Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877 – 1968

Born in 1877 into a middle-class Black family in Philadelphia, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller expressed an early interest in the arts and won a scholarship to study at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art in 1894: "At her graduation from that school five years late, she was awarded a first prize for her metal crucifix of a tormented Christ and an honorable mention for a clay model she called Procession of Arts and Crafts." (Lewis 53). At the age of 22, she traveled to Paris, immersing herself in the international art scene at its peak. She studied and exhibited in Paris from 1899 to 1902.

Before leaving Philadelphia, Fuller had written to Julia Acly, the director of the American Girls' Art Club, who promised her one of its available thirty-eight rooms. Henry Ossawa Tanner, a family friend and noted Black artist in Paris, was going to meet her at the train station when she arrived. Unfortunately, from the outset, Fuller encountered many difficulties. Tanner missed her at the station and she was forced to travel to the Club alone. Upon arriving at 4 rue de Chevreuse, Acly met her with shock and resistance: "You didn't tell me that you were not a white girl?" (Kerr 74). Acly then explained that Fuller would not be able to reside at the Club, confessing that she was afraid the other women, especially those from the American South, would mistreat her. Fuller's own account of her first meeting with Acly reflects her dignity and composure in the face of blatant racism. In response to Acly's question about why Fuller had not identified her race before arriving at the Club, she apparently replied, "I was told that the American Girls' Club was financed by Mrs. Whitelaw Reid and other American women [...] and it was here for the American girl students who came to Paris to study. I felt that I, as an American girl, was entitled to come here" (as quoted in Ater 15-16).

When Tanner finally found Fuller later that day, he encouraged her to find alternate accommodations since the Club was a “cliquey place” (Kerr 76). Acly assisted her in finding a room but it didn’t suit her needs so Fuller found herself moving in and out of several hotels and apartments before settling down.

It comes as no surprise that Fuller was denied a room at the Girls' Art Club given that exclusion and the poor treatment of Black people was endemic at the turn of the twentieth century. The Girls' Art Club was by no means the only institution in Paris that operated with prejudice.

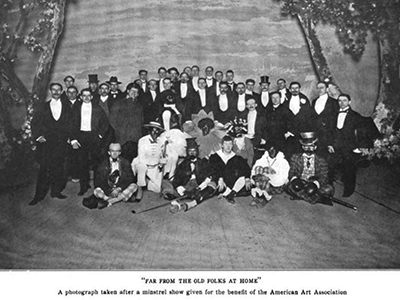

Henry Ossawa Tanner, who had already established himself as an artist in Paris by the time Fuller arrived, was an accepted member of the American Art Association of Paris (AAAP), the male equivalent of the Girls' Art Club. Perhaps this was because the AAAP's clubhouse was merely a social headquarters and not a residence where White artists would have had to live closely with their Black colleagues.

The photo on the left ca.1907 of a minstrel show given at a benefit to raise money for the Association is quite telling. Blackface is recognized as racist and unacceptable in the twenty-first century, but it was widely prevalent and popular at the time. One can imagine how unsettling it was for Tanner, Fuller, and their peers to bear witness to such stereotypically racist depictions. This extra stress would have compounded the challenges and homesickness they had to face as they pursued their artistic development.

Even when the American press was praising Fuller's skill as an artist, it was racially tinged (and not at all accurate). The article, "American Women Who Have Won Fame as Sculptors," appeared in the Chicago Sunday Tribune on June 21, 1903, and featured Meta Fuller. On the one hand, "She is the sculptor whose masterly expression of strange and original thought led Rodin – the celebrated, unique Rodin – to give her his special attention and a great deal of his valuable time during the three years of study she spent in Paris." But, she is also "the Philadelphia mulatto girl" who somehow managed to bring one of her sculpted models to Rodin at the age of 10 to become his protege (not at all true). The Tribune article describes the work of five other American women sculptors, all White, but none are portrayed with the kind of back-handed compliments reserved for Fuller (46).

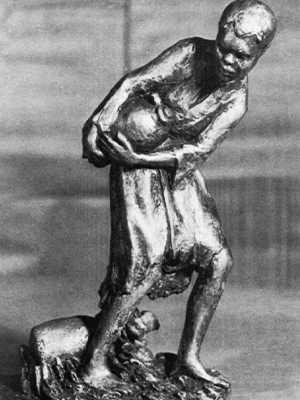

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, "The Wretched," 1902, bronze. Maryhill Museum of Art. She exhibited this evocative work at the 1903 Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts and it was praised by the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Though Fuller's perseverance and adaptability shone through when the Club rejected her, the broader impact of her exclusion meant that "she was unable to participate in the lively interchange among residents at the club: the informal sketch classes, the collegiality and support of other American women artists, and the formal entertainments that involved well-known artists and dealers" (Ater 23).

