Studio for Portrait Masks, 1918 – 1920

In the aftermath of WWI, it would take years to rebuild France’s infrastructure, economy, social fabric, and people. Among its numerous reconstruction initiatives, the ARC supported and partially financed a project to outfit wounded soldiers with facial prosthetics – they were victims of machine-gunfire, bombs, and grenade explosions. An estimated three million men were wounded between 1914 and 1918, of whom 15,000 – 20,000 suffered facial injuries that forever altered the course of their lives. Marie-Andrée Roze-Pellat remarked in a 2014 article that the memory of World War I "[...] persists in time because, in no other war, did the fighting inflict such damage to the bodies of the soldiers. The injured of the face long remained forgotten in this history.

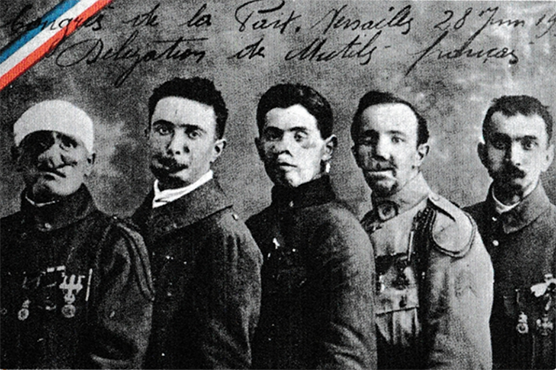

These disfigured soldiers were dismissively assigned the title of “les gueules cassées” (the shattered mugs). Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau somberly evoked their grim reality during the signing ceremony of the Treaty of Versailles: “You were in a bad place…It shows” (Roze-Pellat 2014, 41, translated from the French). After enduring the hardships of warfare, these survivors had returned from the front only to become victims of social stigma, oftentimes even within their own families. Many were abandoned, living as recluses, only venturing out under the cover of darkness. Although some more “fortunate” veterans benefited from the nascent facial reconstruction techniques of the time, all were irrevocably marked, and in need of something to ease their transitions back into society. Prosthetics enabled this to some degree:

It is [...] in this context of the Great War that maxillofacial surgery was structured as an independent discipline. In Paris, the pioneering department of Dr. Hippolyte Morestin established at the Val-de-Grâce welcomed the 5th division of the facial wounded. However, this medical effort to reconstruct faces left deep scars and permanent damage, and remained insufficient to allow soldiers to return to their social lives. The creation of prostheses was therefore essential and the task was entrusted to dental technicians, but also, to a lesser extent, to sculptors (Raingeval 2015, 29, translated from the French).

A group of patients of Mrs. Anna Coleman Ladd, at her studio in Paris on Christmas Day. 1918. Photograph. Library of Congress.

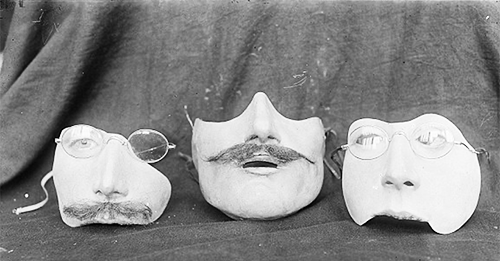

Masks by Anna Coleman Ladd. 1917-1919. Photograph. Library of Congress.

Mrs. Anna Coleman Ladd seated in the foreground surrounded by her patients at her studio, Christmas Day. 1918. Photograph. Library of Congress.

When the American Red Cross moved its headquarters to 4 rue de Chevreuse, apartments in the immediate vicinity were rented to accommodate nurses, orderlies, and other staff. One of those rentals was Janet Scudder's studio at 70 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Run under the auspices of the American Red Cross's "Bureau de Reconstruction et de Rééducation des Mutilés de Guerre," this studio became the setting of a very special project pioneered by American sculptor Anna Ladd, a precursor to what is now known as anaplastology. Beginning in January 1918, 70 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, renamed the Studio for Portrait Masks, welcomed countless French and American soldiers who had been disfigured in combat. Ladd employed her talents as a painter and sculptor to fashion face masks that would provide these traumatized soldiers with internal and external healing, including the restoration of their self-esteem, which had been ripped from them amid the carnage of the war.

Others affiliated with the studio were:

- Jane Poupelet, a French sculptor and draftswoman who also volunteered with the American Red Cross. She co-founded the studio with Ladd and was instrumental in securing Janet Scudder's space for use by the Red Cross.

- Diana Blair, curator of specimens at the Harvard Medical Laboratory.

- Marie Louise Brent, French-American sculptor, who had served with the American Fund for French Wounded in Lorraine.

- Robert Wlérick, French sculptor and friend of Jane Poupelet, who had worked in a facial surgical unit in Bordeaux.

Anna Ladd

Born on July 15, 1878 near Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania to John and Mary Watts, Anna Ladd was a self-styled sculptor who shied away from formal training in art schools. Instead, she drew and modeled from life. She lived in Paris and Rome for 25 years, working throughout her career in studios and receiving criticism from such sculptors as Ettore Ferrari and Emilio Gallori in Rome, Auguste Rodin in Paris, Charles Grafly in Philadelphia, and Bela Lyon Pratt in Boston.

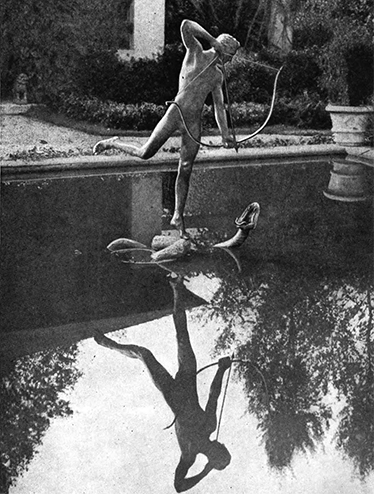

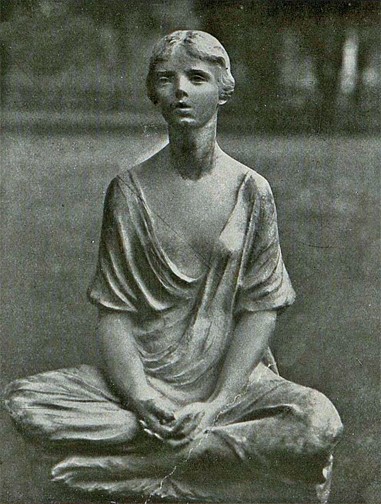

Anna Ladd, "The Idol," representing Mrs. Morgan Belmot, undated, bronze. Reproduced in “An Awakening in Decorative Sculpture,” Harper's Bazaar, vol. 52, no. 4, April 1917, p. 60.

On June 26, 1905, she married Dr. Maynard Ladd, specialist in the diseases of children, in England's Salisbury Cathedral. They moved to Boston, where Maynard joined the Harvard Medical School faculty and Anna continued sculpting while raising their two daughters. One of the daughters would go on to graduate from Vassar College in 1930. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Ladd produced joyful bronze fountain figures for private gardens (e.g. "Sun God" and "Leaping Sprites"), executed several portraits, and also wrote two lengthy novels published in 1912 and 1913 respectively. She once said of her sculptures, "My dream is to work for all outdoors, to produce sculpture to be placed on street corners, on walls, on the open roads" (Seaton-Smith 251).

Between 1907 and 1915, Ladd had solo exhibitions at the Gorham Gallery in New York (1913, 40 bronzes), the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C., and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Her works were also exhibited in Rome (1914), at the Salon des Beaux-Arts (1913), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, and the National Sculpture Society (Boston Daily Globe, November 2, 1915, 12). Several of her bronzes were also shown at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, for which she earned an Honorable Mention.

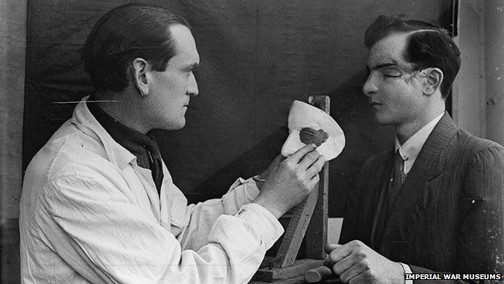

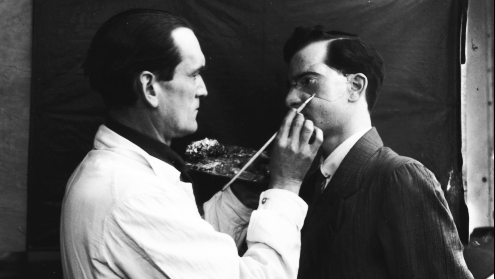

Ladd apparently became acquainted with facial reconstruction through British art critic C. Lewis Hund (Kedey 3). He introduced her to the work of Francis Derwent Wood, a sculptor who had " [...] become the expert on sculpting prosthetic faces. He was a pioneer in the field of developing tin masks by taking casts of the wounded man’s face and smoothing over the areas that had been damaged beyond surgical repair" (Prichard 38). In 1917, she visited Wood in the "Tin Noses Department," which he had established in 1915 at the Third London General Hospital (Kedey 3). Wood encouraged her to do the same kind of work for wounded men in France.

Ladd moved to Paris after her husband was appointed Deputy Commissioner of the Children's Bureau of the American Red Cross (A.R.C.) in Toulouse and served as its medical adviser in the dangerous French advance zones. Inspired by Wood's pioneering work, Ladd decided to join the war effort and put her artistic skills to practical use. She volunteered with the A.R.C. and convinced the War Department to let her establish a studio for disfigured soldiers in Paris, financing it primarily with her own money. Ladd’s work with disfigured soldiers was quickly recognized as important so she obtained authorization from the French Service de la Santé to make these kinds of masks for victims in all ten regions of France. As her reputation grew, she received recommendations from hospitals in Paris (Val de Grace, Chaptal), Rennes, Vichy, Bordeaux, and Neuilly. Soldiers were also referred to her by officials of the A.R.C., which provided additional financial support:

Anna Ladd established work with the centre maxillaux-faciaux of Rennes, Le Mans, Bordeaux and Vichy, and at the Hospital Chaptal in Paris. The American Hospital of Neuilly provided five beds for her work and the Studio received applications from the American Base Hospital No 1. Anna Ladd also visited the hospitals in the Military Zone of Eastern France where her husband, Boston paediatrician Maynard Ladd, established a chain of relief stations for women and children in the Nancy area (Mitchell 53, note 31).

