The University Club's History

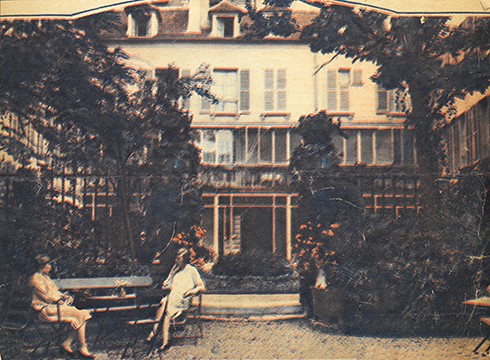

The trees in the garden form a green retreat. Grace and quiet are in this house (Howard 12).

The American University Women's Club ushered in a new era for 4 rue de Chevreuse, one that would link the property to an international network of women dedicated to education and research. In many respects, it laid the foundation for the property's future iterations as a center dedicated to French – American collaboration in the realms of higher education and cultural exchanges. Its very existence and modus operandi were fashioned by a determined set of women who were willing, and able, to extend their vision beyond borders.

Transformation

Plans for the future of 4 rue de Chevreuse were already underway in early 1919. Alice Parsons visited Paris and met with Roselle Lathrop Shields, the last director of the Girls' Art Club who had stayed on-site to work with American Red Cross personnel during the war. Before Parson's departure, Dean Gildersleeve of Barnard College outlined nascent plans for transforming the property into a university women's club:

The Paris centre might, it seems to me, begin on a small scale as a headquarters for information and sociability for university women, especially students. It should not, I think, be primarily concerned with supplying a place of residence, though it might do this in a small way incidentally. Its aim should be chiefly to bring the University women in touch with one another and with characteristic phases of French life and thought. It would be unfortunate to have it confined to American college women alone. It might begin as an Anglo-American center and later take in women of other nationalities. It could largely be supported by a membership fee, but would undoubtedly need some contributions to finance it at the beginning (Letter to Alice Parsons, February 10, 1919).

On September 2, 1920, Bryn Mawr President M. Carey Thomas, chair of a committee of college and university women on clubhouses abroad, wrote to Reid asking her to hold off on renting her property until the committee could make a proper offer. On September 18 that same year, Gildersleeve wrote to Reid describing the committee's plans for establishing such a clubhouse at 4 rue de Chevreuse "which will permit educational intercourse between the university women of different countries. The proposal for a Paris headquarters, where so many American women will now wish to study, is by far the most important one" (Letter to Reid, September 18, 1920).

Caroline Niemczyck reiterated the importance of establishing this club in her allocution at the Centennial celebration of Reid Hall in 1993:

These women approached Elisabeth Reid to see if she would let them use [the space] as a residence and meeting place for their members, all of whom were community leaders, academics, or professional women, all college-educated and aware of their new powers as independent women. They hoped meetings among women from different nations would foster international understanding and serve as a building block for world peace [...] (9).

In response to the committee's proposal, Reid made clear that she did not want her property to become a mere boarding house, that priority should be given to American women, and that women artists should still be accepted as residents. Reid also wanted to establish a medical clinic on the premises to "care for the surrounding neighborhood" (1921 draft letter to Gildersleeve). In her reply, Gildersleeve insisted that while the club would be wholly run by Americans, it would be vital to reserve rooms for women of other nationalities, especially the French, and to create cultural programs through which residents could meet their peers from other countries (February 21, 1921).

Although Reid ultimately approved this ambitious project, the property was not immediately available: the American Red Cross (ARC) asked to extend its residency at 4 rue de Chevreuse for three more years. All ARC personnel finally moved out in March 1922; however, eight years of war and Red Cross operations had left their mark on the buildings and gardens. Reid generously paid for various repairs to ready the property for future use. In her memoir, Many a Good Crusade, Gildersleeve described the exacting efforts undertaken to refurbish the site: "Mrs. Reid had the buildings repaired and decorated. She even provided flowers to adorn the rooms, and a caterer who served excellent food" (140).

It was thus only on June 1, 1922 that 4 rue de Chevreuse was officially loaned to the group of visionaries who so keenly wished to develop an international headquarters for university women in Paris. They were Virginia Gildersleeve (Dean, Barnard College); M. Carey Thomas (by then former president of Bryn Mawr); Blanche Ferry Hooker (Vassar alumna); Dora Emerson Wheeler (Wellesley alumna); Helen Rogers Reid (Barnard alumna and Reid's daughter-in-law); and Alice Lord Parsons (Smith alumna). The terms of the loan guaranteed use of the property for five years.

Joyce Goodman's essays, Paris Club House Emerging, Reassuring Elisabeth Mills Reid, and A Potential Site in Paris, all provide additional details.

