Florence May Esté

Renowned in her day for oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, etchings and engravings. Florence Esté was born in Cincinnati, Ohio on May 25, 1859 (this is the date mentioned in most of her passport and registration forms, though her application for a passport in 1874, marks her date of birth as 1851 and many websites mention 1860).

Esté’s family genealogy is almost impossible to unravel since names, dates, ages, and affiliations vary from one official document to another. Accounts often attribute the Honorable Judge David Kirkpatrick Este as her father, but this does not seem to be the case. Records on Ancestry.com refer to David K. Este who died in 1864 and had 2 children with Eliza Phillips Este: Lucy Phillips Lea and Charles Este. We know her mother was Eliza Phillips Houston Este, about whom there are very few records. Oddly enough, when Esté’s mother traveled to France and Switzerland sometime around 1855, she listed that she had five children: Lucy, aged 14, Charles, aged 12, Lilian, aged 9, Florence aged 7, and Elizabeth, aged 5. The 1870 US Federal Census Bureau identifies Florence, Lilian, and Elizabeth as “inferred children,” but Esté does claim Charles, Lucy, and Elizabeth as her siblings on passport and embassy registry records (Ancestry.com).

Interestingly, there seem to be no photographs of Florence Esté; the only one we found is a badly reproduced version in one of her passport applications.

Be that as it may, Florence and her mother traveled to Paris in 1875 “for pleasure” (stated in Florence’s passport application). This could be the time she met up with her friend Emily Sartain who was studying with renowned French painter and engraver Évariste Luminais. In her last year in Paris (1926), Sartain shared a studio with Jeanne Rongier, where Esté seems to have worked (Swinth, 57). When she returned to the U.S., Esté attended the school of the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, studying under Thomas Eakins, from 1876 – 1882. She also studied with William Sartain (1882?), whose studio was intended as an alternative to Eakin’s classes – offering dissection and life classes, and drawing and painting from male and female nudes. Other students of Sartain at the time were Cecilia Beaux, Dora Brown, and Julia Foote. In 1885, Esté shared a studio with Blanche Dillaye in Philadelphia and, that same year, she and her mother both stayed in Gloucester, Massachusetts where, it seems she studied with Stephen Parrish (Schneider, 163). In the summer of 1886, she also stayed around Lake Placid, where her studio was apparently spared from being destroyed in a large nearby fire. By that time, Florence had already won recognition for the works she had exhibited.

Mother and daughter returned to France in 1887, and Florence is listed as studying at the Académie Colarossi in 1889 (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 21, 1889, p. 8), though there is no information on the duration of her stay. In her registration form for the U.S. Consular services in 1915 and 1920, Florence only remembered visiting France as a child, stating that she lived in Paris from 1898 to 1920, with “various visits” to the U.S. In both forms, she identifies her French home as 28 avenue de l’Observatoire in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, a stone's throw from the Luxembourg gardens, and the Montparnasse area:

I go out on my balcony (I am on the fourth floor) and see the long rows of blazing lights down the Boulevard [...], the grave, the old buildings of the Maternité, the many windows gleaming [...] and calm, overhead, a splendid moon" (Oakley, 583).

She was within walking distance of the American Girls' Art Club, the Holy Trinity Lodge, and numerous other art studios and academies. This is where she remained for the rest of her life. Her mother was her constant companion until she died in 1909.