The men who came to Ladd’s studio had already undergone facial surgery and she would determine whether or not she could produce masks for them based on the severity of their injuries:

Our work begins when the surgeon has finished. We do not profess to heal. After the wounded man has been discharged from the hospital we begin our treatment. Of course, the chief difficulty in making these masks is to accurately match both sides of the face and restore the features so that there will be nothing of the grotesque in the appearance of the covering. A mask that did not look like the individual as he was known to his relatives would be almost as bad as the disfigurement (Kedey 3).

The mask process required several sittings, first to make a plaster cast of the soldier’s wounded face, followed by a second cast, and then the fitting and painting:

We [...] create, from a photograph of the disfigured person prior to the injury, a second cast, which is the reconstruction of his normal face. To give his face a semblance of what it was, a perfect logic, and its real psychological expression, a medical examination is often necessary: examination of the throat, the structure of the larynx, etc. All this depends, of course, on the nature of the mutilation and the kind of disaster we have to repair. It's on this second cast […] that is modeled the galvanized-mask, which will ultimately be painted directly on the injured man, with an exact rendition of his skin tone. This work requires a series of rather long and rather delicate processes; when it is over, and the adaptation is what it should be, that is to say, narrow, impeccable as far as the case allows, it is difficult to realize that the one who wears this mask thus connected to his features, is, most of the time, completely disfigured (translated from French, Wlérick as cited in Junka 11).

In order to obtain a real likeness in the reconstruction, Ladd would request pre-injury photos from each soldier. A silversmith named Christofle would create a galvanized copper prosthesis, which was painted to match the soldier's skin tone with washable enamel paint. Eyes and a mustache or beard made of metallic foil were sometimes added to the mask, which would be attached to the face either with glasses or an almost invisible strip hooked behind the ears or even a small amount of spirit gum. The mask could be removed when the person needed to eat or sleep, and the lips were always left slightly open so the person could speak or smoke (cf. Mainz). Ladd would often suggest recipes for drinks, soups, and creams that were well-suited for those wearing portrait masks (Cookery Receipts).

A masking was considered successful when the patient could walk down a Parisian boulevard without being noticed. Earlier, after their multiple surgeries were complete but before they were fitted with masks, the men had gone on supervised forays into the city, accompanied by their nurses, only to find that onlookers gawked at them and sometimes even fainted. The men called this the Medusa effect. The masks allowed them to regain some measure of the social visibility they had forfeited because of their ghastly wounds (Lubin 2008, 11).

According to the American Magazine of Art, only a talented artist could have executed such a complex undertaking as these masks:

These masks are of the thinnest, lightest metal and are produced by a system of electrolysis from casts. They are, moreover, painted with a celluloid paint, in exact imitation of the flesh. The lips are always modeled slightly open so that the wearer can smoke and speak. Of her subjects Mrs. Ladd made careful study. Where photographs were obtainable she followed them, but where they were not she gave expression to the features which seemed in harmony with the character of the man. None but an artist who had given much time to portraiture and was peculiarly gifted along these lines could have accomplished such satisfactory results (June 1919, 309).

Initially, the effectiveness of the masks was highly contested (Feo 25), especially since many soldiers received only one mask apiece: masks had a limited shelf-life, caused irritations, and other inconveniences (Delaporte 121-122):

The reality is not so miraculous. First of all, from a practical point of view, the masks and prostheses all had drawbacks, whether they were made of gelatin, plastic, vulcanite or painted metal. They could very quickly lose their original color, inducing a humiliating difference between the complexion of the mask and that of the face. They often had to be restored or even replaced. Finally, wearing items made of copper or containing glue could cause severe skin irritation, not to mention the inconvenience due to their weight. This is why the enthusiasm generated by the prostheses could sometimes quickly give way to disappointment and resignation, the cripple resolving to show his face as it is. Historians Sophie Delaporte and Katherine Feo thus consider that the use of facial prostheses has ultimately constituted a relatively marginal solution (Ackerman 17).

But as Ladd and the other Studio artists gained experience, the masks became lighter, and the paint, which was procured in the United States, was permanent rather than washable. According to Wlérick, the masks were unalterable and could last indefinitely if the soldiers took good care of them (cited in Junka 12). Ladd would eventually receive a flood of letters, reports, and poems from French surgeons, disfigured soldiers and their families, praising her efforts. A Red Cross report cited several of these testimonials:

The masks are so thin and light that one man wrote he forgot to take it off at night. Another said that the police no longer demanded to see his papers daily, as they did not suspect them of being a mutilé. (Mixer, December 1919, 1)

“Thanks to you, the despairing rejoice, the damned return to hope, the gentle wives and mothers will again find the faces they wept for….. What Sculptor could do more? And by what precious and new words can one thank you?” (Mixer, December 1919, 13)

These masks are as interesting from the artistic, as from the practical standpoint. They permit mutilated men, awaiting operations or whose wounds are beyond the resources of surgery, to circulate without attracting attention, or without being the object of repulsion to those even who most appreciate their admirable conduct. I offer you my sincere thanks for those especially disinherited ones…. (Mixer, December 1919, 12)

After visiting the Studio, the eminent French surgeon Paul Desfossés lauded Ladd’s endeavors in a French medical journal:

“All her talent, all her heart, Mrs. Ladd concentrates on those mutilated whose horrible wounds have rendered them unrecognizable event to their mothers. I know well that our surgeons, our Morestins (name of a reputed surgeon), are excellent at reconstructing faces on these formless masses of red flesh; but can they give them back their own features, which a mother, a wife, have loved. The results obtained are truly astonishing: a stupendous illusion of reality […] I advise my surgical colleagues to visit her studio” (Report in Hoover_xx482_bx81_fl17, p. 2).

Ladd even received recommendations that the work she had begun in Paris should be continued back in the United States. Homer Folks suggested to Major Perkins in his May 21, 1918 memo that the American Red Cross establish an agency and a plant to make portrait masks for wounded Americans, to be overseen by Harvard Medical School under the supervision of Anna Ladd. In a July 23, 1918 letter to Ladd, Harvey Gibson, Red Cross Commissioner for France, said he would recommend to the Red Cross in Washington that “[…] they should endeavor, if possible, to make some arrangement by which you would become associated with our Bureau of Re-Construction and Re-Education, which would include the work for mutilés, in which work you have been so wonderfully successful here.” He also stated that Harvard should not be involved since the Bureau would have oversight.

Having worked assiduously in Paris for eleven months, Ladd returned to Boston in early December 1918 because she lacked the necessary funding to continue her efforts. Furthermore, the Children's Division of the Red Cross was progressively shutting down activities and her husband could return to his pre-war practice. Anna Ladd left behind lists of the names of soldiers to whom she had delivered masks and those who were still waiting to be outfitted. According to these lists, by November 23, 1918 she had delivered 57 masks and had begun 14 for the 59 new applicants (Hoover_xx482_bx81_fl17). Several of those she had begun must have been completed in 1918 since Col. Knowlton Mixer's August 1919 report for the Department of General Relief stated that a total of 67 masks had been completed in 1918 (13).

Right before her departure, Dr. Léon Dufourmontel from the Rennes Center for maxilla-facial reconstruction, who had collaborated with the Studio, wrote to say he regretted her departure:

Your upcoming departure for America will be regretted by many French people who have appreciated your very active devotion […] Will I have the joy of decorating my living room with a sample of your talent? I will come to Paris next week and would be happy to receive it from your very hands (translated from French).

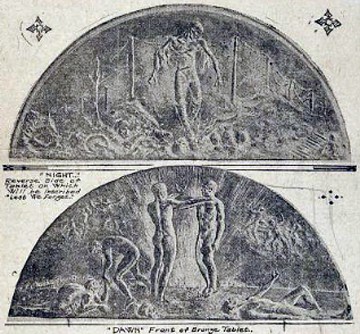

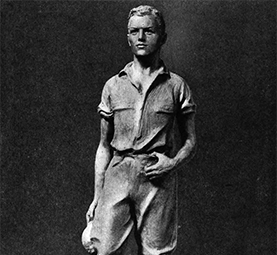

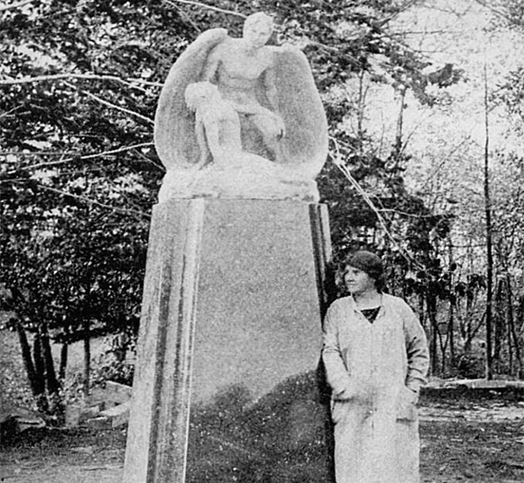

Despite her success with portrait masks and entreaties from Red Cross officials, Ladd chose to return to sculpting and painting, working in Boston and Beverly Farms, Massachusetts, in the studio she called "Arden." She executed portrait busts, reliefs, symbolic figures, and fountains. The magnitude of the suffering she had witnessed in WWI had a significant impact on her sculptural work, which shifted away from her lighthearted pre-war bronzes. She designed memorial tablets and several war memorials: Studebaker Memorial in South Bend, Indiana; the Aldrich Memorial in Grand Rapids, Michigan; and the Russell Memorial in Andover, Massachusetts. Ladd also produced two memorials for the American Legion, one commissioned by the Manchester-by-the-Sea Legion; the other entitled, Cost of Victory, in the American Legion Lot in the Beverley Farms cemetery.

