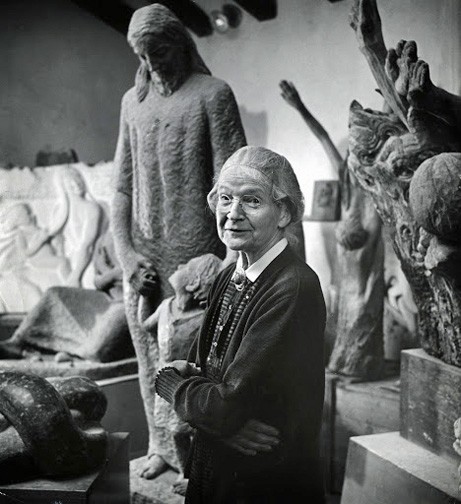

Grace Hill Turnbull, 1880 – 1976

Painter, sculptor, author, poet, and advocate for human rights and temperance Grace Hill Turnbull was born into a "literary and prosperous Victorian family" on December 30, 1880 in Baltimore, Maryland (The Sun, Sept. 21, 1980, D6). Her father, Lawrence Turnbull, a lawyer and realtor, had once served as the editor of Southern Magazine, and her mother, Francese Hubbard Litchfield Turnbull, was the first president of the Women's Literary Club (founded in 1890), an author of “several historical romances” (The Art Digest, October 15, 1931, 6), and a patroness of the arts.

The Turnbull home in Baltimore was "[...] a center of such poets as Sidney Lanier, such celebrities as Johns Hopkins, Dr. Gildersleeve, and others" (Muller 7). One of Grace's brothers, Edwin Litchfield Turnbull, was a musician who was instrumental in the establishment of the Johns Hopkins University Orchestra and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. He composed or arranged many musical scores, including 1901’s “Farewell to Nancy,” with text by Robert Burns and “a very attractive cover” designed by his artist sister (The Sun, October 27, 1901, 8).

Turnbull's artistic production was vast and eclectic, ranging from portraits (including miniatures on ivory) and conventional and abstract landscapes to small and large-scale sculptures in bronze, clay, wood, marble, and stone, including female water fountains, animal figures, and religious characters. Her freedom of expression knew no bounds since, as she acknowledged in a number of interviews, she did not have to earn her living from art. She was a singular, outspoken, and deeply religious individual who used her money and reputation to further the arts and the social welfare of young people and the poor.

Turnbull demonstrated her creative talent as a child. Encouraged by her family, she attended art classes at an early age, working mainly with pastels: "[I] did not want to take the time to stop to wash my brushes and hands, as I would have to do if I used oils or water colors, and so my teacher, to humor me, gave me pastels to work with. I have kept up the practice of using them to some extent until now" (L.C.A. 6). And although she claimed she just "learned around," Turnbull trained with several influential mentors.

Her family spent many summers in New England, where she studied with landscapist Willard Metcalf. She trained at the Maryland Institute College of Art, where she also served as an assistant to Philadelphia portrait and genre painter Thomas P. Anshutz. Grace claimed that she learned the most about painting in those three years. Turnbull then studied for five months with Joseph De Camp at the Art Students League in New York, spent another five months with Ephraim Keyser in Baltimore, and yet another five months with Sir Moses Ezekiel in Rome in 1902. There were also three months at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, training under William Merritt Chase, with some lessons from Cecilia Beaux: "I am not sure that Cecilia Beaux helped me much. Her class was very crowded and she had only about a half a minute to give to each of her pupils" (L.C.A. 6).

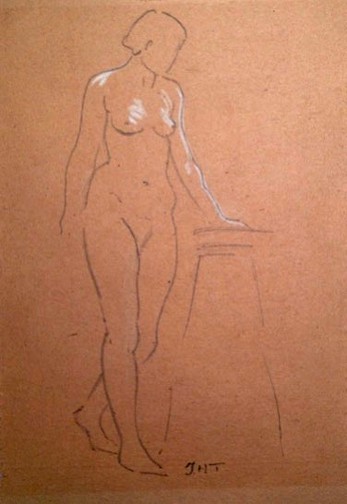

In pursuit of a complete art education and despite her conservative upbringing, Turnbull decided to take a life class in which she could study from a nude model:

Mother's objection I felt I could overcome […] but she told me solemnly that if I carried out my intention of working in a life class it would kill Father […] I decided that I must take my life into my own hands then or never. As a matter of fact, my joining the life class appeared to have no malignant effect whatever upon my father (cited in Dorsey n.p.).

