio building, 1367 Post Street (The San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1913, 35).

- In December 1913, she exhibited at the California Club-house at a show seen as “a basis for the display of artists by this state at the exposition of 1915” (Winchell 62).

In the spring of 1914 she contributed her Greek Theatre and Ionian Sea-Sicily to the Exhibition of Women Artists of California at Berkeley’s Hillside Club. Part of her exhibition history includes portraits, landscapes and still lifes at the: First Annual of the Berkeley Art Association in 1907, Arts and Crafts Exhibition in Oakland’s Idora Park in 1908, Vickery, Atkins & Torrey Gallery of San Francisco in 1906 and 1911, Sorosis Club of San Francisco in 1913, California Club of San Francisco in 1913, Senefelder Club in 1914 Inaugural Exhibition of the Oakland Art Gallery in 1916, Jury-free Summer Exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts in 1916, Traveling Exhibition of California Art in 1916-17, and SFAA between 1916 and1919; she was awarded a gold medal at the last venue. When the Sketch Club recreated itself in 1914 as The San Francisco Society of Artists, Miss Lundborg was elected its first vice president and to the board of the directors. She was widely regarded as one of California’s most important artists.

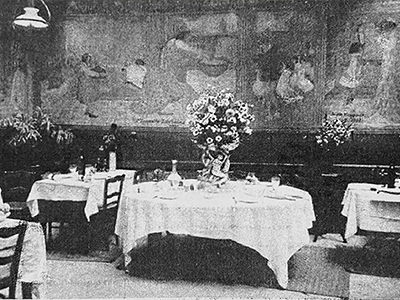

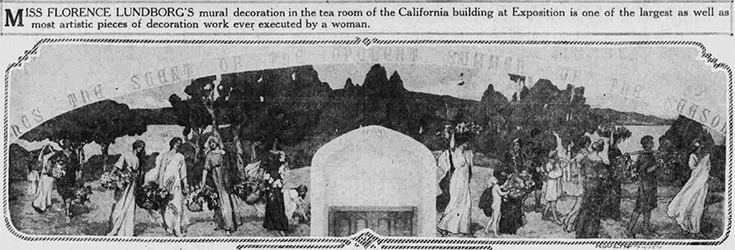

Florence received great attention and a bronze medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915 for her murals and oil paintings. The latter were described as “foreign scenes” – Etna in the Afterglow, Old Fountain-Taormina and Stone Pines – in contrast to her “series of California subjects for our own State building." Her triumph was the decorative mural in the tearoom of the California Building. It measured fifty-two by thirteen feet and offered an “heroic” scene “symbolical of the wealth of fruit and flowers… presenting a procession of figures moving with Arcadian joyousness through the landscape." This work included the citation from the Hellenistic poet Theocritus: “All breathes the scent of the opulent summer – of the season of fruits.”

- Florence Lundborg painted all the murals of the California Host Building at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (San Francisco Examiner, February 21, 1915). According to another San Francisco Examiner article covering exhibit installations: Workmen toiled all last night hanging the mural paintings of Florence Lundborg in the rest and ten rooms of the Woman Board in the California Host Building. Miss Lundborg herself remained until a late hour directing some of the finishing of the rooms, and to-day the tea tables are being installed, that everything may be ready for the informal reception of opening day. The largest of the murals arches a great space over the door in the north wall, the main entrance to the room. […] Reaching entirely across the room is an inscription above the painting” (February 17, 1915).

A typical example of her bright “decorative” work is the huge oil on canvas entitled The Hills Beyond the Garden. One of her displayed pieces at the 1916 Jury-free Summer Exhibition in the California Palace of Fine Arts was selected for a traveling show of California Art with stops at the museums and municipal art galleries in Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Boston, New York City and other eastern venues.

- In March 1916, she hosted a tea in her studio where she exhibited a “large oval-shaped panel showing a basket of California of flowers and fruit […] There is a gold background and the panel is edged with a conventional design in white on an old rose background. The panel will be framed in gold […]” (Winchell 19). It was commissioned by Mrs. William B. Storey, a former California resident who had moved to Chicago and wanted a souvenir of her native ground. The painting would adorn the wall above the fireplace of her living-room (San Francisco Examiner, March 21, 1916).

In the summer of 1917 she and her long-time companion, Belle McMurtry, permanently relocated to New York City and within a few years had a residence at 12 East Eighth Street.

