The Neighborhood, 1922 – 1939

The end of WWI brought about the return of a flourishing artistic community in Montparnasse. One can just imagine the exciting atmosphere around the University Women’s Club in the 1920s, when the so-called "Lost Generation" of American writers, artists, and intellectuals made their homes on the Left Bank.

The Lost Generation

Many painters, sculptors, and writers were regulars at the cabarets and brasseries on the boulevard Montparnasse and its surrounding streets. In Philip Greene's words, the neighborhood was "a drinkable feast" and scores of American characters were an important part of the scenery. Prohibition in the United States, the favorable currency exchange, and the relatively cheap cost of living in Paris attracted throngs of Americans, for whom France represented freedom of expression at many different levels. Montparnasse abounded in American-style bars and restaurants, dance clubs, and cabarets, all catering to the expatriates.

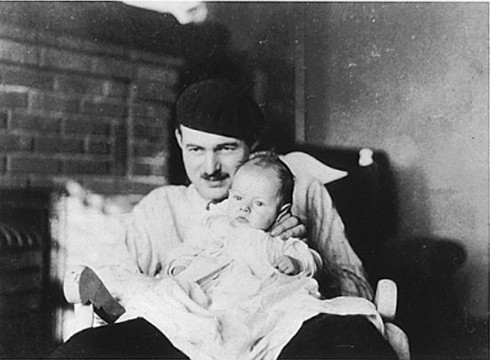

Ernest Hemingway describes many of the neighborhood’s hotspots in A Moveable Feast (1964), the account of his early years in Paris as a young journalist and writer. Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley Richardson, lived in a rented flat above a sawmill at 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs (long since demolished). When their son John, known affectionately as Bumby, was born in 1923, the Hemingways had him christened in 1924 at St. Luke’s Chapel, the ‘Little Tin Church,’ in the company of his godmother Gertrude Stein. Hemingway points out landmarks in A Moveable Feast like Ezra Pound’s apartment at 70 bis rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Chez Les Vikings, a cabaret and café once located in adjoining buildings at 29 and 31 rue Vavin, and his favorite place to write (and drink), La Closerie des Lilas, still open for business as of 2023 at 171 boulevard du Montparnasse.

Kiki (real name Alice Ernestine Prin) was another local celebrity, the so-called Queen of Montparnasse, who reigned supreme in artistic circles throughout the 1920s and 1930s. A cabaret singer and dancer by trade, she was also a portrait painter who served as a model for countless artists. Léger, Utrillo, Foujita, Man Ray, Cocteau, Modigliani, Picabia, Kisling, Clair, Mandel, and many others immortalized her carefree persona through visual interpretations of her face and body. Her scandalous autobiography shed light on the debauchery of the neighborhood. Kiki’s Memoirs, translated into English in 1930 by Samuel Putnam, were published by At the Sign of the Black Manikin Press, which was run out of a rare book shop of the same name on the rue Delambre by Edward Titus, husband of Helena Rubenstein. Judged to be too risqué by customs officials, the memoirs only made it to the U.S. until 1996. Kiki was such an outsize presence in the neighborhood that the young women living at Reid Hall would certainly have been aware of her, though she was likely too eccentric for their tastes. But she certainly took notice of them:

Montparnasse, so picturesque, so colorful! All the peoples of the earth have come here to pitch their tents; and yet, it’s all just like one big family. In the morning, you can see young fellows in wide trousers and fresh-cheeked young girls on their way to the art-schools, to Watteau’s, to Collarossi’s, the Grande Chaumière, etc. …Later the café-terraces begin to fill up, and pretty Americans eating oatmeal can be seen sitting side by side the French picons-citron. The crowd goes to look for a ray of sunlight at the cafés. The models meet one another there [...]. Montparnasse is a village that is as round as a circus. You get into it you don’t know how, but getting out again is not so easy! There are people who have got off by accident at the Vavin subway station, and who have never left the district again, have stayed there all their lives (175-176).

