Janet Scudder, 1869 – 1940

Renowned American sculptor Janet Scudder was born Netta Deweze Frazee Scudder on October 27, 1873 in Terre Haute, Indiana to Mary and William Scudder. Unlike many of her peers who also studied in France, Scudder did not come from wealth; rather, hers is a rags to riches story in which serendipity combined with talent led to a successful career in the United States and in Europe.When she first came to Paris, Scudder did not live at the Girls' Art Club, which did not have available rooms. Later, she and her friend Zulime Taft managed to find a room at the Club.

As a young artist, she lived at the Girls’ Art Club, exhibited her work at several AWAA shows, and remained close to many artists whom she met during her early years in Paris and Giverny. Scudder recalled with fondness living at 4 rue de Chevreuse from 1894-1896 in her autobiography, Modeling My Life:

I have always felt a personal gratitude to Mrs. Whitelaw Reid for having started that Girls’ Club [...] It was a delightful old house in the Rue de Chevreuse, under the direction of a charming French lady who took a personal interest in the young women there and mothered each one of us individually. The students who lived in the house represented every branch of art - painting, sculpture, music and architecture; and just the mere fact of living there, surrounded by so many of them, all working with enthusiasm, was tremendously stimulating. We were made extremely comfortable, had the privilege of using the large library and were often entertained with musical parties and exhibitions got up by the more advanced students; but best of all was the fact that the expense was so little that even I was able to live there until I left Paris (111-112).

Before she arrived in Paris to pursue her artistic training in earnest, Scudder endured a difficult childhood (the death of her mother and several siblings). She enjoyed art from a young age and took Saturday drawing classes in Terre Haute. After graduating from high school in 1887, Scudder enrolled at the Cincinnati Art Academy and changed her name to Janet. While in Cincinnati, she studied sculpture, woodcarving, painting, and the decorative arts, but her family’s financial difficulties forced her to come home. She taught woodcarving to make ends meet in Indiana but was able to return to Cincinnati in 1890 to complete her training, thanks to her oldest brother’s financial support.

After Cincinnati, Janet moved in with her brother's family in Chicago in order to study at the Art Institute. She worked as an assistant for sculptor Lorado Taft, helping create monumental sculptures for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Scudder and Taft’s other female assistants were nicknamed the White Rabbits for their collective ability to swiftly ascend the many ladders required to produce large-scale sculptures- several future Girls’ Art Club affiliates were among this group.

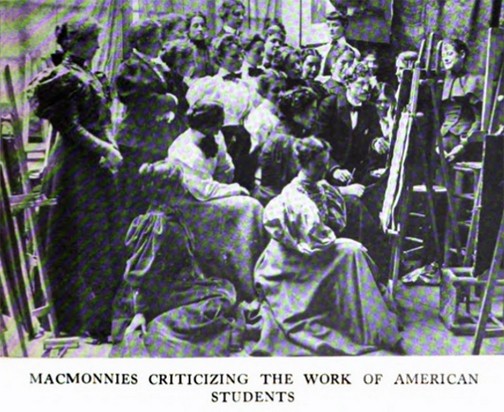

Scudder traveled to Paris with Zulime Taft, sister of Lorado, in 1894. She enrolled in classes at the Académie Colarossi before transferring to the Académie Vitti, where Frederick MacMonnies was running a highly popular women-only sculpture course (Crombie 50). Scudder had seen MacMonnies' fountain, "The Barge of State," at the Columbian Exposition and was determined to study with him in France. She succeeded in convincing him to hire her as an assistant and, at the age of twenty-five, Scudder became the first woman to work in his atelier.

After a few years of living at the Club, Scudder returned to the United States in 1896 and worked in New York for a short time, including a failed stint in the studio of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. She completed a commission (the seal of the New York Bar Association) facilitated by Silas B. Brownell, the father of her artist friend Matilda whom she had met at Colarossi (Dearinger 438). She exhibited the seal at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. During this time in New York, she also honed her abilities as a sculptor, becoming particularly adept at bas-relief portraits.

