American Hospital No. 3, 1917 – 1919

Elisabeth Mills Reid was internationally renowned for her philanthropic support of medical causes (hospitals, nursing education, public health drives) and had been a lifelong patron of the Red Cross. When the Americans entered WWI, she felt it was her duty to support the war effort.

In 1917, 4 rue de Chevreuse transitioned from a French auxiliary hospital into a military hospital for the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) in collaboration with the American Red Cross (A.R.C.). On April 17, 1919, six months after the armistice, the military completely withdrew from 4 rue de Chevreuse. All army supplies were removed and Reid's furnishings were returned to the empty rooms.

The Transition

In a September 27, 1917 letter to General John J. Pershing, Reid announced: “I have heard from the Ambassador in Paris that my Hospital in the rue de Chevreuse has been given back to me, so I hope soon to have the great pleasure of handing it over to you for the use of your officers.”

Prior to her official correspondence with Pershing, Reid had already been in contact with Col. Alfred Eugene Bradley, head of the medical corps of the A.E.F., concerning the possibility of transferring the hospital from the French Red Cross to the A.E.F. His response on August 19, 1917 indicated the Americans’ desire for a clean break with the French and total control over the hospital:

It is understood that you will sever any claims the French may have in any way over the Hospital […] Arrangements can, of course, be made so that Mrs. Shields can remain in her present position undisturbed, but it must be understood that all connections or relations of the French must be entirely broken off.

Reid confirmed that indeed “everything has been done to get a clear title, without creating any antagonism either with the French government or the French Red Cross” (letter to Pershing, September 27, 1917). On September 28, she briefed Bradley on her plans:

I am delighted to be able to tell you that the French have yielded me my Hospital in the rue de Chevreuse, and that I hope to be able to hand it over to General Pershing for the use of American military officers about November 1. The French are leaving the Hospital on October 15th […]

Red Cross officials were very disappointed to lose the hospital (Lambert, October 11, 1917) but after a good deal of haggling between Reid, A.E.F. officials, and the A.R.C., it was decided that Red Cross personnel could also use the site as long as priority was always given to wounded soldiers. In his October 23 memorandum to A.E.F. Surgeons and Lines of Communication, Bradley, who had now earned the rank of Brigadier General, clarified the responsibilities of both entities at 4 rue de Chevreuse:

On November 6, 1917, Pershing posted General Orders (no. 54), informing the A.E.F. of the transition:

The hospital at 4 rue de Chevreuse, heretofore known as 'L'Hopital Auxiliaire No. 53' will be taken over by the American military authorities about November 15, 1917, to be administered and conducted in connection with the American Red Cross. It will be known as American Hospital No. 3 and will be in control of the Commanding General, line of Communications, American Expeditionary Forces.