A contemporary account from someone identified only as "CFM" published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1901 describes the cruelty and hypocrisy of her White peers in their treatment of Fuller. CFM, whom we have identified as Club artist and resident Cornelia Field Maury, does not specifically name any women but she does reference an encounter with Henry Ossawa Tanner, leaving no doubt that the incident she described at 4 rue de Chevreuse involved Meta Fuller. We have not yet uncovered the identity of the primary instigator from South Carolina but perhaps new evidence will come to light. For the sake of readability, the entire article is transcribed below:

I am obliged to President Roosevelt for setting the American people such a good example and bringing the color question to the surface once more for solution. We as a nation have to settle it some time, and the oftener it comes up the sooner it will be over. The injustices we white people, as a class, deal out to the colored is astounding in a supposedly liberty loving land, when calmly considered. It seems to be so universal as to make one ashamed of one’s country. I have personal knowledge of such treatment to colored people who are as refined, well-educated and moral as my own white friends. At dinner one evening in Paris, I had the honor of meeting the eminent American painter, Mr. Henry O. Tanner, a man who stands with the best in his profession, reflecting great distinction on his country. In manner and conversation, he was the educated gentleman. I did not find myself hurt in the least by the acquaintance, but honored. It is well understood why Mr. Tanner prefers to live in Paris rather than in the United States. He knows as well as most of us that he would be so cordially snubbed almost everywhere that life here would be impossible today.The case of Miss –––, a colored girl at the American Girls’ Club in Paris, is another instance of man’s inhumanity to man, though here woman’s inhumanity to woman. This girl from Philadelphia went to study art as hundreds of other American girls do, bringing good letters, and expected a home at the club. She got board and room there, but when a certain young woman from South Carolina found herself eating breakfast in the same dining room with the colored girl she threatened to leave the club, and Miss ––– was politely asked to go elsewhere. For one year nearly I saw Miss ––– frequently at the club – she was allowed all other privileges of the place – and I know that she was the object of unjust criticism and many a cool snubbing of which she was perfectly conscious, but never openly resented. She couldn’t: there were too many against her. And this was done by both northern and southern young women. One could see that she was equal in breeding, education, ideas of dress and politeness to the nicest girls there, but her one sin was the tint of her skin. It would be hard for humanity if God drew the color line across the souls of his children. Yet these same superior Americans, the South Carolinian, too, went to the little Episcopal chapel in the court every Sunday and thought they were Christians. It seems queer! All Americans would do well to read Booker Washington’s “Up From Slavery” and “Autobiography.” The colored man demands only what every American claims for himself – equal rights, common justice. So, judge the negro as we judge ourselves – by individual merit. Give them equal chances, commercially and industrially: open the college doors to him and the club doors, and, if need be, break bread with him. If you are a man, a real man, it will be all right; but if you are a little man, you’ll fall. C. F. M. St. Louis.

Fuller was undaunted and determined. She struck out on her own, developing a network of friends and mentors, and her inauspicious beginnings at the Girls' Art Club were later offset by gratifying experiences in various académies. Initially, Julia Acly had introduced her to the American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who urged Fuller to take drawing lessons before embarking on sculpting, suggesting William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Raphaël Collin as possible teachers. Fuller enrolled in Collin's atelier, which proved to be very expensive and ultimately dissatisfying. At the urging of a friend, she then began working under the tutelage of sculptor Jean-Antonin Carlès. Fuller also joined classes at the Académie Colarossi and studied drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts. One of her classmates, Paula Modersohn-Becker, asked Clara Westhoff Rilke to introduce Fuller to Auguste Rodin. When Fuller traveled to his Meudon studio in the summer of 1901, he immediately recognized her talent: "My child, you are a born sculptor, you have a sense for form" (quoted in French in Kerr, 3). Rodin subsequently took her under his wing (Leininger-Miller 9).

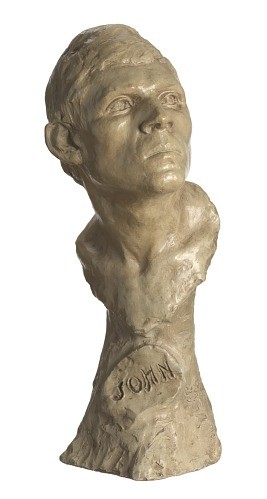

Tanner, who served as one of the judges for the annual exhibition of the American Woman's Art Association, encouraged her to exhibit one of her pieces at its 1902 show: "At the very hostel that had refused her board, Fuller’s bust, John the Baptist (c. 1901), was displayed and it was also reproduced in the Herald Tribune Paris edition." The newspaper reported that Fuller had “the distinction of being the only sculptor represented” (Leininger-Miller 9).

