Alice E. Rumph, 1877 – 1957

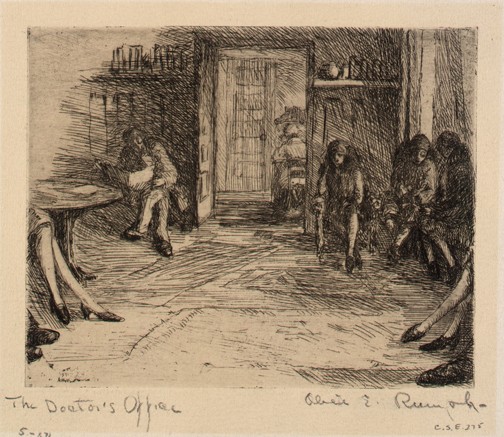

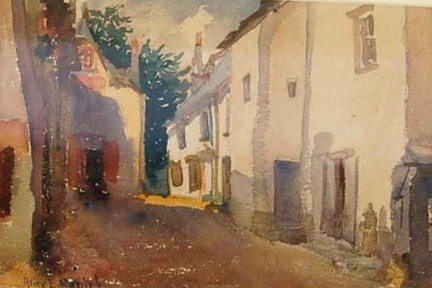

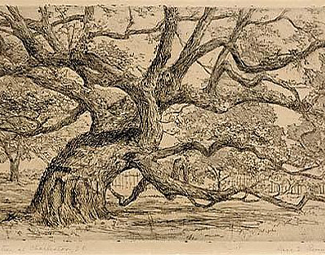

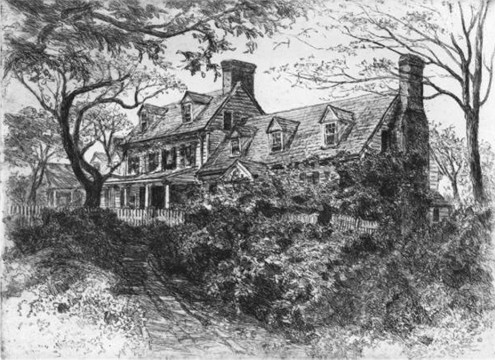

Reid Hall owns an etching by Alabama artist Alice Edith Rumph representing a view of the rue de Chevreuse building through the iconic gate that separates the courtyard from the gardens. We do not know when this etching was given to Reid Hall but it was exhibited at the 1903 American Woman's Art Association show and was likely executed during Rumph’s stay at the Girls’ Art Club from 1900 – 1902. In 1926, Rumph again exhibited this etching, at the annual exhibition of the American Fine Arts Society in New York City. It was described in The Birmingham News as “a ‘before dinner’ inspiration caught from the late afternoon sun on the picturesque windows of the old buildings, in which she lived for two winters” (January 31, 1926, 28).

Alice Edith Rumph was born in 1877 in Rome, Georgia to Cornelius Mandeville Rumph and Mary M. Mazyk Rumph (née Hume). She could trace her ancestry to the eighteenth century, when her great-great-grandfather, David Rumph, a German-Swiss immigrant, was deeded 100 acres of land near Charleston, South Carolina by England’s King George III (Montgomery Advertiser, October 24, 1902, 11).

Rumph began drawing as a young woman and shared the drawing honor with her classmate Lucy Coleman Dennis at the Birmingham High School graduation ceremony in 1895 (Montgomery Advertiser, May 18, 1895, 3). She then studied at the Birmingham Art School for several years. In 1900, Alice won a scholarship from R.S. Munger, owner of the Continental Gin Company, a cotton-gin plant with which her father had long been affiliated. Rumph traveled to Europe in April 1900 to study art and launch her career.