Upgrades

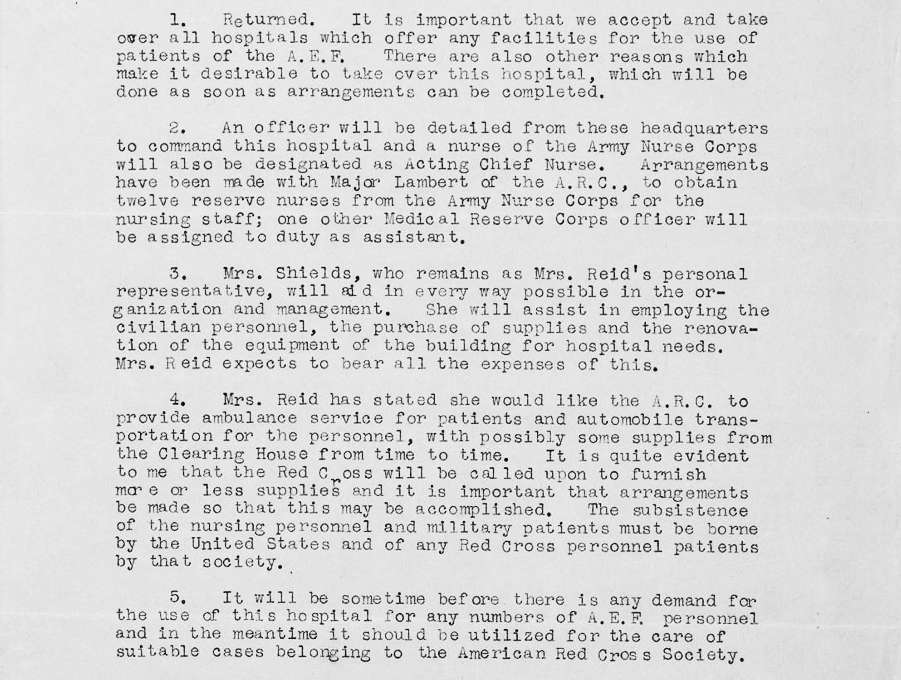

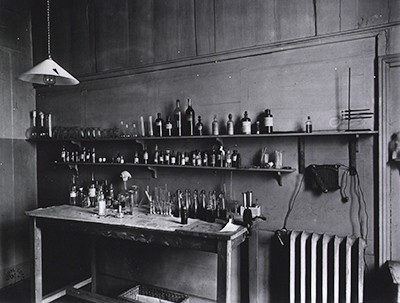

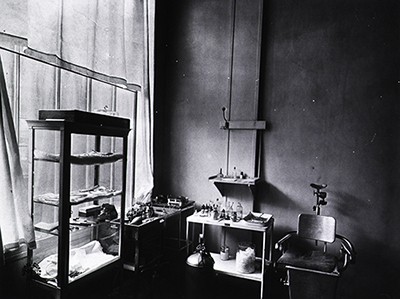

Further renovations were undertaken when the American Red Cross and the A.E.F. moved to the hospital in 1917. Reid insisted on covering the costs not only to transform and equip the site, but also to provide other supplies to care for the wounded and make the officers feel at home so far away from their own. She also leased several apartments in the neighborhood for orderlies on rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs (#56, #86) and studios on rue de la Grande Chaumière (#8) in which to store her furniture from the Girls' Art Club.

On September 28, 1917, she briefed Bradley:

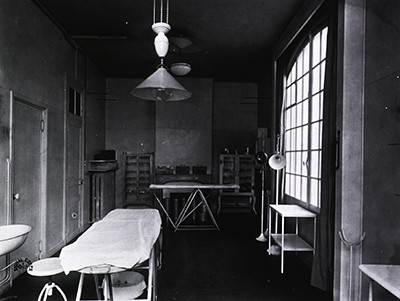

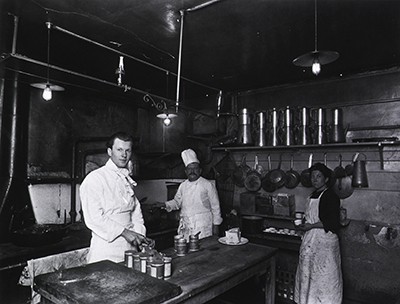

I want it to be thoroughly cleaned and the kitchens painted, which will take about a fortnight. […] I am having a lift put in, and shall add a good X-ray plant, and, of course, the Hospital will be fully equipped as to beds, furniture, and everything of that kind.

The Congressional Record of September 24 described the accommodations at 4 rue de Chevreuse:

The hospital was opened and received its first patient on the 12th of December, 1917. At this time there were accommodation for 50 patients in single and double rooms. It was beautifully and artistically, even luxuriously, furnished, has ample recreation facilities, a large, well-equipped library and reading room, which is kept well supplied with American, English, and French magazines, periodicals, and daily papers. In addition, there is a large reception room containing a Steinway concert grand piano, and a lounge room provided with games, card tables, pianola, and victrola. Every effort has been made and no expense has been spared to equip all parts of the building comfortably and in a homelike manner (1704).

