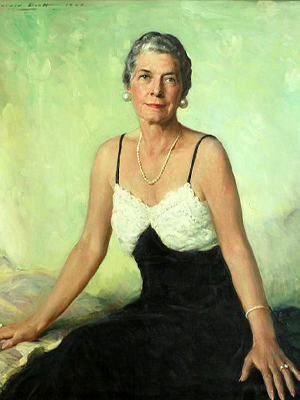

Virginia C. Gildersleeve, 1877 – 1965

Born in New York in 1877, Virginia Crocheron Gildersleeve began her undergraduate studies at Barnard in 1895, just six years after the college was founded. After graduating in 1899, she earned an MA in medieval history (1900) and a PhD in English and Comparative literature (1908) at Columbia University. She was appointed to the Barnard deanship in 1911 by Columbia President Nicholas Murray Butler, a lifelong friend, and served as Adviser to Women Graduate Students at Columbia.

Throughout her career, Gildersleeve was a leader who paved the way for young women in education, administration, and civic responsibility. Her activities and creations are telling examples of her profound commitment to women and internationalism, whether as Dean of Barnard College, founding member of the International Federation of University Women, Chair of the Advisory Council of WAVES (the Navy's women's unit), Chair of the American Council on Education, or a founding member of the Seven College Conference of Women's Colleges. She was appointed to the United Nations Charter Committee, and was also a member of the U.S. educational mission to Japan. At Columbia and Barnard, Gildersleeve opened doors for women in the medical, law, and engineering schools.

As Dean of Barnard College for thirty-six years, Gildersleeve was a key player in Reid Hall's long history but many biographies often gloss over the important work she accomplished in Paris. This account will not delve into the already well-documented aspects of her life and career but will instead foreground her contributions to the evolution of 4 rue de Chevreuse. Correspondence and reports in the Columbia and Barnard archives bear witness to her steadfast dedication to the affairs of Reid Hall, whose board she headed from c. 1922 – 1952. During WWII, when the University Women's Club was replaced by the École normale supérieure des jeunes filles de Sèvres, she remained in regular contact not only with French and American heads of state, but also with the network of Americans who had supported the Club. Even after she stepped down from the Barnard deanship in 1947, she worked assiduously with Dorothy F. Leet to usher in a new chapter for Reid Hall.

Gildersleeve’s interest in 4 rue de Chevreuse was closely tied to her work in international relations and the advancement of university women. Her values aligned with Elisabeth Mills Reid’s commitment to French culture, women artists, and nurses. Furthermore, Elisabeth’s daughter-in-law, Helen Rogers Reid, was a Barnard alumna (1903), as, too, were Roselle Lathrop Shield (1898), and Dorothy F. Leet (1917), both of whom would direct 4 rue de Chevreuse in different periods.

As early as 1918, Gildersleeve began exploring the possibility of creating an international network of university women who “United globally […] could work for understanding, friendship, and foster peace” (Rønning 2). During the 1918 visit of the British educational mission to the United States, Gildersleeve met Caroline Spurgeon (University of London) and Rose Sidgwick (University of Birmingham, England). All three met again in London on July 11, 1919, together with Winnifred Cullis (Chair of Medicine at the University of London). In common accord, they founded the International Federation of University Women (IFUW). Its first conference was held in London in 1920, with representatives from nine national federations in attendance (Rønning 2).

Prior to the founding of the IFUW, Gildersleeve already had her sights on 4 rue de Chevreuse as a possible meeting place for women. In a letter dated October 21, 1918, she solicited the advice of Roselle Lathrop Shields, who had directed the Girls’ Art Club and maintained administrative oversight while the property functioned as a Red Cross hospital. Encouraged by Shields, who nevertheless felt there were many roadblocks to implementing the idea (November 26, 1918), Gildersleeve outlined her plans to a group of university women, which she then summarized in a letter to Alice Parsons, a prominent Smith Alumna, whom she “commissioned” to visit 4 rue de Chevreuse as part of the broader project to form an international network of university women:

The Paris centre might, it seems to me, begin on a small scale as a headquarter for information and sociability, for University women, especially students. It should not, I think, be primarily concerned with supplying a place of residence, though it might do this in a small way incidentally. Its aim should be chiefly to bring the university women in touch with one another and with characteristic phases of French life and thought. It would be unfortunate to have it confined to American college women alone. It might begin as an Anglo-American centre and later take in women of other nationalities. It could be largely supported by a membership fee, but would undoubtedly need some contributions to finance it at the beginning (Letter from Gildersleeve to Parsons, February 10, 1919).