Peggy Guggenheim, who would become one of the greatest modern art patronesses of the 20th century, lived near rue de Chevreuse as a newlywed. She was a young socialite when she moved to Paris around 1920 to be with her first husband, Dada sculptor Laurence Vail, whose sister Clotilde performed English, Spanish, and French songs at Reid Hall in June 1928. The couple resided in Montparnasse and were friendly with all of the celebrities of the quarter: Man Ray, Kiki, Constantin Brancusi, Marcel Duchamp, and so on. Her autobiography, Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict, tells of their immersion in the entertainment venues surrounding Reid Hall: "We generally spent every night in cafes in Montparnasse. If I were to add up the hours I have whiled away at the Cafe du Dome, La Cupole [sic], the Select, the Dingo and the Deux Magots (in the Saint-Germain quarter) and the Boeuf sur le Toit, I am sure it would amount to years" (51).

Artist Haunts

Month in, Month Out, There Are Some 25,000 Americans in the City, Mostly in Montparnasse – at the Dome, the Dingo Bar, or Studying. There is a new name for the old, old Latin Quarter in Paris. Frenchmen call it the American quarter now and up and down its boulevards from Mich to Raspail, one sees American students, American Artists and American idlers. If you sit long enough at the Dome or the Rotonde they say you will see every American you have ever known. On summer evenings the college crowd "over" for vacation gathers at one or another of these renowned cafés for a glass of café au lait or something a little stronger. Older Americans come to visit haunts of their student days or merely out of a desire to see the old resorts of Victor Hugo and Anatole France. Montparnasse, the most American of the quarter, buzzes with American slang, American songs and American French. Around the corner from the Dome there is the Dingo Bar, where Charlie, a genial Texan, mixes cocktails and serves chili con carne for fifteen francs a plate and where almost any evening you can hear "My Old Kentucky Home" or "Who?" banged out on an old jazz-strewn piano surrounded by half a dozen Paris-Americans and perhaps one or two interested French flappers [...] (Pfalzgraf 10).

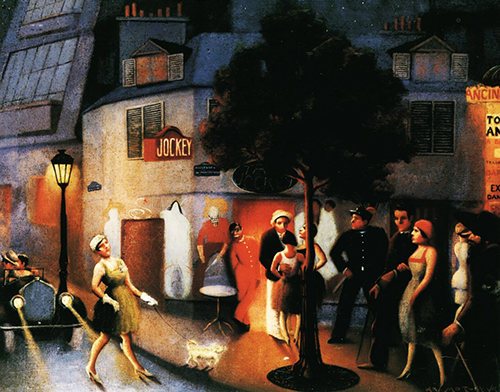

The first cabaret-club in Montparnasse, Le Jockey, was founded by the jockeys Miller and Copeland in 1922 or 1923 at 146 boulevard du Montparnasse, on the corner of the rue Campagne-Première. Soon after opening, Le Jockey became the center of a controversy when the wife of an American jockey (Nell Miller) harassed and had Kojo Touvalou Houénou ejected from the bar. He was a prince of the royal family of Dahomey who had served as a doctor in the French army during WWI. He had remained in Paris to earn a law degree and make connections with French intellectual elites. According to Hiler, the Jockey was ordered closed for "a long while" (cited in Atlas 3). Several months later, Touvalou was also kicked out of a dance club in Montmartre (Chatuant 2010, 245). These incidents led President Poincaré to admonish American visitors for their racist attitudes.

When the Jockey re-opened, Hiler was given permission to redecorate:

Then one day I went over to see Vernon Caughell and told him that if he would let me decorate the place I would make it go. So I was put in charge. I covered the walls with posters. I invited dark and white people to the place – every nationality, in fact. We even had a Chinese kitchen for the Chinese. Jazz and Negroes were being adopted by Paris then. The Jockey became a hangout for the elite. Clive Bell, Derain, Pascin, Foujita, Kisling, Jean Cocteau – everybody came to the place (cited in Atlas 3).

He designed the interior to resemble a Western saloon covered in posters and cartoons painted with shoe polish. It became a popular watering hole for Aragon, Hemingway, Kiki, Man Ray, Pound, and Tzara.

Around May 1935, Le Jockey, whose building had been condemned by the city of Paris, crossed the street to 127 boulevard du Montparnasse, on the corner of the rue de Chevreuse.