The University Women's Club is born

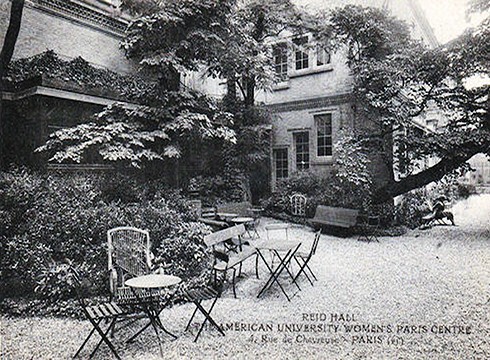

The American University Women’s Paris Club would serve as the clubhouse and headquarters in Europe for the International Federation of University Women (IFUW). The Club officially opened on July 14, 1922. An article in the New York Tribune marked its opening and announced that: "The organization will attempt to help all American women students in Paris, and there will be a free dispensary service" (July 16, 1922, 10). The IFUW held its first conference at the Sorbonne in July and celebrated the opening of the Club on the rue de Chevreuse. Over 350 people attended the conference: 50 Americans and 300 participants from 18 other countries. Discussions focused on the social role of university women in France; married women and liberal professions; French women artists; establishing student and faculty exchanges; raising funds for travel stipends; and actions for world peace. According to Joyce Goodman:

On the surface the IFUW conference ran brilliantly but Elizabeth Reid's daughter in law, Mrs Ogden Reid, who arrived in Paris in advance of the conference, had to step in at the last minute to bale [sic] out the conference arrangements both practically and financially. This led to the decision to appoint [a manager of the Club] as well as to establish a house committee chaired by the UK-based American Alys Russell (Bertrand Russell's first wife and Carey Thomas' cousin). As chair of the house committee Alys agreed to travel monthly from the UK to Paris to report on Reid Hall to the Board of Managers in the USA and appears to have done so but in 1925 she was diagnosed with cancer for a second time and had radiological treatment and was out of action convalescing for longer than she had anticipated (personal communication, May 2020).

In 1923, the French chapter of the International Federation, the Association des Femmes Françaises Diplomées des Universités (AFDU), established its headquarters at 4 rue de Chevreuse with Marie Octave Monod as its leader. The Société Féminine Nationale de Rapprochement Universitaire was also headquartered on-site in 1923. The goals of these organizations were to promote international intellectual cooperation among women, and to provide fellowships that would enable women to complete their dissertations, pursue specific research interests, or hold teaching positions in Paris.

For the IFUW, the Paris headquarters was part of a network of clubhouses that served as "centers of international acquaintance and hospitality" (Bulletin of the Associate Alumnae of Barnard College, December 1924, 9). In the 1920s, these clubs were located in Washington, New York, Paris, London (Crosby Hall), Athens, and Rome.

Leadership

During its first few years, the University Women's Club was managed by Louisa K. Fast (1878 – 1979), a Smith College graduate from the class of 1898. After graduating from college, Fast returned home to Tiffin, Ohio and became a librarian (Joyce Goodman, personal communication, 2020). During WWI, she assisted in organizing donated books into a library at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio (1917). The U.S. government paid for her passage to Paris as part of the Smith College Relief Unit in 1919, where she volunteered at the Military Library, open to French students. At the end of the war, the Military Library was disbanded, the books were redistributed, and Fast returned to Tiffin.

She sailed back to Paris in 1922 to manage the University Women's Club. Minutes from the Club's board meeting indicate that Fast "took charge" on September 6 of that same year (October 18, 1922).

Under her leadership, the Club counted nearly 1,000 members by 1926. These members represented 64 colleges and universities, 36 American states, and four other countries. U.S. Immigration records show that Fast traveled from Paris to the U.S. in the summer of 1923 and the summer of 1925 – presumably a biennial arrangement that was part of her employment contract.

Fast's leadership was called into question when Elisabeth Mills Reid visited 4 rue de Chevreuse in 1926 and was appalled by the condition of the premises; she warned the Club's board that she would sell the property if the situation did not rapidly improve. In her letter to Gildersleeve, Reid held Fast responsible for deferring crucial maintenance issues: "Miss Fast is a nice woman, but her ideas on economy seem to me a little exaggerated" (June 1, 1926). In the same letter, Reid expressed her disappointment with the residents at the Club, who seemed to her more interested in travel and pleasure than in education: "I asked Miss Fast how many, in four years, had amounted to anything, or had anything to show for their work abroad, and she had great difficulty in mentioning four."

