Marguerite T. Zorach, 1887 – 1968

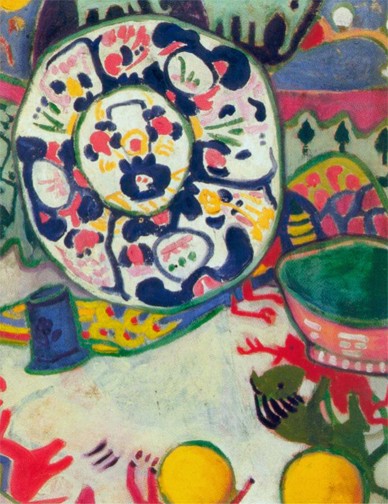

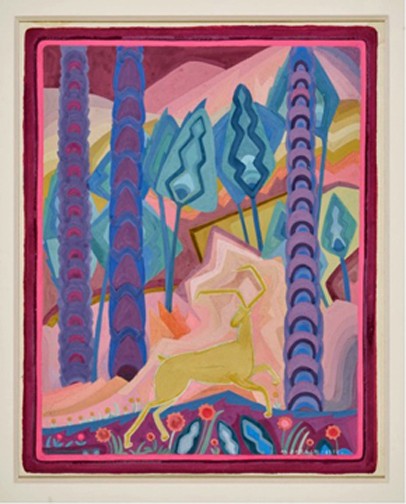

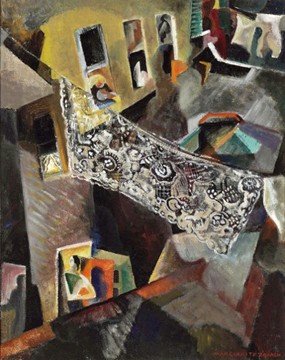

Born in Santa Rosa, California on September 25, 1887, famed Modernist artist Marguerite Thompson Zorach was the eldest daughter of wealthy lawyer William P. Thompson and his wife, Winifred Harris. While much of Marguerite’s prestige has been overshadowed by that of her husband, sculptor William Zorach, she earned critical acclaim in the 1910s and 1920s, and is recognized as a significant American Fauvist painter, graphic designer, and textile artist. According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which owns the largest collection of her works, "She was an early exponent of modernism in America, employing the bold colors of the Fauves [...] with the striking, and controversial, forms of cubism." Her work is held by several American museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Newark Museum, Portland Museum of Art, and Whitney Museum of American Art.

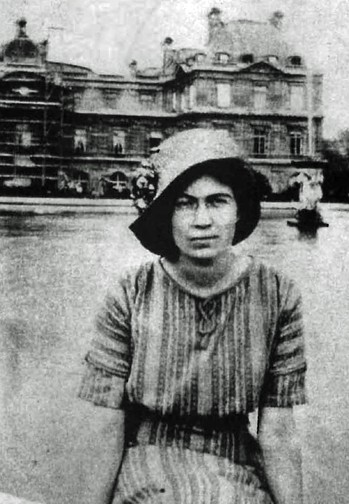

Her artistic skills became evident to the Thompson family when she was just a child, but she also excelled academically and was admitted to Stanford University in 1908. She only stayed a short while, opting to forego a degree and travel to Europe to join her aunt, Harriet Adelaide Harris, in 1909. A teacher, amateur painter, and friend of Gertrude Stein's, "Aunt Addie" had been living in Paris since 1900. She admired her niece's creativity and wanted her to experience the vibrant avant-garde art world in France. Harris even paid for her passage and used her social connections to introduce Marguerite to important schools and artists (Picasso, Zadkine, Rousseau, Matisse). The next four years in Paris were groundbreaking for her artistic evolution.