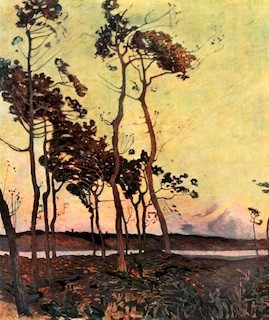

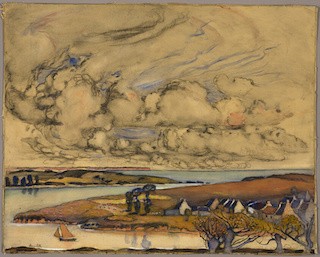

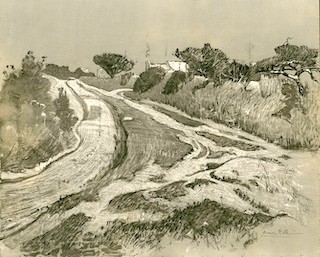

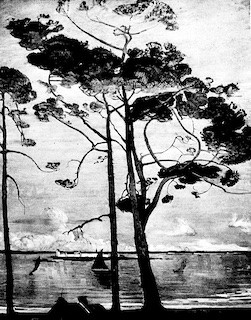

Paris notwithstanding, Brittany was Esté’s realm of predilection. She and her mother spent the summers in St. Briac, a coastal town between St. Malo and Dinard, replete with footpaths skirting Brittany’s spectacular Emerald Coast. From here, she could admire and draw the small islands, rocks, and coves, and the resplendent diversity of colors that reached their peak at dusk. In this arena, her studio was the great outdoors, which she captured in paintings that often were as imposing (some measuring 3x2.5 yards) as her love for Brittany’s “big horizons, its radiant colors, its villages, and St. Malo, rising like Venus, from the blue sea” (cited in Oakley, 583). Her browns, gold, and rose reflect the colors she witnessed. Florence often had to walk for miles along the coast in order to find the vista or scenery that kindled her imagination. In his homage to Esté, Thornton Oakley evoked her lengthy peregrinations: “[...] how vividly I can remember that summer, when I saw her for the last time at St. Briac – her sturdy figure, laden with her canvases and easel, tramping, tramping along the coast among the villages she so adored” (582).

In Saint-Briac, Esté met and worked with another figure well-known to its inhabitants – the artist Alexander Nozal, who, like her, was an ardently independent painter and lover of landscapes and who criss-crossed every corner of St. Briac and other parts of France by foot or bicycle. St. Briac is also where Esté’s mother died in September 1909, leaving a veritable void in her daughter’s life: “She has been dead for eleven years, and I never see a beautiful thing or read a noble verse without thinking of her radiant presence” (cited in Oakley, 584). Documents in Ancestry.com show that her mother was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Pennsylvania on October 4, 1909.

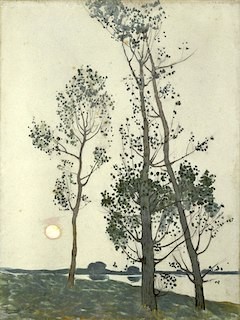

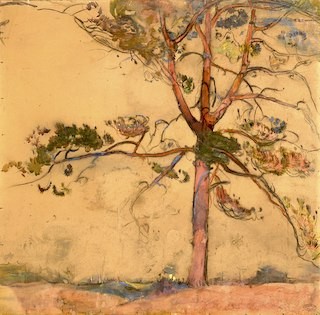

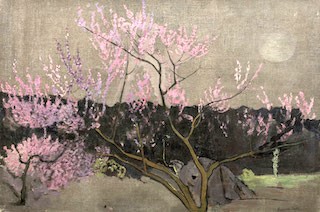

For many French art critics, Esté “Japanized” Brittany, since they perceived in her work a resemblance in style and idiom with Japanese prints. However one wishes to categorize her art, one is struck by her infinitely affectionate, almost reverential gaze:

[...] whatever technique she employs, whether she paints in oil, pastel or watercolor, whether she composes an easel painting or a decorative panel, she is much less concerned with fixing the transient modalities of immediate, direct reality, than with highlighting its permanent characteristics, its enduring expressions, its profound and eternal poetry. [...] to move us and awaken in us memories of the impressions and sensations we ourselves have felt in the presence of the same spectacles as those that have moved [her] or to suggest to our eyes, so clearly and so strongly, the reality that, having never yet seen them, we take possession of them through the interpretation [she] imposes on us, as if they were a true and tangible fact! (translated from French, Mourey, 34, 36).

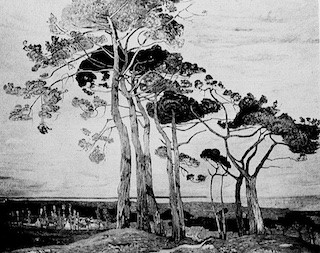

Her symbiotic relationship with nature, and with trees in particular, is not only evident in her art but also in her letters. During WWI, in the summer of 1915 the entire town of Saint-Briac had to be evacuated because enemy troops had made inroads in the area. Esté returned to Paris for a time. When she resumed her summer retreats, she found a rather desolate landscape. A letter she wrote to Thornton Oakley describes the pain she felt upon seeing that all the trees in the area had been radically unearthed:

Your Pine Tree (I had one last year I called Thornton Oakley's) was to have been my first work this summer. It stood on the edge of a forest five miles from here. When I arrived there in June my heart stopped beating. Your tree – and every tree I have painted for years, big, noble splendid creatures, centuries old, had all been hewn down. Not one left. 'Requisitionnés' by the Government and all sent to the Front. It was a most tragic moment. My dear friend's leaving this world [unclear about whom she is speaking] produces the effect that came to me when I saw all my splendid pine trees cut lying dead on the ground. It will not be given to man in Brittany to see their like again. My trees having been hewn down, I have turned to small villages and to rapid and big water color studies of the sea (Oakley, 582).

