Julia Gulliver, 1856 – 1940

Julia Henrietta Gulliver was a philosopher, professor, and educational pioneer, who became the second woman in U.S. history to earn a doctorate in philosophy in 1888. Born to a progressive family in Connecticut in 1856, Gulliver enrolled in the first graduating class of the newly-founded Smith College in 1875. Soon after earning her PhD (also from Smith), Gulliver moved to Rockford, Illinois to serve as Head of the Department of Philosophy and Biblical Literature at Rockford Female Seminary (later renamed Rockford College and today known as Rockford University). During a teaching sabbatical, Gulliver traveled to Europe in 1892 and spent a year studying philosophy at the renowned University of Leipzig, distinguishing herself as the only woman in a department of 200 men. This year in Germany enabled her to also visit Paris, where she stayed at the American Girls' Art Club. Her sister, Mary Gulliver, was a budding artist who lived and worked in Montparnasse.

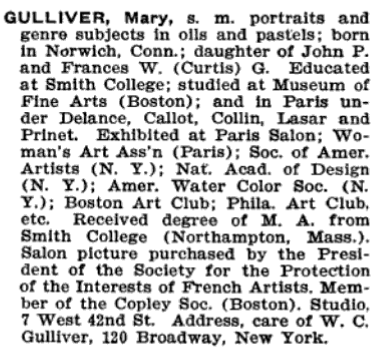

Very few images of Mary Gulliver's work are extant. Records show that Mary exhibited a painting at the 1902 Salon des artistes francais, "A Dutch Interior," and that she participated in an exhibition at 4 rue de Chevreuse around the same time, but further details are scarce. The catalogue from the 1902 Salon indicates that Mary's address was 54 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, right at the intersection of the rue Vavin. The 1905 Artists Year Book, produced by the Art League Publishing Association, tells us that Mary had been educated at Smith College and that she had studied in Paris under Whistler, Delance, Collin, and others at the Académies Delécluse and Colarossi, in addition to completing a course at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School.

A friend of Julia and Mary Gulliver named Mary Rogers Williams, an Impressionist painter whom scholar Eve M. Kahn has dubbed "the Mary Cassatt you've never heard of," also lived in Paris at the turn of the twentieth century. Her letters home are filled with details about art student activities and though she did not live at the American Girls' Art Club, choosing instead her own studio on rue Boissonade, she did exhibit her work at two of the Club's annual exhibitions, 1898 and 1907. The 1898 show featured three pastel landscapes by Williams who claimed that the director, Julia H.C. Acly, "quite went into raptures over my 'little Connecticut views.'" Williams also reported that Miss Acly "'wishes the club to purchase some of my pastels and would like to have one herself also knows of another lady who would like one.'" Her cynical view of the art market kept Williams from being disappointed when none of her works were bought: "I rather think she meant they'd all like one if I were giving them away. I find that these women over here will pay cheerfully twenty-five dollars for the latest thing in corsets but they consider ten dollars too much to pay for a picture. Queer old world, isn't it'" (as quoted in Kahn 109).

Williams criticized the Club in her letters: "It was smelly and dirty and chilly and too many females. ...Isn't it sad to be so fastidious, and to mind smells and bad food. It makes living in Paris expensive, for you have to pay to be clean. ...would not live there if they'd give me the whole place" (Kahn 107). Though it's clear that Mary found living at the Club undesirable, she called on the Gullivers socially and enjoyed the afternoon teas sponsored by Elisabeth Mills Reid. Williams encountered Reid during one of these teas, describing her as "a plain, vivacious woman in an elegant gray gown" (Kahn 107). She also saw one of the neighborhood's most prominent residents and atelier masters at a Club tea: "who do you think came and looked in at the door - Mr. Whistler!...He looked much older than when I saw him last" (Kahn 107). Neither Mary nor Julia Gulliver recorded eyewitness accounts of their time at 4 rue de Chevreuse so it is fortunate that Williams' letters shed some light on the early days of the Club.

Upon returning to the United States after her year in Europe, Julia Gulliver resumed her position at Rockford College. In 1902, she became the college's seventh President, serving in that capacity until her retirement in 1919. Once again following in her sister's footsteps, Mary Gulliver also returned to the U.S. and began her own career in education. She first taught drawing, painting, and art history at The Mary A. Burnham School for Girls in Northampton, Massachusetts before accepting the position of Head of the Department of Fine Arts at Rockford College in 1911 (Annual Catalogue of Rockford College, 1911, 14).

In her seventeen years as the president of Rockford College, Julia Gulliver exponentially increased the institution's endowment, secured its national accreditation, enhanced the curriculum for women by establishing programs in home economics and secretarial studies, and doubled enrollment (Townsend, American National Biography online). Her success as an administrator led to accolades: the French government made her an Officier d'Académie in 1909 and she was awarded an honorary LL.D. in 1910 from her alma mater, Smith College, along with Julia Ward Howe, grandmother of artist and former Girls' Club resident Caroline Minturn Hall (Walhout 74). Gulliver maintained a lifelong close friendship with Rockford College alumna Jane Addams, social activist, founder of Hull House, and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, though the two women had differing views on WWI (Gulliver actively supported the war; Addams was an avowed pacifist).

Though Julia Gulliver's duties as an administrator monopolized her attention, she still found time to give lectures and to publish philosophical scholarship while at Rockford. Her 1917 book, Studies in Democracy, argued for equality of opportunity in democracy, a radical viewpoint in the early 20th century. In a 1913 address to the Chicago College Club entitled, "Why Should a Girl Have a College Education and What Will It Do For Her?," Gulliver passionately advocated for women's rights to higher education as "a part of this great world movement for the liberation of humanity" (Gulliver 7). Though it could not have been easy working in a field as dominated by men as philosophy, Gulliver persevered, becoming one of the first fifteen women to join the American Philosophical Association.

It is unclear how she spent the last two decades of her life as a retired woman in Eustis, Florida, but she was once again accompanied by her sister Mary. She died in 1940 at age eighty-four, and her passing was marked by an obituary in The New York Times (July 28, 1940).

Sources

- Annual Catalogue of Rockford College. Rockford, Illinois: The Clark Company Press, 1911-1912. Google Books.

- The Artists Year Book. Chicago: Art League Publishing Association, 1905, p.78. Google Books.

- Fine Art Today. "Mary Rogers Williams: Why She Matters," Fine Art Connoisseur, December 9, 2019.

- Gulliver, Julia H. "Why should a girl have a college education and what will it do for her? : a Rockford College point of view : address before the Chicago College Club, December 13, 1913." Gerritsen Collection.

- Kahn, Eve M. Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019.

- Société des artistes français. Catalogue illustré de Salon de 1902. Paris: L. Baschet, 1902. Internet Archive.

- Special to The New York Times. "Julia H. Gulliver, Educator, is Dead: Rockford College President, 1902-19, Stricken at 84." New York Times, July 28, 1940, p. 30.

- Townsend, Lucy Forsyth. "Gulliver, Julia Henrietta (1856-1940), college president and philosopher." American National Biography Online. February, 2000. Oxford University Press.

- Walhout, Donald. “Julia Gulliver As Philosopher.” Hypatia, vol. 16, no. 1, 2001, pp.72–89. JSTOR.