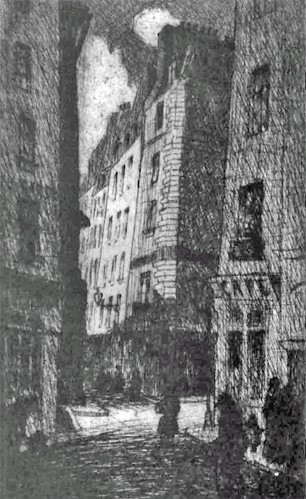

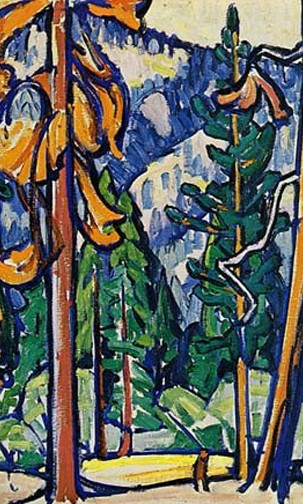

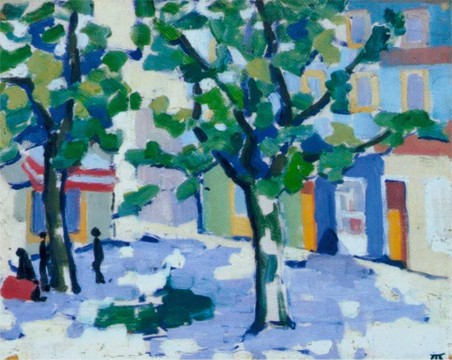

Upon arriving in Paris, young Marguerite went straight to the Salon d'Automne, where the colorful canvases of Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice Vlaminck were highlights among the two thousand works on view. While many visitors to the Salon found these so-called Fauves shocking, this budding twenty-one-year-old artist "[...] gloried in what she saw. Something new was in the air [...] These paintings, particularly Matisse's, stirred her independent nature and questioning mind" (Kennedy 95). At the Salon, she also saw the paintings of John Duncan Fergusson, with whom she would soon collaborate (Colleary 24). Like so many others, Thompson Zorach listed her Paris address as 4, rue de Chevreuse.

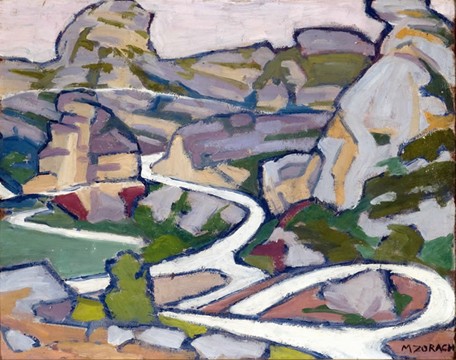

Despite her aunt's wishes, Marguerite was not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux Arts and did not remain a student at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, which she felt was too conservative. She opted instead to attend the post-Impressionist Académie de la Palette, headed by Jacques-Emile Blanche from 1902 – 1911, where she worked with Scottish colorist John Duncan Fergusson, a sociétaire of the Salon d'Automne. Fergusson was also the artistic director of the periodical Rhythm, which was active from 1911 – 1913 and which promoted innovations in art, music, literature, and critical theory in its 14 issues. Rhythm included drawings by Thompson in 1911 and 1912. At the Académie de la Palette, she also befriended artists Anne Estelle Rice (who had a romantic and professional relationship with Fergusson) and Jessica Stewart Dismorr, with whom she shared a studio. Marguerite and Jessica visited museums and galleries throughout Europe and spent the summer of 1910 together in Provence. Dismorr became one of Britain's foremost women "[…] engaged in progressive art, literature and politics […] who, despite suffering from mental illness, was a pioneer in four modernist movements: rhythm, vorticism, postwar modernist figuration and abstraction" (Ashby).

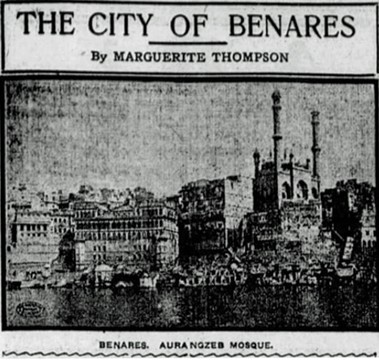

Traveling in Europe was thrilling for Marguerite, and she often wrote articles chronicling her experiences for her hometown newspaper, the Fresno Morning Republican. In one article dated December 20, 1908, she described the Latin Quarter in Paris as "the Spot in All the World Where Genius Most Do Congregate and Where the Democracy of Achievement Has Freest Reign" (Burk 2008, 89).

