Elisabeth Mills Reid, 1858 – 1931

American girl students in Paris may justly feel that they have two fairy-godmothers whose loving care and thoughtfulness is a real benediction (Cowles 404, referring to Elisabeth Mills Reid and Grace Whitney-Hoff, who founded the Foyer internationale des étudiantes).

More than a fairy godmother, Elisabeth Mills Reid was a philanthropist of the highest order, donating not only her time but also her money to advancing projects in the arts, medicine, and education. She was also an advocate for global understanding, French-American relations, and women’s agency. Although Reid was a consummate hostess, she was "[...] a reserved woman, with very little personal magnetism, but one must admire her inward and spiritual graces, even if they do sometimes seem incased (sic) in ice” (Andrews 6). Others describe her has having "[...] the most commanding presence owing to a mixture of candor, humor, self-confidence, and poise that seemed to draw people to her, if not in warm friendship, then certainly in awe" (Niemczyk). And, indeed, she always succeeded in rallying people to her causes, establishing and funding nursing schools, hospitals, and sanatoriums.

Most importantly, Reid bought the buildings at 4 rue de Chevreuse in Paris, lending them to various educational initiatives and to the Red Cross. For forty years, she was the primary and unwavering patron who enabled the property to grow and evolve. During this time, she corresponded regularly with local administrative staff and visited Paris at least once a year, casting an eagle eye over its operations and general appearance. On several occasions, she threatened to withdraw her financial support if conditions did not meet her impeccable standards. In 1918, for example, she sent strongly-worded missives to Red Cross officials concerning the quality of the food served in the dining room and what she perceived as unprofessional leadership practices. According to her biographers, she applied the same vigilance to all her undertakings: “She not only contributed large sums but kept in close touch with the operations of the institutions she supported” (James 132). In 1926, the University Women's Club director was dismissed after Reid complained about the shabbiness of the property and degraded ambiance. Her elegant personal touch could be detected in all the causes she sponsored for she left no stone unturned, lending hospital food a gustatory twist or imparting grace and refinement to even the most functional of settings.

Virginia C. Gildersleeve, Dean of Barnard College, best characterized Reid's magnanimity:

First in my mind as I look back is the gracious figure of Mrs. Whitelaw Reid, whose name our institution now bears. Of all the wealthy persons I have known Mrs. Reid seemed to me the most sound and just, least open to flattery, and most interested in the human touch, in the welfare of individuals. [...] Herself a woman of the great world of international affairs, she was glad to help develop others with some taste of rich international experience. (1950, 314, 315).

Born in New York City on January 6, 1858, Elisabeth was the only daughter of Darius Ogden Mills and Jean Templeton Cunningham. Her older brother, Ogden Mills, was born in 1856 and later became a financier and patron of the arts.

Elisabeth was quite devoted to her father, with whom she would spend much time traveling and working. After having been homeschooled in California, she was further educated at a school for girls at 26 rue Ganneron in Paris. The school was run by Aline Valette, a socialist and advocate for women’s rights and women’s education. Back in New York City, Elisabeth attended the prominent private school for girls that had been founded by philosopher and activist educator Ana C. Brackett and her partner Ida Eliot. This marked the end of Reid’s formal education, which would be significantly complemented by her extensive travels and advocacy in social work and the welfare of women.

Elisabeth followed in her father’s philanthropic footsteps and began by assisting with several of his enterprises. She was also a staunch supporter of the Episcopal Church’s missionary and charitable efforts, a loyal parishioner of the Church of the Reincarnation in New York, and also of the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. She had been confirmed at Holy Trinity in 1874, in the same class as artist John Singer Sargent, who was then living on the rue Notre-Dame des Champs in Montparnasse. Many years later, in 1912, Sargent drew her charcoal portrait. Reid remained a member of Holy Trinity for decades, endowing a pew in 1924, where she sat whenever she attended services in Paris.

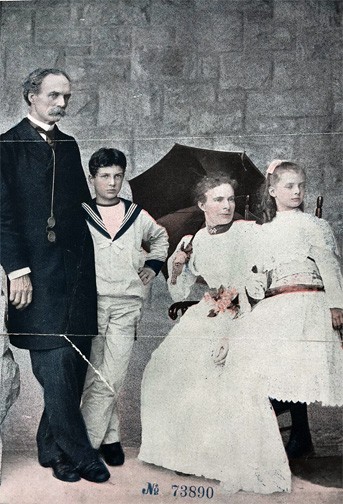

In 1881, Elisabeth Mills married Whitelaw Reid, twenty years her senior, a man described by some as “an introvert ‘who built around him a wall of reserve that repulsed familiarity’” (Zinsser 73). A newspaper man and astute politician, Whitelaw had relationships with many of the world’s most powerful political figures. The Reids had two children: Ogden and Jean, born in 1882 and 1884 respectively.

