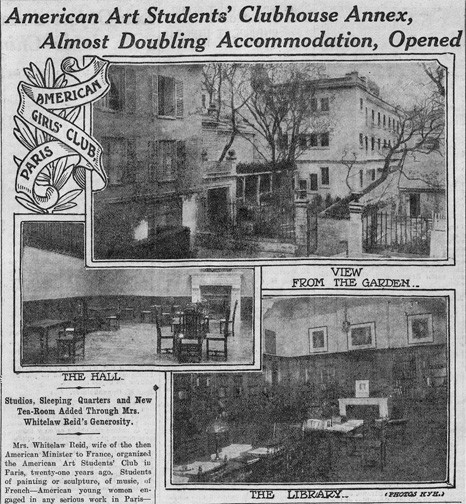

Property Improvements, 1911 – 1912

When Elisabeth Mills Reid leased the property at 4 rue de Chevreuse in 1893, she restored and furnished the interior spaces for her new American Girls' Art Club. In the early years, the Club still maintained the outdoor gym, which had been inherited by the previous tenant, Jean-Jacques Keller, from an orthopedic clinic that had occupied the property in the 1820s. The gym is described in an 1896 article as being "attached" to the Club, along with a restaurant and picture gallery (Leisure Hour 334).

The Club had become so popular by 1911 that Elisabeth Mills Reid decided to expand the property. She envisioned new art studios, more dormitory quarters, and the addition of a large space for exhibitions and meetings. In 1913, Reid finalized the purchase of the property she had been renting from the Keller family for twenty years. Sadly, the women art students only enjoyed the sparkling new facilities for one year before World War I closed the Club for good.

The Architect

The new building abutting the rue de la Grande Chaumière was designed by American architect Charles Meissonier Knight, known as Charly Knight, born in Poissy, France on November 27, 1877. His father, Daniel Ridgway Knight, was a celebrated painter who spent most of his life in France and worked in the private studio of Ernest Meissonier (after whom Charly was named). Charly’s brother, Louis Aston Knight, was a well-respected landscape artist. Educated at the Lycée Condorcet, then at the École des Beaux-Arts, Charly married Alice Boucherie, daughter of Maurice Boucherie, inventor of a wood conservation method on August 12, 1903 (Knight 8). In 1905, he was awarded a "mention honorable" in architecture at the Salon des artistes français. Like Reid, Knight was affiliated with the Church of the Holy Trinity. He was very popular in the American colony, receiving prestigious commissions for grand buildings and private homes. In 1913, he was invited to become a permanent member of the reputable Cercle de l’Union artistique and was made Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1924. His office at 11 rue Marbeuf in Paris was described in the Paris Times as "[...] furnished with antiques of beautiful workmanship and tapestries of an older day. His working quarters indicate an artistic heritage confirmed by his parentage and life" (4). During WWII, Knight may have been interned in the German "international" camp in Compiègne. He died on January 13, 1967 and was buried in the cemetery of St. Germain en Laye.

Knight’s monumental art, private residences, and public architecture are impressive. Several of his buildings are cataloged in L’Inventaire général du patrimoine culturel. Notable examples of his work include:

War memorial by Knight and sculptor Marius Borget, inaugurated in Peyrieu, France on November 23, 1919. Patch, p. 313.

View of the Memorial Hospital Construction Site. The Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1925, p. 4.

Interior of Tiffany & Cie, rue de la Paix, 1910. Phillips p. 43.

Ford Factory Building, Asnières, built between 1925 and 1929. Jantzen, p. 42.

Charly Knight, director's House, Ford factory, Asnières, 1928. Jantzen, p. 42.

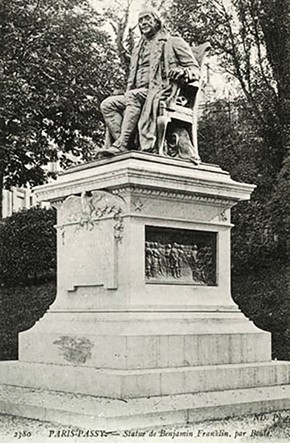

- c. 1905 – 1906: Pedestal for John-J. Boyle’s statue of Benjamin Franklin, donated to the city of Paris by the financier John-H. Harjes and unveiled on April 20, 1906 in the Trocadero gardens. The massive pedestal featured bas-reliefs by Frédéric Bron and also depicted an extract of Mirabeau’s 1790 eulogy of Franklin: “The genius who freed America and poured a flood of light over Europe! The sage whom two worlds claim as their own” (Le Figaro, March 30, 1906, 3, translated from French).