- According to an article in the San Francisco Examiner, Florence and Belle traveled to New York City on June 15, 1917, where they planned to open a studio. The two had been friends for years, having lived at the Girls’ Art Club in Paris and shared a studio in San Francisco (Post Street). The same article announced Belle's marriage on September 27, 1923 to William Randolf Keltie Young, who would later become a Trustee of the San Francisco Public Library (October 6, 1923).

- Like many other artists, Lundborg put her skills to the service of war relief efforts. Although the following description is rather longwinded, the nature of her work, as well as that of other artists, is worth quoting at length: The work that Miss Lundborg is doing, for instance, does not require her presence in France or Belgium. She remains in her studio in New York, whither she and Miss Belle McMurtry went last summer to establish themselves. Miss Lundborg's forte is mural and expansive scapes. She is of great assistance to the war department, therefore, in the painting of huge canvasses which picture targets of cannon and machine guns and give gunners valuable view of terrain. The spirit in which art has come to the aid of the war has been commented upon by the government. Scores of artists have dropped all private work in order to devote themselves to preparing landscapes for shooting. They are splashing on "ten-league" canvasses, not with brushes of comet's tails, but with very large and substantial sheafs of bristles, reproducing scenes suggestive of "Somewhere in France." They use their own recollections of that fair land as they knew it when it smiled and they were art students. These canvasses are technically known as designation targets. They will be aimed at with unloaded guns while instructors in military science teach their students how to use their weapons so as to get full value of the ammunition used. Young artillerymen and rapid fire squads in the training camps could scarcely get an idea of the French terrain without these targets, and the instructors are able with their use to expedite teaching to an incalculable degree.The pictures are usually five feet high and nine in length. The artists paint lightly, using plenty of turpentine to keep the medium flowing and thin. They transcribe nature and the works of man, such as small villages, hayricks, bridges and other view to the canvas, now and then introducing the figure of a Boche [French referring to Germans] to give reality to the topography. The object of painting these landscapes is very definite. Thousands of the young men entering the national army from the cities have little idea of distances in the open country. One who is accustomed to gauging distances by city blocks is apt to have no "eye" for distances or ability to calculate distances Jn the open country. The average city-bred youth will go through the canyon-like streets after the manner of water in a sluice. He sees only a small distance ahead of him. Compared to him the youth brought up in the country has the vision of an eagle and the accuracy of sight of a sharpshooter. Alter a class has aimed at a haystack, a crumbling church, a clump of trees or a hillock in one of Florence Lundborg's pictures the student gunner finds that his idea of perspective is all wrong. Then the instructor steps in and he is shown just how to range his battery. The more the pictures are studied by the student unfamiliar with the wiles of nature the more useful do they become and more competent does the gunner become. Artillery officers are continually asking for more of the pictures. The value of sculpture to the same branch of the service is obvious. Bas-reliefs and lay figures play a large part in the target practice. The war department is much pleased with the work the artists have been doing and has made photographs of many of the canvasses for distribution (San Francisco Examiner, April 28, 1918).

- One of Lundborg’s paintings was exhibited at the Book and Flower Mart on Fifth Avenue, with an army officer present to explain the utility of such works for field training (New-York Tribune, April 1, 1918).

Lundborg did not abandon California completely and in May of 1918 contributed to the opening exhibition of the Spreckels Art Museum, the precursor to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. In the late summer of that year she exhibited “a fine flower piece” at the Palace of Fine Arts. She joined Colin Campbell Cooper and other artists in the war effort and painted massive landscapes to aid in the training of gunners for the U.S. Army. She also catered to civilian tastes by publishing her drawings in the third issue of the art journal Playboy. In January of 1919 Willard Huntington Wright, the demanding critic at the San Francisco Bulletin, praised her still life at the Loan Exhibition in the Palace of Fine Arts as a “brilliant color product;” a year later in May her Berkeley study entitled California Oaks at the National Association of Women Painters’ Exhibition won special praise from the critics. On her application for a third passport she was described as five feet seven inches tall with gray eyes, gray hair and “normal” features.

In October of 1920 she sailed on the S.S. Adriatic to Europe with Miss McMurtry and established a studio in Paris. On her return to New York City Lundborg executed murals for Wadleigh High School and Curtis High School on Staten Island.

- In Paris, Lundborg and McMurtry were located at 49 bd. du Montparnasse (New York Herald Paris edition, December 19, 1920, 2).