Janet wrote a delightfully informative article on American art students in Paris for Metropolitan Magazine in April 1897. In addition to describing the importance of art students arriving in Paris with enough money to live for the whole year ($500 for one year, $1,000 for two years), she also tells us that the kitchen at 4 rue de Chevreuse was visible to the public and "the cook, a good old peasant with sabots, is ever busied with shining pots and pans" (241). And she also shared what her art training entailed: “Part of the routine of an art student is to attend a life class in the morning. As I was studying sculpture I modelled in the afternoon, and in the evening I assisted at the evening drawing class. One requires great physical strength to work the entire day, and it is hardly advisable” (242).

Aided financially by Silas Brownell, Scudder returned to Paris in 1898 with Matilda (and the family's French maid) to study at the Académie Colarossi. They did not take up residence at 4 rue de Chevreuse but shared a small home at 253 boulevard Raspail for three years. Scudder identifies those three years as "the most important in my career as an artist. It was during that time that I found myself" (Modeling My Life 151). MacMonnies would visit her studio regularly and he even succeeded in selling several of her medallions to the Musée du Luxembourg. Her first Salon appearance came in 1899 at the Salon des artistes français, where she exhibited a plaster bas-relief portrait in the sculpture section and a bronze medallion in the decorative arts section. She was also among the women artists invited to represent the United States at the 1900 Exposition Universelle held at the Grand Palais; she showed a decorative panel for a music room that was highly acclaimed. Scudder would continue to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salons in 1900, 1901, 1902, 1905, 1908, 1910, 1911, 1912, 1913, and 1914.

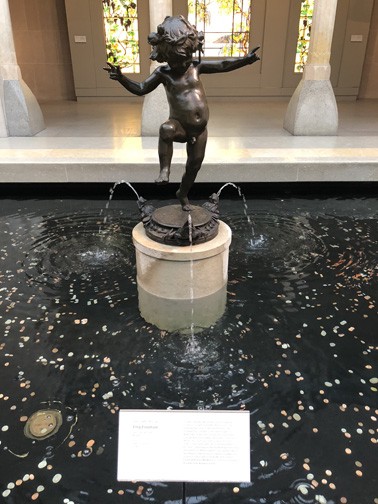

After spending the winter of 1899-1900 in Italy, Scudder was inspired by the ornamental fountains and Renaissance sculptures she had seen, particularly the works of Donatello and Verrocchio. She continued working on bas-relief portrait medallions until she experienced a moment of sudden and great revelation: a young boy model rang her doorbell out of the blue and asked to pose for her. Urged by her maid to relinquish working on portraits of "dead people," she let him enter:

[…] and we undressed the little boy. Then, quite nude, he grabbed the sandwich which Parot had thrust into his hand and began dancing about, chuckling delightedly to himself all the time. In that moment a finished work flashed before me. I saw a little boy dancing, laughing, chuckling all to himself while a spray of water dashed over him. The idea of my Frog Fountain was born (Modeling My Life 171).

Scudder returned to New York in 1901 after having a bronze model of "Frog Fountain" cast at a foundry in Paris. She was firmly convinced that she could design fountains for gardens, terraces, and courtyards that would appeal to a wealthy clientele. A series of chance encounters brought her into contact with the beaux-arts architect Stanford White, who ultimately commissioned four "Frog Fountains," including one for his own Long Island estate, Box Hill. A fifth can be seen today in The Metropolitan Museum of Art's American Wing. The Met's cast was commissioned at the recommendation of trustee Daniel Chester French and was purchased by the museum in 1906 (Dimmick and Hassler 526).