Elisabeth and Whitelaw formed the perfect combination of influence and success, and his thousands were complemented by her millions (The Sun). Magnificence and splendor characterized their lifestyle. As inveterate patrons of the arts, they accumulated a significant collection of works of art, which adorned their palatial residences, while Elisabeth embellished her fashionable wardrobe with precious jewels. Together, they were exemplary counterparts not only in taste and refinement, but also in action and sociability, developing a broad social network and "becoming true friends of many of the international elite" (Niemczyk). They were lauded for their grand parties, where the fashionable "who's who" interacted in gorgeous communion: diplomats and government officials mixed with self-made entrepreneurs, artists, writers, journalists, socialites, and philanthropists. One of Elisabeth’s many social triumphs was a ball she hosted in New York in 1919 for the Prince of Wales, with General Pershing and William Howard Taft among the guests (James 135).

When Whitelaw Reid was named ambassador to France in 1889, a position he held through 1892, Elisabeth renewed her many ties in the country she cherished. It was through Holy Trinity that she "[...] became deeply interested in the exposed condition of daughters of Uncle Sam, who came to study art [...] [and] had no chance for the right kind of companionship" (The Nashville Tennessean, August 15, 1909). Ever-committed to the arts, Elisabeth resolved to create a home where American women would find care, solace, and a happier social life. Her husband had supported the men’s American Art Association of Paris (AAAP), which had opened in 1890, and she hoped to establish a similar facility for American women. Through her network at Holy Trinity, she discovered the vacant property at 4 rue de Chevreuse, which had previously served as a boarding school for the young men enrolled at the Keller Institute. Elisabeth considered it an ideal location for women artists, at the heart of what was then known as the “American corner” of Montparnasse, which had long been the home of artists and art teachers. The immediate vicinity was replete with artist studios and art academies, including the Académies Julian, Colarossi, Vitti, and Delécluse. Painters and sculptors lived or worked steps away from the rue de Chevreuse, including John Singer Sargent, Paul Cézanne, William Bouguereau, James McNeill Whistler, Camille Claudel, Félix Gaudin, Paul Gauguin, Alphonse Mucha, and so many others.

Reid leased 4 rue de Chevreuse from the Keller family in 1893 with an "option to buy" the property in 1911 (which she did). She paid for significant upgrades to the buildings and, together with some American compatriots, formed a residential “Girl’s Art Club” that would provide cheap, but comfortable and congenial housing for young women artists. She insisted that the Club should be more than just another hostel – which could be found in many corners of Montparnasse. The Club’s mission was to foster an atmosphere in which sociability and hospitality ensured the integration of the residents into Parisian artistic networks and cultivated circles while shielding them from the bohemian demi-monde. Reid expanded the premises in 1911, purchasing the lot at the back where St. Luke’s Chapel had been erected by Holy Trinity in 1892. She also commissioned the American architect Charly Knight to design a third building with additional bedrooms and art studios, which would be connected to yet another structure for use as a large exhibition and meeting hall. She even erected a small medical clinic, which would treat American students in the Latin Quarter at no cost to them. With her support, the Girls' Art Club flourished until 1914, attracting a host of American women artists for whom it was a convenient center in which to work and from which to emanate. Especially important were the weekly afternoon teas that drew countless visitors, who appreciated the Club's tranquil atmosphere and conversational exchanges. For many of the budding artist-residents, the yearly exhibits of the American Woman’s Art Association, which was headquartered at the Club, also provided opportunities to showcase their skills and sell their work. All in all, the Club connected them not only with each other but also with the gatekeepers of the Parisian art world: gallery owners, art critics, and Salon organizers, most of whom were men.