Le Jockey reflected the ethos of the bohemian "montparnos" (neighborhood regulars). Historian Jeffrey H. Jackson described the original club as:

[...] a small, dark, smokey, crowded nightspot [...] where customers had to squeeze past each other to find a few inches at the bar. Despite its lack of comfort, it was nevertheless one of the most fashionable destinations in Montparnasse. Named for the occupation of one of its proprietors, the Jockey featured "bizarre posters and other weird decorations" on the walls and ceilings along with paintings of "cowboys and Indians" by painter Hilaire Hiler, who occasionally played the piano. Sometimes, poetry and lectures accompanied the various musical entertainers, who passed the hat to collect tips (68).

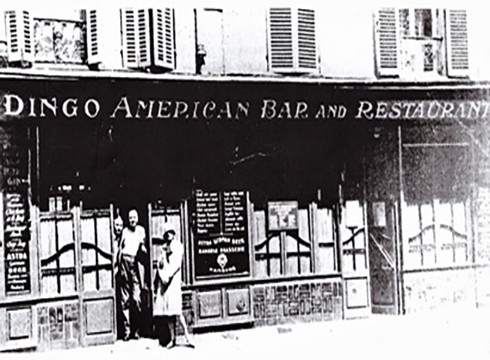

Located at 10 rue Delambre, the Dingo American Bar opened its doors in 1923. Regulars included dancer Isadora Duncan, who lived across the street, Kiki, Lady Duff Twysden, and shipping heiress Nancy Cunard. Hemingway first met F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Dingo in 1925.This Must be the Place, edited by Morrill Cody with an introduction by Hemingway, chronicles the life of the Dingo's long-time barman, Jimmie Charters. He reminisces about his encounters with the notable expatriates who ate, drank, and conversed within the walls of the different clubs and restaurants in which he worked: the Dingo, the Falstaff, the Trois et As, the Jockey, and le Parnasse. The book is illustrated by Hilaire Hiler, who encouraged Charters to publish his memoirs. The legendary bartender, originally from Liverpool, was known for his special concoctions, one of which was said to have certain effects on women who, after two drinks, would inevitably undress in public. These memoirs, which capture the ethos of the time in Montparnasse, did not age well, as they are sexist, homophobic, and racist.

![Postcard advertising The Jungle, on the corner of rue de Chevreuse, ca. 1928. ["The Jungle" postcard] Memorabilia, photos, etc. (from France), 1925-1926. Laura Lilian Brandt papers, College Archives, CA-MS-00303, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. Postcard advertising The Jungle, on the corner of rue de Chevreuse, ca. 1928. ["The Jungle" postcard] Memorabilia, photos, etc. (from France), 1925-1926. Laura Lilian Brandt papers, College Archives, CA-MS-00303, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.](/sites/default/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/pics/TheJungle_1927%20H490.jpg?itok=v58HdL8z)

According to L'Intransigeant, The Jungle (127 boulevard du Montparnasse, on the corner of the rue de Chevreuse future site of Le Jockey) opened on July 13, 1928 (2). It was one of several haunts where Kiki sang. It was decorated by Hilaire Hiler, who painted murals and played jazz in a number of the expatriate nightclubs of Montparnasse. He probably designed the postcard advertising the club, which resembles many of the anachronistic stereotypical characters he drew for an American circus (see Broca 23).

The Jungle was one of the Jockey’s main competitors and was famous for its black dancers (Jackson 69). Paul Cohen-Portheim described The Jungle as “tremendously hot, highly coloured, and African” (44).

One of the performers at The Jungle was jazz singer and dancer Zaidee Jackson, who came to Europe in 1927 and immediately gained popularity in London, Paris, and other cities. The newspaper L'Intransigeant advertised her début at The Jungle in June 1931 (Cabarets 5).

Between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, several large brasseries were established on the boulevard du Montparnasse. Teeming with artists of every medium and nationality, many of these brasseries exhibited paintings organized concerts and dances. The institutions listed below are still open in the twenty-first century and boast of the glory days of yesteryear in their brochures, place settings, advertisements, and decor.

The Dome: Established in 1897 at 108 bd. du Montparnasse.