Although Florence Esté permanently relocated to France, staying even during WWI when the great majority of American artists left the country, she never lost sight of her compatriots or her country of origin, expressing her chagrin at being cast so far from away from her own shores:

I am – passionately – of my own country and long to have a small place there among my fellow workers. Oh dear! to live out of one's own country is not all joy. I have a delightful existence – brimful of pleasant things and notable people. But no notable people can replace the soul of one's countrymen. I, who have been forced to live abroad, have never approved of living out of one's own country. [...] But I miss one thing I have always longed for – my own country and my own countrymen. [...] I have left the “Glorious Top of the Hill” and the path downward, though still delightful, makes me realize what I have missed in living away from my own country and from all of you." (Oakley, 584).

Interestingly, in her passport application as in her registration with the U.S. consular services, she always refers to her stay in France as temporary; In 1918, she applied for a passport in Dinard, France within which she asserts: “I came abroad in July 1915 for the purpose of studying painting. I am still continuing the study of painting, but at the conclusion of the war, I shall discontinue such study and return to the United States for the purpose of residing and performing the duties of citizenship therein.” Nothing has yet surfaced on her actual travels, but it seems she only returned twice to the U.S.: in 1909 after her mother’s death; and for a few months in 1912.

All the same, throughout her French residency, Esté was active in artistic circles of the American Colony in Paris and invited visiting American artists to her apartment or home in Brittany. At different periods of time, her close friends seem to have been Cecelia Beaux, Lucy Scarborough Conant, Elizabeth Nourse, and Emily Sartain. Of the friendship between Beaux, Conant, and Esté, Geneva Armstrong, wrote the following in her privately printed book, Woman in Art (c. 1900):

Some years ago a group of young women were students together in Paris. A sincere attachment grew into a lasting friendship, though distance and circumstances kept them mostly apart. But they had the experiences and memories of delightful days together, all of which enriched and sweetened life. The three friends might be treated here as merely three art students, but the rarity of such a tie as theirs seems like an oasis in the impersonal, tumultuous imperatives of the NOW. Lucy Scarborough Conant was one of the group. [...] Her two friends were Cecilia Beaux and Florence Este. A vital, vivid trio (140).

Esté also worked with other American expatriate painters, like landscape painter Charles Augustus C. Lasar, whom she admired. Considered as the dean of the American artist colony in Paris, his studio in Montparnasse attracted innumerable students. Besides painters, especially American, Esté felt that other people didn’t “count” (cited in Oakley 583). In fact, she generally shied away from the social limelight. Her letters to artist Thornton Oakley speak of a rather solitary existence; even when she was in Paris or in the company of others, she did not engage much with the trappings of the social scene: “Last winter I gave five 'big' (for my rooms!) receptions. Everybody came. Everybody enjoyed themselves and each other. I, alone, saw no one, enjoyed nothing, and no one even noticed they could not see me because I was always smiling and shaking hands" (Oakley, 583-584). An air of melancholy surrounded her existence: “[...] I have a heart which is talented beyond measure for (useless) suffering. It is quite restored now – only two or three cracks left” (cited in the American Magazine of Art, 1926, vol. 17, no. 6, p. 307).

Art was her anchor and safe place, as was the quiet contemplation of nature, reading, and epistolary interactions. She was not a prolific painter, but gained significant notoriety for her work, both in the U.S. and France. Nonetheless, she tired of the struggle to make ends meet through her art, despite the honors and prizes she received throughout her life:

Well, Painting is a Glorious Misery. It's like rushing up a hill to see the sun rise. One gets to the top with toil and much blown . . . but the sun most generally rises for us in a glum cloud. All the same, we who have embarked in the derisive trade where the laborer so rarely seems to get much hire—we, all the same, are 'les fils du soleil' (Oakley, 585).

Despite her seeming discontent with the hardships of her chosen path, Esté regularly presented her work in important exhibits.

By 1894 she was exhibiting in the French Salons, where she was represented either at the Salon de la Société nationales des Beaux-Arts or the Salon des artistes français on the following dates (at least): 1894, 1895, 1896, 1901 (when she was elected a membre associé of the Salon des artistes français), 1902, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1909, 1910, 1911 (on the jury of the Salon des artistes), 1912 (named sociétaire of the Salon nationale des beaux-arts), 1913, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1924, 1925, 1926 (right after she died). She also exhibited her work in numerous French galleries, notably, Georges Petit, Goupil, Knoedler, and Chaine et Simonson. She was a member of the "Les Quelques," an association of 25 women artists, both French and American. Her work was lauded by French critics and received much media attention. Writing about the Salon de la Société des Beaux Art in 1900, the renowned journalist and art commentator noted “... hers is a name to remember” (cited in The Times, January 5, p. 9). Several of her paintings were bought by private collectors as well as the French government (e.g. “A Far Horizon,” Luxembourg Museum).