After touring London and Berlin, Rumph settled in Paris at the American Girls' Art Club. She enrolled at the Académie Colarossi in fall 1900 but was not entirely satisfied with her Parisian academy experience. In her own words:

[... I] found many surprises and some disappointments awaiting me among its academics [sic]. There I studied among students of all nationalities in big, badly ventilated studios, and learned to know the French masters of today that I had heard so much of. Morning was always my time for work, while afternoons generally found me tired out, and so sick of the studio that I fled to the open air for refuge. It was then we took long rambles through the city, sometimes walking, but oftener on the top of a clumsy omnibus that rattled through the broad boulevards and narrow streets (cited in Ingham 127).

Ingham reports that Rumph eventually decided to work on her own, outside of the Académie context, after several miserable months:

Work goes on in peace until the critic arrives and even then he is not half so bad as he is in a school with forty other pupils before him when he has finished with you. One long winter working thus in perfect freedom made me wonder why I had not found that haven long before (cited in Ingham 127).

While in Paris, Rumph’s watercolor "Devant la fenêtre" was exhibited at the 1901 Salon des artistes français at the Grand Palais. It was later shown in 1902 at the American Watercolor Society in New York City, and at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905. Rumph was so excited about having one of her works accepted into the Salon that she wrote a letter from the Girls' Club to a friend, gushing about this honor. The letter was partially reprinted in The Birmingham News on May 2, 1901:

I am writing tonight to tell you that congratulations are in order, for I am in the "Salon" […] I am duly elated over my success and all the more because I have absolutely no influence, having none of the prestige that some of the big schools give, as I have, as you know, worked in Garrido’s class, which is a private one. Everyone is congratulating me and saying how glad they are, because so many have been refused this year. Now I feel that my year’s work has been well crowned and I can depart on my trip to Italy with a clean conscience as well as an additional portion of self-esteem (cited in Ingham 5).

After nearly two years in Europe, Rumph returned to Birmingham in June 1902 to begin a career in art education. She briefly studied illustration in 1904 at the Chase School in New York City (Ingham 128). Rumph published a full-page account of her studies and travels abroad in The Birmingham News on August 2, 1902, describing her life in France, her journeys to Italy, Holland, Germany, England, and Switzerland, and her brief academy training with Prinet, MacMonnies, Mucha, and other teachers. The most poignant language was reserved to describe Paris, her adopted city:

And so we come back to Paris, which we find just the same gay, beautiful, encouraging, disheartening, flattering, indifferent, busy, idle, heart-breaking, joyous Paris. Paris, with its thousands of rich, thousands of poor, thousands of comfortable, and thousands of destitute—and thousands of students that sing in its streets, and slave in its studios, that ramble in its gardens, and eat at cafes, and dance at balls, and find themselves happy today and downcast tomorrow—and yet, we are never ready to leave, no matter what treatment we receive at its hands (cited in Ingham 3).

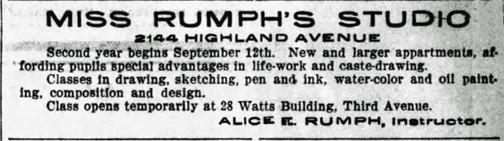

Rumph quickly settled back into life in the United States. She taught at the Margaret Allen School in Birmingham (ca. 1904-1911), and briefly operated her own studio in the Watts Building, teaching oil painting, illustration, and sketching.

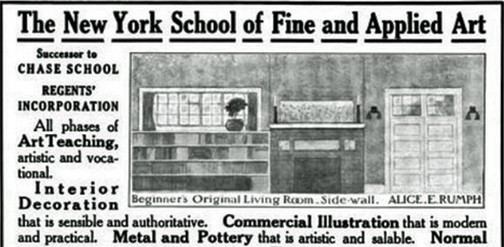

After completing a degree around 1911 at the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts (which later became the Parsons School of Design), she worked for a few years as a decorator, and then taught at Hollins College in Roanoke, Virginia in 1916, St. Genevieve's College in Asheville, North Carolina in 1918, and at other private establishments. While at St. Genevieve’s, Rumph visited a “reclamation camp for broken down soldiers” who were recovering from shell wounds or the effects of German mustard gas attacks, as well as the Azalea tuberculosis camp near Kenilworth, also filled with soldiers on the mend (Asheville Citizen-Times, August 25, 1918, 17). She planned to read to the convalescing soldiers in an effort to ease their suffering.