In her June 17 response to Reid's concerns, Gildersleeve defended the Club's role in the world of education by forwarding a June 12, 1926 letter from President William A. Neilson of Smith College in which he lauded Miss Fast and her staff for creating a welcoming atmosphere, organizing many thoughtful activities, and providing the information necessary for American women to comfortably navigate life in Paris. Gildersleeve also reminded Reid that it was difficult for students "[...] to show much definite result by attaining academic distinction until a good many years have passed. In the scholarly and educational world, distinctions comes very slowly as a rule." She hastened to assure Reid that members of the board had agreed to buy the property but needed time to evaluate its worth. She did, however, agree that Fast had not "kept up the buildings as well as she could."

Fast was asked to resign by the end of 1926. She claimed that she could not leave Paris immediately but would make arrangements to do so as soon as possible. She officially resigned in January 1927 and found temporary lodgings around the corner from rue de Chevreuse. Immigration records show that Fast did not return to the U.S. until August. For reasons unknown, Fast continued to give the impression to the AFDU leadership that she was still in charge at the Club.

Fast went on to become a prominent social activist and suffragist in the United States. She served as national chairwoman of the League of Women Voters' Cause and Cure Committee, and gave public lectures about peace issues, including the 1928 Kellogg Peace Treaty.

Dorothy Flag Leet (Barnard class of 1917), who had been Louisa Fast's secretary since 1924, took over as Club Director on January 1, 1927. Reid agreed that the American University Women’s could remain open.

Leet set to work immediately, developing ties with various women's groups, especially the IFUW, and reaching out to women's colleges in the United States in an effort to attract more students and programs to Paris. As Director, Leet was a public relations machine: she wrote articles about the Club, appeared on radio talk shows, and hosted receptions and dinners for French government officials, professors, and visiting dignitaries. She transformed the informal Wednesday teas by inviting speakers from the French academic community and also hosted annual Thanksgiving dinners attracting upwards of 100 guests. Other social contributions by Leet included establishing a robust lecture series and hosting the Pen Club's regular dinners. In 1929, she oversaw the entire renovation and restructuring of the property, which included new roofs, the addition of a large dining hall, and the creation of a new floor to house the artists' studios.

Despite some turmoil at the beginning of her directorship, Leet persevered, successfully leading the Club until 1938. In recognition of her service to French and American relations, the President of the French Republic, Albert Lebrun, conferred upon her the distinction of Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur in 1934.

For further details, see Joyce Goodman's article: Governing and Operating the American University Women’s Club House in Paris, 1921

Renaming 4 rue de Chevreuse

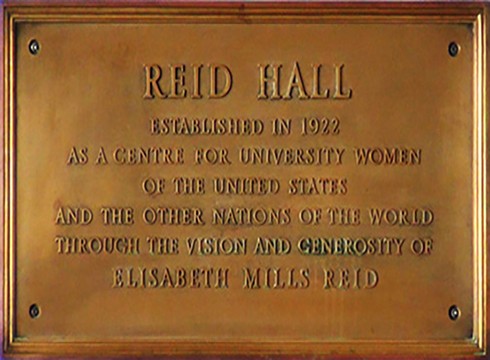

4 rue de Chevreuse was officially renamed Reid Hall in honor of Elisabeth Mills Reid and Whitelaw Reid around 1928. Archival records indicate that two proposals for the new name had been considered: Reid Paris Hostel and Reid House. In a June 2, 1928 letter to Dean Gildersleeve, Reid suggested naming it The Elizabeth (sic) Reid Foundation for American University Women, stating: "I was never very enthusiastic about either Reid Hall or Reid House," because she thought they sounded more like dormitory names than those of a club. After some negotiating, Reid Hall was finally accepted as the official name.

Between 1927 and 1928, the title of the property was transferred to a holding corporation, the Women's Realty Corporation, managed by the founders of the Club, which, in turn, leased the property to a membership corporation, Reid Hall Inc. The transaction was handled by the firm Harper, Slzapka & Harper (Donald Harper, letter to Reid, 1927).

Reid waived the rent of 5,000 francs per year, with the proviso that the Club be solely responsible for the maintenance of the property. A letter from Gildersleeve to Frederick Keppel, soliciting a grant from the Carnegie Corporation, reveals Reid's continued and unwavering commitment to the Club: "Shortly before her death, Mrs. Reid spent $100,000 repairing and improving the buildings." Gildersleeve described the property as "charming, so full of the atmosphere of old Paris" (December 2, 1933).

A few years after the property was renamed, Elisabeth Mills Reid died suddenly of pneumonia at her daughter’s home in St.-Jean-Cap-Ferrat on April 30, 1931. An editorial in the New York Times remarked on her passing: "In a day when 'society' had lost its moorings, and even its compass, she carried on the fine old tradition" (April 30, 1931, 22). After Elisabeth's death, Helen Rogers Reid assumed responsibility for the family's continued patronage of Reid Hall, its programs, and its students. Although planning for a commemorative plaque began in 1930, it was not installed until November 1932 in a simple ceremony.