- c. 1908 – 1910: Tiffany & Cie. Collaborating with interior decorator Armand-Albert Rateau, Knight designed Tiffany’s 360-meter-square boutique on the fashionable corner of rue de la Paix and place de l’Opéra (Phillips 42).

- 1915: Redesigned the private homes of American author Edith Wharton, transforming her house at St.-Brice-la Forêt as well her villa at Hyères.

- 1918 – 1919: Sources indicate that he renovated the château de Peyrieu, the home of Mr. and Mrs. John Jacob (Grace Whitney) Hoff near Aix-les-Bains.

- 1919 In collaboration with sculptor Marius Borget, Knight designed a Cenotaph that was publicly revealed on November 23.

- 1920: Restored and modernized the entire interior of the eighteenth-century building occupied by the Bankers’ Trust, place Vedôme.

- 1922 – 1926: Designed the American Hospital’s Memorial building in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France.

- 1925 – 1929: Designed the Ford automobile factory and director’s residence. Asnières, France.

- 1926 – 1928: Designed the Foyer international des étudiantes, 93 Boulevard St. Michel. This residence had been founded in an old convent in 1906 by Grace Whitney-Hoff, member of Holy Trinity. Hoff commissioned Knight to completely renovate the property, creating seven distinct floors, with a beautiful wood-paneled library, rooms for 100 residents, a cafeteria, salons, concert hall, and an infirmary. It was opened on October 10, 1928. Whitney-Hoff donated the property to the University of Paris in 1936.

- 1933: Created the Renault showroom (now the Citroen showroom), Avenue Wagram, one of the best examples of industrial design in its time.

Charly Knight, pedestal of statue of Benjamin Franklin, Trocadero, 16th arrondissement, Paris. E-monumen.

Library of the Foyer International des étudiantes, 2021. Photograph by B. Biebuyck

The Annex

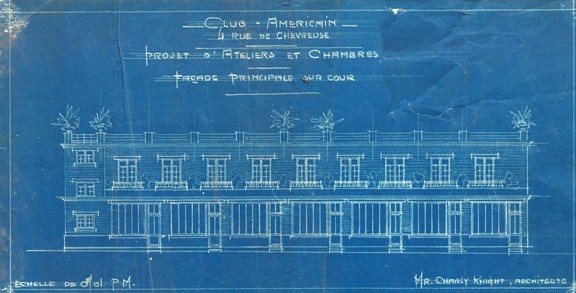

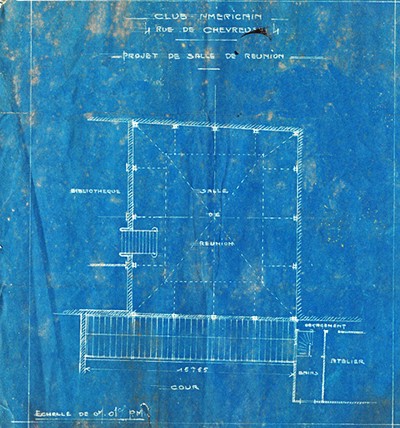

Charly Knight, blueprint for the Annex. RH Archives

Originally, Knight designed a two-story building abutting the rue de la Grande Chaumière (referred to as the Annex) with studios on the ground floor and student bedrooms above. By the time the structure was completed in 1912, a third story had been added. In its finished state, the brick building included 20 bedrooms, seven private art studios, one club studio, and a rooftop terrace. The architecture is a fine example of the Neo-Renaissance style in France of which Knight was one of the early proponents.

The French newspaper, L'Intransigeant positively reviewed the new edifice:

We have often said that Paris was a paradise for foreigners, and we are not wrong when we think of all the things we have done for them. But they also do many things for themselves – and for us… Many Parisians know the rue de la Grande-Chaumière, steps away from the Luxembourg gardens, where the majority of art studios on the Left Bank were situated. An architect of good taste, M. Charly Knight, has built on this street, near the small English chapel, a complex of buildings, comprising studios and residences, destined only for American women who have come to study in Paris. M. Charly Knight managed to combine in a charming manner the comforts of English style with the charm of an old French garden, which he preserved. The buildings are organized in such a way that passersby can see a bit of gay greenery from the street. Imagine what would have happened had he built a revenue house. It is somewhat ironic that foreigners – in this case the Club for young American women of the rue de Chevreuse – come to kindly give us wise lessons on the way in which we arrange our Paris (translated from French, 2)

