Helen Josephy, 1899 – 1984

Helen Josephy was born in Marietta, Ohio to a Jewish family in 1899. Her father, Joseph Josephy, of German ancestry, had moved from Indiana to establish a clothing store, named the Buckeye, in Marietta in 1896 (Siewers 26). Josephy graduated from Smith College in 1921, where she had already tested her talents a writer, with an article for the Smith College Monthly (Leavitt, footnote 41). After graduation, she embarked on a long career as a journalist that took her all over the world:

"Helen Josephy is a perfect example of how to make yourself over,” explained local historian Jann Adams. “She started out as a journalist with The Marietta Times, then became an editor, an author, a mother and a mental health advocate. She kept remaking herself into the best version of herself. Her life teaches us to keep going after your visions, persist, make your way and make it happen (Patterson).

She first worked for her hometown paper, the Marietta Times, and was warned by a concerned colleague in 1923 that the local Ku Klux Klan chapter might harass her family (Shevitz 168-9). At the time, the family lived at 607 Third Street. While it seems that the family was never targeted, her father was the object of blatant anti-semitism:

With Joseph Josephy's business success and high level of civic and social involvement, it seemed only natural to several of his friends to nominate him for membership in the Marietta Rotary Club. Josephy's nomination caused a fracas in the Club that all but resulted in a major schism. So many of the members threatened to resign if a Jew were elected, that the nomination had to be withdrawn. Many of the members who threatened resignation were prominent Methodist churchgoers and, perhaps not so coincidentally, business rivals of Josephy (Siewers 31).

Helen left Ohio for Manhattan in the latter half of the 1920s to write for The New York Globe, The New York Evening Mail, then the New York Sun. She then moved to Paris, where it seems she remained for five years and resided at 4 rue de Chevreuse for an undetermined period of time. She first covered art and music events for the New York Herald, Paris edition, interviewing George Gershwin, Oscar Levant, Jack Dempsey, and Gloria Swanson, among others (Citizen Register, November 5, 1982, p. 25).

Paul Alfred Shinkman, a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune in interwar Paris (he wrote a column starting in November 1924 called "Latin Quarter Notes"), mentions Helen Josephy in letters home to his family, published in So Little Disillusion: An American Correspondent in Paris and London 1924 – 1931. In an October 12, 1924 letter, Shinkman describes inviting Josephy to dinner to celebrate his birthday:

[...] she is a reporter on the New York Herald, our deadly rival. She is a graduate of Smith, not too beautiful, but attractive, and has plenty of personality, and a lot of common sense. [...] For dinner we hit the Ritz – about the swellest outfit in Paris, where the King and Queen of Greece, counts, dukes, and all the rest show up! Dinner over about 10:30 p.m., we stepped into a taxi and whirled up to Montmartre for a taste of the so-called 'high life.' Stopped at a Russian cabaret, ordered champagne, and danced until about three. We had a great time (31-32).

Josephy left the Herald for Paris Vogue, where she remained only seven months: "I gave up my dream job for fashion, and I didn't like it at all. It wasn't my kind of thing" ((Citizen Register, November 5, 1982, p. 25).

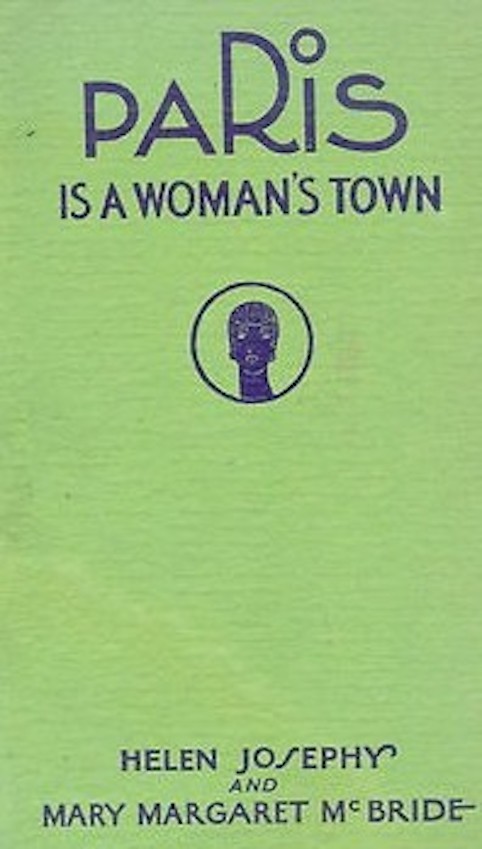

Instead, she began writing with Mary Margaret McBride, reporter for the Evening Mail who had come to Paris on an assignment for a magazine article (The Kansas City Star, May 29, 1930, p. 11) and would later become a radio celebrity under the name of Martha Deane. The two decided to collaborate on a new kind of Paris guide that was confined to the practical details of existence, "like early Fodor guides, which talked about shopping, where to stay, local customs, and interesting things to do" (Ware 140).