In the chaos surrounding the outbreak of WWI, the Girls' Art Club, so long a haven for American women, hastily exiled its residents as disaster loomed. In 1914, Reid decided to transform the property into a military hospital serving the needs of the French and then the American Red Cross, who were caring for wounded officers. She underwrote the majority of the building modifications and new furnishings, and even rented apartments nearby to be used as storage spaces and accommodations for nurses and orderlies. The hospital housed doctors’ offices, nurses’ stations, an operating room, a sterilizing room, rooms and wards for recovering soldiers, a kitchen and dining room. Its courtyard and garden were, of course, quite a benediction for the patients and the staff. Reid continued financing a large part of this enterprise for the duration of the conflict, even after 1918, when 4 rue de Chevreuse became the administrative headquarters of the American Red Cross in Europe. For her contributions to the war effort, the French government named her Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1922.

When the Red Cross vacated the premises in 1922, Reid was approached by a number of institutions keen on claiming the space for their projects, but none were of interest to her. She initially intended to bring back the Girls' Art Club but changed her mind when she was presented with a compelling proposal from a group affiliated with women’s colleges in the United States. Spearheaded by Barnard's Dean Virginia Gildersleeve, who had just collaborated on the 1919 founding of the International Federation of University Women, this group included Bryn Mawr’s president and wealthy alumnae like Elizabeth’s daughter-in-law, Helen Rogers Reid. College-educated and aware of their potential as independent women, they formed a tightly-knit coterie of women’s rights advocates who were also involved in international peace movements. They had a utopian, feminist vision for a Club where debate, scholarly conversation in the sciences and humanities, and international cooperation would thrive. The group believed that opening a residential clubhouse for American women students and graduates in Paris would facilitate the needs of the growing number of women interested in French-American relations after WWI. It could serve as a convenient hub for conferences, enhancing the prospects for building networks of international university women. Importantly, the group proposed to alleviate Reid’s financial burden by raising funds through tuition and membership fees. Ultimately, they convinced Reid that university women should benefit from the privilege of a dedicated Parisian club that would also welcome female artists.

Thus, the American University Women’s Club was officially born in 1922.

Although the Red Cross had more or less returned the property to its original state, Reid financed further reconstruction and several embellishments necessary for the new Club. By 1928, the establishment was renamed Reid Hall in her honor. As in previous years, in 1929, Elisabeth funded the complete replacements of all the roofs and the renovation of the fourth floor of the historic building facing the rue de Chevreuse. She also paid for the complete overhaul of the “annex,” whose ground floor was transformed into a beautiful, wood-paneled dining room with adjoining kitchen and storage areas. A fourth story was added to that building, with new studios filled with natural light that could once again accommodate artists. In 1930, she again expanded the property by acquiring the passageway that led from the neighboring dwellings to the well in the first courtyard.

On the morning of April 29, 1931, Elisabeth died unexpectedly from double pneumonia at the age of 73, at the home of her daughter, Villa Rosemary in St. Jean-Cap-Ferrat. Elisabeth had sailed for France on April 14, after lending Ophir Hall to the State Department so it could welcome King Prajadhipok of Siam, his family, and his large entourage, who would arrive on April 22:

When the S.S. Leviathan docked at Cherbourg a fortnight ago, the most distinguished member of its passenger list [which included John J. Pershing and John Galsworthy] had contracted a slight cold. She was Mrs. Whitelaw Reid, who had just turned over her great Ophir Hall at Purchase, N. Y., to Siam's visiting King (Time, April 20 et seq.), had sailed away to spend her seventy-third spring in France (Time, May 11, 1931).

Walter E. Edge, U.S. Ambassador to France from 1929 – 1933, immediately lent tribute to Elisabeth Reid’s profound commitment to French-American relations:

Mrs. Reid’s death is an incalculable loss and the news of her passing comes to me, as it undoubtedly comes to her many friends, as a great blow […] Mrs. Reid was so brilliantly active, so devotedly helpful in the many foundations and charities which her enterprise and inspiration had made possible that, in spite of her advanced years, her friends were unprepared for the end. She was an unfaltering friend of France. Her deep sympathy for the French nation and appreciation of French culture dated back over half a century, and when her distinguished husband was minister in Paris in 1889-1892 she played an active part in making his mission a success. Reid Hall, where so many American students find hospitality, is but one monument of her unselfish devotion to and encouragement of practical Franco-American cooperation and friendship (New York Herald Tribune, April 30, 1931, 23).