Salle d'Exposition

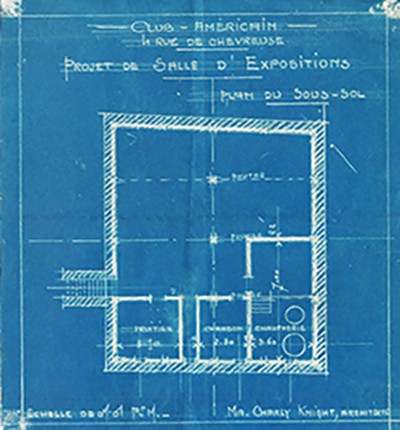

Charly Knight, blueprint for the basement below the Salle d'Exposition. RH Archives

Charly Knight, blueprint for the Salle d'Exposition. RH Archives

Knight was also responsible for designing a separate structure, the present-day Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc, located between the eighteenth-century rue de Chevreuse building and his new building. This structure was conceived as a tea and music room, exhibition space, and lecture hall, which could be accessed through the old Chevreuse building.

A double-height monumental space, it was decorated with wood-paneling, covered with a glass ceiling and pyramidal skylight, and outfitted with electrical lighting for evening ambiance. Adjoining it was the furniture depot, above which exhibitions and receptions were held.

Knight also redesigned the room above, converting it into a handsome wood-paneled library with French doors that overlook the Grande Salle.

The Clinic

At Reid’s request, a small wood pavilion was added in the garden ca. 1911-1912 to serve as a medical clinic for American students in Paris. The clinic was managed by an American nurse, and an American doctor based in Paris generously offered medical advice to the students. After the American Hospital opened, their doctors and nurses continued to serve the community at this clinic.

Sources

- "$300,000 Goal in Intensive Campaign for American Hospital This Week." Chicago Tribune and The Daily News, New York, June 20, 1925, p. 4. Gallica.

- “American Art Students’ Club House Annex, Almost Doubling Accommodation, Opened.” The New York Herald European edition, November 3, 1912, p. 6. Gallica.

- “Cercles.” Le Figaro, June 12, 1913, p. 3. Gallica.

- “Echos.” Le XIXè Siècle, August 13, 1903, n.p. Gallica.

- “En L’honneur de Benjamin Franklin.” Le Figaro, March 30, 1906, p. 3. Gallica.

- Hampton, Ellen. "Room for Education: The Philanthropy of Grace Whitney Hoff." Trinité, vol. 15, no.1, Spring 2020, pp. 24-25.

- "Hospital is Model." Chicago Tribune and The Daily News, New York, June 22, 1927, p. 7. Gallica.

- Jantzen, Hélène, 1860-1960, Cent ans de patrimoine industriel dans les Hauts de Seine. Inventaire générale des monuments et des richesses artistiques de la France. Lieux Dits Editions, 1997.

- "Knight." E-Monumen.

- Knight, Charly. “La conservation des bois.” Navigazette, March 11, 1909, pp. 7-8. Gallica.

- L. “La Statue de Franklin.” Le Journal, April 28, 1906, p. 3. Gallica.

- “La vie feminine.” Le Figaro, July 6, 1930, p.5. Gallica.

- “Le Monument Benjamin-Franklin.” Le Petit Journal, December 29, 1905, p. 3. Gallica.

- “Les recompenses du Salon des artistes français.” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, June 3, 1905, p. 172. Gallica.

- Malardot, Paule, “La Femme seule à Paris: Foyer international des étudiantes.” Les Dimanches de la femme: supplément de la "Mode du jour,“ January 25, 1931, p.15.

- “Nos Échos.” L’intransigeant, September 13, 1912, p. 2. Gallica.

- Patch, Carolyn. Grace Whitney Hoff: The Story of an Abundant Life. Cambridge, MA: Privately printed at the Riverside Press, 1933.

- Phillips, Clare, ed. Bejewelled by Tiffany, 1837-1987. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Stevens, William. "Homes and Clubs for Women in Paris." The Leisure Hour, March 1896, pp. 331-334. British Periodicals Collection I.

- “The Man of the Day.” The Paris Times, May 16, 1926, p. 4. Gallica.

- “Who’s Who Abroad” Chicago Tribune and The Daily News, New York, February 4, 1926, p. 4. Gallica.