Her first exhibitions were at the Arundell Club in March 1907, where she showed portraits and miniatures (The Sun, March 19, 1907, 7) and at the Maryland pavilion of the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, where she showed miniatures on ivory (The Sun, January 7, 1966, B5). In 1908, Turnbull was among the many talented Maryland artists in the Baltimore exhibit of plastic arts organized under the auspices of the National Sculpture Society (The Sun, April 12, 1908, 16). She also was among the exhibitors at the New York Water Color Club show in 1909, along with future Girls’ Art Club affiliates Lee Lufkin Kaula and Mary Van der Veer. Turnbull’s “large pastel portrait” (subject unknown) was praised for its “low tones” and the seriousness with which the pastel medium was treated (Cary 36-37). She also exhibited at the Washington Water Color Club in February 1909 and her pastel of a child was “[…] of such distinguished merit that it cannot be passed without note. It is strongly modeled, excellent in tone and insistent with personality” (American Art News, February 27, 1909, 2). The Charcoal Club also showed several of her miniatures in February 1910 (American Art News, February 19, 1910, 2).

The Sun published a lengthy interview with Turnbull in 1912, when she was just establishing herself professionally as an artist. It focused mostly on her skill at portraiture and how she worked to make her sitters comfortable in the studio, but it also revealed Turnbull’s humility and self-effacing nature: “‘You see, there is not a thing to say about me,’ she declares, in farewell. ‘I have had a scrappy sort of an art education, with no adventures of any sort to make it interesting’” (L.C.A. 6).

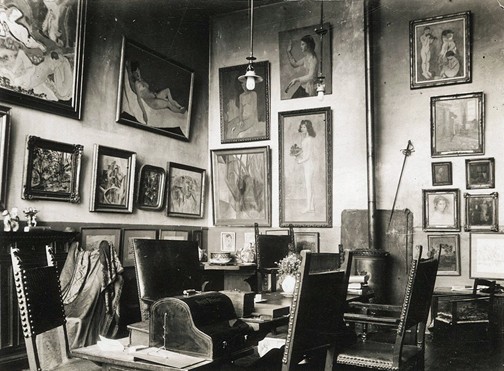

Nonetheless, she did pursue adventures, and despite insisting that "[...] it is not necessary now to expatriate oneself to study art. We have excellent schools in this country. None in the world is better than the Philadelphia Academy" (L.C.A. 6), she traveled to France, Germany, and Italy the year before WWI. She resided and had a studio at the Girls' Art Club from about October 1913 until at least March 1914.

Like so many other American women artists in Paris, Turnbull visited Gertrude Stein, having been introduced by Ephraim Keyser, the Baltimore sculptor with whom she once studied. She described the encounter at Stein's salon, which, in her case, was unpleasant

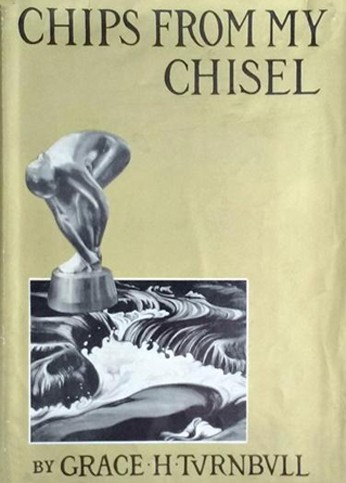

Ephraim Keyser... had given me a letter of introduction to his niece Gertrude Stein who was then living there, and fortified by the possession of this document the two girls and I undertook to storm the lioness in her den, choosing for the purpose one of her evenings at home. We were at once translated into an atmosphere terrifyingly transcendental. Gertrude, a monumental figure in a dark monkish garment free-flowing from the neck, after rising to meet us, returned to her sofa and her large black cigar; glancing over the note of introduction, the oracle uttered these remarkable words: "Well, look around, won't you." We did. That was all we could do, for the strange, exotic, short-haired women and long-haired men milling about in a mute mystic haze had not a motion to rescue the three young Americans from their predicament, equally strange as we were to them by virtue of mere normality. On the walls were a number of early Picassos, circus folk of the blue period, and other paintings, post-impressionistic, cubistic, etc., new to us then as to the world; but they couldn't hold us indefinitely; and when Margaret, the bravest of our crew, attempted to address one of the transcendental beings and met with no response from her, our only resource seemed to be to withdraw from the assembly presences so little desired (Chips From My Chisel 34).