Carolyn Wilson of the Chicago Tribune provided even more information about the facilities:

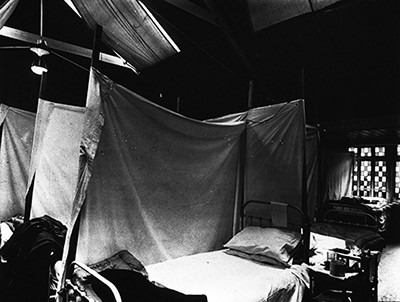

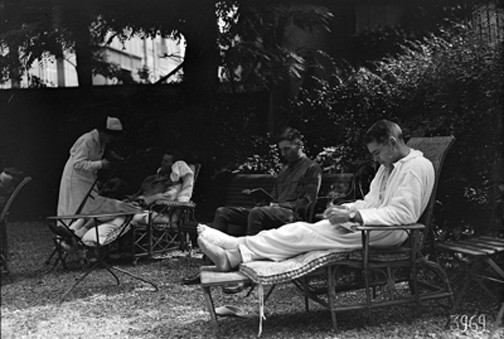

[...] all the old studios have three beds in them now, and the little Episcopalian Church in the yard has been turned into a big ward, and two extra barracks put up in the yard too, so that it can accommodate 300 officers (...) then on top of the annex is a big roof garden terrace, where the more hardy may sun themselves out of their hospital pallor (6).

Grace Hill Turnbull, an artist who had resided at the Club in 1914, returned in 1918 as a Red Cross volunteer. She recalled this visit in her autobiography, Chips From My Chisel:

I went yesterday to our dear old American Arts Students Club to learn how it was being used. There, as everywhere, khaki men were swarming; a khaki man in the concierge's lodge, khaki men on beds in the garden where we used to have breakfast; in the ballroom where we had our fancy-dress balls; in the chapel; in my studio where I used to paint the mothers and babies! The ballroom had suffered the greatest transformation - the tapestries had been covered with cheesecloth and the white beds were packed like sardines, not in rows with alleys, but as close as could be in all directions; many of them had wooden frames attached so the poor wounded limbs could be drawn up as required (69).

Reid, who was in regular contact with Red Cross officials, was dedicated to ensuring that the property suited the needs of all officers, soldiers, and hospital staff. She visited the hospital whenever she could and regularly inquired about the day-to-day operations, medical care, and the general atmosphere. An excerpt from her January 14, 1918 letter to Major Lambert demonstrates her willingness to make changes as needed:

I am so anxious to know what you think of my hospital now that it is running. I am constantly wondering whether you find everything you want there and if it is all satisfactory. It would be doing me a great favour if you could make any suggestions as to its improvement in any way - if there are little additions that could be made in its arrangements or equipment that would make it more convenient or increase its usefulness. Now that there is really a need for it, and that it is filled with our own people, I am very anxious that nothing should be left undone that could add to in any way to the comfort of the patients and the staff.

Personnel

In early November, Captain Walter W. Manton, a Harvard graduate (class of 1911) and an officer of the Medical Reserve Corps, was named the Commanding Officer of the hospital. He was assisted by Chief Nurse Eleanor R. White, a reserve nurse in the Army Nurse Corps; her assistant was Agnes F. James, also in the Army Nurse Corps, who served as the Chief Nurse at another hospital in Paris.

The first American patients were admitted on December 12, 1917. At that time, there was space for 50 wounded soldiers in single and double rooms (Congressional Record 1704). Manton worked with Reid to organize and equip the hospital. Correspondence between Reid and various officials suggests that there were regular personnel issues, missed deliveries of supplies, and other logistical hiccups. Upon completion of his duty at the hospital in early 1918, Manton was assigned at his own request as Captain to the 26th Infantry, 1st Division, A. E. F. He was wounded near Soissons, and received the Distinguished Service Cross "for extraordinary heroism in action near Soissons, France, July 18, 1918” (Harvard Alumni Bulletin 658). Ironically, he returned to rue de Chevreuse as a patient; in a letter to the Journal of the Michigan State Medical Society dated July 21, 1918, he wrote:

Here I am back again at the little hospital. It is crammed. We've lost almost 90 per cent, of our regiment. Most all my friends are killed or wounded; but it was a magnificent attack. Have small wound in right forearm, so am trying to write with left hand. Everything bully (414).