Their collaboration led to the 1930 publication of Paris is a Woman's Town, a fun, witty guide for women of all ages and interests. It covered every aspect of life in Paris, from shopping to dining to entertainment. Today, it gives modern readers a remarkable glimpse into interwar Paris from an American perspective:

Our idea of writing a book was to make it a little easier for women who dream and plan for their first trip to Paris and then are so awed by the strange language and customs that they miss half the fun of the trip. In order to tell them just what to do and what not to do, down to the very last detail, we had to do all the things first ourselves. Some of our experiences are very interesting (cited in Merrick 83).

Proudly displayed in Marietta bookstores, it was widely advertised in newspapers throughout the United States and made the bestsellers' list within two weeks of its publication (Siewers 30; Kansas City Star, August 17, 1929, p. 4).

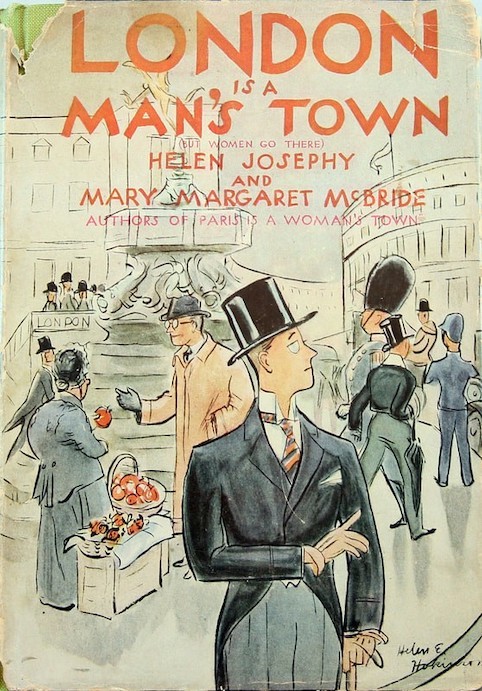

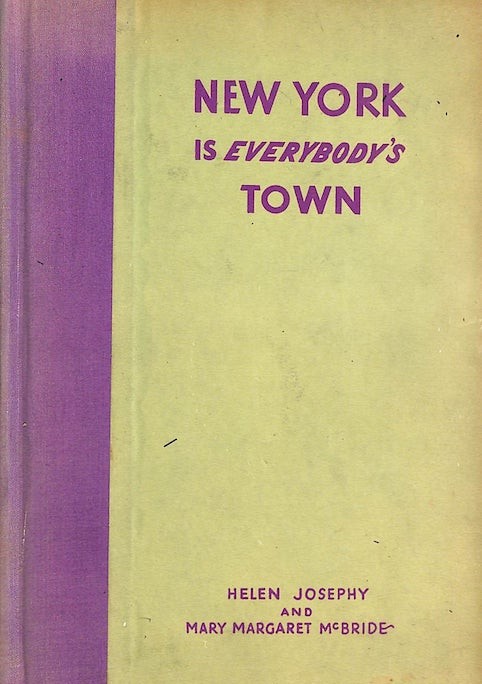

Josephy returned to New York where she wrote for the New York Sun, and, given the success of the Paris guide, she and McBride co-wrote several other guidebooks: London Is a Man's Town (But Women Go there) (1930), New York is Everybody's Town (1931), and Beer and Skittles – a Friendly Guide to Modern Germany (1932). The titles of the first two were directly lifted from Henry Van Dyke’s 1909 poem, “America for Me: “Oh, London is a man’s town, there’s power in the air; And Paris is a woman’s town, with flowers in her hair.” (Omaha World-Herald, June 15, 1930, p. 60). While the Paris and London guides enjoyed significant success, the others had much less appeal:

[…] the New York and Germany guides failed to find a market, hardly surprising in light of the deepening worldwide depression and Hitler’s rise to power. In fact, the worsening political situation in Germany was never even mentioned in the final guide, which in retrospect made its light tone even more incongruous (Ware 140).

In between writing and publishing, Josephy traveled extensively. On July 27, 1929, The New York Times reported that she had gone to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to offer official greetings from New York's mayor, James J. Walker. An earlier Times article from July 12, 1929 named Josephy as a travel writer sailing from Brooklyn to Brazil on the maiden voyage of the Sud Americano, the new steamer of the Linea Sud Americano, Inc. The July 12th article indicates that she was planning to gather material for a book on the Brazilian capital, much like she had done for Paris (and would do for London, New York, and Germany). It is unclear why she never published her Rio guide.

1930 finds her in Chicago, where she and Margaret were the guests of honor of the Chicago Tribune at a tea promoting their books on Paris and London. An April 30 Tribune article published at the same time describes her as "slender” with “eyes as black as sloeberries” (Coleman 14).

Helen undertook another voyage in June 1931, sailing to Germany on the Europa liner along with a number of luminaries that included Columbia University's president, Nicholas Murray Butler. Butler was planning to confer with European statesmen on behalf of the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, and it is likely that Josephy was present in her capacity as a journalist.

When Helen’s her father died in 1931, her mother and younger sister came to join her in New York (Siewers 33). She married writer Jesse Robison in 1932, with whom she would have two children.

In 1932, Josephy and McBride covered ski season in Germany for Harper's Bazaar (January 1932).