A decidedly traditional artist, Turnbull did not embrace modernism. Even in her seventies, she still decried the likes of Matisse, fiercely objecting to his "Blue Nude" because "[...] the human face and form have been subjected to such indignities with no compensatory gain in pure design or color" (cited in Dorsey, n.p.).

In Paris, she exhibited at the Salon des Beaux-Arts in 1914, at the American Woman’s Art Association at 4 rue de Chevreuse, and at the International Art Union, where she received the Whitelaw Reid Prize in 1914 for the oil stain "Mother and Child," which had been identified as "Twilight" or "Crépuscule" at the Salon des Beaux-Arts (J.M.M. 646). In a letter dated February 21, 1914 that she reproduced in her 1953 autobiography, Chips From My Chisel, Turnbull wrote:

Why they should have taken it into their heads to single out my insignificant, subdued, old-fashioned Mother and Child in its dull frame to hang in the central position in the Club Gallery seems strange enough: but why to this insult they should add the further injury of awarding to it the first prize of 1000 francs ($200), remains an unsearchable mystery (39).

After a brief trip to Brittany, Turnbull sailed for the U.S. on September 23, 1914, where she prepared to eventually join the war effort in France, although she was a committed religious pacifist.

After several failed attempts, she finally made it to France as a Red Cross volunteer in August 1918. She was employed as a "Searcher [...] writing to relatives of soldiers who had died and identifying missing men" (Anson TM15):

"I used to get flowers from French home gardens to place on the orange gravel graves of the boys and, slipping one of the few flowers I would send that back in the letter to the mother, as there was so little to tell that would comfort" (cited in Muller 7).

When the war work finally ended, she boarded a military ship in Brest on April 16, 1919 and arrived in the U.S. on April 25, immediately resuming her artistic activities.

A review in The Sun of her 1919 show at Baltimore's Peabody Gallery praised the diversity of her encounters and her intimate connections with the subjects of her paintings:

She is an artist who has lived sympathetically among those whose portraits she paints—in Italy where every street corner furnishes a picturesque Latin model; in Spain among the people; in Brittany among peasant children who attend convent schools and kneel before sea coast Calvaries. She knows Paris models and Holland peasants; she has talked with and painted sailors from the Azores, and to slip into the Peabody Gallery for a quiet hour with Miss Turnbull’s paintings and spirited modeled studies, is to feel that her genius has introduced you to many interesting and picturesque people who have passed in and out of her own life (E.E.L. SM3).

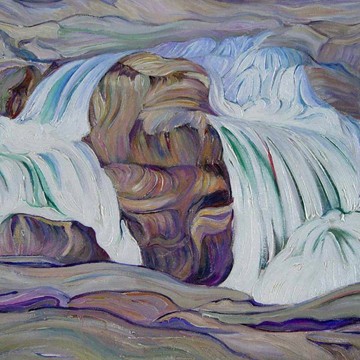

Turnbull continued to travel extensively, to Bermuda (1920), the West Indies (November 1921- February 1922), the Grand Canyon (1923), Woodstock (1925), Mexico (1929), Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Greece, and Italy (1936). Her exhibition pieces reflected her varied experiences around the world. She showed several of her decorative paintings of Bermuda and the West Indies at the Peabody Gallery in 1920 and 1922. Both shows were reviewed very favorably in The Sun. The first lauded her colorful renditions of nature and her minute life studies made in Paris (E.E.L., November 14, 1920, MA12). The second qualified her work as modern style:

The word impressions conveys very accurately the mission of the pictures to the eye of the beholder. They are painted with strength and boldness after the modern decorative style that is, in truth, a return to the ancient art of Japan that strives for effective and realistic impressions rather than exact imitations of nature (E.E.L. November 19, 1922, P2SN18).

In 1925, she exhibited several paintings at Arundell Hall in Baltimore, ranging from conventional flower paintings to abstractions. The critic of The Sun commended her for putting "[...] more dynamite into a square inch of pigment than many artists can conjure out of half a dozen barrels of it" (H.K.F. 11).