- In 1924, Lundborg won the commission to paint a mural for Wadleigh High School in Manhattan; 12 artists had entered the competition (San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1924, S5). At the time, Wadleigh located at 215 West 114 Street in Harlem, was an all-women’s school. According to the Bulletin of High Points in the Work of the High Schools of New York City, the mural decorating the front wall of the auditorium depicted the ideals of the school: This picture, “The Garden of Inspiration,” shows students at work and play. Some are sitting at the feet of instructors, others carrying on discussions in groups, and still others are following individual paths. Quietly, joyously, they learn from tree and flower, from music, science, literature, and art the lessons that will enrich their lives. At either end of the decoration is the phoenix, that mythical bird which inspires the others through its sacrifice, and thus regains youth and joy. Looking toward those who have not yet entered the garden, the phoenix offers an invitation. Next to them are young girls just entered, eager and expectant. Behind each child is her guardian, quietly impelling her towards the new influences. The landscape is symbolic of many things that youth must experience; the trialware suggested by the cactus trees, the peace of knowledge by the olive, youth and grace by the fruit trees and the white birches, strength by the sturdy trunks and foliage of oak and maple. In the center of the painting, gathered around a pool where the lotus, the flower of life, is blooming, are seven modern muses from whom the students derive knowledge and wisdom. These are Creative Invention, whose alert movement reveals the activity of her mind; Universal History, lifting up a crystal globe; Horticulture with a basket of the fruits of the earth; Literature with her scroll; Music with pipes, and Art with brushes and palette. Two small children, more newly come to the earth experience and so more aware of the eternal, are offering branches of laurel. Overall the Spirit of Inspiration stretches her golden wings, filling the garden with her bright presence. In the background are mountains and a golden lake. Even the colors – blue, soft green, violet and vibrant rose, with the radiance of the dominating yellows and gold – show that more is meant than meets the eyes. According to the legend across the top of the painting, this is “The Garden of Inspiration, where Muses haunt clere spring or shadie grove or sunnie hill.” The picture suggests happiness, progress, nobility of character, and the beauty of life. These are the aims and spirit of the Wadleigh High School (42-43).

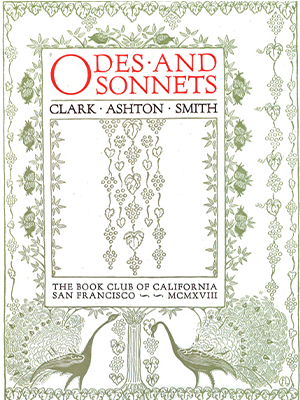

Throughout her life she received many commissions to illustrate magazines and books. She contributed the art work to Clark Ashton Smith’s Odes and Sonnets in 1918. She also sold prints from her own woodcuts. During a visit to California in 1927 she was given a reception by the members of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists. Miss Lundborg died in New York City on January 18, 1949.

- Her apartment at the time was in the Roger Williams Hotel, 28 East Thirty-first Street. She died in her sleep at the age of 78.

Sources for the images and bulleted information

- “Art.” New-York Tribune, April 1, 1918, p. 11. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Art Note.” The San Francisco Chronicle, September 8, 1901, p. 9. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Bowl of Color.” Lenox Hill Hospital.

- Bulletin of High Points in the Work of the High Schools of New York City, vol. 11, no. 9, November 1929, pp. 42-43. HathiTrust.

- Cholly, Francisco. “Among the Swells and Belles.” The San Francisco Examiner, August 9, 1909, p. 5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Cholly, Francisco, “S.F. Artist Becomes Bride in New York.” The San Francisco Examiner, October 6, 1923, p. 9. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Crombie, John. Montparnasse à la carte. Paris: Kickshaws, 2005.

- Curtis High School, lobby murals.

- Edwards, Robert W. Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, vol. 1, East Bay Heritage Project, Oakland, 2012. An online facsimile of the entire text of vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website as "Archived copy." Archived from the original on April 29, 2016.

- “Exhibits Reflect Glories of All Nations: “Hang Beautiful Murals in Woman’s Board Room.” The San Francisco Examiner, February 17, 1915, p. 6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Fame for an American Girl. Age-Herald, February 19, 1899, p. 24. Readex.

- “Florence Lundborg.” The New York Times, January 19, 1949, p. 27. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- France, Anatole. The Honey-Bee, translated by Mrs. John Lane. John Lane Company, 1911. Internet Archive.