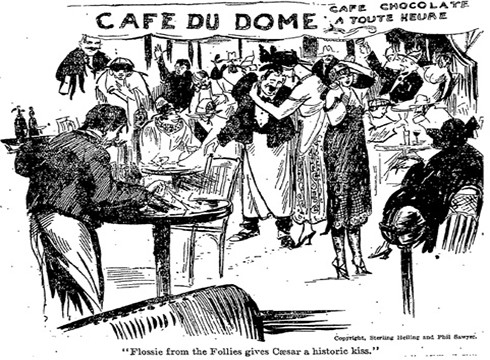

According to an article written by Sterling Heilig in the Baltimore Sun : "Before the war American girls were as scarce as hens' teeth at the Dome and never came unescorted. Now they file in and order their own drinks and smoke cigarettes, while some sport nice clean pipes" (June 8, 1924, FA1). The same article reports that during WWI, the Dome "filled up with American soldiers." It was also frequented by Lenin and Trotsky, Hemingway, Henry Miller, Samuel Beckett, Man Ray, Blaise Cendrars, and André Breton, to name a few.

La Closerie des Lilas: Established in 1903 at 171 bd. du Montparnasse.

In the 1920s, the Closerie showcased itself as "Le Café de la Société Artistique et Littéraire, française et étrangère (The Café of French and Foreign Artistic and Literary Society). The interior was decorated in 1922 and outfitted with an American bar. Apollinaire and Alfred Jarry met there and it was later patronized by the likes of James Joyce, John Dos Passos, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Paul Fort, Ernest Hemingway, André Breton, Michel Leiris, and Robert Desnos.

La Rotonde: Established in 1911 at 105 bd. du Montparnasse.

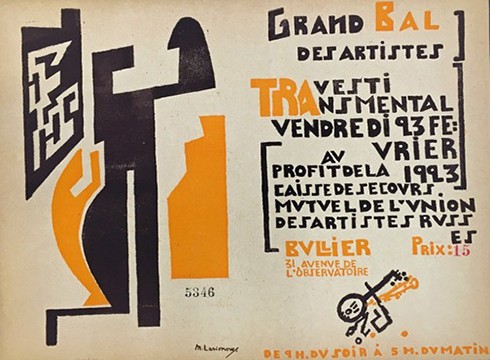

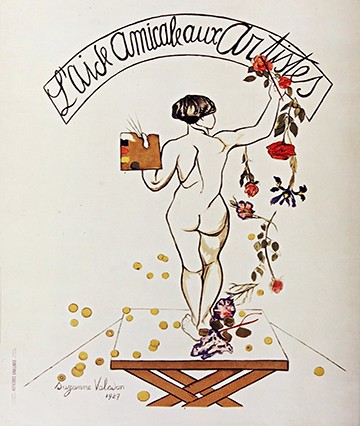

One of the regulars at La Rotonde was police captain Léon Zamaron. Known as an art enthusiast and advocate, Zamaron created an association, "Aide Amicale aux Artistes" (AAAA), and assisted foreign artists with obtaining visas, resident permits, etc. (Yagil 20). He received numerous paintings from such artists as Soutine, Modigliani, Utrillo, Chagall, Foujita, Valadon, Vlaminck, and Zadkine. In 1923, the AAAA partnered with the Union of Russian artists to organize an event that rocked the neighborhood, Le Grand Bal des Artistes Travesti-Transmental (see below).

Le Select: Established in 1923 or 1925 at 99 bd. du Montparnasse.

Known as the American bar, it was the first Monparnasse establishment to remain open all night. It attracted mainly Anglophone writers rather than visual artists.

La Coupole: Established in December 1927 at 102 bd. du Montparnasse.

The owners, Ernest Fraux and René Lafon, converted an old wood and coal warehouse measuring 1000m² into an art deco haven, with frescoes painted by Fernand Léger, Moïse Kisling, Marie Vassilieff, Henri Matisse, and many others. Legend has it that 2500 guests reveled throughout the night during its opening. La Coupole rapidly attracted numerous artists, including Picasso, Fujita, Giacometti, Zadkine, Derain, Léger, Soutine, Man Ray, Brassai, and Kisling. Georges Viaud, former head-waiter turned historian, rightly remarks: “If the tables could talk, they would tell the story of La Coupole’s role in the history of 20th-century art.”

François Bullier, a former employee of the Bal de la Grande Chaumière, situated at 120 Bd. du Montparnasse, transformed an old dance hall into what would become a truly celebrated hotspot for students and artists. Inaugurated on May 9, 1847 at 31 avenue de l'Observatoire, it underwent numerous transformations in function and name: initially, the "Closerie des Lilas” because of its 1000 lilac trees, then the "Jardin Bullier," "Bal Bullier," and "Le Bullier." It ceased all activities around 1940.