A prevailing belief in this period was that young American women should not explore Paris without the safety and guidance of a chaperone, but Marguerite was quick to dispel this notion, describing the nonchalance and freedom with which one could venture to an "evening musical at the Girls' Club in company with one or two other girls" (Burk 2008, 89). She also playfully poked fun at the supposedly scandalized Parisians who observed artists from the Girls' Club sketching on the city streets or in the countryside:

I remember reading not long ago in a San Francisco paper how the girls of this [...] American Girls' Art Club had astonished all Paris by taking long tramps and sketching expeditions into the woods of France unchaperoned. Astonished all Paris! Why Paris never even raises an eyebrow when we bold artists brave the dangers of her forests and suburbs all alone. As is a favorite custom of girls here, I have even sketched down along the Seine among the roughest class of workmen and tramps and was never more courteously treated anywhere (Burk 2008, 89-90).

In Paris, Marguerite met American artist Anne Goldthwaite, with whom she explored the bohemian expatriate circle around Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso. Along with Anne Estelle Rice and many others, Thompson showed her work at the 1910 annual exhibition of the American Woman's Art Association, whose president that year was Goldthwaite. Her etching “Giselle” was shown at the 1910 Salon des artistes français, very near a miniature portrait of Thompson by fellow Club artist Anna M. Watson. Another Fresno native and Girls’ Art Club resident, Maren Froelich, also exhibited her work at the 1910 AWAA show at 4 rue de Chevreuse and at the Salon des artistes français. The Fresno Morning Republican published a proud article on August 7, 1910 chronicling Thompson and Froelich’s achievements in Paris (3). In 1911, she exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and at the Salon des Indépendants, where she had 6 pieces.

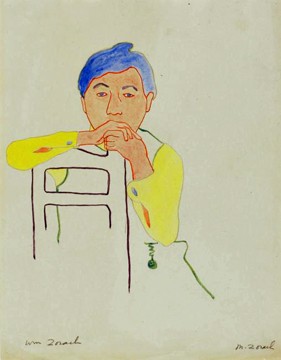

In March 1911, while studying at La Palette, she met William Finkelstein, born Zorach Gorfinkel. The two immediately formed a close relationship.

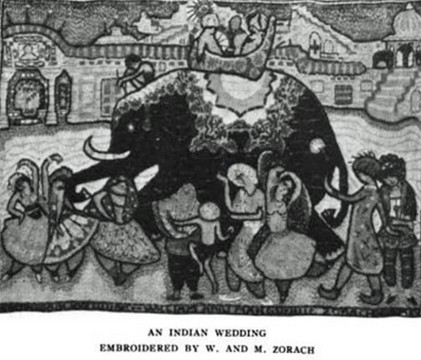

Marguerite and her aunt left Paris in October 1911 and embarked on a world tour. They visited Jerusalem, Egypt, India, Burma, China, Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, and Hawaii, before sailing back to California in 1912. The trip, which her family had hoped would break up Marguerite and William, lasted seven months and "[...] exposed her to new cultures, geographies, and styles of art, which affected her artwork profoundly" (Kennedy 96). She drew and painted throughout her world travels and, in spite of her aunt's efforts, she regularly corresponded with her beloved William. She also sent the Fresno Morning Republican articles that chronicled her adventures.

Thompson landed in San Francisco in April 1912 with immediate plans to exhibit her work. She was interviewed in The Fresno Morning Republican and commented: “‘You know, it is remarkable how many California girls are making their mark in art in Paris […] There are at least 200 young women from the Golden State studying, and many of them have accomplished creditable work” (April 25, 1912, 1). She also reported having met up with her friend and fellow Girls’ Club artist, Los Angeles native Minnie Dunlap [Mary Stewart Dunlap], in China.