Manton was replaced in January 1918 by Major Warren L. Babcock (who later became Lieutenant Colonel), superintendent of Grace Hospital in Detroit, Michigan (Congressional Record 1704). He carried out the plans formulated by Reid and Manton, completing the hospital alterations and construction work. He also gradually expanded the staff. On average, about 30 patients were admitted daily.

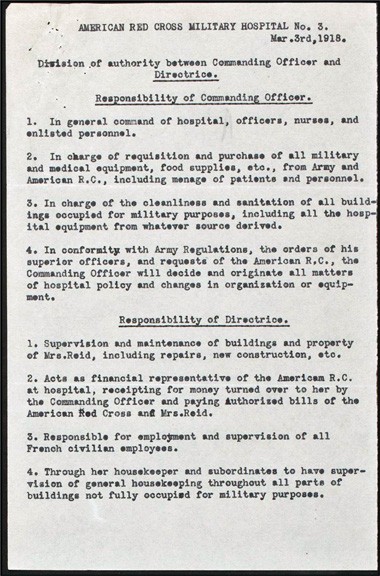

Under his command, the respective responsibilities of the Commanding Officer and the “Directrice” (Roselle Van Allen Shields) were finally clearly outlined (March 3, 1918):

In April 1918, Major Samuel Lloyd (later Lieutenant Colonel), "was ordered to relieve Major Babcock" (Congressional Record 1704). Lloyd, who had been working since February as Chief of the Surgical Service, assumed command of the hospital. On July 27, 1918, eight of the twenty nurses detached from a Naval Base Hospital at Brest were sent to 4 rue de Chevreuse. The situation they encountered is poignantly described by Mary Caldwell in a passage from Dock’s History of American Red Cross Nursing:

At seven A.M. the following morning we were detailed to different wards and encountered a very decided change of work. Here we had patients from generals down to lieutenants, the cases nearly all surgical, the officers mostly suffering from explosive wounds and compound fractures. No more great black stevedores, with mumps and measles! The majority of our patients belonged to the 181st, 2nd and 77th divisions. Many of them were prominent Americans. Some of our beloved Marines from the S.S. Henderson, whom a year before we had last seen marching away from the ship well and happy, came back to us shattered and miserable, to be nursed back to a poor resemblance of their former sturdy selves (748).

Relations between Major Lloyd and Elisabeth Mills Reid were poor. In all of her letters to Lloyd's superiors, she expressed her displeasure with conditions at the hospital. Reid characterized Lloyd as a bad housekeeper and executive officer whose skills as a surgeon were also subpar. She proposed to General W. Ireland, Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, that Lloyd be replaced (August 27, 1918 letter) but her request was denied:

I sincerely trust it will not be necessary to change the Commanding officer at no. 3 again. There is nothing that demoralizes an institution more than the constant changing of the Commanding Officer. Colonel Lloyd may not be everything that may be desired but he has made a very good Commanding Officer and is an excellent surgeon. However, to make sure on this point, I will consult with Colonel Murphy and the officials of the American Red Cross when I am in Paris next week and will determine on this necessity. I sincerely trust, however, it will not be necessary to make a change (Ireland, August 31, 1918).