Operations and Economic Downturn

In the interwar period, life at 4 rue de Chevreuse embodied the epigram "plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose."

As a university club, it remained a haven for women, drawing residents mainly from the American community. Its appeal was continually praised by the press and by the Club's many visitors. A 1928 article in the Times of India commented on the warmth and fellowship that residents, particularly those hailing from America and England, found at the Club: "It is a little bit of home, this club, tucked away in a corner of a foreign city, a place where you forget all about the Eiffel Tower or the Rue de la Paix, and talk about Fifth Avenue and Piccadilly Circus to your heart's content" (17).

In an advertisement published in the American Women's Club of Paris Bulletin, the Club's convivial ambiance was promoted:

To push open the heavy door at 4 rue de Chevreuse is to come into an atmosphere of cheerfulness and welcome. Built around three sides of a paved court, with a garden beyond, the old house has an atmosphere of both college and home. Trunks are coming in and out, girls are running about, in the summer tea is being served under the trees, in the winter the long gallery or the salons are filled with tables (Bulletin of the American Women's Club of Paris, February 1929, 412).

As Reid Hall evolved in the 1920s and 1930s, its objectives also changed: while women artists still formed part of the community, the Club mainly drew university women who came to study at the Sorbonne or the Collège de France, or to conduct research on scholarly projects.

The worldwide economic impact of the Great Depression and the threat of war throughout Europe brought Reid Hall's finances to the brink in the early 1930s. Fewer women could afford to travel abroad and even those who had the means stayed away from Western Europe as the political situation turned increasingly volatile. Parts of the Annex were shut in order to conserve heat and electricity, support staff were let go, and the board even considered a total shutdown of operations.

Leet's careful management saw 4 rue de Chevreuse through its difficult times. Every effort was made to advertise the comforts this Parisian property afforded its residents in the hope of increasing the Club's revenues. A brochure was printed and mailed to college deans and other educational organizations, leaflets were sent to women's clubs in the U.S. and England, and several influential people were asked to write statements of support (Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Emma Woolley, Virginia Gildersleeve). Gildersleeve and Leet solicited funds from various sources and sent urgent letters of appeal encouraging American membership. Leet reduced her own salary, and several members of the staff followed suit, with some even generously offering their services free of charge.

Elisabeth Mills Reid continued her support of the Club by paying for much-needed renovations and upgrades. Between 1928 and 1929, she spent $100,000 on a complete overhaul of the facilities.

Some financial assistance came via the AFDU in 1933. Then, in 1934, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs contributed 20,000FF (French francs) to the Club, and the University of Paris contributed 2,000FF. In his letter announcing the gift, the Minister complimented Leet on the “remarkable effort undertaken by this Association, under your direction, towards forging intellectual relations between France and the United States” (Howard 10). A letter from Dean Gildersleeve to Frederick P. Keppel in November 1935 reveals that the Carnegie Corporation, of which Keppel was the president, had granted Reid Hall for the second time a much-needed gift of $10,000 to cover operating costs and keep the club open another year:

Reid Hall has been able to remain alive and continue its active work. [...] Since Reid Hall started, about ten thousand American college women have stayed there, and have learned through it some friendly understanding of France and the French (November 29, 1935).

To support the Club's activities, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued granting a small subsidy of 18,000FF each year until 1939 (Memo to Joint Operating Committee of Reid Hall, May 17, 1939).

Though the economic situation at the University Women's Club remained precarious as the 1930s progressed, several First Ladies became affiliated with the Club, including Lou Henry Hoover, Grace Coolidge (who dined there in the spring of 1936), and Eleanor Roosevelt. Perhaps Gildersleeve and Leet hoped that these illustrious affiliates could attract more American memberships and improve Club finances.

Besides the IFUW and AFDU, other organizations were headquartered at Reid Hall or hosted regular events on-site: the PEN Club (acronym for Poets, Essayists, and Novelists), the Association of French Women Architects, Lawyers, and Doctors, the Paris branch of the League of Nations, and the Société féminine nationale de rapprochement universitaire. As the number of Americans in Paris grew, increasing numbers of students and alumnae from American universities and colleges lived at the Club or attended its events. Student cohorts and alumnae came primarily from: the University of Delaware (ca. 1935 – 1938), Bryn Mawr (ca. 1929 – 1933), and Vassar (ca. 1927 – 1935). Though Smith College students did not reside at the Club (they were assigned to live with French families), many spent time at Reid Hall for social occasions.