- "Henrietta's Queen Of Hearts Needs Restoring." The Baltimore Sun, April 4, 1920, p. A14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Here and There in Society.” The San Francisco Examiner, Aug 12, 1897, p. 12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Khayyam, Omar. Rubaiyat: The Astronomer Poet of Persia, William Doxey, New York, 1900.

- Knickerbocker, Cholly. “Pretty Vassar Graduate to be the Bride of a San Franciscan.” The San Francisco Examiner, June 11, 1900, p. 6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Latest Books.” New York Times, December 8, 1900, p. BR48. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Legends.” The Baltimore Sun, December 7, 1904, p. 8. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Limelight thrown on San Francisco: Sketch Club Opens its Show To-Day.” The San Francisco Examiner, November 16, 1913, p. 35. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Literary." Detroit Free Press, September 10, 1900, p. 4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Living Posters." San Francisco Chronicle, September 19, 1896, p. 8. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Many Going to Europe.” Los Angeles Times, November 8, 1920, p. II5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Nadan, Tal. “Edith Magonigle and the Art War Relief.” Blog. New York Public Library.

- National Archives Catalog.

- News of Americans Day by Day.” The New York Herald Paris edition, December 19, 1920, p. 2. Gallica.

- “Notes of the Studio.” San Francisco Chronicle, June 4, 1906, p. 5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Omar: An Illustrator's Incongruous Accompaniment to the Quatrains." New-York Tribune, Dec 1, 1900, p. 10. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Painted Landscapes as Range Finders for Guns.” New York Times, April 14, 1918, p. XX1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Parker, Alice Lee and Milton Kaplan. “Prints and Photographs.” Quarterly Journal of Current Acquisitions, vol. 18, no. 1, November 1960, pp. 40-52. JSTOR.

- “1916, Exhibit, Fine Arts Palace.” San Francisco Examiner, June 18, 1916, p. 4N. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Phelan Medal for Modeling.” The San Francisco Examiner, May 21, 1896, p. 13. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Targets are Painted by Art Colony.” The San Francisco Examiner, April 28, 1918, p. N5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “S.F. Girl Wins Art Honors in the East.” The San Francisco Examiner. November 16, 1924, p. S5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "S.F. Woman Triumphs in Work of Art." The San Francisco Examiner, April 25, 1915, p. 38. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “San Mateo Home Luncheon Assembles Coterie to Wish Girls Safe Journey.” San Francisco Chronicle, June 3, 1917, p. 16. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Sewer, Jaquelyn Days. “The American Artistic Poster of the 1890s.” PhD Dissertation, City University of New York, 1980. ProQuest.

- Shields, Scott, A. “Legends of Bohemia: The Monterey Peninsula and its early art colony, 1875–1907.” PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas, 2004. ProQuest.

- Smith, Clark Ashton. Odes and sonnets. Book Club of California, 1918. HathiTrust.

- Starr, Kevin. “The Wonderful year of 1896.” The San Francisco Examiner, April 10, 1980, p. 26. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Studio Notes.” The San Francisco Chronicle, February 5, 1899, p. 22. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Studio Notes." San Francisco Chronicle, June 4, 1899, p. 22. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Studio Tea is Treat for Smart Set.” The San Francisco Examiner, March 21, 1916, p. 11. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “The Johnson Dinner Party.” The San Francisco Examiner, July 31, 1900, p. 10. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- The Lark Covers. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- The Lark Paintings and Woodcuts. Artnet.

- The Lark. Detroit Institute of Arts.

- The Lark. Biblio.com.

- The Official History of the California Mid-Winter International Exposition, Press of the H.S. Crocker Company, 1894, p. 123. Gallica.

- “The Parisian Cafe Decorated.” The San Francisco Chronicle, September 2, 1900, p. 26. Newspapers.com.

- “Triumph of Modern Women’s Work and Influence Revealed in Expositions Purpose and Achievement.” The San Francisco Examiner, February 21, 1915, p. 32. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Verdenal, D.F. “Rose Cliff Loses its Pretty Name.” The San Francisco Examiner, August 5, 1900, p. 16. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Wart Notes.” San Francisco Chronicle, April 15, 1906, p. 50. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Winchell, Anna Cora. “Artists and their Work.” San Francisco Chronicle, March 12, 1916, p. 19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Winchell, Anna Cora. “Club Exhibit Draws Big Crowds: Rooms Thronged by Art Lovers.” The San Francisco Chronicle, December 14, 1913, p. 62. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Women’s Board Opens Tea Room.” The San Francisco Examiner, February 23, 1915, p. 3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.