By October 1912, Thompson was exhibiting in Los Angeles; her faithful Fresno Morning Republican documented the impact of her post-Impressionist work on American viewers: “Miss Marguerite Thompson is the brave painter who has returned to her native state with the dernier cri in the art world” (October 20, 1912, 7). Just one week later, on October 27, they ran another article entitled, “Marguerite Thompson, Futurist: Her Work Is Winning Attention.” While she was not a futurist in the conventional art historical sense, since she did not focus on such themes as speed, technology, or violence, she certainly was ahead of her time artistically. When asked how she became interested in post-Impressionism, Thompson answered: “‘Through my love for the decorative and my desire to study color’” (22). She also explained why her paintings usually had white frames:

Since pictures such as mine are so different from the pictures people are used to framing, it isn’t really strange that they should require different treatment. White not being a color (as is gold) forms the best frames for pictures high in key and in pure color, as it does not destroy the balance of color in the picture and brings out each color in its fuller intensity. Black is next best, I think.

In late 1912, Marguerite left California to join William in New York City. Despite her family's opposition to their union, the young couple eventually married on December 24, 1912, and both assumed William's given name "Zorach" as their surname (Kennedy 96). Their engagement was announced on December 1, 1912 in The Fresno Morning Republican (7). The announcement described William as originally from Cleveland, Ohio but obscured his Lithuanian origins. It also noted that the couple would reside in New York following their wedding.

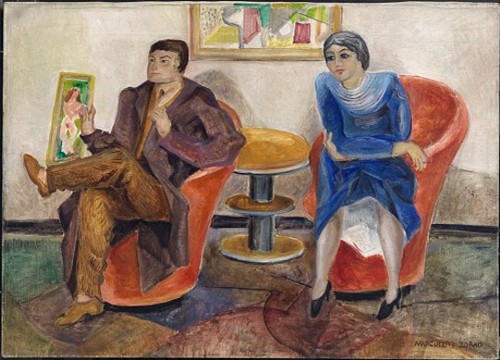

By 1913, Marguerite and William Zorach, along with Anne Goldthwaite and a host of other Montparnasse affiliates, were living in New York. They all exhibited their work at the legendary Armory Show, helping usher in modernism on a grand scale to a stunned American audience:

Although some members of the public misunderstood and even ridiculed her work, Marguerite seemed unaffected. She was brave and clear about who she was and what she believed. She also had William's full support, and they continued to paint in the same studio, helping each other with canvases, with ideas, with promoting their paintings. Although they struggled financially, these were rich, exciting years, and their collaboration nurtured them both. They exhibited paintings in their studio as well as at galleries, and they were at the center of the avant-garde community of American artists in New York (Kennedy 97).

The Zorachs lived for about 20 years at 123 West 10th Street in Greenwich Village but spent summers in New England (Burk 2004, 12). Their New York home became a kind of bohemian salon where artists and writers communed (Burk 2004, 13). From 1915 – 1918, the Zorachs summered in Cape Cod, teaching art classes for the Modern Art School in Provincetown. In 1917, Marguerite taught embroidery and design alongside fellow Girls’ Art Club alumna, Ethel Mars, who taught wood block cutting and printing (International Studio 11).

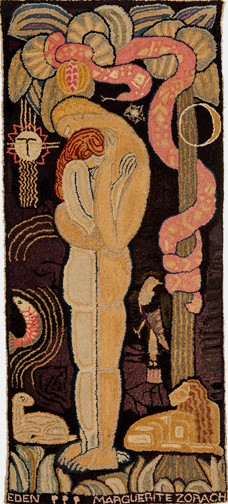

Often exhibiting jointly at galleries all over New York, the Zorachs were inseparable. One show, at the Daniel Gallery in March 1918, was reviewed for The Evening World by W.G. Bowdoin. He raved about a number of William’s watercolors but described Marguerite’s “New Hampshire Family” as “[…] perhaps intended to excite a laugh. It does that at all events in its flat treatment” (10). Bowdoin did compliment Marguerite’s hooked rug “Eden” as “highly decorative” but his review clearly favored the work of her husband, considered the more serious artist by the male critics and gatekeepers of the art world.