Her memorial rites at the American Cathedral in Paris on May 7 attracted hundreds of people, including an impressive array of government officials, socialites, heads of American organizations in Paris, and 25 residents from the University Women's Club (Chicago Daily Tribune, May 8, 1931). The services were led by Dean Frederick W. Beekman and the Canons of St. Luke’s Chapel and the Cathedral. On May 30, 1931, the Overseas Service League dedicated a memorial elm tree to Elisabeth Mills Reid in their memorial grove in Central Park near 69th street.

Many articles appeared in the London, Paris, and New York press chronicling her life’s impressive work. A tribute, published anonymously in the Herald Tribune on May 11, 1931, describes the enormity of her philanthropic legacy in establishing Reid Hall:

The fact that so generous a series of benefactions, several decades of immense advantage to young American artists, to the Red Cross, to university women for more than half a hundred nations, can receive only passing notice in the vast number of selfless, wise gifts from a great woman, brings poignantly home the knowledge that 'there never was any one like her' […] Elisabeth Mills Reid, still a present power rather than a memory (14).

The article announcing her death in the New York Herald Tribune evoked her importance to Reid Hall:

Perhaps nowhere in France will Mrs. Reid's loss be felt more keenly or stir deeper regret than at Reid Hall, Montparnasse [...] Miss Dorothy Leet, director of Reid Hall, was deeply affected by the news and expressed the sorrow which every member of the American University Women's Club of Paris feels to be a personal loss in the passing of a woman who had been their close friend as well as their adviser and benefactor (April 30, 1931, 23).

In the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune, Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler described her passing as the end of an era:

I am profoundly shocked by the news. Before sailing for Europe only two weeks ago, Mrs. Reid seemed in such excellent health and spirits, and so full of plans for kindly service, both public and private, that it is almost impossible to think of her as having passed so quickly from the earth. Her death marks the end of an era here in New York. In every relation of life, whether unofficial or when Mrs. Reid was in high official posts, she had been a tower of strength and a central point for all that was best and most becoming in our social life and conduct (April 30, 1931, 3).

Reid's body, which had been transported to the home of her niece, the Countess of Granard (rue de Varennes) was returned to New York on May 9, 1931 via the RMS Mauretania, the passenger ship she had often boarded for her trips to France. She was accompanied by her daughter and son-in-law, and her private secretary, Miss Doris Goss, who later formed part of Mrs. Herbert Hoover's secretariat. Reid’s funeral was held at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on May 18, 1931, drawing over 2,000 friends, family members, government officials, and representatives of the various organizations she had supported. Among the copious flowers adorning the cathedral, there were wreaths from the King of Siam as well as from Herbert Hoover (New York Times, May 19, 1931). Reid was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York, at the side of her husband and family.

The most fitting appreciation of her spirit was published in The New York Times by an unknown admirer:

Mrs. Reid was a woman of large affairs, who dealt with them in a large way, ever aware of the responsibility of wealth and position. In London and here in New York she entertained on a lavish scale but without ostentation. By nature she was shy and remained to the last democratic in all her ways [...] Her social gifts combined with native modesty and an essential simplicity of character, enabled Mrs. Reid to meet the poet’s test of walking with kings without losing the common touch. She had a host of friends, of all ranks and stations in life, on both sides of the Atlantic, among young people as well as among men and women of her own generation. Many of them felt for her a respect and regard little short of veneration. She pursued her life steadily, and after her husband’s death, with indomitable resolution. In a day when society lost its mooring, and even its compass, she carried on the fine old tradition, as remote from the smart set as from the parvenu. To the end she took a lively interest about her, particularly in politics. Her philanthropies were legion, but never those of some distant patroness – any more than her interest in The Tribune was ever that of a mere absentee landlord. Whatever she did she did with her own will, with her own hand, and out of a full heart (April 30, 1931).

Following Elisabeth’s death, her daughter-in-law, Helen Rogers Reid, continued the family’s patronage for several more decades. By 1939, Reid Hall had evolved into a unique location for French-American intellectual exchange but its activities were once again halted by the onset of yet another World War. Following WWII, Reid Hall underwent yet another transformation, this time becoming a study-abroad venue for American universities and colleges from 1947-1964. To crown the family’s philanthropic efforts, Helen Rogers Reid secured the future of Reid Hall and the Reids’ legacy by gifting the property to Columbia University in 1964, with the proviso that it would pursue and diversify Reid Hall’s mission as a center for pedagogy, research, and public programming.