Parsons returned from her May trip to England, France, and Italy, during which she had met with Caroline Spurgeon, Roselle Shields, and Elisabeth Reid, among many others. Parsons “found a really profound interest in the project as a basis of international, academic and feministic understanding” (letter to Gildersleeve, May 14, 1919). With this information in hand, Gildersleeve approached Elisabeth Mills Reid, who demonstrated a keen interest in the project as long as it could be launched after the Red Cross had vacated the premises. Reid explained that the buildings belonged to her and that she would continue to pay the lease on the land ($5,000 per year) for the upcoming seven years, provided that the women would buy the land when the lease expired (at a cost of about $100,000). She also said she would then turn the buildings over to the group (stated in a letter from Gildersleeve to Parsons, May 28, 1919). According to Gildersleeve, Reid was likely attracted to this idea through:

[…] the eyes of her brilliant daughter-in-law, Mrs. Ogden Reid (Helen Rogers), for whose judgment she had great respect. Mrs. Ogden Reid, now President of the New York Herald-Tribune, was a graduate of Barnard College of Columbia University, deeply interested in international affairs and naturally associated with the small group of American university women who saw a vision of what this Paris centre might accomplish (1950, 315).

Gildersleeve confirmed that this group, referred to by Reid as “the ladies,” was interested in retaining the property and would wait until June 1922 (cable to Reid on February 7, 1921; letter to Reid on February 9, 1921). She visited the property in June 1921 and expressed her pleasure at seeing the many upgrades that had been realized since her last visit in 1909 (Gildersleeve to Reid, July 6, 1921).

Elisabeth Mills Reid officially “gave use of the property” rent-free for five years to the following board of managers (document signed on June 1, 1922):

- Virginia Gildersleeve, Chair (Barnard)

- Mrs. Elon H. [Blanche Ferry] Hooker, Treasurer (Vassar)

- Miss. M. Carey Thomas (Bryn Mawr)

- Mrs. Edgerton Parsons (Smith)

- Mrs. Ogden Reid (Barnard)

- Mrs. William Morton Wheeler (Wellesley)

- Miss Virginia Newcomb, Secretary

The formal opening of the Club took place in July 1922 at the second conference of the IFUW at 4 rue de Chevreuse, where its French chapter had been established with Marie Curie as honorary president (1922 – 1934). Gildersleeve was named President of the IFUW from 1924 – 1926 and again from 1936 – 1939.

When Reid Hall was thus born, just after the First World War, it was a time of active ferment in the field of international education, where many new organizations were being founded in an effort to guard against the development of another similar cataclysm. Alas, they were not successful, but our hopes were great and we tried very hard. As Chairman from the beginning of the Board of the American University Women’s Paris Club, later Reid Hall, I was much interested in helping to link it with the other groups then growing up, for I think it most unfortunate when organizations with a similar purpose rival and duplicate each other instead of collaborating happily. So we worked with the Institute of International Education, the American University Union in Paris and in London and especially the International Federation of University Women. Of this great organization the French member, the Association des Femmes Diplômées des Universités, has always had its headquarters at Reid Hall and has been of inestimable help to us in linking us closely with French life and thought. We owe much to our French sisters. The American member federation, the American Association of University Women, has also been a sponsor and supporter of our work, sometimes formally, at other times without constitutional connection but warmly giving sympathy and encouragement. To the French government we owe immense gratitude. It has encouraged and aided us in many ways and in times of financial stress it has honored us with a subsidy. Our friends the Ambassadors who have during our lifetime represented the United States in Paris have also been of inestimable help (Gildersleeve 1950, 316-317).

The Club faced its first serious challenge in 1926 when Elisabeth Mills Reid wrote to express her disappointment not only with the upkeep of the property but also with the attitudes of its residents. From her perspective, they seemed more interested in travel and fun than in serious study. Gildersleeve harnessed all her energy and intelligence to rectify the situation: she let go the current director, Louisa K. Fast, and installed Fast’s assistant, Dorothy F. Leet, as the new leader, who would go on to reign over the property for close to forty years. Leet and Gildersleeve remained in constant contact via letters, reports, and cablegrams – with Gildersleeve visiting 4 rue de Chevreuse on a regular basis and Leet traveling to the United States each year.

The onset of WWII brought the Club to a standstill. Dorothy Leet had already returned to the U.S., as had her replacement, so Gildersleeve became the principal interlocutor concerning the fate of Reid Hall. She evokes her grim 1939 Paris visit in her autobiography, Many a Good Crusade:

On a newspaper bulletin board I read accounts of alleged atrocities perpetrated by the Poles on German women. In Paris the following morning the news of the Russo-German Pact told us that war was certain. Dean Margaret Morriss of Pembroke College, President of the American Association of University Women, had traveled down from Sweden with me. We went to stay at Reid Hall, but in the afternoon we wandered out across the river and sat in the Tuileries Gardens watching the flowers and the fountains playing and the children at their games. We knew that it would be a long time before we saw again this familiar scene. That night, in the Director’s Salon of Reid Hall, with the light dimmed very low, Mrs. Cooper, then director, her young secretary Barbara Howard, Dean Morriss and I, and later two French friends of ours, M. and Mme. Puech, discussed how best to evacuate the residents and to secure some protection for the buildings (162-163).