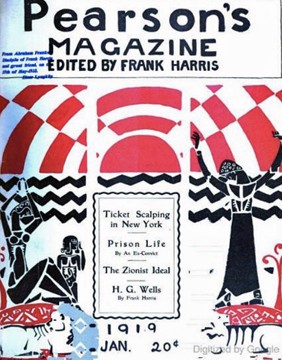

Aside from painting, the Zorachs collaborated in many media, including poetry, textiles, and sculpture. Their linoleum cuts and woodcuts were featured in Playboy, a Greenwich Village literary magazine edited and published by Egmont Arens from 1919 – 1925 (The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door). Their closeness and the relative success of their partnership interested the art world. A short piece about their bond was published in Pearson’s Magazine in April 1919: “It is interesting, this marriage of two artists, both working in form and color, both modern, intensely devoted to their work and to nothing else except each other and their young two children” (F.H. 265). William is described as “a Russian Jew” while Marguerite is “an American of New England stock.” The author of the piece admires the work of the Zorachs, particularly the magazine covers they produced for Pearson’s, and considers them both quintessentially modern. We also get an idea of Marguerite’s own philosophy of art in a long quote about her style:

I have no artistic creed or formula. I have no fixed aim to which I am bending every energy. I have made no wonderful or new artistic discovery. Perhaps I have not even a new vision…In so far as my life is rich in emotional and intellectual experiences, actual or in imagination, in so far as I seek for a deeper and more comprehensive grasp of things, in so far I shall have material from which to create.

Marguerite and William had a son, Tessim (1915 – 1995), who became a serious collector of pre-Columbian art, and a daughter, Dahlov Ipcar (1917 – 2017), a successful painter and illustrator. Marguerite turned her focus to textiles after the birth of her children, mostly because the expensive commissions could fund her family’s lifestyle. Describing their early years of financial hardship, William noted in his autobiography, Art is My Life:

We survived these years by never spending a cent on anything that was not essential...we saw that there was always money for materials...we made our own canvases...used the stretchers over and over, rolling up the finished pictures. When desperate we painted on both sides of the canvas (cited in Colleary 24).

Nevertheless, the Zorachs managed to buy a house in Maine, where they would spend many happy summers:

In 1923 my parents were able to buy a farm in Maine for very little, and after that we spent our summers there in Robinhood village on Georgetown Island. Our old 1820 farmhouse was large. My mother papered, painted, and furnished it with antiques which at that time cost much less than up-to-date furniture. She decorated the living room walls with a mural of leaves and animals and nude figures, all done in green. She also put extensive flower gardens in around the house, as well as a large vegetable garden. My father converted an old toolshed into a studio. There were 28 acres of fields and woods, and later my parents bought an adjoining farm of 65 acres, where I now live (Ipcar 2011).

They had first traveled Georgetown Island in 1922 to visit French sculptor Gaston Lachaise and his American wife, who were living in a sort of artists’ colony with painter Marsden Hartley and photographers Paul Strand and Gertrude Kasebier, among others (Weisgall).