In 1935, Josephy was one of the founding editors of Mademoiselle, a new magazine for women of moderate income. An article in Time identifies her as a contributing editor:

Contributing Editor Helen Josephy, in charge of the beauty articles, invited Nurse Phillips to Mademoiselle's Manhattan office. Convinced of the young lady's good faith, the editors decided to take a sporting chance and see what could be done about her personal appearance in one week's time. Thus was launched a heroic course of beauty treatments and a smart circulation and merchandising stunt (October 26, 1936).

Josephy continued to collaborate with McBride when she became the first lady of radio journalism in 1934, becoming “[…] McBride's first legwoman on radio, the one who went out to check facts and often came up with tips for McBride" (Merrick 83). In 1936, she and McBride also published a semi-autobiographical story, Here's Martha Deane, of McBride's radio show (Columbia Missourian, June 27, 1949, p.4).

Later in life, Helen pursued many diverse paths, including volunteering for the Scouts and the League of Women Voters. In the 1950s, she worked for the U.S. military, producing booklets for the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS), meant to encourage women to join the armed forces. Her old friend Mary Margaret McBride published an article in the Los Angeles Times on Nov. 2, 1955 (which was widely reprinted in other U.S. newspapers) promoting Helen's work and encouraging young women to enlist, noting that she would do the same if she were of age.

In 1968, Josephy co-founded the Futura House in White Plains, New York, “a halfway house for discharged mental patients,” initially destined for women and opened to men in 1973. She was honored for the concept by the Westchester Ethical Humanist Society in 1982 (Daily Item, 1982).

According to her obituary in the Daily News, Helen Josephy Robison died on December 25, 1984 in the Bronx after a long illness. She was 85 years of age.

Sources

- Adams, Jann Kuehn. German Marietta and Washington Country, Arcadia Publishing, 2016, 128 pp.

- Coleman, Alta May. "Rudy Vallee Studies What Public Wants." The Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1930, p. 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Futura Founder Honored.” The Daily Item, July 2, 1982, p. 25. Newspapers.com.

- “Futura House to Benefit from Drama Showing. The Daily Item, November 4, 1968, p. 12. Newspapers.com.

- “Futura House Annual Meeting Set.” The Herald Statesman, May 5, 1970, p. 27. Newspapers.com.

- "Gets Walker's Greetings." New York Times, July 27, 1929, p. 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Josephy, Helen. "The Way of Man." Smith College Monthly, April 1921, pp. 217-224.

- Josephy, Helen and Mary Margaret McBride. Paris is a Woman's Town, Coward-McCann, 1929.

- Josephy, Helen and Mary Margaret McBride. London is a Man's Town, Coward-McCann, 1930.

- Josephy, Helen and Mary Margaret McBride. New York is Everybody's Town, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1931.

- Josephy, Helen and Mary Margaret McBride. Beer and Skittles, a Friendly Modern Guide to Germany, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1932.

- Leavitt, Judith Walzer. Women and Health in American: Historical Readings. University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

- Maack, Mary Niles. "American Bookwomen in Paris in the 1920s." Libraries & Culture, vol. 40, no. 3, Summer, 2005, pp. 399-415. JSTOR.

- McBride, Mary Margaret. "Mary Margaret M'Bride Says- She'd Enlist If of Age." Los Angeles Times, November 2, 1955, p. B4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Meeting Society and Problems Halfway.” The Daily Times, April 27, 1986, p. 45. Newspapers.com

- Merrick, Beverly G. “From Ghosting to Free-Lancing: Mary Margaret McBride Covers Royalty and Radio Rex for the ‘Saturday Evening Post, Woman's Home Companion’, and ‘Cosmopolitan’ (1925—1935).” American Periodicals, vol. 9, 1999, pp. 74–96. JSTOR.

- "News of Americans in Europe." New York Herald, Paris, August 24, 1933, p. 4. Gallica.

- “Obituaries: Helen J. Robison.” Daily News, December 28, 1984, p. 206. Newspapers.com.

- Patterson, Janelle. "Women's Museum Sees Growth Ahead." Marietta Times, August 30, 2017, n.p.

- Robison, Helen, J. “Report of the National Conference on Equal Pay, March 31 – April 1, 1952” Bulletin of the Women’s bureau, no. 243, 1952. Google Books.

- Robison, Helen, J. Careers for Women in the Armed Forces, Special Services and Publications Division, Department of Defense and Department of Labor, 1955. HathiTrust.

- "Sails on Maiden Voyage." New York Times, July 12, 1929, p. 46. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Shevitz, Amy Hill. Jewish Communities on the Ohio River: A History. Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2007. Google Books.

- Siewers, Amy Hill. “Judaism in the Heartland: The Jewish Community of Marietta, Ohio (1895-1940).” The Great Lakes Review, vol. 5, no. 2, Winter 1979, pp. 24-35. JSTOR.

- Shinkman, Paul. So Little Disillusion: Letters, Articles, Diaries of Paul Shinkman, an American correspondent in Paris and London, 1924-1931. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1983.

- Ware, Susan. It's One O'Clock and Here is Mary Margaret McBride: A Radio Biography, NYU Press, Feb 7, 2005, 304 pp.