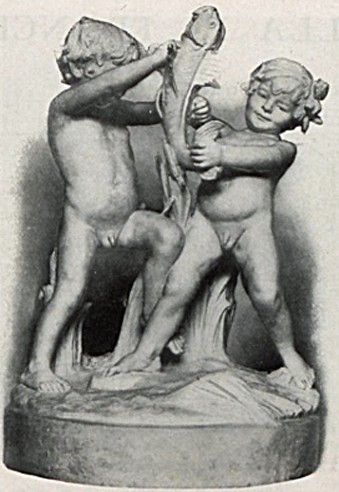

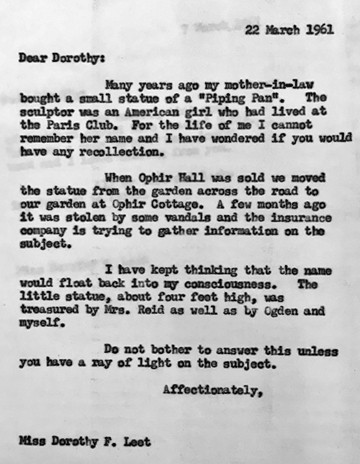

Scudder's fountains and sculptures often featured children at play, whom she described as her "water babies." The fountains appealed to rich Americans (including business mogul John D. Rockefeller and railroad magnate Henry E. Huntington) who installed these happy works in their manicured gardens. Throughout her career, Scudder received at least 30 fountain commissions, many of which were incorporated by White into his architectural projects (Dimmick and Hassler 525). Elisabeth Mills Reid, who became Scudder's friend, acquired her bronze "Piping Pan" (also called "Young Pan," which was stolen many years later from the family property, by then owned by Helen Rogers Reid).

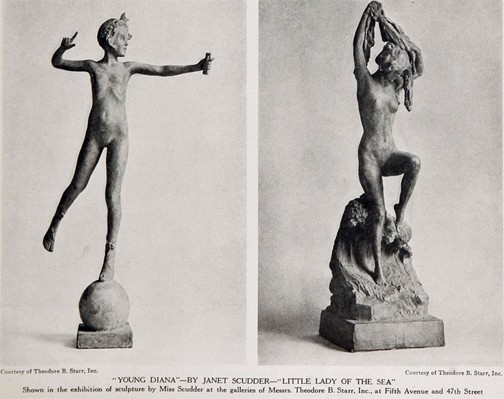

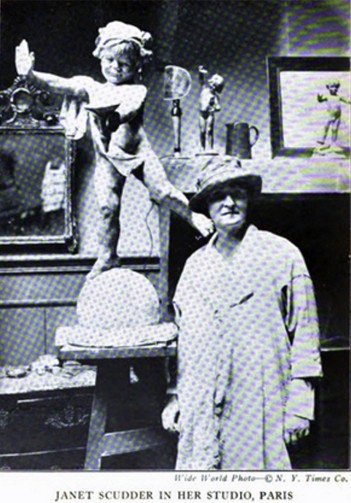

Having returned to France around 1908, Scudder rented a small house at 1 rue de la Grande Chaumière (replaced today by a modern apartment building) where she spent the most "profitable and interesting years" of her career (Modeling My Life 233) and received innumerable guests: Mrs. Stanford White; historian Henry Adams; writer Gertrude Stein; writer Teddy Bean; scenic designer Gordon Craig; Mme Maeterlinck, the soprano Georgette Le Blanc; patron of the arts Mabel Dodge; journalist Mildred Aldrich; and Ambassador Robert Bacon. She also befriended the French sculptor Jeanne Poupelet, whose work she successfully introduced in the U.S. Another well-regarded sculptor, Malvina Hoffman, worked as Scudder's studio assistant, helping her execute "Young Diana," which was completed in 1910 and shown at the American Pavilion of the Rome Exposition that year. In 1911, the sculpture won an honorable mention at the Paris Salon.