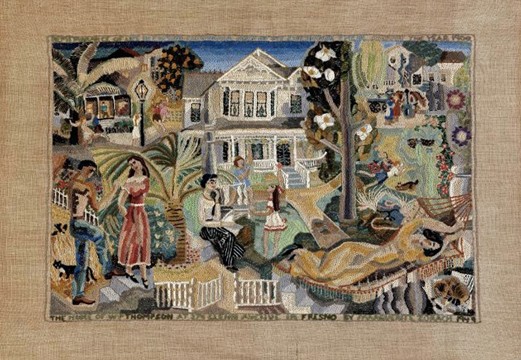

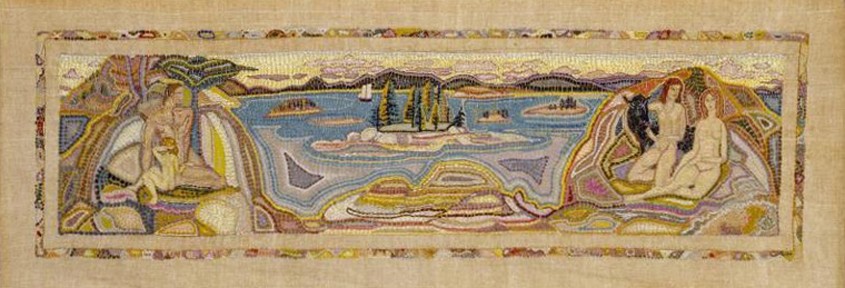

Records show that the sale of Marguerite's textiles accounted for the majority of the family income in the 1920s (Burk, Clark). Autobiographical elements and a “focus on relationships, especially those between male and female, and between parent and child” imbued her works in the interwar period (Bianco). Having been introduced by Edith Halpert of the Downtown Gallery in New York City, Marguerite and her family even visited the Rockefellers. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller commissioned an $18,000 tapestry from Marguerite, "a sum that allowed the Zorachs to continue their work as artists and also provided for their two young children" (Pollock 129). The tapestry "The Family of John D. Rockefeller Jr. at their Summer Home, Seal Harbor, Maine (1929 – 1932)," took a year to design and three years to execute.

Monumental in concept and scale, Marguerite Zorach’s embroidered portrait, “The Family of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. at their Summer Home, Seal Harbor, Maine 1929 – 1932,” features emblematic references to family members and their recreational pastimes in and around The Eyrie, their Seal Harbor residence. The tapestry is a celebration of the Rockefeller vision that helped shape Acadia National Park and preserve the beauty of Mount Desert Island for future generations (Mount Desert Islander).

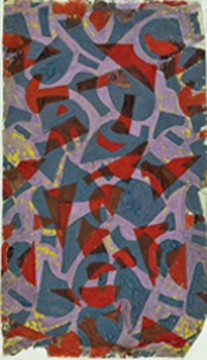

In addition to her tapestries, Marguerite also designed clothing, accessories like hats and handbags, and vibrant patterns for fabric. She was an officer of the Society of Independent Artists (1922 –1924) and served as the first president of the New York Society of Women Artists (1925), founded to provide exhibition space for women modernists. Like so many other artists, Thompson Zorach also participated in the WPA’s Depression-era work, painting two murals for Fresno post offices and one for the Peterborough, New Hampshire post office.

Marguerite taught watercolor in 1938 –1939 at the New School for Social Research, and she was a visiting artist at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture every summer from 1946 to 1966, as well as a member of their board of governors from 1960 to 1968 (Fowler 7 n. 15). When fellow Girls’ Art Club alumna Mildred G. Burrage founded the Maine Art Gallery in Wiscasset in 1957, Thompson Zorach and her daughter Dahlov Ipcar served as some of the earliest board members. In 1964, Bates College awarded Marguerite an honorary doctorate in Fine Arts.

Marguerite Thompson Zorach was active and productive until she died at the age of 81 on June 27, 1968, two years after William passed. The Zorachs' legacy was carried forward by their children, who donated many of their parents' works to museums in the U.S. and elsewhere. The family papers were deposited at the Smithsonian.

Sources

- Ashby, Chloe. "Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and Her Contemporaries review – the artists who refused to obey." The Guardian, November 5, 2019.

- Bianco, Jane. “Marguerite Zorach—She Achieved Balance in Her Life.” Maine Arts Journal, Summer 2019.

- Binckes, Faith. Modernism, Magazines, and the British Avant-garde: Reading Rhythm, 1910-1914. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Bowdoin, W.G. “The Zorachs Jointly Show at Daniel Gallery.” The Evening World, March 30, 1918, p. 10. Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

- Burk, Efram L., ed. Clever Fresno Girl: The Travel Writings of Marguerite Thompson Zorach (1908 - 1915). University of Delaware Press, 2008.