Throughout its evolutions, the Bullier had a dancing hall, gardens with swings and games, billiard tables, a bowling alley, and a shooting gallery: "la bonne société s’y amuse en journée, les étudiants y viennent rencontrer l’amour ou se saouler le soir venu, et les artistes s’y réunissent, à n’importe quelle heure du jour ou de la nuit, pour refaire le monde" (bmlisieux.com). It seems to have attracted a wilder crowd in the 1920s, when it functioned mainly as a music hall devoted to dances popular at the time. Artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay regularly attended the evening festivities, incorporating into their dance attire the notion of simultaneous contrast that they had developed in their painting.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, dancing was an important aspect of life in Montparnasse. At night, people sang and danced in cabarets, clubs, and street balls. The neighborhood vibrated with the sounds of music: waltzes, jazz mazurkas, tangos, polkas, all the world's rhythms found meaning in bohemian as well as highbrow nightlife.

In the early 1920s, one ball was especially noteworthy:

Grand Bal des Artistes, or Grand Bal Travesti Transmental (February 23, 1923). A philanthropic venture for the Union of Russian Artists, this ball was mainly advertised by Larionov and Goncharova, who designed the flyers, tickets, and poster. Other artists joined their efforts by contributing lithographs (Picasso, Juan Gris, Ferat, Derain, Goncharova) and poetry (Tzara, Soupault, Reverdy, and Cowley) for the 16-page program booklet.

There were four dance bands and two bars serving "pommes frites anglaises et cocktails." Among the 40 pavilions where artisanal goods were sold to raise money for the Union (Bowlt 1991, 82), were stalls featuring:

- Goncharova and her boutique of masks

- Delaunay and his Transatlantic Company of Pickpockets

- Larionov and his Rayonism

- Leger and his orchestra decor

- Cliazde [Ilia Zdanevich] and his 41-degree fevers

- Survage

- Bart

- Albert Gleizes

- Juan Gris

- Picasso

Larionov and Goncharova also designed the publicity materials for the The Bal Banal (March 14, 1924) and the Bal Olympique (poster, program, and tickets), or Vrai Bal Sportif (July 11, 1924), as well as the Grand Ourse Bal (May 8, 1925).

The Club and Montparnasse

Whether the women at 4 rue de Chevreuse actively participated in the alluring Montparnasse nightlife is unknown, but they certainly basked in its avant-garde context. Writers and students benefited from a staggering array of social haunts in the neighborhood. Like it or not, the University Women's Club was right in the heart of bohemia, and it offered Club residents an unparalleled window into the seedy glamor of their expatriate counterparts.

Abbé Ernest Dimnet, longtime friend and neighbor of Reid Hall, who published the very popular self-help book, The Art of Thinking (1928), wrote an article for The New York Herald Tribune in which he contrasted the debauched culture of Montparnasse with the calm seclusion of Reid Hall:

As a matter of fact, American women are happier in so-called Bohemian Paris than their more unbridled brothers, because decency is necessary to every declaration of independence, and if you spend all your freedom in licentious rioting there is nothing left to be spent. I suspect that the college girls in Reid Hall secure the maximum enjoyment from being so near the Dome and the Rotonde while all the time preening their wings in their coy rue de Chevreuse.

Despite the comfort and security afforded by the Club, many American women eschewed its cloistered atmosphere. A 1926 article in The Baltimore Sun mentions the substantial population of young women who opted for a more independent lifestyle. The article describes "hundreds of girls living 'independently' in their mansard garrets." Author Sterling Heilig interviewed one such young woman, asking if she didn't find the prospect of going broke in Paris "sordid." The unnamed young woman replied: "'Such risks are stimulating to the artiste [...]. A Paris garret does not scare me,' she bridled. 'Students and attics go together. It is the everyday commonplace that throws cold water on the artiste'" (July 11, 1926). One wonders if those young women truly moved in circles as wild as Kiki’s or if their choices of lodging and seemingly carefree attitudes were mere affectation.

Consult the sources for the neighborhood of the University Women's Club.