By 1930, American students in Paris numbered well over 5,000. According to Hugh Smith, head of the American University Union, “[…] America is one of the chief contributors to the greatest international current in the migration of students that the world has ever known” (161-162). In order to assist this growing population of students in Paris, the American University Union, which had been founded during WWI, made concerted efforts to advise American students who were enrolled at University of Paris. Dorothy Leet was also active in the Union’s efforts.

On February 12, 1931, the New York Herald Tribune hailed Reid Hall as a "...Mecca of all nations for American University Women" (n.p.). On average, about 40 international women resided at the Club at any given time. The year 1937 provides a perfect example of the diversity of nations: 19 Americans, 7 French, 4 English, 3 Swiss, 3 Hungarians, 2 Dutch, 2 Irish, and one each from Canada, Australia, South Africa, Scotland, and Belgium. As Dorothy Leet reported, Reid Hall was a social and information hub for myriad students:

While the American university women who live here are not necessarily studying, much of our work is naturally with students… we have an information bureau and a carefully selected list of French families with whom students can live and of private tutors (New York Herald Tribune, February 12, 1931).

The Club's ability to provide the comforts of home while also providing opportunities for young Americans to sample the French way of life made it a unique "third space." Gertrude Homans Cooper, who became the Club's director in 1938, expressed this esprit de corps in a report to the joint operating committee (May 17, 1939):

As a place of residence, Reid Hall is unique in Paris and thanks to Miss Leet and Miss Porter it has its place in the intellectual life of the city. The charm of the old house and garden exercises its spell on everyone who comes. Because the house is rambling and built around a courtyard, it is more expensive to keep up, but I doubt very much if people would be eager to come here if it were a completely modern type of building, entirely American in atmosphere.

Social Life at the Club

Miss Leet every now and then gives a dinner to liven things a little. Nothing can be more charming than those functions. On two occasions I have had the pleasure of being "the speaker of the evening." It was delightful to notice that every historic or literary allusion was registered, and that when I was asked to substitute my native French for my adopted English not a single nuance seemed to be missed. Clearly those American girls go home with two souls instead of one [...] I assure you Reid Hall may be a blessing for Smith College or Delaware University, but it is an even greater one for Paris (Abbé Dimnet, 7).

As the headquarters of the International Federation of University Women (IFUW) and its French association (AFDU), the Club hosted grand social gatherings to bring together women from all around the world. In March 1923, for example, there was an evening reception at the Club, at which Alys Russell, American relief organizer and the first wife of Bertrand Russell, and Theodora Bosanquet, suffragist and former secretary to the novelist Henry James, spoke on the international aims of the Federation. Russell and Bosanquet both stressed the value of the Federation "as a means of uniting in bonds of real understanding and sympathy those members of the different nations who are likely to profit most by international contacts and whose influence, as teachers, on the rising generation is of the highest importance." The program also included a performance of Mozart and Gabriel Fauré sonatas by violinist Seymour Whinyates, accompanied by the Marquise d'Elbée (Journal of the American Association of University Women 21).

Virginia Gildersleeve, M. Charlety, Rector of the University of Paris, Mme Veiller Duray, president of the French Federation of University Women, at the Council of the IFUW, in Reid Hall's Grande Salle. Photograph retrieved from the Barnard College Alumnae Monthly, vol. 27, no. 1, October 1937, p. 5.

The directors of the American University Union were invited to speak about the experiences of American students at the University of Paris:

- J.D.M. Ford, November 3, 1925, reception (new director)

- Charles B. Vibbert, November 17, 1927

- Paul Van Dyke, November 7, 1928

- Hugh Smith, March 12, 1930

- Horatio Kranz, November 5, 1930, November 18, 1931, November 2, 1932, and December 6, 1933.

Many notable women were also invited to speak at 4 rue de Chevreuse, including Virginia C. Gildersleeve and other university deans or professors, who delivered lectures on a wide variety of topics. Below are some examples showing the breadth and depth of those addresses:

- Alys Russell returned to the Club in 1927 as guest speaker for a reception honoring Bryn Mawr students and alumnae. She spoke about Crosby Hall (London), which the British Federation of University Women had leased in 1925, and which had been expanded to include the offices of the IFUW.

- Dr. Ellen Gleditsch, Norwegian radiochemist working at the Institut Curie, spoke on April 25, 1928.

- Margaret Proctor Smith, a writer and lecturer who had just spent two years living and studying in China, during which she also traveled to the Philippines, India, and Egypt, gave a speech praising the Chinese nationalist movement in July 1929. She was described in an article in The China Weekly Review as "the ambassador of good-will for the Chinese nationalist movement" (July 6, 1929, 245).

- In November 1930, Dorr Bothwell spoke on Samoan songs and dances, presenting sketches and watercolors from her extensive travels.