Turnbull never married. After the death of her mother in 1927, she designed a grand, eccentric Baltimore home with her architect brother Bayard, who was just sixteen months older than Grace. The two were close and had already tried their hand at building together as children. When she was 13 years old, they had erected a miniature marble church, topped by a six-foot tower, in the backyard of their home (Anson TM15). Sculpting came naturally to Turnbull as she was building her home and studio, which she decorated with 12-foot totems replete with carved religious imagery:

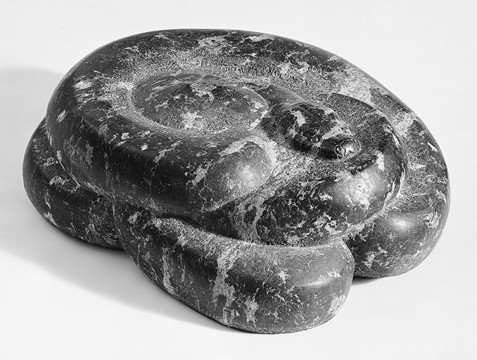

"..we set about planning the house, my brother Bayard and I; for it was to be a homemade house, even to the architect, a house Spanish in feeling, with a hint of Bermuda about it too. The living room, two stories high, with a balcony running around the interior, was suggested by the Cervantes Inn in Toledo. As fancywork during the last months I had carved a nine-foot refectory table [...] and while the house was building I cut designs on certain beam-ends and an inscription on the lintel of the front door [...] (163-164). The corners of the house presented tempting locations for tree-trunk carvings fitted to them [...] I carved a St. Francis Preaching to the Birds [...]" (165). St. Francis was followed on other corners of my house by Christ Touching a Dead Soul to Life, a Madonna and Child and a Flight into Egypt [...] Other emplacements in the garden invited stone sculptures of a Squirrel, a Sleeping Swan [...] (Chips From My Chisel 167).

The house was completed in 1928, and she remained in her temple of creativity until her death, turning to sculpture and writing as the primary foci of her artistic expression:

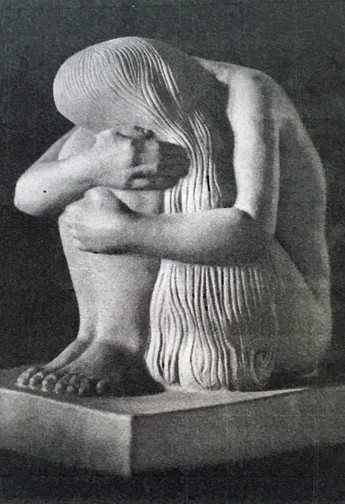

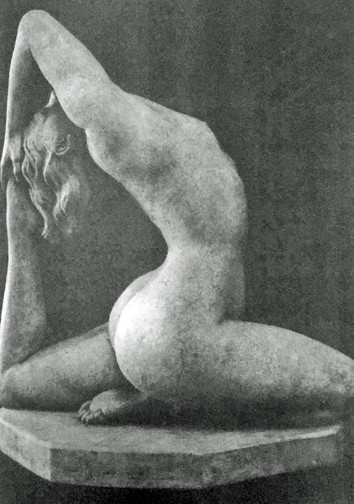

Upon settling in my new house I ceased altogether to paint and took instead to sculpture which I believe is my more native bent. I have never had any instruction in the cutting of wood or stone [...] I think by actually doing one can learn a great deal. After trying my wings on the first stone carving, I [...] used the 'taille directe' method, cutting directly into the marble or wood with only a sketch a few inches high to guide me (Chips From My Chisel 167).

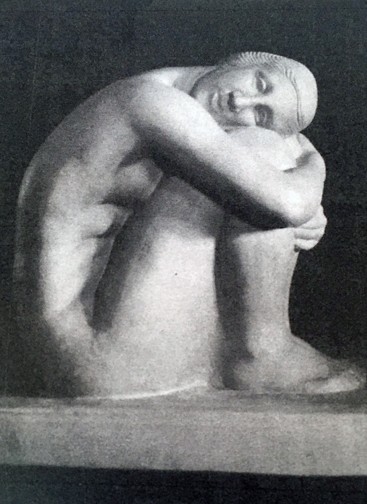

Turnbull had studied sculpture at the Rinehart School of the Maryland Institute and with Moses Ezekiel in Rome in 1902. Though she did have this formal training, she is often identified as "essentially self-taught" (J.M.M. 646). According to Elizabeth Stevens, "it was not until she was about 50 that she began to concentrate in earnest on the sculptures which were to be the major achievement of her life [...] it was with sculptures of single nude figures - and of single animal figures as well - that Miss Turnbull was to achieve her best works" (The Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1980, D6).