Her studio and residence were situated around the corner from the Girls' Art Club during one of its major periods of renovation, when a new residential building was added to the property in 1911-1912. Scudder humorously describes the construction's effect on the neighborhood, though she mistakenly attributes it to the building of St. Luke's Chapel (which had been erected way back in 1892):

[...] an old stable in the street was pulled down to make room for the "tin" church which was being built just behind the Girls' Club. With the destruction of the stable, an army of rats were cast out upon the world. Of course they had to find other quarters and with one accord they decided upon my house. My love of animals has never carried me to the extent of cultivating rats; and when they descended upon me the largest I have ever seen, quite as big as my dog I knew that something had to be done. In connection with this alarming situation was the fact that my lease was about up. The outcome of the episode was that I decided I wanted a house in the country near Paris (Modeling My Life 245).

Scudder left rue de la Grande Chaumière and bought a house on June 13, 1913 in Ville d'Avray (19 rue de Sèvres), which she maintained until she left France permanently in 1939. She maintained a Paris studio at 70bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs.

Scudder had just bought her villa when the onset of WWI forced her to return to the U.S. In New York, she engaged in French war relief efforts, raising people's consciousness and garnering donations. She was also one of the four women who organized the Lafayette Fund and the "Pour les écrivains français" fund for French writers. She lent her Ville d'Avray home to the YMCA, whose designated role in WWI was

[...] to provide amusement and moral welfare to the soldiers [...] in 'huts' or 'canteens' on or near the war front. These 'canteens' took the form of a tent, hole in the ground, or a small building. These buildings were turned into clubs, theaters, gyms, post offices, or perhaps a general store for the soldiers. The women often served coffee, doughnuts, and gave out books to the soldiers to read [...] (National Heritage Museum).

Her home became just that, a canteen used by French and, later, American soldiers.

While in New York, she completed a number of sculptural commissions and was able to return to France in 1915. Eventually, she and her singer friend Mrs. Lane were appointed by the National War Work Council of the YMCA as entertainers for wounded soldiers, touring France from camp to camp. Lane sang and Scudder worked as her manager. When Lane's voice gave out, they volunteered as "hut" decorators in various soldier camps. In 1918, they were transferred to the Red Cross and continued their decoration tour. Scudder also rented her studio at 70bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs to the American Red Cross, which had already established a military hospital at 4 rue de Chevreuse. In Scudder's Paris studio, Anna Ladd and Jeanne Poupelet fashioned portrait masks to aid wounded and disfigured soldiers through 1919.

Like many of her Girls' Art Club/AWAA peers, Scudder passionately supported women’s suffrage and she participated in the 1915 "Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by Women Artists for the Benefit of the Women's Suffrage Campaign" in New York. This is where her old friend Elisabeth Mills Reid purchased Scudder's sculpture "Young Pan" (not listed in the exhibition catalogue) on the very first day (Dennison 2003, 27). Scudder advocated for exhibitions to include both male and female artists, critiquing the common practice of holding separate exhibitions for the sexes. She longed for a time when artists would not be described by their sex or gender but purely by their artistic accomplishments. She even wore pants while working in her studio, an astonishingly bold act for a woman in the early twentieth century that was highlighted in a 1912 Vogue article about American women artists in the Paris Salons: “As she descended from her ladder to greet me, she apologized laughingly for the absence of a skirt in her attire, declaring that experience had taught her the uselessness of such a garment in her profession. …[She] now wears a trim costume which, with her unworn face, slender figure, long step, and swinging gait, makes her more than ever resemble a boy” (Friend 24).

For most of her life Scudder would split her time between Paris and New York. She regularly returned to 4 rue de Chevreuse, where she frequently participated in the American Woman's Art Association (AWAA) exhibits. Though the reviews only mention her submissions to the 1905 and 1912 AWAA shows, it is worth noting that the 1912 exhibition at the Club was meant to showcase stars of the contemporary art world (Sargent, Rodin, Whistler, etc.) and Scudder was one of only three women (along with Elizabeth Nourse and Florence Esté) whose work was included. In the 1930s, she attended teas, Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners (with Gertrude Stein as her guest in 1931), as well as other official functions at the Club. Scudder was a guest at the Legion of Honor award ceremony for Dorothy Leet in 1934 and was among the speakers at Leet's farewell dinner in 1938.