Rumph ended her career in education at Miss Beard’s School for Girls in Orange, New Jersey, where she taught from 1922 – 1942, eventually serving as chair of art. Throughout her life, she regularly returned to France with colleagues and groups of art students. In July 1927, for example, the Atlanta Constitution noted: "Alice E. Rumph, Carrie L. Hill, and others, are painting in Normandy and other picturesque spots" (4).

In addition to teaching future generations of women artists, Rumph continued sketching, etching, painting, and exhibiting her work. In 1908, she founded the Birmingham Art Club along with artists Della Francis Dryer, Willie McLaughlin, and Mamie Holifield Montgomery. The club hosted exhibitions, offered educational activities, and was the "[...] driving force behind the establishment of the Birmingham Museum of Art" (Knight 32).

Another former 4 rue de Chevreuse resident and Birmingham Art Club member was Lucille Sinclair Douglass, also an etcher. Rumph and Douglass shared a studio together in New York City in the 1930s (Ingham 134). The Birmingham Art Club sponsored an exhibition of Rumph’s work in 1925, featuring oils, watercolors, sketches, and etchings, mostly of her travels in the United States, France, and Italy. The exhibition received a rave review in The Birmingham News on March 29, 1925, which declared: “Miss Alice Rumph has always done beautiful work” (18).

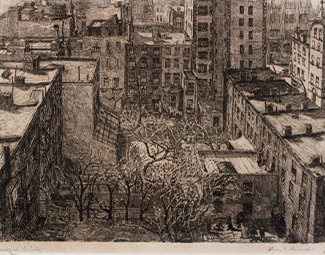

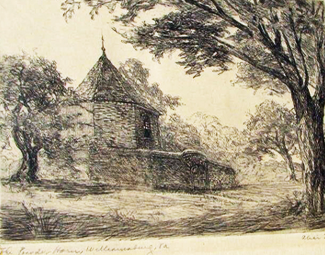

Though it is unclear whether or not the two Alabama artists and former Girls’ Art Club residents knew each other, both Anne Goldthwaite and Alice Rumph were featured in a major exhibition of contemporary prints at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1934. The Birmingham News reported on August 5, 1934 that Rumph’s etching “In the White Abbey” appeared alongside Goldthwaite’s etching “On East Tenth Street” and Goldthwaite’s lithograph “The Water Hole.” The exhibition featured works by artists from 21 countries in North America, Europe, and Asia (25).

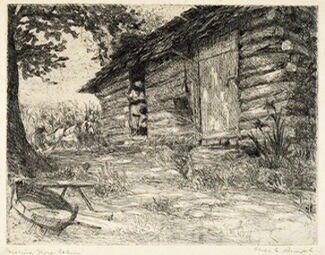

Architecture always featured prominently in Rumph’s work. She earned most of her commercial success during her later years by producing detailed etchings of historic American buildings. Around 1934, she created a series depicting landmarks in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. She worked out a deal with the John D. Rockefeller Library and Foundation for her etchings to be sold in the Colonial Williamsburg gift shop (Ingham 136). In 1939, Rumph also contributed to the restoration of Savannah's historic Telfair Family Kitchens:

"Alice Rumph, the well-known and distinguished American artist, [...] upon seeing the restored Telfair Family Kitchens in the Art Academy of Savannah, sought the privilege of making some drawings. And she has presented two exquisite etchings of the east kitchen, one to Charles Ellis, president of the Telfair trustees and the other to the academy!" (Cone 46).

In the last decade of her life, Rumph and her fellow Birmingham Art Club founders saw their cherished dream come true: the Birmingham Museum of Art opened to much fanfare with a $2 million collection in 1951. Naturally, Rumph and the other club founders were celebrated at the museum’s opening party, and a photo of the four smiling, triumphant women was published in The Birmingham News (April 9, 1951, 5).