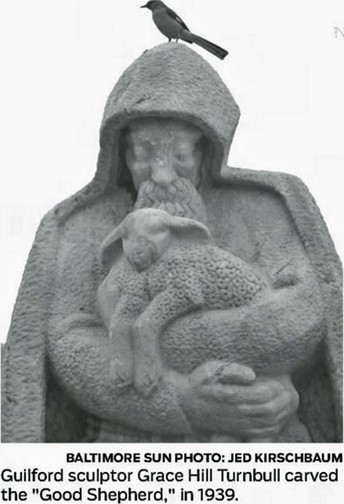

After the death of her friend Lizette Woodworth Reese in 1935, Turnbull was asked to create a monument honoring the poet and teacher. The idea for the design came to her upon returning from a trip around the Mediterranean (1936-1937) and was inspired by a recurrent theme in Reese's poetry, a shepherd and his fold.

She described the complex creative process in her autobiography, Chips From My Chisel:

I ordered from Georgia the necessary blocks of its native pink marble, and from the half-scale plaster model I made, the stone-cutters began work in Rullman and Wilson's marble-yard; for the figure of the Shepherd was to be over life-size and the whole group much too large to be accommodated in my own studio. So amid the deafening din of electric saws, pneumatic drills and iron hammers, the roar of traveling cranes on the runway overhead, and the screeching of the surface-finishing machine we chiseled away [...] (233-234).

The memorial, entitled "The Good Shepherd," stands on the old grounds of Reese's alma mater, Eastern High School in Waverly. “On the base beneath the bench is carved the poem ‘Come Every Helplessness’” (Ziegler 141). Reese was known to Turnbull through her parents- her father had published one of Reese’s earliest poems in The Southern Magazine when she was just seventeen, while her mother, president of the Woman’s Literary Club of Baltimore, befriended Reese and hosted many dinner parties in her honor at the family home. (Turnbull, 1966, 9-10).

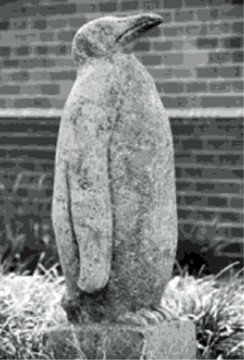

According to the inventory of her papers at Syracuse University, Turnbull's "paintings and sculptures were exhibited at a number of solo shows, including the Delphic Studio in New York (1931, 1946) and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. (1948).” She also participated in many group shows, at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the International Art Union in Paris. A large solo show of Turnbull’s works opened in January 1966 at the Baltimore Junior College Art Gallery. The Baltimore Sun published a brief notice and quoted the exhibition catalogue’s foreword by Bernard Perlman, head of the Baltimore Junior College Art Department: “In all her art work, this warm and wonderful woman transmits her love for her subject matter, be it a painted figure composition of a mother and child or a landscape with lush tropical foliage, a sculpted religious or secular figure, or the study of a penguin or python” (B5).

Turnbull won several prizes for her work: a plaster torso received the Anna Hyatt Huntington Prize at the National Association for Women Artists (1931) and the first prize and silver medal at the Maryland Institute Alumni Show (1932); her fountain figure received the first prize in the Women's Achievement Exhibition (1932) and an honorable mention from the Palm Beach Art Center, Florida (1935).

Throughout adulthood, Turnbull followed her parents’ lead and lived a fairly conservative life. According to her relatives, she was "[...] as severely disciplined as if she had been under the rule of a convent (The Baltimore Sun, December 29, 1976, C1). She was “as committed to abstinence as to art” and was a fervent advocate for temperance; apparently, she “never served anything stronger than apple juice” (Dorsey) and opposed the use of tobacco, alcohol, coffee, tea, and soda. She lived so frugally that she mowed her own lawn, drove a 1937 Ford convertible for her entire life, and ate “only of the foods that were good for her, never for the relish of eating” (The Baltimore Sun, December 29, 1976, C1). In other ways, Turnbull was quite progressive, vehemently opposing segregation, championing educational efforts to support African Americans, and assisting young artists in their endeavors with funds and visits to her home.