As a woman of wealth and prominence, Elisabeth paved the way for thousands with the educational opportunities she supported. Because of her, many followed suit, contributing to Reid Hall’s activities with smaller donations, endowments, and fellowships; some simply, yet no less generously, gave of their time and creative energy. Because of her, 4 rue de Chevreuse was able to attract women thought leaders, artists, activists, educators, and administrators who worked, spoke, or created within its walls. Much of their history remains unwritten, but they were doubtless “movers and shakers willing to cross borders,” women who were not “passive creations of history and institutions” but “active creators who forged parallel power structures.” (....) source???

Sources

- “A Notable Career: The Scope of Mrs. Reid’s Activities World-Wide.” The New York Times, April 30, 1931, p. 23. Timesmachine.

- Allen, Cameron. The History of the American Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Trinity 1815-1980). Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2013.

- Ambassador Edge Voices Grief at Mrs. Reid's Death." New York Herald Tribune, April 30, 1931, p. 23 ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Andrews, Maude. "Maude Andrews in Paris: Reception in Honor of the Wives of the Peace Commissioners..." The Atlanta Constitution, January 22, 1899, p. 6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Art to be Auctioned at Noted Residence.” The New York Times, April 24, 1934, p. 21. Timesmachine.

- “Body of Mrs. Reid Here on Mauretania.” The New York Times, May 16, 1931, p. 22. Timesmachine.

- Comment in Editorials on Death of Mrs. Reid: Press Voices Tribute to Career and Influence she Exerted." New York Herald Tribune, May 1, 1931, p. 23. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Cowles, Kilbourne. "American Girl Students in Paris.” The Advance, April 1, 1909, vol. 57, no. 2266, p. 404. ProQuest

- “Death of a Great Lady” Time, vol. 17, number 19, May 11, 1931, p. 14.

- “Defrays Expenses of Twelve Nurses.” The New York Times, August 9, 1914, p. 4. Timesmachine.

- Dock, Lavina L. et al. History of American Red Cross Nursing. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922.

- "Elisabeth Mills (Mrs. Whitelaw) Reid 1858–1931." American Journal of Nursing, vol. 31, no. 6, June 1931, pp. 716-717.

- Elizabeth Whitelaw Reid Club of Islington.

- “Farewell Banquet to the Hon. Whitelaw Reid.” The American Register for Paris and the Continent, March 26, 1892, vol. 24, no. 1251, p. 6. Gallica.

- “Friends in London Unite in Tribute to Mrs. Reid.” The New York Herald European edition, April 30, 1931, p. 3. Gale Primary Sources International Herald Tribune Archive, 1887-2013.

- “Friends at Home and Abroad Pay Glowing Tribute.” The New York Herald European edition, April 30, 1931, p. 1, 3. Gale Primary Sources International Herald Tribune Archive, 1887-2013.

- “General Pershing Sails on Ship to France.” The New York Times. April 16, 1931, p. 52. Timesmachine.

- “Generosity of Mrs. Whitelaw Reid: In Establishing a Club for Women.” The Nashville American, Aug 15, 1909, p. A6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Gives Roosevelt Tablet.” The New York Times, October 15, 1919, p. 21. Timesmachine.

- "Growing Importance of American Red Cross Work in Great Britain." Red Cross Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 34, August 19, 1918, p. 8. HathiTrust.

- Historic Saranac Lake Wiki

- “Hoover Lauds Mrs. Reid.” The New York Times, April 30, 1931, p. 23. Timesmachine.

- James, Edward, T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, “Reid, Elisabeth Mills.” Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, volume 3. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971, pp. 134-135.

- “King Was Bored at Royal Court.” The New York Times, March 7, 1909, p. 21. Timesmachine.

- “Lettres d’Amérique.” Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, April 10, 1889, p.2. Gallica.

- “Many Are Present at Services for Mrs. Whitelaw Reid.” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 8, 1931, p. 3. Gallica.

- “Miss Anna C. Brackett Dead.” The New York Times, March 19, 1911, p. 11. Timesmachine.

- “Mrs. Reid Honored by Memorial Tree.” The New York Times, May 31, 1931, p. 16. Timesmachine.

- Mrs. Reid, 73, Dies on Trip to France." The Hartford Courant, April 30, 1931, p. 13. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Mrs. Reid Rests at Her Madison Avenue Home." New York Herald Tribune, May 16, 1931, p. 19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Mrs. Reid’s Estate Totals $18,589,916.” The New York Times, May 26, 1934. p. 6. Timesmachine.