Fuller's career flourished. After the exhibit at the Club, Siegfried Bing sponsored her one-woman show at his gallery, La Maison de l'Art Nouveau, that same year. She also exhibited two of her works in the prestigious 1903 Salon des Beaux Arts, "The Wretched," and "The Impenitent Thief." Bolstered by this recognition, she returned to the United States in 1903.

In 1907, Fuller was the first artist to be commissioned by the U.S. government to do a series of dioramas on the history of African Americans (Lewis). She exhibited them at the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia (1907), and won a gold medal for her work:

In Landing and thirteen other dioramas, she used more than 130 painted plaster figures, model landscapes, and backgrounds to give viewers a chronological survey of the African American experience. Scenes ranged from a tableau of a fugitive slave to a depiction of the home life of "the modern, successfully educated, and progressive Negro" [...] Warrick's dioramas, [...] enabled blacks to see themselves as the main actors in their own defined world. Whereas "Old South" concessions and anthropological exhibits organized by whites exhibited blacks, Warrick's dioramas represented them. The distinction between exhibiting and representing blacks was not just authorship but also agency (Brundage 1368, 1371).

None of the dioramas still exist, but images can be found through The New York Public Library's Digital Collections.

A warehouse fire in 1910 destroyed Fuller’s belongings, including sixteen years' worth of work. The loss was devastating but she continued to sculpt, even though her husband, the Liberian-born neurologist Solomon C. Fuller (whom she married in 1909 and who practiced at the Massachusetts State Hospital), opposed her working as an artist. They lived in Framingham, Massachusetts and had three children.

Against all odds, Fuller pursued her artistic career for over sixty years, aided by a long-standing friendship with W.E.B. Du Bois, whom she had met in Paris. According to Du Bois, along with her undeniable talents, "'the accidents of education and opportunity have raised [Fuller] on the tidal wave of chance'" (Kerr vi). The legacy of Fuller's unflinching depictions of Black life and her relationships to many of the key players in the Harlem Renaissance make her one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century.

Meta Warrick Fuller died on March 18, 1968 at the age of ninety-one. On October 15, 1999, her son, Solomon C. Fuller, Jr., presented West Virginia State College, where his mother had lectured in the late 1950s, with a sculpture he re-titled "Ravages of War" – the 1917 sculpture had been originally titled "Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War ("'Ravages of War' unveiling at WVSC").

The Danforth Museum in Framingham is the "caretaker of the Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller Special Collection. This collection consists of ephemera, process pieces, studies, and other objects of art that expand upon some of the better-known aspects of Fuller’s oeuvre." Her papers are housed at the Schomburg Center of the New York Public Library.

Sources

- "American Women Who Have Won Fame as Sculptors." Chicago Sunday Tribune, June 21, 1903, p. 46. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Ater, Renée. Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. "Meta Warrick's 1907 'Negro Tableaux' and (Re) Presenting African American Historical Memory." The Journal of American History, vol. 89, no. 4, March 2003, pp. 1368-1400. JSTOR.

- CFM. "Another View of Negro Equality." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 30, 1901, p.4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Hoover, Velma J. “Meta Warrick Fuller: Her Life and Art.” Negro History Bulletin, volume 40, no. 2, March-April 1977, pp. 678-681.

- Kennedy, Harriet Forte. "An Independent Woman: The Life and Art of Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968)." Framingham, MA: Danforth Museum of Art, 1984.

- Kerr, Judith Nina. "God-Given Work: The Life and Times of Sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877- 1968." PhD Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, 1986.

- Leininger-Miller, Theresa A. New Negro Artists in Paris: African American Painters and Sculptors in the City of Light, 1922-1934. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

- Lewis, Samella. Art: African American, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., 1978, see, pp. 53-55.

- Lewis, Femi. “Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller: Visual Artist of the Harlem Renaissance.” ThoughtCo. October 27, 2019.

- Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller Special Collection. Danforth Museum, Framingham, Massachusetts.

- Meta Warrick Fuller Papers, 1864-1990. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY. New York Public Library archives.

- "'Ravages of War' unveiling at WVSC." The Charleston Gazette, October 7, 1999, p. 10. ProQuest Documents.