Reid swiftly wrote to Murphy of the A.R.C, calling Lloyd a "drifter" incapable of keeping the premises clean, or of managing the kitchen staff, which she also wanted to change (September 10, 1918). Lloyd, to whom Reid’s complaints were made known, wrote a terse memorandum on December 15, 1918 to the A.R.C Section of Hospital Administration categorically denouncing “complaints from America” as undermining the smooth functioning of his hospital:

The Commanding Officer seriously objects to complaints with regard to the management of this hospital, based on insufficient and inaccurate information, from anonymous sources. Never in the history of this hospital have all departments been running so efficiently, and so effectively as they are at present.

Despite Reid’s insistence, Lloyd remained in command until the army withdrew from rue de Chevreuse in 1919. Military records show that he was highly regarded and supported:

Since he has commanded No. 3 the hospital has tripled in capacity, and this has been done without overcrowding or relaxing the effort to make the hospital not only a place of care for the wounded officers but to provide a homelike and happy atmosphere. Mrs. Reid has spared neither time nor money to bring this about, and in this she has been ably seconded by the commanding officer and his whole staff of medical officers, nurses, and corps men (Congressional Record 1704).

Patients

In the last six months of 1918, “1524 patients were admitted to Hospital no. 3 [...]; of those 27 died. They totaled 31,491 hospital days” (Dock 612). 23 nurses and 20 orderlies cared for the soldiers, while an average of seven officers oversaw the various wards and services. Among the many patients who convalesced at this hospital was Captain Archie Roosevelt, son of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had been severely injured in 1917 and was soon discharged from the army with full disability.

Reid’s unhappiness notwithstanding, the hospital received only favorable reviews for its effectiveness and atmosphere under Lloyd’s command. Reverend Edward Newell Ware, who had sailed for France in 1918 as a chaplain in the service of the American Red Cross, was first assigned to work at Base Hospital 13 in Limoges, then at Military Hospital No. 3 in Paris. He described his experiences at 4 rue de Chevreuse:

In March I was assigned to duty in Paris with the Red Cross Military Hospital N° 3 and N° 112, both hospitals caring for officers only. N° 3 was organized and equipped and mothered by Mrs. Whitelaw Reid, of New York. No other hospital in all of France or in any other country, our own America not excepted, could compare with N° 3 in comfort afforded its patients. Here more generals were cared for than in all our hospitals combined. To be assigned to this service during my last days in France was to me a signal honor, conferred upon me by the Red Cross (8).

In the "Special Notes" of his comprehensive 1919 report on medical facilities and surgical equipment on the Western Front and in England during WWI, William Seaman Bainbridge praised Hospital no. 3:

The hospital is so beautifully arranged and equipped that it is a model of comfort and convenience. Mrs. Whitelaw Reid has taken one of the arts' students centers at the edge of the Latin Quarters and fitted it up as a hospital for American officers. There are already 75 beds, and plans have been made to enlarge the capacity. Nothing reasonable is lacking that money can buy which would add to the comfort or aid in convalescence. The open court with its trees and flowers and the location on a quiet side street off the boulevard afford surroundings that are most attractive and restful (126).

Other accounts of life at the hospital and on the severity of patients' wounds can be found in newspapers, both English and French. Carolyn Wilson, Special Correspondent to The Chicago Tribune, praised the hospital facilities and chronicled the travails of its convalescing officers in an article published on September 23, 1918:

It is a lovely spot to convalesce in [...] built around a big inside garden, where flowers are bright and gay and the trees make grateful shade as the men lie out in their comfortable hammock chairs [...]There are quite a few shell shock cases here, this trouble being more prevalent among officers than men. An officer I was visiting told me of a captain named Gill, who had lost his memory and who was lying next him in a chair in the garden, and was always singing that old song, 'When Love Was Young.' 'I've heard it somewhere. I know it from somewhere,' he said to his friend's questioning. Quite at hazard, knowing nothing of his past, the friend asked, 'Ever see Brown of Harvard'? And quick as a flash the answer came back, 'I played with Woodruff in 'Brown of Harvard,' and for five minutes stage reminiscences poured forth, and Captain Gill had that much more memory of his past life to the good (6).