- Frances Perkins, U.S. Secretary of Labor, came to Paris on July 30, 1936 to address the Second Congress of the International Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs. She was received at the Elysée Palace by French President Albert Lebrun and met with the French Minister of Labor. Given the large number of suffragists who resided at the Club or served on its Board during this period, it is not surprising that a tea was given in her honor. The New York Herald Tribune covered her visit, including her exchanges with women at the Club: "In her interview, to the astonishment of her feminine interrogators, Miss Perkins indicated that she did not believe married women should work unless they needed money. Miss Perkins herself is the wife of Paul Wilson. 'The right of married women to work,' said Miss Perkins in answer to a question, 'depends, I believe, on whether they need to work. I personally do not believe in a woman's working simply to pass the time away, but there are often circumstances, perhaps extraneous to her immediate household, which make added income necessary'" (July 31, 1936, 4A).

The University Women's Club was especially active in French-American international relations. Major issues such as women’s rights, international politics, diplomacy, law, economics, and governance were analyzed and discussed at Reid Hall. The Club hosted a wide range of activities – weekly teas, bi-monthly receptions, monthly dinners, luncheons, and concerts – that frequently included keynote speakers. Leet also marshaled the help of other organizations who co-sponsored events with the Club.

The PEN Club, which stood for the free exchange of ideas irrespective of national or political allegiance, hosted monthly dinners where writers could debate about freedom of speech and the circulation of ideas. German novelist Thomas Mann, Czech journalist and writer Karel Capek, English novelist and playwright John Galsworthy, and many other luminaries were among the guest speakers. The Paris Branch of the League of Nations, the Association of French Women Architects, Lawyers, and Doctors, and various other groups also hosted receptions at the Club.

Beyond bringing diverse speakers and thinkers to Reid Hall, Dorothy Leet also wanted its residents to move outside of their comfortable American bubble, and be immersed in French cultural and academic life:

We wish to give the American student living at the club ...some idea of French social life and French culture. Now we have these students as comfortably housed as they could be housed in America, but we do not wish them to become an isolated group of Americans mingling with only their countrymen (New York Herald Tribune date, 1928).

As a means of reinforcing the French language on-site, especially over meals in the dining room, the AFDU sponsored five residential scholarships for French students. Cultural visits were organized to the Louvre and other museums, as well as to Versailles, Chartres, and Fontainebleau. French scholars also spoke at teas and dinners. Some were Reid Hall regulars:

- Nadia Boulanger, French composer, conductor, and teacher (1927, 1937, 1938)

- Abbé Henri Breuil, prehistorian (1929 and after WWII)

- Pierre Comert, director of the Information section of the League of Nations from 1919 to 1932 and the head of the Information and Press Service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1933 to 1938 (1927, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938)

- Benjamin Crémieux, writer, literary critic, translator (1927, 1930, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1939)

- Ernest Dimnet, Catholic priest, writer, and teacher (1927, 1930, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1935, 1939)

- Étienne Gilson, historian, philosopher, Académie française, Collège de France (1929, 1932, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1938)

- Paul Hazard, historian (1932, 1933, 1935, 1938, 1939)

- Pierre de Lanux, writer, diplomat, and teacher, Paris Bureau Chief, League of Nations (1928, 1931, 1932, 1934, 1935, 1937, 1938)

- André Siegfried, sociologist and historian (1928, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1937, 1938)

- Jules Romains, writer and poet (1936, 1937)

- Firmin Roz, essayist and member of the Institut de France, who was later decorated by the Vichy Regime (1929, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934, 1937, 1938).

There were also numerous public recitals and concerts, especially during the annual Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners. In a letter to Helen Rogers Reid, Leet described the very festive 1931 Christmas dinner:

Christmas day we gave our usual dinner, and there were about 115 guests present. The hall was decorated with holly and mistletoe, and we had a big Christmas tree in the library. Our guests enjoyed very much the Russian singers who added a great deal to the gaiety of the occasion. I did not invite any special guests for the occasion since there were no stray foreigners in town. Miss Janet Scudder, who has one of our studios, invited Gertrude Stein, and the young students were delighted to have this opportunity of talking to her (1931).

An amusing guidebook published in 1929 for young ladies, Paris Is a Woman's Town, sheds light on the more wholesome social activities that attracted Americans to the Club:

Homelike social gatherings as comforting as long distance telephone talks with the folks back home in Missouri, are held on Sunday nights at the American University Women’s Club, 4 Rue de Chevreuse, with a musical hour given by amateurs studying in Paris to become professionals and community sings during which everybody lustily roars "Dixie'" and "Nearer, My God, to Thee." Afterward there is dancing to a rather weak improvised orchestra or to somebody’s volunteer piano playing. The whole entertainment is informal, with Lady Betty Foster, official Latin Quarter chaperon, sitting discreetly against the wall to receive the greetings of her artistic family (167).