When WWII began in 1939, Scudder worked to aid refugee children in France before her failing health forced her to return to the United States permanently with her companion, suffragist, lawyer, and children's book author Marion Cothren. They settled in New York and summered in Old Lyme, Connecticut and Rockport, Massachusetts. Janet Scudder died of pneumonia in Rockport in June 1940 at the age of 66.

Many of Scudder's works grace major museum collections and private or public spaces around the world. She was the first American woman sculptor whose works were acquired by the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris.

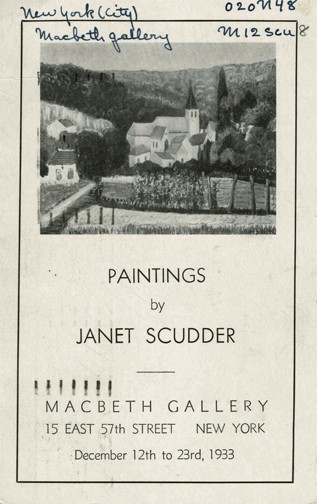

In addition to winning a bronze medal at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, she was awarded a bronze medal for a sundial in bronze, which she exhibited at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and an honorable mention at the 1911 Paris Salon. Ten of her sculptures and garden fountains were exhibited at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, for which she received a silver medal in recognition of merit. In the 1930s, she took up painting,exhibiting her canvases at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City in 1933 (she had already exhibited sculptures there in 1908).

Scudder was a member of the National Sculptors Society and was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1920. She was also a member of the art committee of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and was among the founders of the Women's City Club of New York (along with Helen Rogers Reid). For her support during WWI, she was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1925, the same year that she published her autobiography, Modeling My Life. Her obituary in The New York Times quoted her describing her vocation:

I became a sculptor because I couldn’t help it. I tried water-colors, wood-carving, portrait-painting, and I hammered brass. Brass gave me no response, and every echo was a thud (June 11, 1940, 25).

Sources

- Dearinger, David Bernard. Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925. Hudson Hills, 2004.

- Dennison, Mariea Caudill: “Babies for Suffrage: The Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by Women Artists for the Benefit of the Woman Suffrage Campaign,” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 24, no. 2, Fall 2003, pp. 24–30. JSTOR.

- Dimmick, Lauretta and Donna J. Hassler. American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born between 1865 and 1885. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999.

- Dimmick, Lauretta. "The Fountainhead: The Genesis of American Garden Sculpture." Traditional Fine Arts Organization, 2009.

- Friend, Margaret Alice. “American Women in the French Salons.” Vogue, vol. 40, no. 2, July 15, 1912, pp. 24-5, 52. ProQuest.

- Lublin, C. Owen. “Through the Galleries.” Town & Country New York, vol. 68, no. 3524, November 29, 1913, p. 23, 28. ProQuest.

- MacBeth Gallery exhibit announcement, 1933. Metropolitan Museum of Art Digital Collections.

- McCarthy, Laurette E. "Janet Scudder." Spellman Gallery.

- Mechlin, Leila. “Janet Scudder-Sculptor.” The International Studio, vol. 39, nuo. 156, February 1910, p. LXXXI-LXXXVIII. Google Books.

- National Heritage Museum, 2009.

- Pan American Exposition (Buffalo 1901).

- Scudder, Janet. “The Art Student in Paris.” Metropolitan Magazine, vol. 5, no. 3, April 1897, pp. 239-244. Google Books.

- Scudder, Janet. Modeling My Life. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1925. Internet Archive.

- Special to the New York Times. “Janet Scudder, Sculptor, Dies, 66.” The New York Times, June 11, 1940, p. 25

- “Two of the Foremost American Sculptors.” Harper's Bazaar, vol. 52, no. 10, October 1917, p. 56. ProQuest.