In 1923, Ladd was granted an honorary Master of Arts degree from Tufts University. She characterized the sculptor's challenges during an address at a Plaza dinner for the American Women's Association Club on May 5, 1925:

"Sculptors, to be any good at all, have to touch all sides of life. They deal in material and in spirit. The grace of the figure they model is based on the accurate mechanism of armatures. They must have the physical strength of a blacksmith, the skill of a carpenter, the precision of a dentist, the knowledge of anatomy and psychology of a physician. Not only this but they must have training in archaeology, mythology, history, and architecture, for the relation of the part to the whole is of the most vital importance in sculpture. [...] they must have the soul of a poet and the creative energy of a god [...]" (Archives of American Art, SOVA: laddanna, box 2, folder 66, 1934642).

Interestingly, the noted French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle echoed these sentiments in 1926 at his workshop in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière:

“Bourdelle said to-day—during his criticism at the Chaumière—‘A sculptor must be the composite of many contrary things. He must have the knowledge of a philosopher, the simplicity of a child—the soul of a poet and the science of a mathamatician [sic].’ Something to live up to, n’est pas?” (Gregory 95).

Ladd was made Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1932 in recognition of her contributions to the well-being of French veterans (her New York Times obituary says she was decorated in 1934). She also was a recipient of the Serbian order of St. Sava.

Anna Ladd died of illness on June 2, 1939 at the age of sixty, shortly after she and her husband had moved to Santa Barbara, California. Maynard Ladd died in 1942. Her papers can be accessed at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

Sources

- Ackerman, Ada. "Redonner visage aux gueules cassées. Sculpture et chirurgie plastique pendant et après la Première Guerre mondiale." RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, vol. 41, no. 1, 2016, pp. 5-21. JSTOR.

- Alexander, Caroline. “Faces of War.” Smithsonian Magazine online, February 2007.

- "An American Sculptor's Splendid War Work." The American Magazine of Art, vol. 10, no. 8, June 1919, pp. 309-310. JSTOR.

- “An Awakening in Decorative Sculpture.” Harper's Bazaar, vol. 52, no. 4, April 1917, p. 60. ProQuest.

- An International Adventure: What the American Red Cross is doing for the Civilians of France. American Red Cross, 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives.

- “Anna Coleman Ladd: The Sculptor of Faces.” "La Burbuja Rosa" blog, March 23, 2017.

- “Anna Coleman Ladd, ‘The Idol,’ Representing Mrs. Morgan Belmot.” Harper’s Bazaar, vol. 52, no. 4, April 1917, pg. 60. ProQuest.

- Anonymous. "Untitled Report on the work of remaking the faces of wounded solders." 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx 81 fl 17, pp 1-3.

- Bainbridge, William Seaman. Report on Medical and Surgical Developments of the War. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1919, pp. 85-91. Google Books.

- Biernoff, Suzannah, Portraits of Violence: War and the Aesthetics of Disfigurement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017.

- Biernoff, Suzannah and Jane Tynan. “Making and Remaking of the Civilian Soldier: The World War I Photographs of Horace Nicholls.” Journal of War & Culture Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, December 2012, pp. 277-293.

- Delaporte, Sophie. Gueules cassées, les blessés de la face de la Grande Guerre. Agnès Viénot éditions, 2001, pp. 121-122.

- “Dr. Maynard Ladd, a Pediatrician, 69: Ex-Associate at the Harvard Medical. School Dies.” New York Times, 11 March 1942, p. 19.

- Dufourmontel, Léon. Letter to Anna Ladd, November 30, 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx81 fl16.

- Feo, Katherine. “Invisibility: Memory, Masks and Masculinities in the Great War.” Journal of Design History, vol. 20, no. 1, Spring 2007, pp. 17-27. JSTOR.

- Folks, Homer. Inter-Office Letter to Major Perkins. May 21, 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx82 fl12.

- Gibson, Harvey D. Letter to Mrs. Maynard Ladd. July 23, 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx82 fl12.

- Goran, David. “Anna Coleman Ladd – American Sculptor Who Devoted Her Time Throughout WWI to Soldiers, Who Were Disfigured.” August 21, 2016. The Vintage News.

- Graham, Regina F. “American Socialite and Sculptor…” Daily Mail UK online, August 14, 2018.

- Gregory, Angela and and Nancy L. Penrose. A Dream and a Chisel: Louisiana sculptor Angela Gregory in Paris, 1925-1928. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2019.

- Jalinière, Hugo. “La bataille de Verdun, un tournant dans la médecine de guerre.” Sciences et Avenir, October 10, 2016. Sciences et Avenir.

- Junka, Paul. “Le masque de gloire,” La Renaissance, vol. 7, no. 7, March 29, 1919, pp. 9-12. Gallica.

- Kedey, J. "Masks for the Maimed." San Francisco Chronicle, May 5, 1918, p. 3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Ladd, Anna Coleman. Address delivered at the Plaza. 5 May 1925. Smithsonian Archives of American Art, document no. 1934464.

- Ladd, Anna, “Cookery Receipts for the Mutilés de la Figure.” 1918. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Ladd, Anna Coleman. Hieronymus Rides: Episodes in the Life of a Knight and Jester at the Court of Maximilian, King of the Romans. Macmillan and Company, Ltd., 1912.

- Ladd, A., "How Wounded Soldiers Have Faced the World Again with "Portrait Masks", interview by P. King, St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 26, 1933, clipping in Ladd's archives (cited in Mitchell 53, note 33).

- Ladd, Anna Coleman. The Candid Adventurer. Houghton Mifflin, 1913.

- Ladd, Maynard. “The American Red Cross in the Meurthe-Et-Moselle.” American Journal of Diseases of Children, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 236-241. JAMA Network.

- Leases of Montparnasse studios and apartments, RH archives.

- “List of Portrait Masks Delivered to Date Nov. 23 (1918).” Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx81 fl17.

- “List of Blessés Waiting for Masks November 23, 1918.” Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Lubin, David. Grand Illusion: American Art and the First World War. Oxford University Press, 2016. His footnote 34 identifies documentary sources for Ladd's work.

- Lubin, David. "Masks, Mutilation, and Modernity: Anna Coleman Ladd and the First World War." Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 47, no. 3-4, Fall 2008, pp. 4-15.

- Mainz, Valérie and Griselda Pollock. Work and the Image: v. 2: Work in Modern Times - Visual Mediations and Social Processes, Routledge, 2018.

- Marshall, Clive. “Mending the Men and the Cities of France.” San Francisco Chronicle. December 8, 1918, p. SM5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- McFadden, Terri. “Sculpture in War and Peace.” Historic Beverly: Chronicles of a Coastal town, 2018, pp. 142-145. Google Books.

- “Miss Ladd Engaged to Gregory Vlastos: Boston Girl's Betrothal is Announced by Her Parents, Mr. and Mrs. Maynard Ladd.” New York Times, 11 September 1932, p. 29.

- Mixer, Knowlton. “Bureau of Portrait Masks.” Report for the Department of General Relief, August 1919, pp. 12-13. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx76 fl23.

- "Mrs. Anna C. Ladd, Sculptor, is Dead: Rebuilder of Soldiers' Faces." New York Times, 4 June 1939, p. 48.

- “Mrs. Ladd, Sculptress, III. New York Times, August 12, 1934, p. 25.

- Muir, Ward. “Masks and Faces,” The Happy Hospital, London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd.,1918, pp. 143-155. HathiTrust. *Anna Ladd kept this work in her portrait studio.

- Muir, Ward. “The Men with the New Faces.” The Nineteenth Century, October 1917, p. 752, article in Ladd's papers. Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- "New England Women." Boston Daily Globe, Nov 2, 1915, p. 12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Parker, Harold M. “Masking the War Maimed.” Illustrated World, vol. 29, no. 3, 1918, pp. 349-352. Medical Services and Warfare (Adam Matthews database).

- Powell, Julie M. “About-Face: Gender, Disfigurement and the Politics of French Reconstruction, 1918–24” Gender & History, vol. 28, no. 3, November 2016, pp. 604-622.

- Prichard, Brenna K. "Boys on Blue Benches: Disfigured Veterans of the First World War." Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, MA thesis, 2016.

- Red Cross Work on Mutilés at Paris, 1918. Video. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

- Report on the work of remaking the faces of wounded soldier, untitled and undated, with quotes from soldiers, doctors, and politicians, p. 1-3. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Roze-Pellat, Marie-Andrée. "La réparation des gueules cassée." Corps, vol. 1, no. 12, CNRS éditions, 2014, pp. 41-48.

- Scudder, Janet. Letter to Anna Ladd. May 7, 1919. Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art 1932 728. Image 6.

- Seaton-Schmidt, Anna. “Anna Coleman Ladd: Sculptor.” Art and Progress, vol. 2, no. 9, July 1911, pp. 251-255. JSTOR.

- “She Will Repair Wounded Faces.” The Washington Post. November 11, 1917, p. ES3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Shelton, Don. “Ladd, Anna Coleman Watts – Self Portrait.” 20C – American Miniature Portraits.

- “Skeleton Caught in Barbed Wire.” The World, December 2, 1928. Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- Smithsonian On-line Virtual Archives (SOVA): A Finding Aid to the Anna Coleman Ladd Papers, 1881-1950, Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- “Some Recent Work by Anna Coleman Ladd.” Harper's Bazaar, vol. 58, no. 2556, October 1925, p. 132. ProQuest.

- “The Artistic Temperament.” New York Times. May 11, 1913, p. 21. Review of Ladd’s book, The Candid Adventurer.

- The Work of Anna Coleman Ladd. Seaver-Howland Press, 1920. Library of the Fogg Museum of Art, Harvard University.

- Tutwiler, Julia R. “Women Who Achieve Anna Coleman Ladd." Harper's Bazaar, vol. 50, no. 3, March 1915, p. 39. ProQuest.

- “Two Fountains by Anna Coleman Ladd,” Art and Progress, vol. 3, no. 12, October 1912, pp. 740-742. JSTOR.

- “Two of the Foremost American Sculptors.” Harper's Bazaar, vol. 52, no. 10, October 1917, p. 56. ProQuest.

- Vaillant, Franz. “11 novembre: ces femmes qui réparaient les ‘gueules cassées’," Terriennes, TV5 Monde, 2019.

- “Works by Anna Coleman Ladd.” The American Magazine of Art, vol. 9, no. 10, August 1918, pp. 406-407, 431. JSTOR.

NOTE: "Ladd kept a copy of [... ] Wood’s Lancet article and Muir’s The Happy Hospital among her possessions in the studio" (Prichard 44).