The guidebook goes on to describe the hospitality the Club offers to "thousands of lonesome women every year […] presided over by fair-haired, good-tempered Dorothy Leet, Barnard graduate" (171). Interestingly, the authors claim that Club residents frequently engaged in sports: "Fencing also is good for keeping in physical trim in Paris where continuous bad weather often makes outdoor exercise difficult. Girls at the American University Women's Club frequently arrange small private classes" (214).

Amid all the social delights and fun, 4 rue de Chevreuse also experienced its share of crises. There were instances of young women rebelling against their parents; for example, Ann Moorhead’s (mis)adventure on her last day at the Club was reported by The Washington Post in September 1934:

This morning, two hours before she and her mother were due to take the boat train for the Aquitania, Ann walked out of the American University Women's Club. Because she had little money, no friends in Paris and knew French but slight, her alarmed mother asked police and Embassy officials to try to find her. During the day they watched dancing schools in the belief the missing girl would attempt to enroll in one. "She was resentful," Mrs. Moorhead explained, "because I refused to consent to her remaining in Europe to study dancing. She has always been independent. Her disappearance was intended to prove that she was grown up. I told her she could have all the independence she wanted at home, but I couldn't let the ocean separate us." A few hours were enough, her mother said tonight, to convince her that independence "was not what she expected," so she changed her mind and came home (September 2, 1934, M1).

Residents of Reid Hall also suffered from bouts of mental illness. In some cases, overworked students succumbed to their anxiety and required treatment at the clinic or even had to return home.

Far more frequent were descriptions of the pleasant experience of life at the Club, such as the account written by Barnard alumna Louise Trueblood (class of 1912) of her two-week stay at Reid Hall in the summer of 1935:

It was with slight misgvings that I had gone to Reid Hall in the first place, for my friends had not been encouraging when I told them where I was going to stay. I had heard such remarks, as “Is that the kind of place you want to stay at?" “Uninteresting food," “dormitory atmosphere.” “You'll meet only Americans there.” But from the instant that I stepped into the cobble-stoned courtyard with its mossy well and its geranium and ivy-parterres, and saw in front of me the garden shaded by the gnarled boughs of the ancient Judas tree, peace and charm seemed to envelop me, and the impression grew with the length of my stay. No one can really appreciate the peace and dignity of Reid Hall who has not stayed in the typical small inexpensive French hotel with its stuffy rooms, garish furniture, violent wall paper and pervasive smell of cooking [...] Some day I hope to get back to Reid Hall with enough time to do all the things that I had no time for last summer. I want to read books in that fascinating library, attend lectures in the impressive lecture room, explore thoroughly all the old building, and sit at my ease in the glass enclosed gallery and read the newspapers (May 1936, 21).

On the Brink of War

Tensions at Reid Hall were running high throughout much of the 1930s due to the threat of conflict in Europe. As early as October 2, 1935, Leet had written to Gildersleeve voicing her concerns:

The war situation continues to be serious. We are obliged by the City to make preparations against air attacks, and to post a large notice about such arrangements in our entrance hall before the end of the month. This will probably scare away the few students who have arrived.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War brought a group of refugee university women to Reid Hall in August 1936. In her letter to Gildersleeve about the Club's Thanksgiving celebration in November, Leet mentioned that Clara Campoamor, a Spanish feminist and political exile, had attended the dinner and was anxiously hoping to secure a teaching position in the United States.

Though Leet was discouraged by the mounting expenses at Reid Hall, she continued sending regular reports to Gildersleeve and ensured that the Club always ran smoothly. In February 1938, she explained two unusual expenses in the operating budget:

Paris has been filled with swarms of rats, which have chewed their way through the most solid wooden doors, so that we have been obliged at the Club to build metal frames for the lower sections of the doors in the kitchens, food closets and dining room. Also, the beautiful ivy vine which climbs seven floors of the apartment wall facing the Annex has been filled again with thousands of starlings. They destroy the garden below, - the earth, bushes, box hedge, etc.,- and last year we spent a thousand francs replacing the damaged section. We have therefore been obliged to clip back the long branches of the vine over this large surface..

In late 1937, after nearly 15 years as the Club’s devoted director, Dorothy Leet resigned from her position in a formal letter to Gildersleeve :

After long consideration, I have come to the conclusion that I must give up my work at Reid Hall. I make this decision with tremendous regret, not only because I am devoted to the Club and have thought of nothing else for the last fourteen years, but also because the change in my own life, the breaking of many ties, etc. is difficult. […] I am now convinced that the French are the only people who can run the Club. They could change certain ways of doing things, and people would accept certain standards from them which they would not accept from us. If the Club belonged to the University of Paris, to be run by the French Federation of University Women, it would be tax-free and could probably receive subsidies (November 6, 1937).