Esté was also regularly represented in U.S. exhibitions, mainly on the east coast, in Philadelphia (at the Academy of Fine Arts beginning in 1900), but also in New York City (Armory Show of 1913), Buffalo, Boston, and Chicago (Art Institute). The American press kept abreast of her shows in the U.S., England (where she sold all the work she exhibited in 1905), and France, and especially lauded every success she had in the French Salons. In 1905, she painted a decorative panel that was placed over the stage of the lecture room of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, which was shown at that year’s Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts under the title of “Brittany Pine Trees.” She was made an honorary member of the Philadelphia Watercolor Club (c. 1902-1921), which included several of her works in its exhibitions. In 1922, reproductions of her work were shownat an exhibit in the entrance hall to the Academy of Fine Arts, which honored Philadelphia's four most famous women artists: Mary Cassatt, Cecilia Beaux, Violet Oakley, and Esté (Powell, 10).

In addition to painting, she also translated French articles for Eliakim Littell’s The Living Age, a weekly literary magazine (1844-1941).

In Paris, she also participated in the numerous exhibitions staged by American art associations.

As early as 1895, she exhibited in the American Women’s Art Association show at the Girls’ Art Club, situated around the corner from the Académie Colarossi. The annual exhibitions attracted not only the who’s who of the American colony, but also the gatekeepers of the French artistic community. They thus served as a powerful springboard for potential buyers and other exhibits. After a seeming six-year hiatus, Florence participated in the following AWAA exhibits:

- 1901: “Les Ajoncs” and “Les disparus”

- 1903: a snowy landscape, a mountain

- 1905: blossoming peach tree and another painting; she was a member of the jury together with Elizabeth Nourse and others

- 1906: three color drawings of Brittany; she was a member of the jury

- 1907: she was that year’s President of the Association but did not show any works due to illness.

- 1912: loan exhibition that gathered numerous American artists, and where only three women were represented: Florence Esté, Elizabeth Nourse, and Janet Scudder

- 1914: the AWAA’s final exhibition

In 1906 a competing art association, the Art League for Women, was formed as part of the Church of the Holy Trinity’s Lodge. Located in the Latin Quarter, in a Carmelite convent on rue du Val de Grace, not far from her apartment and the Girls’ Art Club, the Lodge hosted the League’s regular exhibitions. The first president was Elizabeth Nourse, and Florence Esté presided from 1908-1913, when the League was disbanded due to lack of funds at the Lodge. During its existence, it served as a great resource for women artists since it staged annual exhibitions that lasted two weeks and attracted as many as 500 visitors, often opened under the auspices of the American Embassy.

Esté also became a member of the International Art Union created in 1909 by socialite and philanthropist Grace Whitney Hoff, who had also founded the Student Hostel in 1906 for Anglo-American women – a kind of rival organization to the Girls’ Art Club. As honorary President of the Union, Whitney Hoff, staged several art exhibitions and established the Whitney Hoff Museum Purchase Fund to be used to buy the best artwork and donate it to an American Museum. It seems that the Union was short lived and only staged exhibitions from 1909 to 1914. With respect to Esté, two are worth mentioning:

- 1913 – Mary Cassat was the honorary president. Held in the spring at a gallery on Faubourg St. Honoré, the exhibit caused quite a stir because the jury had awarded the 1,000 franc prize to a portrait by Anne Goldwaite. Hoff decided that the portrait was too small to be worth the prize, and attributed it to Florence Esté, for her landscape of trees in Brittany. According to the New York Times, Esté had refused the prize (July 20, 1913, p. 22).

- 1914 – Florence Esté formed part of the hanging committee and showed in the exhibition at the Hessele Gallery, the last of the Union’s exhibits.

Florence Esté died suddenly in her apartment at 28 avenue de l’Observatoire on Sunday, April 25, 1926. She had just returned from a service at the American Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity. A note found in her apartment stipulated that we wished to be buried in St. Briac. The Philadelphia Water Color Club, devoted a memorial room to her work in its 1926 annual exhibition. The year following her death, several of her friends and admirers organized a retrospective exhibit at the Galerie Charpentier, featuring 73 watercolors, under the patronage of Myron T. Herrick, U.S. Ambassador to France.

In his homage to his friend, Thornton Oakley writes:

Her death leaves a void in the world of art impossible to fill. From those who knew her well her death takes likewise an inspiring personality. Yet she had, I know, comparatively few close friends. The lives of these few she enriched by sharing with them her buoyant spirit. Hers was a life of struggle. Fate to her, in many ways, was cruel. It swept away her fortune; it swept away the greater number of her nearest and dearest comrades; it cast her, stranded, upon a foreign shore, there held her prisoner. But her courage never quailed. Dauntlessly she faced the years, and by her ardor, will, her love of nature and of life, she rose to take her place among the master-painters of the world (582).