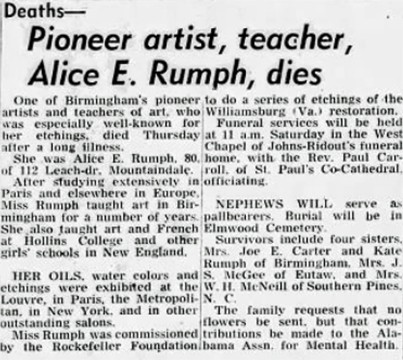

Alice Rumph died at the age of 80 in 1957. Her obituary, published in The Birmingham News on August 30, 1957, fittingly described her as a pioneer artist and teacher (35):

Sources

- "Alice Rumph Drawing Honor." The Montgomery Advertiser, May 18, 1895, p. 3. Newspapers.com.

- “Art in the Home: Pleasing Lecture by Miss Alice Rumph.” The Birmingham News, March 8, 1911, p. 10. Newspapers.com.

- “Art League Sales Reach $335 Total.” The Atlanta Constitution, July 3, 1927, p. 4. ProQuest.

- Barnwell, Ellen St. John. "Southern Scenes Depicted in Works Of Dixie Artists Now on Exhibit." The Atlanta Constitution, November 6, 1938, p. 2A. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Beard School Glee Club, Of Orange, to Give Play: The Mikado To Be Presented There Next Friday." New York Herald Tribune, April 21, 1935, p. C14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Birmingham Society." The Nashville American, April 8, 1900, p. 18.

- Caldwell, Lily May. “Birmingham Art Museum Opens with $2,000,000 Collection on Display.” The Birmingham News, April 9, 1951, p. 5. Newspapers.com.

- Cone, Kate Parker. "Artist Makes Etchings of Telfair Kitchens." The Atlanta Constitution, May 7, 1939, p. SM2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Dalrymple, Dolly. “Former Birmingham Painter’s Work Shown Under Auspices of Art Club.” The Birmingham News, March 29, 1925, p. 18. Newspapers.com.

- 5 Liners Arrive To-day From European Ports." New York Herald Tribune, September 13, 1926, p. 12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “From Birmingham.” Montgomery Advertiser, May 18, 1895, p. 3. Newspapers.com.

- Ingham, Vicki Leigh. Art of the New South: Women Artists of Birmingham, 1890-1950. Birmingham Historical Society, 2014.

- Knight, Elliot A. Alabama Creates: 200 Years of Art and Artists. University of Alabama Press, 2019.

- “Miss Alice Rumph Exhibits Paintings in New York.” The Birmingham News, January 31, 1926, p. 28. Newspapers.com.

- “Miss Alice Rumph Talks of Reclamation Camp at Asheville.” Asheville Citizen-Times, August 25, 1918, p. 17. Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Rumph to Address Club." New York Herald Tribune, February 26, 1936, p. 19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Music and Art Notes.” The Birmingham News, August 5, 1934, p. 25. Newspapers.com.

- “Painted Scenes for Rubaiyat.” The Birmingham News, February 18, 1914, p. 8. Newspapers.com.

- "Pioneer Artist, teacher, Alice E. Rumph, Dies." The Birmingham News on August 30, 1957, p. 35. Newspapers.com.

- Rumph, Alice. “Miss Alice Rumph Tells of Her Work and Travels While Two Years Abroad.” The Birmingham News, August 2, 1902, p. 3. Newspapers.com.

- “Social.” The Birmingham News, May 2, 1901, p. 5. Newspapers.com.

- “Society and Personal.” Asheville Citizen-Times, September 15, 1918, p. 8. Newspapers.com.

- “Some Old Documents.” The Montgomery Advertiser, October 24, 1902, p. 11. Newspapers.com.

- "Water Color Exhibition: Real Atmosphere Evident at Corcoran Corcoran Exhibit." The Washington Post, February 25, 1934, p. SM11. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.