On March 17, 1938, a farewell dinner was organized in Leet's honor. Various toasts were given by former residents and colleagues, including sculptor Janet Scudder; scholars Mary Boyle and Suzanne de Saint Mathurin; and Jean Gardiner and Miss Reese of the University of Delaware group. Leet received several presents, including an antique porcelain vase from Club members and a silver gift from Reid Hall's employees. During the dinner, an international group of students performed a pantomime. The guests represented 11 countries and 9 U.S. states (New York Herald Tribune, March 18, 1938, n.p.).

That summer, in recognition of its important place in French-American relations, Reid Hall received the prize of the Bonne Volonté Franco-Américaine (French-American Association of Goodwill headed by André Maurois and M.L. Julliot de la Morandière). Founded in 1925 by Americans Anne Morgan and Anne Dike as well as André Siegfried of France, the Association honored the aid given to France by American groups during and after WWI. The prize was awarded every year to an educational organization that promoted French language and culture in the U.S., or facilitated amicable relations between young people of both countries. Reid Hall was commended for its excellent work in supporting American university women studying or working in France. According to the New York Herald Tribune, the prize recognized Reid Hall for "[...] promoting friendship and understanding between the two nations and for disseminating French culture" (July 3, 1938, n.p.). Reid Hall was awarded this prize again in 1964.

Additionally, the Ministère de l'éducation nationale gifted Reid Hall three large Sèvres porcelain vases, which are still on view. Leet thanked the Minister for this thoughtful gesture:

On behalf of the Reid Hall Board of Directors, I would like to thank you for the magnificent gift that the Government has kindly given us. I cannot express to you enough our gratitude for the way in which the Government has associated itself with the French-American Goodwill, which has done us the great honor of awarding us its prize this year. We are both happy and very proud to own these splendid works of art from the Manufacture de Sevres (August 17, 1938).

Leet sailed for New York on the Ile-de-France liner on April 8, 1938 to take up the position of Secretary of the Foreign Policy Association. One of the most successful eras at Reid Hall ended with her departure – but Leet would not be gone forever and Reid Hall would eventually be reborn under her stewardship.

Reid Hall Closes

Leet was briefly succeeded by her long-time assistant Sarah Porter (Wellesley class of 1917), who had worked at Reid Hall since 1927. At the end of 1938, Porter left Paris for Washington, D.C., where she held the position of secretary to the President of the American Foreign Policy Association until 1950.

Porter was officially replaced by Gertrude Homans Cooper on October 1, 1938. The New York Herald Tribune reported that Cooper was a graduate of Radcliffe College and a former director and vice-president of the American Association of University Women. She had taught French and German in secondary schools before taking on the role of manager for the Martha Washington residential hotel for women in Portland, Oregon, a post she gave up in order to lead Reid Hall (New York Herald Tribune, July 25, 1938).

As the world inched terrifyingly toward war in the latter half of 1938, Cooper reported to Gildersleeve about the tense farewell tea held in honor of Porter's honor:

On the 28th of September, the Club had a tea which served as a farewell to Miss Porter and an introduction to the new director. It was on the morning of that day that we felt there was but little hope left of averting war, so all who came were anxious and preoccupied. Before they left, however, word was sent us from a news agency that there was to be another conference with Mussolini included. Immediately, the whole spirit of the group changed, and our party ended in a much happier mood (October 12, 1938).

Regular Club activities continued under Cooper's leadership until summer 1939. In a letter to Gildersleeve, Cooper reports on those dark days:

The week before war was declared the government urged all French people as well as foreigners to leave Paris if they could [...] People still come in, we have baggage belonging to women who left and intended to come back and it takes so much time to get anything done now [...] A large part of the population has left the city. The little shops are nearly all closed and many houses have closed shutters [...] At night, we are in darkness [...] The first days I felt as though I were being driven by a whirlwind and must do everything at once. The tension in the air, in the streets made one feel like running (Sept. 13, RH Archives).

According to the student register, Reid Hall officially closed on September 3, 1939 (RH Archives). Cooper dismissed the personnel, giving each one a bonus of 500FF. She left 4 rue de Chevreuse on October 11, entrusting the property to a British caretaker and his wife, as well as a lawyer, Victor Soulas, who would manage business matters (report to the Board, Dec. 6, RH Archives).

American women would not return to 4 rue de Chevreuse until 1947.

Consult the sources for the University Women's Club history