- Burk, Efram L., "The Graphic Art of Marguerite Thompson Zorach." Woman's Art Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, Spring-Summer 2004, pp. 12-17. JSTOR.

- Clark, Hazel. "The Textile Art of Marguerite Zorach." Woman's Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Spring - Summer 1995, pp. 18-25. JSTOR.

- Colleary, Elizabeth Thompson. "Marguerite Thompson Zorach: Some Newly Discovered Works, 1910-1913." Woman's Art Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, Spring - Summer 2002, pp. 24-28. JSTOR.

- F.H. “Mr. and Mrs. Zorach: Artists.” Pearson’s Magazine, vol. 40, no. 6, April 1919, p. 265. Google Books.

- Fowler, Cynthia. Early American Modernism and Craft Production: The Embroideries of Marguerite Zorach. PhD Dissertation, Art History, University of Delaware, 2002.

- Fowler, Cynthia. The Modern Embroidery Movement. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- “Fresno Artists Are Given Recognition.” The Fresno Morning Republican, August 7, 1910, p. 3. Newspapers.com.

- Heller, Jules and Nancy G. Heller. North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge, 2013, pp. 598-599.

- Hoffman, Marilyn Friedman. Marguerite and William Zorach: The Cubist Years. Hanover, NH: Currier Gallery of Art, 1987.

- “How Things Look to Mr. and Mrs. Zorach: Artists.” The Butte Miner, February 25, 1917, p. 33. Newspapers.com.

- Ipcar, Dahlov. "My Family, My Life, My Art." Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. 2011.

- Kennedy, Kate. Maine's Remarkable Women: Daughters, Wives, Sisters, and Mothers Who Shaped History. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, pp. 92-102.

- Rhythm: art, music, literature 4, Spring 1912, St. Catherine Press, London.

- Little, Carl. The Art of Dahlov Ipcar. Down East Books, 2010.

- “Marguerite Thompson, Futurist. Her Work Is Winning Attention.” The Fresno Morning Republican, October 27, 1912, p. 22. Newspapers.com.

- “Modern Art School.” International Studio, vol. 61, no. 422, April 1917, p. 11. Google Books.

- Nicoll, Jessica and Roberta K. Tarbell, Marguerite and William Zorach: Harmonies and Contrasts. Portland, ME, Portland Museum of Art, 2001.

- Nicoll, Jessica. "To Be Modern: The Origins of Marguerite and William Zorach's Creative Partnership, 1911-1922." Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. 2011.

- "Rockefeller Tapestry Talk Planned." Mount Desert Islander, August 18, 2017. Lifestyle

- “The Part Played By Women”: The Gender of Modernism at the Armory Show.

- “Society.” The Fresno Morning Republican, December 1, 1912, p. 7. Newspapers.com.

- Special to The Republican. “Marguerite Thompson Reaches San Francisco; Will Exhibit Paintings.” The Fresno Morning Republican, April 25, 1912, 1. Newspapers.com.

- Tarbell, Roberta K. Marguerite Zorach: The Early Years, 1908-1920. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1973.

- Tarbell, Roberta K. “Review: Marguerite Zorach: An Art-Filled Life.” Essays by Jane Bianco, Betsy Fahlman, and Cynthia Fowler, Farnsworth Art Museum, 2017.

- Untitled article. The Fresno Morning Republican, October 20, 1912, p. 7. Newspapers.com.

- Weisgall, Deborah. “Marguerite Zorach: Georgetown Goes Modern: The Modern Art Movement Meets an Island Community.” Maine the Magazine, July 2011.

- “Zorach.” The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door: A Portal to Bohemia, 1920-1925. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- Zorach family papers. Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- "Zorach, Marguerite T." Biography courtesy of the Caldwell Gallery, InCollect.

- Zorach, William. Art Is My Life. Cleveland, Ohio: World Publication Co., 1967.