Cornelia Field Maury, 1866 – 1942

Cornelia Field Maury was born in New Orleans but spent much of her life in St. Louis, Missouri. She never married and was able to pursue a career as a professional artist thanks to her family's financial support. Studying first at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts at Washington University, Maury twice traveled to Paris to continue her training: at the Académie Julian with J.P. Laurens, Benjamin Constant, and Jules Joseph Lefebvre from 1890-1891, and at the Académie Vitti with Raphael Collin and Olivier-Luc Merson in 1899. Though she is not as widely remembered as her contemporaries Mary Cassatt (with whom she corresponded), Cecilia Beaux, and Elizabeth Nourse, Maury was well-known in her era. She contributed an illustration to The Woman Citizen, an early suffragist publication; another illustration appeared in W.E.B. DuBois' The Crisis, the first official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (Tillinger 3).

The American Girls' Art Club did not exist when Maury first visited Paris but when she returned in 1899, having sailed across the Atlantic on the S.S. Columbia, she lived at 4 rue de Chevreuse. Letters from Maury to her mother documented her life in Paris, including her intense loneliness and the high cost of meals outside the Club. Her former St. Louis classmate, Mary Fairchild MacMonnies, also exhibited at the Club and served as president of the American Woman's Art Association. Letters from fellow art students in Paris, Florence Morse and Anna Sheddon Dodge, tell us that Maury studied under Olivier-Luc Merson in an atelier at the Académie Vitti, located on the Boulevard du Montparnasse. She also visited the popular summer artists’ colony in Laren, Holland in August 1900 (Tillinger 212).

While in Paris, Maury bore witness to one of the ugliest incidents in the history of the Girls' Art Club: the social exclusion of African American sculptor Meta Fuller, who had planned to live at the Club but was denied a room because of the color of her skin. Maury was disgusted by the cruelty and hypocrisy of her fellow art students, particularly since so many of them identified as Christians and regularly attended religious services at St. Luke's Chapel. She described this incident and the unfair treatment of Fuller in a letter to the editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published on October 30, 1901 (4).

Maury was a prolific exhibitor, with her earliest public showing in 1887 when she was just 21 years old, and her last exhibition in 1942, close to the time of her death. Her work appeared in the Salon des artistes français of 1900 (the drawing "Mother and Child" was hung on the line). In the 20th century, she exhibited frequently in her beloved St. Louis. Another friend and correspondent of Maury's was the acclaimed writer Kate Chopin, whose work captured the lives and inner worlds of 19th-century Southern women. A letter from Chopin to Maury was published along with Chopin's other private papers. On December 3, 1895, Chopin wrote: "I have received your kind invitation to attend the exhibition of Water Colors, and shall take much pleasure in doing so. I hope to look into your Studio some afternoon before long, if you will let me" (208).

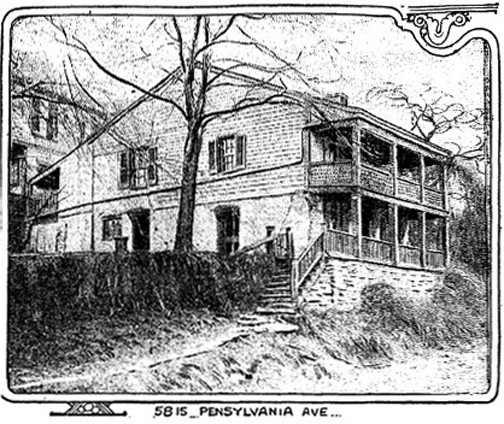

Maury made St. Louis headlines in 1913 when she fought the city's proposal to destroy or move her family's landmarked home in order to make room for a new street. According to The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the home was at least 135 years old (meaning it had been built in the 18th century during French occupation), and Charles Dickens had been entertained there in 1844 during a visit to the city. She was quoted in the paper on April 6, 1913: "There is absolutely nothing of the sentimental in my opposition to the ordinance [...] I do not want the old home unaltered just because it is an old home, but as an artist I can see the value of the landmark as a point of interest for sightseers" (A1B). Though she did not succeed (the house was moved to a new location), her fears about damage to the structure luckily did not come to fruition.

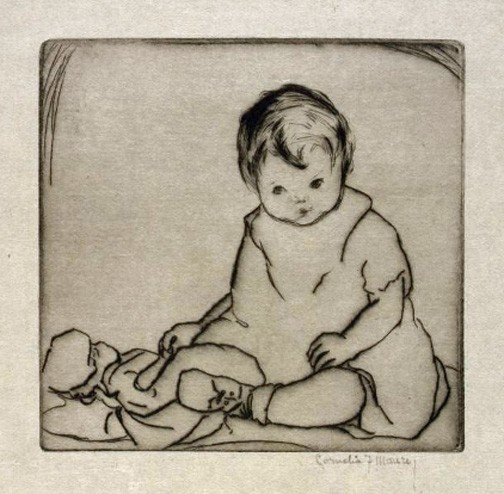

Working mostly in watercolors and pastels, Maury also experimented with oils later in life, though her subject matter, depictions of children, babies, and some landscapes, remained constant (Waters 232). Her 1905 painting, "The Little Mother," won second prize in that year's St. Louis Artists' Guild contest and was described by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on December 15, 1905 as "a charming study of children, besides possessing technical merit of a high order" (12). Around 1917, Maury designed a poster encouraging food conservation in the United States, featuring a child seated on a chair “licking her plate vigorously” and bearing the slogan, “Lick Your Plate or Be Licked.” Though the poster was criticized in St. Louis as “puerile, wanting in punch and frivolous,” it was nonetheless approved by then-head of the Food and Drug Administration, future president Herbert Hoover (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 9, 1917, 6B).

Maury was an active member of the St. Louis Artists' Guild and also of the Society of Western Artists. Two of her works are owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Sources

- “Bebel’s Warning.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 15, 1905, p. 12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- CFM. "Another View of Negro Equality." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 30, 1901, p. 4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- City Art Museum Saint Louis. Special Exhibition Catalogue: An Exhibition of Pastel Drawings by Miss Cornelia F. Maury, Opening April 16, 1916. Series 1916, no. 10.

- Chopin, Kate. “Letter to Cornelia F. Maury, December 3, 1895.” Kate Chopin’s Private Papers. Ed. Emily Toth and Per Seyersted. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998, p. 208.

- Falk, Peter H. “Maury, Cornelia Field.” Who Was Who in American Art, 1564-1975: 400 Years of Artists in America, volume 2. Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1999, p. 2223.

- Henderson, E.E. “French View of Whistler.” Brush and Pencil, vol. 16, no. 2, August 1905, pp. 88-92. Google Books.

- “Hoover Approves Food Poster Here that Brought Criticism.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 9, 1917, p. 6B. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Old St. Louis Houses: The Guion Home.” St. Louis Star-Times, May 12, 1943, p. 11. Newspapers.com.

- Tillinger, Elaine Celeste. “The lure of the line: Influences, tradition, and innovation in the education and career of a woman artist: Cornelia Field Maury (1866-1942).” PhD dissertation, Saint Louis University, 1995. ProQuest.

- Waters, Clara Erskine Clements. “Cornelia F. Maury.” Women in the Fine Arts: From the Seventh Century B.C. to the Twentieth Century A.D. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1904. pp. 231-2.

- “Woman Fights City’s Attempt to Ruin Landmark. Artist Would Preserve Century-Old House.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 6, 1913, p. A1B. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Women Artists and Their Work. Clever St. Louis Girls Who Can Handle the Brush.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 17, 1895, p. 20. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.