Marie-Louise Brent

Marie-Louise Brent joined the Studio for Portrait Masks in September 1918, around the same time as Wlérick and Blair. She had served as the secretary to the American Fund for French Wounded in Lorraine and then became the Studio's secretary (Mitchell 40), overseeing day-to-day administrative questions, correspondence, and finances. Since Anna Ladd was often absent, working in the field or with heads of different surgical units in France, managing the studio was an important responsibility especially since visitors often came to see the place and soldiers gathered there socially. Brent also was an artist of some repute but it is unclear if, under Ladd’s watch, she also contributed to modeling and painting masks.

According to her reports to the Red Cross, Anna Ladd left France in December 1918, having completed 57 masks and begun another 14, 10 of which were completed by the end of the year. All told, 67 masks were delivered in 1918 (Mixer, August 1919 Report, 13). It must be noted that secondary sources often provide erroneous statistics on the number of masks that were generated by Ladd and by the Studio in general. The numbers provided here stem from Red Cross reports.

The Studio continued its work under the direction of Marie-Louise Brent, seconded by sculptors Jane Poupelet and Robert Wlérick. From January 1 to September 1, 1919, they delivered 93 masks. Circumstances, however, were less than satisfactory, mainly because the space used to create the portrait masks belonged to Janet Scudder, who did not see eye to eye with Brent. In February 1919, Scudder suggested that her space was not fit for the Studio, and proposed a move or several upgrades. Neither proposal met with an enthusiastic response from Brent (Feb. 12), who immediately turned to the Red Cross for help, asking if space could be secured at 4 rue de Chevreuse when the Military vacated the property (Brent to Hoyt, February, 19, 1919). Red Cross officials, however, firmly stated that the rental of Scudder’s studio was valid until one month after the signing of the peace treaty (Hoyt to Brent, February 19, and 25, 1919).

While Scudder seemed to support the mask initiative, she repeatedly asked when the Studio would vacate her space. In April, she wrote to Brent once again, asking her when she was moving, claiming that Poupelet had told her that an arrangement had been made for the Studio to be integrated into the facility at 4 rue de Chevreuse (April 15), which Brent denied. Failing to convince Brent to leave, Scudder wrote to her saying that she did not want to undermine the project that Ladd had so masterfully carried forward. She proposed that the Studio remain in her space, promising to upgrade the facilities, but only if Poupelet was put in charge (April 27, 1919). Brent sharply replied that she took her orders from the Red Cross on matters concerning the Studio and that they would move as soon as a new location was secured in the neighborhood (May 3, 1919).

Scudder clearly had underlying issues with how the Studio was being managed, which were distinctly outlined in her letter to Ladd on May 7, 1919. She painted the picture (perhaps exaggerated) of a rather disastrous operation:

"It is one grand pity that you left Paris and I wish that you could come back. Your great work for the French mutilées [sic.] is in the hands of a little person who has the soul of a flea. I suppose Mlle Poupelet has written you frequently and that you know how the work you started in Paris has grown and how more and more mutilées apply for missing features. Often there have been as many as 18 people in the studio at one time, there is not room to turn about in it. Since your departure the place is closed every day until around 2 o’clock and the mutilées are not allowed to enter until that hour. One poor thing came all the way from the provinces to get fixed up. He had just enough money to get here and back, arrived on Saturday afternoon, place was closed until Monday at 2, he did not have money enough to stay, so he went home" (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution).

In the same letter, Scudder said she had submitted a long report detailing her concerns to Red Cross officials. When Brent received the report, she claimed it "[…] was a deliberate exaggeration, written for the purpose of regaining possession of the studio!" (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution). Ultimately, Scudder won her case and reclaimed 70bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs on May 14, 1919. Brent and the Red Cross had managed to secure one of the studios rented by Elisabeth Mills Reid on the ground floor of 86 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. It appears that only Brent moved to the new space, since her letter to Scudder informing her that she had vacated the studio, also mentioned that Poupelet and Wlérick would receive their personal property at their respective addresses (May 14, 1919).

It is difficult to determine with whom Brent worked when the Studio moved up the street, or if she hired the clay modeler N.R. Cheesebrow, recommended by Captain Miller of the Red Cross (Letter to Brent, May 15, 1919). Yet work continued apace and, in August 1919, the new studio was renamed the Bureau of Portrait Masks and placed under the Red Cross Department of General Relief, headed by Knowlton Mixer whose office was at 4 rue de Chevreuse. In his September 1919 report, Mixer stated that 175 masks had been delivered from January to September 1 and that 162 soldiers had visited the Studio. He further announced that the Red Cross would subsidize the project until the end of 1919 (August 5, 1919).

For reasons unknown, it was impossible for the Studio to remain at 86 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Mixer received permission to install it at the Hospital of the Val de Grace, Service de la Santé. Brent resigned around November 1 and was replaced by Emma Leven as head of the Studio (Report, December 4, 1919). Work continued under the auspices of the Red Cross until January 1,1920. Mixer reported that the Studio delivered 28 masks in November and 17 more in December for a total of 220 for the year (December report, p. 14).

Receipts show that supplies seem to have been bought by the ARC through February 1920 (Hoover xx482 bx 81 fl18). All the while, Mixer explored ways for the project to be transferred to French control. He reported that 12,000Fr had already been secured in November through the Oeuvre des Blessés au Travail (Report, November 1919, p. 15) and announced that by February 1920, the Service de la Santé would contribute another 12,000Fr to pay for the Directrice, two sculptors, and an assistant (Report, December 1919, p. 14). According to Mitchell, the two artists were Wlérick and Poupelet, who "insured the continuity of the practice, he until September 1919, she until winter 1920 when she offered to pass on the technique to another person" (41). In his January 2020 report, Mixer stated that the Studio had been taken over by the French Service de la Santé by February 1, 2020, and that the ARC contributed 2,000FF to cover maintenance expenses in January (Hoover XX482 bx82 fl 21)

Aside from the crucial work of producing portrait masks, the Studio continued to be a social hub, with soldiers coming to the studio not only to have their masks repaired but also to enjoy each other’s company. A Christmas party in 1919 included gifts, refreshments, and speeches, and was attended by 140 soldiers (Mixer December 1919 report, p. 14).

According to a post on La Marelle (no longer accessible) https://www.la-marelle.org/des-masques/:

"One of the discoveries we made in the abandoned cellars of the Hôtel Saint-Marc, adjoining the Saint-André hospital, were several trunks containing plaster casts of jagged faces, as well as final masks painted with hair, mustaches, and dyed fresh."

Brent sent 50 and promised a total of 300 plaster casts to the Red Cross Museum in Washington (letter to Hunter). She listed the names of each soldier, the wounds from which they suffered, and the hospital and surgeon who had referred them to the Studio. According to correspondence with the Red Cross, it seems that the casts, together with photos, were to be exhibited. Some were placed on loan with the Army Medical Museum since the Red Cross Museum did not have enough room to house them (Givenwilson). We have found no information to date on whether the casts were actually exhibited.

Sources

- Brent. Letter to Janet Scudder. 17 February 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Brent. Letter to Elizabeth S. Hoyt. 19 February 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Brent. Letter to Janet Scudder. 16 April 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Brent. Letter to Janet Scudder. 3 May 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Brent. Letter to Janet Scudder. 14 May 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Brent. Memorandum to Major Knowlton Mixer. 8 August 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Brent. Letter to Lewis J. Hunter. 1 September 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Brent. Letter to Colonel J. Manley. 7 October 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Campbell, F. Letter to Brent. 4 September 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Givenwilson, I.M. Letter to Brent. 23 September 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Hoyt, Elizabeth S. Letter to Brent. 19 February 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Hoyt, Elizabeth S. Letter to Brent. 25 February 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Hoyt, Elizabeth S. Letter to Brent. 26 April 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Hoyt, Elizabeth S. Letter to Brent 29 April 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx 482 bx81 fl18.

- “List of Plaster Casts Sent to Washington.” 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. HooverXX482, bx. 81 fl17.

- Miller, H. W. Letter to Brent. 15 May 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Letter to Brent. 5 August 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report to Colonel Robert E. Olds (sent 9 October 1919) for the Department of General Relief, August 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx76 fl23.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report to Major C.R. Corbin: "List of Activities Remaining under the French Commission." 10 September 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx82 fl17.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report September 1919, Commission for France. p. 13. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Letter to Brent. 7 Oct. 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report November 1919, Commission for France, p. 15. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx82 fl19.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report December 1919, Commission for France, p. 14. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx82 fl19.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Memo to Col. Robert E. Olds, Commissioner for Europe, on the Departments under the French Commission. 4 December 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx82 fl17.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Order for Supplies to Major Payson. December 11, 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Order for Christmas Celebration for Mutilés at Studio for Portrait Masks. Val de Grace. 13 December 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Cable to American Red Cross in Washington D.C. 15 December 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl18.

- Mixer, Knowlton. Report January 1920, Commission for France, p. 12. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx82 fl21.

- Scudder, Janet. Letter to Brent. 12 February 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Scudder, Janet. Letter to Brent. 15 April 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx482 bx81 fl17.

- Scudder, Janet. Letter to Brent. 27 April 1919. Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Hoover xx 482 bx81 fl18.

- Scudder, Janet. Letter to Anna Ladd. 7 May 1919. Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art 1932 728. Image 6

Jane Poupelet

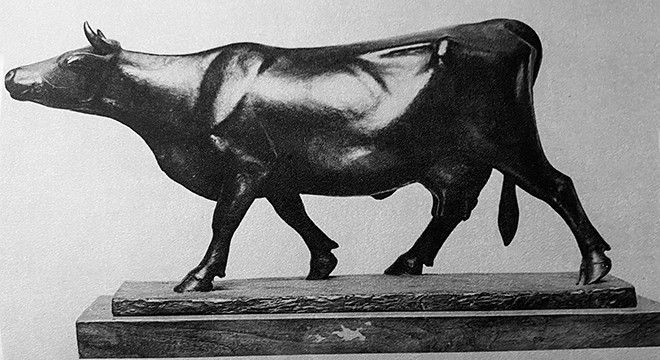

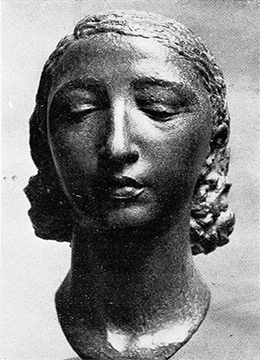

Jane Poupelet, "Femme à sa toilette," n.d., bronze. From.