An inveterate writer, Turnbull used pen and ink to express her spirituality and advocate her firm opinions on art and life. She communicated her thoughts in exhibition reviews and letters to the editor of regional newspapers. In her appraisal of a show at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1924, for example, Turnbull made the case for the role of art museums in society:

The museum of art is as necessary to the welfare of the community as the library or the concert hall, and while there is a dangerous tendency in our older art museums to become mausoleums of art, ‘conventicles of tradition,’ there is one at least in the town of Santa Fé that sets before the public, in a series of more or less transient shows, the most vital native art of today, including that of the American Indian (Art and Archaeology 70).

In 1929, she published Tongues of Fire, an anthology on non-Christian religions. In 1934, she published an Oxford University Press translation of the work of philosopher Plotinus, The Essence of Plotinus, on which she had worked in seclusion for three full years. Although she was already proficient in French, German, and Italian, Turnbull had taught herself Greek in order to read and translate the original. In the 1950s, she published a book warning of the dangers of alcohol, Fruit of the Vine (1950), as well as her autobiography, Chips from My Chisel (1953), and a work of fiction, The Uncovered Well (1954), in addition to her theories on painting and sculpture, Art Book (1959).

Grace Hill Turnbull died of a circulatory disease at the age of 96 in 1976. After a lifetime of generosity and philanthropy, her final act of charity was to bequeath her studio-house as well as a collection of artworks to the Maryland Historical Society, "with the stipulation that 'the premises be kept intact as far as possible' and perhaps even exhibited "as a memorial to my family and me'" (Guntz).

In 1980, the exhibition "Selections from the Bequest of Grace Hill Turnbull" was installed in the main galleries of the Maryland Historical Society to celebrate the 100th anniversary of her birth and honor "her efforts to promote the careers of Baltimore artists (The Baltimore Sun, May 25, 1980, T13). In a critical appraisal of the exhibition, Elizabeth Stevens derided Turnbull's work as derivative, conservative, and sentimental; she claimed that her outlook was too fragmented "to foster the transformation of Miss Turnbull from a talented amateur into a mature artist capable of steadfastly exploring a comprehensive vision" (The Baltimore Sun, September 21, 1980, D6).

We beg to differ and choose instead to honor Turnbull’s humble self-assessment: “‘I am no Michelangelo […] I have done the best with what I had” (Anson TM15).

Epilogue: In the summer of 2008, the Maryland Historical Society relinquished all rights and responsibilities to the Turnbull property. PNC Bank has auctioned off the contents of the house and sold the property to Douglas Hamilton Jr., the chief executive officer of a local manufacturing company and a trustee of the Walters Art Museum. After spending "six figures" to renovate and reconfigure it with the help of architect James R. Grieves, the Hamiltons made it their home in 2011.

Sources

- Anson, Cherrill. “Freeing Shapes from Wood and Stone.” The Sun, June 12, 1960, p. TM15. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Baltimore." American Art News, February 19, 1910, vol. 8, no. 19, p. 2. JSTOR.

- Bodine, A. Aubrey. Original Vintage Photograph of Grace Hill Turnbull, 1937. aaubreybodine.com.

- Cary, Elisabeth Luther. “The Exhibition of the New York Water Color Club.” Art and Progress, vol. 1, no. 2, December 1909, pp. 35-37. JSTOR.

- The Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation-Staff Report. Landmark and Special List Designation Report, Grace Turnbull House, 223 Chancery Road, Baltimore, Maryland. November 18, 2008.

- Dorsey, John. “Grace Turnbull: An Artful Life.” The Baltimore Sun, May 26, 1996.

- E.E.L. "Miss Turnbull's Work, Now Showing at Peabody." The Sun, November 14, 1920, p. MA12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- E.E.L. "Modern Style Marks Work of Grace Turnbull." The Sun, November 19, 1922, p. P2SN18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- E.E.L. “Peabody Has Important Exhibition of the Work of Grace H. Turnbull.” The Sun, November 23, 1919, p. SM3.