- “Mrs. Reid’s Life Exemplified a Career Devoted to Others.” The New York Herald European edition, April 30, 1931, p. 3. Gale Primary Sources International Herald Tribune Archive, 1887-2013.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid.” Town & Country, vol. 61, no. 11, May 19, 1906, p. 19. ProQuest.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid.” The New York Times, April 30, 1931, p. 22. Timesmachine.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid Appointed.” Red Cross Bulletin, vol. 1, no. 32, December 10, 1917, p. 73. HathiTrust.

- "Mrs. Whitelaw Reid Dies of Pneumonia while on Visit to the Riviera." New York Herald Tribune, April 30, 1931, pp. 1, 23. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid Is Dead in France.” The New York Times, April 30, 1931, p. 23. Timesmachine.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid Is Ill.” The New York Times, April 29, 1931, p. 22. Timesmachine.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid Receives Cross of Legion of Honor.” The New York Times, July 19, 1922, p. 11.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid’s Ball.” The New York Herald European Edition, May 29, 1890, p. 1. Gallica.

- “Mrs. Whitelaw Reid’s Will Creating Large Trusts.” The New York Times, May 22, 1931, p. 18. Timesmachine.

- Niemczyk, Caroline. “Elisabeth Mills Reid and Helen Rogers Reid: The Founder and Perpetuator of Reid Hall, 1893 – 1964.” Paper presented at the Centennial Celebration held at Reid Hall in June 1993. Manuscript, Reid Hall archives.

- “Notables Attend Mrs. Reid’s Funeral,” The New York Times, May 19, 1931, p. 26. Timesmachine.

- “Ogden Mills Dies at his Home Here.” The New York Times, January 29, 1929, p. 8. Timesmachine.

- One of the Obscure. “Memories of a Paris House.” New York Herald Tribune, May 11, 1931, p. 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Oversea League Dedicates Six Memorial Elms: Tribute to Mrs. Whitelaw Reid." New York Herald Tribune, May 31, 1931, p. 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Peninsula Royalty: The Founding Families of Burlingame-Hillsborough.

- “Publishers Eulogize Mrs. Whitelaw Reid.” The New York Times, May 9, 1931, p. 13. Timesmachine.

- “Reid Art Yields $155,897 at Auction.” The New York Times, May 4, 1945, p. 19. Timesmachine.

- Reid, Elisabeth Mills, et al. Reid family papers, 1795-2003, Library of Congress.

- “Reid Hall Here Says Memorial to Its Founder.” The New York Herald European edition, April 30, 1931, p. 3. Reid Hall archives.

- “Reid House Dedicated.” The New York Times, August 29, 1930, p. 13. Timesmachine.

- “Reid – Mills. Dr. Morgan Conducts the Ceremony at Mr. D. O. Mill’s House.” The New York Times, April 27, 1881, p. 5. Timesmachine.

- “Reid Takes Wrest Park.” The New York Times, August 17, 1905, p. 3. Timesmachine.

- Republican Party Presidential Ticket, 1892.

- Services Held at the Cathedral for Mrs. Reid: Many Friends Present." New York Herald Tribune, May 19, 1931, p. 25. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Siamese King Takes a Westchester Home.” The New York Times, November 8, 1930, p. 19. Timesmachine.

- "Simple Service for Mrs. Reid in Paris Church." The New York Herald Tribune, May 8, 1931, p. 23. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Son and Daughter Get Mills Millions.” The New York Times, January 18, 1910, p. 4. Timesmachine.

- “300 at Reid Sale Buy $81,145 Art.” The New York Times, May 3, 1934, p. 31. Timesmachine.

- Thurmond, Aubri, E. “Under Two Flags: Rapprochement And The American Hospital Ship Maine,” M.A. Thesis, Texas Women’s University, Denton, Texas, December 2014.

- “What is Doing in Society.” The New York Times, October 18, 1902, p. 9. Timesmachine.

- "Will Serve Mrs. Hoover: Miss Doris Goss, Former Secretary to Mrs. Reid, is in Washington." New York Times, October 23, 1931, p. 27. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Women Send Gifts to Cathedral Fund.” The New York Times, March 4, 1925, p. 12. Timesmachine.

- Zinsser, William, “The Paper: The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune by Richard Kluger (Book Review).” Columbia Journalism Review, Nov 1, 1986, vol. 25, no.4, p. 73. ProQuest