Jane Poupelet, "Femme se mirant dans l'eau." From Martinie, p. 87.

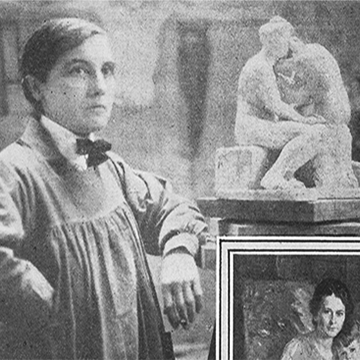

Marie Marcelle Jane Poupelet, whose work was largely forgotten in the aftermath of WWII, was critically acclaimed in her day, gaining success among critics and press. Today, she is recognized as one of France’s foremost sculptors; she gained notoriety in the United States where her works can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Femme à sa toilette,” and several drawings), the Brooklyn Museum of Art (“Femme assise,” several drawings), the Chicago Art Institute (several drawings). A retrospective exhibition was held in several French museums between 2005 and 2006 (La Piscine, Roubaix; Musée des beaux-arts, Bordeaux; Musée Despiau-Wlérich, Mont-de-Marsan), with a comprehensive catalogue of her works, including several articles about her life and work (Rivière).

At a time when women sculptors faced untold barriers and prejudice, Poupelet diligently pursued her calling, initially submitting her work, as many women artists did, under a man’s name. Indeed, women sculptors we not necessarily welcome in a male-dominated artworld:

The fact that a woman can knead clay and wield hammer and chisel with vigor is surprising and disconcerting at first. Sculpture is not the work of a lady. There are many ladies who do their best, however. But their work, which has grace, sometimes, is still lacking in robustness, grandeur, and style. So much so that we are astonished that, by defying all anti-feminist prejudices, the art of Miss Jane Poupelet has precisely these qualities of style, grandeur, and robustness until now considered to be an exclusively male prerogative (translated from the French, Pays 4).

Born on April 18, 1874, daughter of a lawyer and government official, Poupelet grew up in the in the small village of St-Paul-Lizonnes in the Périgord. Although her parents initially did not approve of her artistic endeavors, they later provided her with full moral and financial support (Le Temps 1935, 5).

She began working with clay at a very young age, modeling farm animals and caricatures of her entourage (Myra 1). After spending several years in a boarding school, she was the first woman admitted to the École des Beaux Arts de Bordeaux (1892). There, she studied under a certain Mr. Braquehaye and passed the exams toward the diploma of drawing professor in May 1892 (Diplôme 3); she also attended anatomy and dissection classes at the Faculté de médecine de Bordeaux (Rivière 142). Since her parents, who initially did not approve of her career choice, had cut off her funds, she taught drawing classes and sold her own works, gathering enough money to go to Paris in late 1896 (T.S. 4). She attended the Académie Julian for a month and a half in Denys Puech’s atelier (Martinie 88), but was dissatisfied and went back to Bordeaux. According to Rivière, she returned to Paris from time to time but only settled there around 1900. In Bordeaux, she briefly met French feminist Hubertine Auclert and would later move in Anglo-Saxon feminist circles when she made Paris her home.

Around 1900, Poupelet entered the Paris atelier of Lucien and Gaston Schnegg, whom she had met earlier and for whom she had great admiration, working with them for three years (Martinie 88). She also posed for Lucien who executed a plaster cast of her portrait-bust (completed in 1901), now at the Musée d’Orsay. The cast led to several renditions: one in marble (shown at the 1903 Salon and then exhibited at the Luxembourg museum by 1904); others in lost-wax bronze with black or gold patina (See Musée des Beaux-arts de Bordeaux).

Poupelet began her career under the male pseudonym Simon de Lavergne, which, according to Rivière (18) was the last name of cousins of her mother. Between 1898 and 1901, she submitted work to the Salon of the Société Nationale under this pseudonym (Lepoittevin; Myra 1). Unbeknownst to members of the jury of the 1900 Salon, it was actually Poupelet who was awarded the silver medal for a “decorative vasque” (Myra 1).

Lucien Schnegg was impressed by her talent and told her she had no need for an instructor (Guillemot 52). Boosted by his support, she began showing in her own name. In 1904, she joined the atelier in an exhibition at the Galerie Barbazanges. When Lucien died in 1909, she stayed in close contact with his brother Gaston, remaining part of the group of young independent sculptors dubbed by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles as the “bande à Schnegg.” While they did not constitute a real movement, the group worked in or gravitated around the atelier and included such artists as Charles Despiau, Alfred Jean Halou, Léon Drivier, Henry Arnold, Louis Desjean, François Pompon, Albert Marque, Yvonne Serruys, and Robert Wlérick.

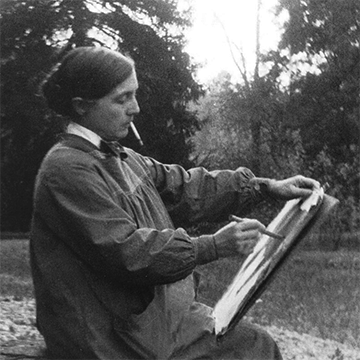

Photo of Jane Poupelet in her studio. From Paris Times, p. 2.

Photo of Jane Poupelet drawing outdoors. From Rivière, p. 38.

In November 1902, Poupelet moved to the place that would become her home and atelier at 30 rue Dutot near the Institut Pasteur, in the same street as the Schneggs (40 rue Dutot) and Wlérick (36 rue Dutot) (Rivière 143). The area was still quite rural and her place abounded in her favorite animals – cats, rabbits, chicken, and ducks (Briot 84, note 322):

In the suburbs [the 15th arrondissement!], she owned a small, curious house where the most diverse animals lived in good intelligence. She loved animals. In her admirable works, she entrusted them with a particularly moving and prestigious nobility. Her bronzes, her drawings, were inspired by an ardent understanding, an exquisite grace, a deep truth (Annales africaines 11).

During the summer months, she stayed at her farm/studio, near her family home (Kunstler, 1932), the Château la Gauterie, which had been built for her grandfather in 1860 (now a hotel and wedding venue). Having reconciled with her parents, she benefited from their support and thus enjoyed some financial independence (À propos 5). According to Briot, she lived alone and had no children, “her artistic career and feminist commitment made partly possible by renouncing on marital life” (56). From 1904-1909, she also had an atelier at 14 ave du Maine, near Fernand Léger and André Mare (Rivière 143).

Jane Poupelet, "Baigneuse," n.d., bronze. From Dussourt, p. 12.

Jane Poupelet, "Devant la vague," n.d., plaster. From Kahn, p. 80.

Jane Poupelet, "Anon," n.d., bronze. From Kuntzler, 1930, no. 5.

In 1904, Poupelet also showed four of her sculptures at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-arts, including her much-criticized “Enterrement à la campagne” (Martinie 88). She was awarded a travel grant by the Société Nationale, and toured Italy, Sicily, Tunisia, Algeria, and Spain between 1904 and 1905 (Pays 4, Martinie 91), accompanied by painter Charlotte Chauchet (Rivière 143). Her contact with Greek and Egyptian sculptures seems to have had a strong impact on her future work.

She continued exhibiting in various Paris salons and galleries until 1912 (see Rivière’s list of exhibitions (148-155).

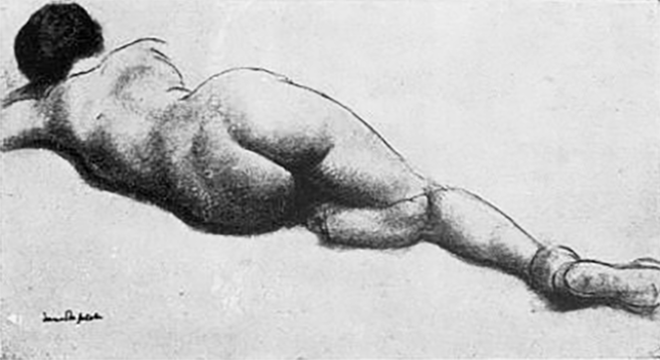

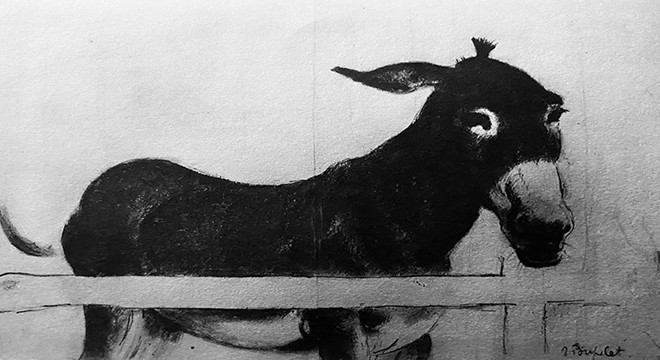

Her sculptures and drawings fall into two main categories: female nudes and domestic or farm animals, always in an attitude of movement or repose. Drawings were an important part of her sculptural work: she began drawing from life the different poses taken by animals or women, initially producing single copies of figures that she plunged in bronze but chased and patinated herself (Lepoittevin). She is known for her relentless and meticulous work, always insisting on the faultless quality of the final product (Martinie 96):

Always dissatisfied, when she sculpts, she imposes a whole series of tasks on herself. Once her sketch is completed and molded, she compares the plaster figure to her model, constantly correcting it by observing it. She then looks for the fitting and the subtle passages of the modeling, and places the details accordingly. She also focusses on the plays of light because she wants her statue to seem like she made it all at once, to form one block (translated from the French, Kunstler, 1930, 9-10).

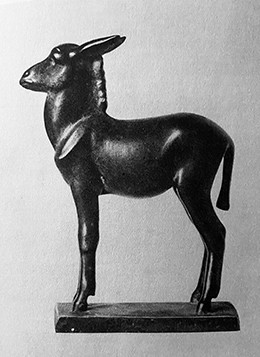

Anne Poupelet, "Vache Marchant," n.d., bronze. From Kunstler, 1930, n°4.