- "Few Extremes in Salon: Grace H. Turnbull, of Baltimore, Among the Many Women Exhibitors."

- The Sun, Apr 12, 1914, p. 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Grace Hill Turnbull Papers, Syracuse University Libraries.

- “Grace Turnbull Exhibition.” The Sun, January 7, 1966, p. B5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Grace Turnbull, sculptor, crusader, dies.” The Sun, December 29, 1976, p. C1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Guntz, Edward. "From Preservation to Desperation." The Baltimore Sun, November 1, 2008, p. A.1. ProQuest.

- H.K.F. "Grace H. Turnbull Exhibits Paintings At Arundell Hall." The Sun, February 10, 1925, p. 11. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- J.M.M. "Grace Hill Turnbull (1880-1976)." American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born between 1865 and 1885, eds. Lauretta Dimmick, Donna J. Hassler. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999, pp. 646-647.

- Kelly, Cindy. Outdoor Sculpture in Baltimore: A Historical Guide to Public Art in the Monumental City. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- L.C.A. “A Baltimore Artist and How She Learned to Make Portraits.” The Sun, February 7, 1912, p. 6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Miss Turnbull as an Artist." The Sun, March 19, 1907, p. 7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Muller, Amelia. “New Carved Walnut Column Soon to Adorn Author’s Home.” The Sun, January 13, 1941, p. 7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “New Song by Mr. Turnbull.” The Sun, October 27, 1901, p. 8. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Notable Maryland Artists and Example of their Work." The Sun, April 12, 1908, p. 16. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “A Painter With a Literary Background.” The Art Digest, October 15, 1931, p. 6. Google Books.

- "Sculptress Awarded Prize At Maryland Institute Show." The Baltimore Sun, March 7, 1932, p. 5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Stacks, Richard. Photo of Turnbull in her studio, June 12, 1960. The Baltimore Sun, February 15, 2013.

- Stevens, Elisabeth. "Grace Turnbull: too comfortable to be great?" The Baltimore Sun, Sep 21, 1980, p. D6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Tholles, Thayer, ed. American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Art Museum, volume II, a catalogue of Artists born between 1865 and 1885. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

- “Turnbull bequest honors centennial of her birth.” The Baltimore Sun, May 19, 1980, p. B6. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Turnbull exhibit shown by Historical Society." The Baltimore Sun, May 25, 1980, p. T13. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Turnbull, Grace Hill. Chips From My Chisel: An Autobiography. Rindge, New Hampshire: Richard R. Smith, 1953.

- Turnbull, Grace H. “Exhibition of Sculpture by American Artists.” Art and Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 1, January 1924, pp. 67-70. HathiTrust.

- Turnbull, Grace H. “Miss Reese and Her Loyal Critic.” Menckeniana, no. 17, Spring 1966, pp. 9-11. JSTOR.

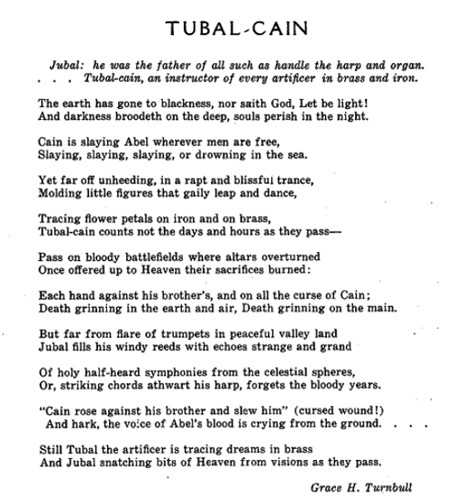

- Turnbull, Grace Hill. “Tubal-Cain.” The Art World, vol. 2, no. 4, July 1917, p. 312. JSTOR.

- “Washington, D.C.” American Art News, vol. 7, no. 20, February 27, 1909, p. 2. JSTOR.

- “Why Were These Women Judged By Men?” The Art Digest, January 15, 1932, p. 17. Google Books.

- Ziegler, Caroline L. “Creative Appreciation of Lizette Woodworth Reese.” Conducting Experiences in English: A Report of a Committee of the National Council of Teachers of English. Chicago: The National Council of Teachers of English, 1939, pp. 140-145.