Back in the U.S., Gildersleeve communicated with the Club's Board of Directors, the leadership of the French chapter of the IFUW, and Helen Rogers Reid to ensure that the property could weather the adversities of another major war. Gildersleeve recalled those months of uncertainty:

At first we tried to work out a plan for housing Polish university women in Reid Hall. […] From the moment the Germans entered Belgium and Holland it was clear that Reid Hall would probably not be a safe place to assemble refugees. Then came the flood of Belgians, and in this emergency Reid Hall was opened for a time and some Belgian teachers and their families took refuge there. […] But all refugees had to push on towards the South, for soon the Germans came and darkness settled on the City of Light. […] As the darkness of the occupation spread over France our French friends found a way to protect Reid Hall as well as was possible under the circumstances. The property was loaned by us to the Ministry of Public Instruction for the use of the École Normale de Sèvres (1950, 319-320).

When the war ended in 1945 and the École seemed unwilling to leave the premises, Gildersleeve was instrumental in retrieving Reid Hall. She contacted her numerous governmental and university connections, and, more importantly, she convinced Dorothy Leet (who did not really need much persuasion) to go back to Paris and negotiate the rightful return of the property to the Board of Directors. When Reid Hall was finally reclaimed by its American membership in 1947, both Leet and Gildersleeve worked hand-in-hand to rebuild a network of resident scholars, and to open Reid Hall’s doors to the growing number of American graduate and undergraduate students in Paris. The French Federation of University Women was given an office, and the International Federation of University Women continued to use Reid Hall as its Paris headquarters.

With Leet once again at the helm, this time as President, Reid Hall gained significant prestige as a French-American educational center and a popular site for international conferences and academic meetings. As in the past, Leet sent regular reports to Gildersleeve and to members of the Board of Directors, detailing daily activities at 4 rue de Chevreuse. In 1950, Gildersleeve wrote a lengthy article on Reid Hall for the Journal of the American Society of the Legion of Honor; her concluding remarks ring true even today and bear witness to her work and that of the many women who supported Reid Hall’s mission:

So our centre, though small in size compared with the vast organizations working in the educational field, has really achieved happy results, promoted knowledge and international understanding, and opened new visions of life to many a young student. It remains very elastic, ready to explore and try out new ideas. It has high hopes for the future (324).

Gildersleeve was a champion of all educated women, whether married or single. She decried the discrimination women who chose to spend their lives with other women faced in her autobiography, a poignant defense given her own life experiences with Caroline Spurgeon and other partners. Leaders like Gildersleeve and Leet ensured that Reid Hall remained a haven for those who led unconventional lives, including classicist Jane Harrison and her partner, poet and writer Hope Mirrlees, who lived there from 1922-1925.

Her commitment and her vision of Reid Hall as a global university women's center and as a study-abroad site paved the way for its future iteration as the European intellectual hub of Columbia University beginning in 1964. From her formative years as a Barnard and Columbia student, to her decades of leadership as Barnard's Dean, to her unparalleled leadership in internationalism and women's causes, she remained one of the primary driving forces behind the survival and success of Reid Hall in the 20th century. Though many exceptional women had a hand in steering and sustaining 4 rue de Chevreuse, few achieved such heights of power and international renown as Virginia Crocheron Gildersleeve.

Sources

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Roselle Shields, February 7, 1919. Gildersleeve papers. RH archives.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Mrs. Edgerton Parsons, February 10, 1919. RH archives.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Mrs. Edgerton Parsons, May 28, 1919. RH archives

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Elisabeth Reid, September 18, 1920. Reid family papers, box 10B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Cable to Elisabeth Reid, February 7, 1921, Reid Family Papers, box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Elisabeth Reid, February 9, 1921, Reid Family Papers, box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Elisabeth Reid, February 21, 1921, Reid Family Papers, box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Elisabeth Reid, July 6, 1921. Reid Family Papers, box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. Letter to Elisabeth Reid, February, 1921. Reid family papers, box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia C. Many A Good Crusade. New York: Macmillan, 1954.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia C. “Reid Hall in Paris.” Journal of the American Society of the Legion of Honor, vol. 21, no. 4, Winter 1950, pp. 313-325.

- Le Boutillier, Cornelia Geer. “Dean Gildersleeve.” Barnard College Alumnae Monthly, October 1934, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 8-9. Barnard Digital Collections.

- Parsons, Mrs. Edgerton. Letter to Gildersleeve. May 14, 1919. RH archives.

- Reid, Elisabeth. Draft of a letter she sent to Gildersleeve, which seems to have been dated January 26, 1921 (based on Gildersleeve’s response on February 26, 1921). Reid Family Papers, Box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Reid, Elisabeth. Draft of a letter sent to Gildersleeve, in response to the February 7, 1921 cable. Reid Family Papers, Box 12B, Library of Congress.

- Rønning, Ann Holden. “Inspiring a Vision: Pioneers and Other Women.” Graduate Women, 2019, pp. 1-29.

Archives consulted

- Carnegie Corporation Records, Series III.A Grant Files: (box 16, folders 9 and 10): http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/eresources/archives/rbml/Carnegie/index.html

- Gildersleeve, Virginia Crocheron papers (Barnard): https://clio.columbia.edu/catalog/11453680

- Gildersleeve, Virginia Crocheron papers (RBML): https://clio.columbia.edu/catalog/4078806