Jane Poupelet, "Femme couchée," n.d., drawing. From Ladoué 43.

Poupelet came into contact with Rodin and was close to Bourdelle. She also socialized with numerous women artists who came to Paris at the turn of the century, among them sculptors Malvina Hoffman and Janet Scudder, and painter Elizabeth Nourse. Scudder, who like the others was associated with the American Girls’ Art Club at 4 rue de Chevreuse, met Poupelet by happenstance around 1911 and came to play a rather important role in her life:

While living in the Rue de la Grande Chaumiere, I made one of my best friends among the French people - a friendship which has increased with the years and which has had something to do with the appreciation of modern French sculpture in America. Our meeting came about in a rather entertaining way. I happened to look in at an exhibition one day and came across a little bronze, a really superb piece of work representing nothing more important than a rabbit – but something that appealed to me at once as being a very beautiful work of art. I bought that rabbit on the spot – the only piece of sculpture I have ever bought – and gave my address for its delivery at the close of the exhibition. A few days later my servant brought a card up to the studio - the card of Mademoiselle Jane Poupelet, sculptor of my precious rabbit. She explained that she had called to have a look at an artist who had bought the work of another woman artist […] Returning her visit almost immediately, I found, in her studio in the Rue Dutot, a collection of small bronzes that convinced me that Mademoiselle Poupelet was one of the most important sculptors of our times (237-238).

Scudder was actually responsible for introducing Poupelet to the United States. She brought seven of her sculptures with her back to New York in 1913, where the female figurines and small animals enjoyed immediate success after The Metropolitan Museum of Art bought her “Femme à sa toilette.” News articles about Poupelet’s work proliferated, and Scudder even wrote an article in Harper’s Weekly in praise of her friend’s work. Poupelet’s “Femme à sa toilette” was represented at the Armory Show (February-March 1913), together with Maillol, Lehmbruck, Brancusi, and others (Briot 112).

Jane Pouplet working on one of her dolls. Gramho.com, instagram post

Jane Poupelet in the Studio for Portrait Masks, ca 1919. Rue 89, Bordeaux, p.?

Photo of Jane Poupelet and soldier in Studio for Portrait Masks. Library of Congress.

With the onset of WWI, Poupelet created several series of wooden toys and rag dolls, holding exhibition sales at the Union Centrale des Arts décoratifs, 1916, the Pavillon de Marsan, 1917, and the Galerie Devambez, 1918. The proceeds of these sales were sent to help the war-stricken (Briot 98).

Poupelet met Anna Ladd through the American Red Cross and joined her in March 1918 to establish the Studio for Portrait Masks. Janet Scudder’s atelier became the epicenter of this studio and when Ladd returned to the United States, Scudder suggested that she would upgrade the atelier only if Poupelet was made manager, which never came about. Poupelet brought on board Robert Wlérick who had been working with facial surgery unit in Bordeaux. According to records of the American Red Cross (correspondence November 1918 to November 1920 and monthly report for October 1919), “Poupelet and Wlerick worked on a part-time basis of five hours a day, to enable them to pursue their own career as sculptors, for a salary of 450 francs a month” (Mitchell 53, note 35).

In his article on Poupelet, Eric Dussourt elaborates on her duties, which demanded more than fashioning masks, especially since she also had to manage the studio during Ladd's frequent absences, on visits to different hospital centers in France:

Jane Poupelet oversees the administrative and financial part of the business. Her job at in mask workshop is entirely voluntary and occupies her every afternoon, six days a week. She receives a monthly allowance of 400 francs for her professional purchases, without having the right to meals and accommodation like volunteer nurses (14).

When the studio was transferred to the Val de Grace hospital, Poupelet continued working on portrait masks until ca. 1920. For her contributions to the war effort, she was made Chevalier de la légion d’honneur in 1928. In addition, she joined the French League of Friends Animals, campaigning against vivisection and animal abuse (Briot 99).

Little is known about Poupelet’s specific activities and how she felt about her work:

She was anxious not to appear to have any definite political image. Having made sculptural practice the core of her life, she strongly believed that for a woman to make a successful career it was essential to force the critics out of their habit of confusing the image of the woman artist with her oeuvre. Accordingly, she put a veil of silence over her war work, as she did for all other events which she considered formed part of her personal life. […] Poupelet never considered the work she carried out for the Studio of Portrait Masks had formed part of her career as a sculptor. Nor did she feel it was her responsibility to use the practice of sculpture to commemorate the mutilated soldiers for posterity. When the American Red Cross offered a commission, she declined it. The portrait masks had been a form of personal engagement with history when history had left no alternative (Mitchell 47-48).

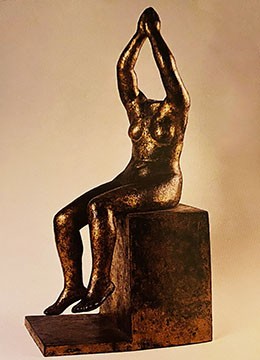

Jane Poupelet, "Femme Assise. Brooklyn Museum of Art.

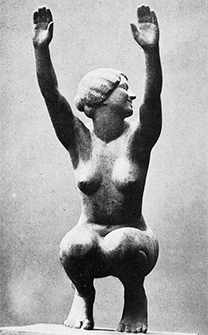

Jane Poupelet, "Imploration," 1928, gilded bronze. From Rivière, p. 100.

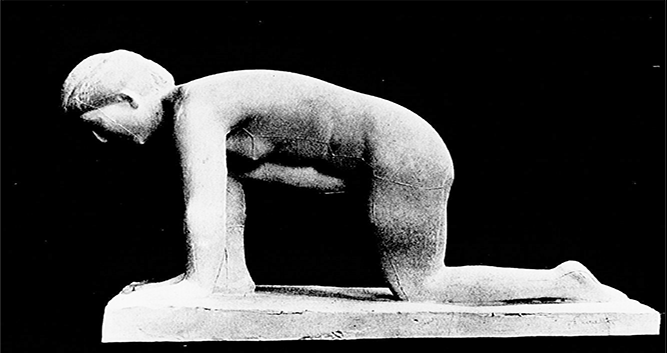

After the war, Poupelet continued sculpting in the same vein as she had before, the most notable difference being that she removed arms, hands, or heads from her figures (e.g., “Imploration” or “Femme assise”). While art historians claim she sought to “emphasize the form rather than the subject itself (Briot 81), on cannot help wondering if her experiences with disfigured soldiers had an impact on her work of if, indeed, she completely removed parts of the body that required details, preferring, as in her earlier sculpture, to push even further her focus on attitude, form, and movement.

In 1921, she was elected as President of the Société Nationale des Beaux-arts and exhibited at the 1922 and 1923 Salon (“Jeune fille baissée” and “Femme endormie”). In addition, she continued to advocate for women’s education, especially in the arts, and joined the International Federation of University Women, giving a paper on “French Feminine Art” at their 1922 inaugural conference, which took place at the Sorbonne and 4 rue de Chevreuse (Briot 92).

In 1923, she withdrew from the Société Nationale in complete disaccord with its old-guard ideology. Together with Edmond Aman-Jean, Antoine Bourdelle, Albert Besnard, Charles Cottet, Charles Despiau, Henri Lebasque, René-Xavier Prinet, Lucien Simon, and other avant-garde artists, they founded the Salon des Tuileries, where young artists were invited to show their work (G.-B. 18-19; Briot 109). The famed critic Louis Vauxelles echoed the dissenting voices in a caustic article describing the other Salons as “retirement homes for quavering tenors; not having been able to keep the young, they exhale an odor of decrepitude and mustiness (translated from the French, 2).

When she succumbed to pulmonary problems in 1925 (she was an inveterate smoker), Poupelet abandoned sculpture and limited herself to drawing. She nevertheless continued to exhibit her sculptures and drawings, and earned critical praise in both France and the United States. Several notable exhibits are worth mentioning:

- 1925: At the “Exposition Internationale des Art décoratifs et Industriels Modernes” (1925), she and four other sculptors associated with the “Société des peintres et des sculpteurs” (originally founded by Sébastien Mourey in 1899) were selected to represent five facets of French art: Jane Poupelet – grace, Louis Dejean – meditation, Charles Despiau – simplicity, Jean Halou –strength, and Robert Wlérick – suffering (Briot 74).

- 1928: she exhibited 11 sculptures and 48 drawings at the Galerie Bernier, with a catalogue written by Vauxcelles (Rivière 146).

Jane Poupelet, "Anesse à l'étable," n.d., ink drawing. From Kunstler, 1930, no. 15.

Jane Poupelet, "Vache," n.d., walnut stain and sanguine drawing. From Kunstler, 1930, no. 17.

According to Jacques Tcharny (2-5) of the Galerie Nicolas Bourriaud, Poupelet joined forces in 1931 with the animal sculptor Pompon, in creating the “Groupe des XII” at the Jardin des Plantes, where Pompon had brought together young animal sculptors who studied natural models. The group comprised: Pompon, Jouve, Guillot, Poupelet, Chopas, Margat, Hilbert, Profillet, Saint-Marceaux, Jouclard, Artus, and Lemard. It continued to be active even after the death of Poupelet in 1932 and that of Pompon in 1933, until the onset of WWII. Poupelet exhibited her “Anon” in the 1932 (April 8 to May 7) exhibition at the Hotel Ruhlman (3). A second exhibit took place at the Hotel Ruhlman in 1933 (March 1-31), where Poupelet was honored with a special display that also included Schnegg’s portrait bust (8). Her animal drawings shown at the Montross Gallery in New York (1931) were quite favorably reviewed by a critic of The New York times:

Jane Poupelet, well-known French sculptor, is the attraction at the Montross Gallery. This time drawings are most in evidence, and, as one would expect, animals predominate as subject matter. Apparently Mme Poupelet knows as much about cows as she does about horses. There are some miraculous cows in this show. Her studies of nudes hold their own, but it is the cows that really win your heart. We have yet to see them in the round, but no doubt that pleasure is in store. The small nude sculptures are not very impressive. One called “Imploration” [see above photo] will probably create a bit of a stir; it is persuasively gilded and no doubt every word that may be uttered regarding the sculptural soundness of every line is true; but why couldn’t the woman’s head have been somehow added? Without it she looks so forlorn, much more bereft than were she just a torso (Jewell 36).

Another critic’s perspective on the same exhibit is also worthwhile quoting for her innate understanding of Poupelet's gaze and technique:

Mme. Poupelet has a farm we are told, and goes there for her models, who cease to be models the moment she bends her sympathetic glance upon them. Sympathetic yet amused. Nothing quite downs that upwelling fountain of humor that finds the most legitimate avenues of escape – in the cocked-down ear of a rabbit, in the matinee hero aspect of an ox, long-lashed and sleepy-eyed; in the cocked-up tail of a duck and the pompous front of a pigeon. The drawings gossip of these differentiating attributes as country neighbors gossip of each other, on the basis of complete familiarity. The method used in the drawings is not unlike that of the sculptures. There is no attempt to say everything in one synthetic line. On the contrary, the rich sepia, sanguine, or ink emphasize bulk and fullness, giving the effect, the maximum of weight with a minimum of detail (Cary, 18).

Jane Poupelet died in Talence on October 17, 1932 and over one hundred artists organized a memorial service in her honor at the Église Notre-Dame-Des-Champs in Paris on December 19. Hundreds of articles in French journals and magazines extolled her drawings and sculptures, but only passing reference was made to her contributions to the war effort.

Poupelet's family donated 64 drawings and 15 sculptures (13 bronzes, 2 lead) to the Musée du Luxembourg, which had previously acquired two of her sculptures ("La Femme à la toilette" and "La vache marchant") and 3 drawings (de Laprade 4). The museum organized an exhibit of these works in January and February 1935, which prominently displayed Schnegg’s portrait-bust of Poupelet (Ladoué 43; de Laprade 4; Poulain 3). Many other exhibits in New York, Chicago, Paris, Bordeaux, Prague, Barcelona followed, including three large exhibits in Périgeux in 1949 the Musée Rodin in 1959, and the Musée Bourdelle in 1974.

In his obituary, art critic and journalist René-Jean (René Hippolite Jean) draws a most gracious portrait of Poupelet:

It is with stupor that artists will learn of the death of Jane Poupelet, who disappeared suddenly, in full force, when one could have expected to see her add to her work and enrich it for a long time. We will no longer see her, in her slim and small silhouette, a little boyish in appearance, cast an attentive eye during exhibitions. Silent and charming in her delicate features, often with a cigarette hanging from her lips […] A powerful sketcher and a delicate sculptor have disappeared. French art is in mourning (translated from the French, 2)

Sources

- “À la mémoire de Jane Poupelet.” Comoedia, 14 décembre 1932, p. 13. RetroNews.

- “À propos de Jane Poupelet.” Le Temps, 17 février 1935, p. 5. RetroNews.

- “Anon.” Catalogue des oeuvres. Musée d’Orsay.

- “Art Notes: Jane Poupelet's Sculptures on View at Theodore B. Starr's Gallery.” New York Times. 28 December 1913, p. 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Basler, Adolphe. “Une artiste de race. La revue mondiale, 1 mars 1931, p. 80-83. RetroNews.

- Bonnet, Marie-Jo. Les Femmes artistes dans les avant-gardes. Odile Jacob, 2006, pp. 37-44, passim. Google Books.

- Briot, Louise. “Jane Poupelet (1874-1932), une sculptrice engagée à l'orée du XXe siècle.” Mémoire Master 1 – Panthéon Sorbonne, 24 juin 2019. Academia.

- Campagnac, Edmond. “Femmes sculpteurs.” Le Matin, 8 avril 1934, p. 4. Gallica, BnF.fr

- Cary, Elisabeth. “Memorial Exhibition: Work of William Merritt Chase Is Shown-- Mme. Poupelet and Woman Artists' Group.” New York Times, 29 April 1928, p. XX18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Contrasts and Sculpture at the Academy.” The New York Times, 26 December 1915. Timesmachine.

- “Diplôme.” La petite Gironde, 25 mai 1892, p. 3. RetroNews.

- Dussourt, Eric. “Jane Poupelet (1874-1932), une artiste au service des gueules cassées,” Actes. Société française d'histoire de l'art dentaire, 2014, pp. 11-15. Biusante.parisdescartes.

- F.A. “Jane Poupelet.” Annales africaines, vol. 45, no.1, 1 january 1933, p. 11. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- G. B.J. “La grande querelle des salons.” Le Crapouillot, 16 juin 1923, p. 18. RetroNews.

- Gaze, Delia, Maja Mihajlovic, and Leanda Shrimpton, eds. Dictionary of Women Artists, Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997, vol. 2, pp. 1112 - 1114. Google Books

- Gersh-Nesic, Beth. “Whatever Happened to Jane Poupelet, Sculptresse Extraordinaire?” 20 November 2020. Bonjourparis.com

- Guillemot, Maurice. “Jane Poupelet.” Art et Decoration, vol. 34 Juillet-December 1913, 51-56. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Hamlin, Elizabeth. “Jane Poupelet Sculptor.” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 3, July 1933, pp. 53-56. JSTOR.

- Heguiaphal, Maia. “Jane Poupelet: Bronze, Paper and Commitment in WWI,” 4 February 2020, Daily Art Magazine.com

- “Jane Poupelet: Sculpteur.”Centre Pompidou.

- “Jane Poupelet catalogue.” Ministère de la Culture: POP

- Jewell, Edward A. “Art: 'Fifty Prints of the Year' Shown. Fiene Reveals a Color Sense. Poupelet's Cows Win One's Heart.” The New York Times, 3 March 1931, p. 36. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Kahn, Gustave. “Jane Poupelet.” L’Art et les artistes, vol. 21, no. 70, October 1926, pp. 79-84. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Kunstler, Charles. Jane Poupelet. Les Éditions G. Grès et Cie, 1930, 32 pp.

- Kunstler, Charles. “Jane Poupelet.” Ric et Rac, vol. 196, 10 December 1932, p. 5. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Ladoué, Pierre. “Musée du Luxembourg: Enrichissement 1934.” Bulletin des musées de France, vol. 7, no. 3, March 1935, p. 41-43. Gallica, BnF.fr

- Laprade de, Jacques. “Jane Poupelet.” Beaux-arts, 1 février 1935, p. 4. RetroNews.

- Lepoittevin, Anne. “Jane Poupelet: French Sculptress.” AWARE : Archives of Women Artists.

- “M. Huisman inaugure l'Exposition Poupelet.” Comoedia, 19 janvier 1935, p. 3. RetroNews.

- Maingon, Claire, “Homme blessé, corps mutilé: un thème iconographique de la grande guerre Akademos, 2015, pp. 75-83. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Martinie, H. “Jane Poupelet.” Art et Decoration, vol. 34 Juillet – December 1924, vol 46, p. 87-96. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Mitchell, Claudine. “L’horreur en face.” Catalogue exposition Jane Poupelet à Roubaix, Gallimard, 2005. Pp; 56-77.

- Mitchell, C., “Inventaire des plâtres du studio Jane Poupelet.” Musée Despiau-Wlerick a Mont-de-Marsan, 1992, pp. 32-35.

- Myra, Andrée. “Artistes Girondins: Mlle Jane Poupelet.” La petite Gironde, 19 septembre 1903, p. 1. RetroNews.

- Pays, Marcel. “Mme Jane Poupelet: Sculpteur.” Le Radical, 17 juin 1913, p. 4. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Placin-Gea, Amandine. “La ‘bande à Snegg’: examen d’un groupe de sculpteurs indépendants.” Histoire de l’Art, no. 53, November 2003, pp. 45-55. Persée.

- Poulain, Gaston. “La mémoire de Jane Poupelet est honorée au Musée du Luxembourg.” Comoedia, 17 janvier 1935, p. 3. RetroNews.

- René-Jean, “Un grand sculpteur, Mme Jane Poupelet est morte.” Comoedia. 23 November 1932, p. 2. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Rivière, Anne, ed. Jane Poupelet (1874-1932). Gallimard, 2005, 166 pp.

- T. S. “Au musée du Luxembourg: sculptures et dessins de Jane Poupelet.” Le Temps, 13 février 1935, p. 4. RetroNews.

- Tachon, Franny. “Poupelet Jane.” Les musées en France.

- Tcharny, Jacques “Catalogue Exposition Groupe des Douze." Galerie Nicolas Bourriaud, June 5-July 18 2020. Issu.

- The Paris Times, 17 August 1924. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- “Un service funèbre.” Figaro, 22 décembre 1932, p. 2. RetroNews.

- “Une centaine d’artistes assistaient hier au service à la mémoire de Jane Poupelet.” Comoedia, 20 décembre 1932, p. 3. RetroNews.

- Vauxelles, Louis. “Le vernissage des salons des « Artistes français et de la société nationale.” L’ère nouvelle, 30 avril 1924, p. 2. RetroNews.

- Waldemar, George. “L’Actualité artistique: In Memoriam Jane Poupelet.” La Revue mondiale, 1 mars 1933, pp. 67-70. RetroNews.

- Wapler, V. “Jane Poupelet Sculpteur,” Mémoire de Maîtrise, Université de Lille III, 1973, Catalogue Raisonné, no. 61, pp. 212 -13.

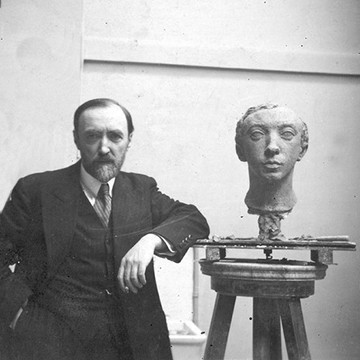

Robert Wlérick

Robert Wlérick with the head of the sculptor Raymond Corbin. n.d. Photograph. Retrieved from Roudié, p. 14.

Musée Despiau-Wlérick in Mont de Marsan, France. n.d. Photograph. Retrieved from Alienor.org.

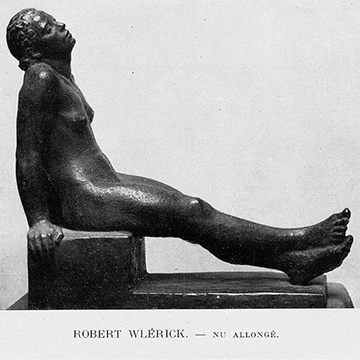

Robert Wlérick, "Nu Allongé," bronze. n.d. Photograph. Retrieved from Kahn, p. 44.

Robert Wlérick was a prolific sculptor (see catalogue); a museum (inaugurated on July 21, 1968) is dedicated to his work and that of his friend, Charles Despiau, in their hometown in Mont-de-Marsan, France; numerous articles and catalogues are devoted to his sculptures and drawings, yet not much is known about his life. As with Poupelet, elements can be pieced together from mainly secondary sources; both were uniquely discreet, never really seeking the limelight, especially when it came to their contributions to the war effort. In the words of Gustave Kahn: "His life has no anecdotes. He has no biography, only a list of works, one which gets richer every year" (45).

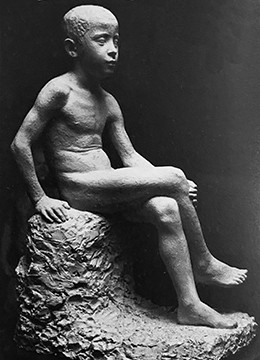

Robert Wlérick, "Enfant aux sabots," before 1906. Photograph. Retrieved from Facebook, Société des amis du Musée Despiau-Wlérick. This is the only sculpture remaining from his early training.

Born on April 13, 1882 in Mont-de-Marsan, France, Wlérick was bound for an artistic career early on. His father, like his Belgian grandfather, was a woodworker; he owned a furniture store and sold antiques. By the age of 15, Wlérick assisted in the family business, leaving the Lycée Victor Duruy, where, like Charles Despiau, he had followed the drawing classes of Louis Henri Ismaël Morin. The latter had detected his gift for sculpting and continued giving him lessons even after he left school. His plaster statue “Enfant aux sabots” is the only piece from this early period that he did not destroy. It was gifted by Morin to the Despiau-Wlérick museum, after Wlérick’s death in 1944.

In 1899, Wlérick entered the École des beaux-art in Toulouse, where, for five years, he studied sculpting under Jean Alexandre Falguière (Ackerman 13), mainly on wood (Kahn 45). After his military service, he went to Paris in 1906, where, through his friend Despiau, he joined forces with the “bande à Schnegg.” After several trips back and forth between Paris and his home, he settled in 1908 on rue Dutot in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, close to the atelier of the Schnegg brothers, and several doors down from Jane Poupelet. In the summer months, he would return to Mont-de-Marsan where he had an atelier on his family's property. He shied away from training at the École des beaux-art, preferring to observe and sketch at the Louvre.

Robert Wlérick, "Le petit landais," plaster. 1906. Photograph. Retrieved from Roudié, p. 32.

Robert Wlérick, "La petite landaise," bronze.1911. Photograph. Retrieved from roubaix-lapiscine.com/.

Robert Wlérick, "La petite jeunesse," bronze. The model is Georgette Wlérick, his wife. The first version, in half size, was presented at the Salon national de la Société des beaux-art in 1913. A second version, also in half size, with drapery under the left arm, was on display at the Salon des Tuileries in 1927. The 3rd version was life-size and without the drapery. Photograph. Retrieved from La Fondation Coubertin.

Robert Wlérick, "Madame Robert Wlérick," bronze with black and blue patina. 1913. Photograph. Retrieved from Roudié, p. 29.

His earliest showing seems to be "Le petit landais" in 1907 at the Salon of Société nationale des beaux-arts. From then on, he showed regularly in different Parisian galleries and salons. His atelier was at 14, rue François-Guibert, not far from painter and sculptor Berthe Martinie (Roudié 16), spouse of the journalist and art critic Henri Martinie who wrote several articles about Wlérick's work in 1928 and later in 1948.

In 1913, Wlérick married Georgette Aldric who modeled for him and with whom he had a son and two daughters. That same year, he began teaching at the Germain Pilon school, which was interrupted by the outbreak of WWI.

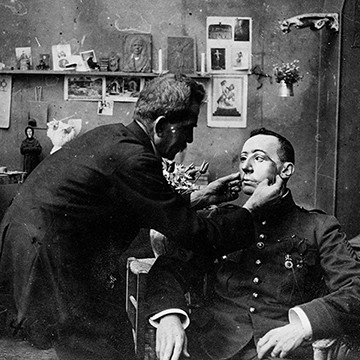

Robert Wlérik adjusting mask made by Mrs. Ladd for French soldier whose face was mutilated in the war. August 1918. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017682140/>.

Trying on Mask Just Before It Had Been Painted. July 1918. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2007676073/>.

He was mobilized into the French military in 1914, and from 1915 to 1918, he worked in the facial surgery department of Bordeaux, instituted by doctors William Dubreuilh and Émile-Jules Moure. In 1916, Moure consolidated all the services that restored wounded faces, concentrating not only on external but also internal wounds. In order to document and assist in the different stages of the restorations, he also created several workshops led by artists: for drawings and watercolors, Jean Dupas (Grand Prix de Rome 1910) and Christian Guindet; for sculpting molds, Robert Wlérick, Edmond-Ernest Chrétien, and Charles Hairon; for photography and stereoscopy, Jean Séréni (The Val-de-Grâce museum preserved some of examples, Portmann).

Wlérick was drawn to the Studio for Portrait Masks, by Jane Poupelet, and continued working with Poupelet when the Studio moved to the Hôptial du Val de Grace. He stopped sometime in 1919. Other than Junka's article, "Le masque de gloire," describing his visit of the studio with Wlérick, we have found no sources highlighting his work at the Studio itself.

Robert Wlérick, Monument to the dead 1914-1918, Labrit, France. Photograph. Retrieved from Wikepedia.

Robert Wlérick, Monument to the dead 1914-1918, Saugnacq-et-Muret, France. Photograph. Retrieved from monumentsmorts.univ-lille.fr/.

Robert Wlérick, Monument to Maréchal Foch, begun in 1939 by Wlérick and completed by Raymond Martin after Wlérick's death. Photograph. Retrieved from statues.vanderkrogt.net/.

Robert Wlérick, Monument to those who died in 1914-1918, Morcenx, France. Photograph. Retrieved from 40110morcenx.wordpress.com/.

After the War, Wlérick, received commissions to sculpt war memorials in different French towns (Labrit, Morcenx, Saugnacq-et-Muret), and he continued showing his plasters and bronzes in different Parisian salons and galleries.

Between 1922 and 1943, Wlérick taught at the École des arts appliqués à l’industrie (the fusion of the Germain Pilon and Bernard Palissy schools). In 1923, he participated, with Bourdelle, Despiau, Déjean, Halou, Maillol, Pompon, and Poupelet, in the creation of the Salon des Tuileries, leaving the Société nationales des beaux-arts. He built an atelier in the 20th arrondissement of Paris (Roudié 17), far from the madding crowd of Montparnasse. Yet he was still part of the Montparnasse scene, since he replaced Bourdelle in 1929 at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière (Fondation Coubertin).

Wlérick was named "Chevalier" of the French Legion of Honor in 1926. In the 1930s, he traveled to Italy, and built a vacation home in the Landes (Roudié 18). He participated in the 1937 Exposition universelle, with three commissions: "Pomone," "Zeus," and "L'Offrande," each dedicated to a particular pavillon on the exhibition grounds (Fondation Coubertin).

Robert Wlérick, portrait of the sculptor Corbin, patinated plaster? 1932. Photograph. Retrieved from Kahn, p. 48.

Robert Wlérick, portrait of Lydie Paquereau, patinated plaster? 1929. Photograph. Retrieved from Kahn, p. 48.

Robert Wlérick died of illness and deprivation on March 7, 1944, just as he was about to complete a commission for a memorial to General Foch. The memorial was finalized by his disciple and co-worker Raymond Martin.

Wlérick’s wife continued to promote his work and participated in organizing a major retrospective of his works with the painter Maurice Boitel at the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts in the 1960s. In 1994, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Wlérick's death, four French museums, including the Bourdelle museum in Paris and the Mont-de-Marsan museum organized an exhibition devoted to his studies, sketches and drawings. The main works of Wlérick are exhibited at the Museum of Mont-de-Marsan, along with those of Charles Despiau and other sculptors.

Robert Wlérick, "Pomona." 1936. Photograph. Retrieved from La Renaissance, p. 32.

Sources

- Ackerman, Ada. "Redonner visage aux gueules cassées. Sculpture et chirurgie plastique pendant et après la Première Guerre mondiale." RACAR: revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 2016, vol. 41, no. 1, 2016, pp. 5-21. JSTOR.

- “Exposition d’archives et de documents de guerre, d’oeuvres d’artistes mobilisés au Centre d’O.R.L. et de Chirurgie maxilo-faciale, 12 april-1 juin 1919.” Terrasse du Jardin-Public, Bordeaux. Gallica. BnF.fr

- Haurie, Béatrice. “Robert Wlérick.” Bulletin des Amopaliens landais, June 2009, pp. 13-14.

- Junka, Paul. “Le masque de gloire.” La Renaissance, vol. 7, no. 7, 29 March 1919, pp. 9-12. Gallica, BnF.fr

- Kahn Gustave. “Robert Wlérick.” L’Art et les artistes, vol. 28, no. 141, November 1933, pp. 44-49. Gallica, BnF.fr.

- Marquis-Sébie, Daniel. "Robert Wlérick, Critique à l'atelier de sculpture de la Grande Chaumière." Revue des Arts, vol. 10, no. 159. August 1931, p. 12. Gallica. BnF.fr.

- Placin-Gea, Amandine. “La ‘bande à Snegg’: examen d’un groupe de sculpteurs indépendants.” Histoire de l’Art, no. 53, November 2003, pp. 45-55. Persée.

- Portmann, Didier. "Émile Moure Pionnier de l'ORL moderne dès 1880." Première Journée d'histoire. de l'oto-rhino-laryngologie 20-21 novembre 2009. Biusante.parisdescartes.fr.

- "Robert Wlérick." Fondation Coubertin.

- Roudié, Paul. Robert Wlérick (1882-1944), catalogue for the 1982 Musée Rodin and Musée Despiau-Wlérick retrospective exhibitions.