Mary Boyle, 1881 – 1974

Mary Elizabeth Boyle was born on August 11, 1881 near Crieff, Perthshire, Scotland, into an affluent family. Her mother, Agnes Lumbsden Boyle, died while giving birth to her third daughter. Mary, her two sisters, and two brothers then lost their father, Rear-Admiral R.H. Boyle, in 1892.

Her life in Scotland, France, Italy, and Spain was best described by Alan Saville who pieced together various accounts into a coherent trajectory (2016).

At the age of 18, Mary travelled to Italy to study art for two years before returning to Scotland and remaining there for the duration of WWI. During the war, she served as a nurse in a Belgian refugee center in Glasgow and made trips to both France and Italy. In 1919, she began studying French literature at the University of Grenoble.

Early on, Mary wrote poetry. Her WWI poems were published in Aftermath: Poems (Heffer, Cambridge, 1914) and Pilate in Exile at Vienne (Heffer, Cambridge, 1915). The first, composed of thirty sonnets, was dedicated to the memory of her brother, David Erskine Boyle, a professional soldier who was killed in 1914 near Cambrai. In 1922, she also published a book of children's poems, entitled Daisies and Apple Trees.

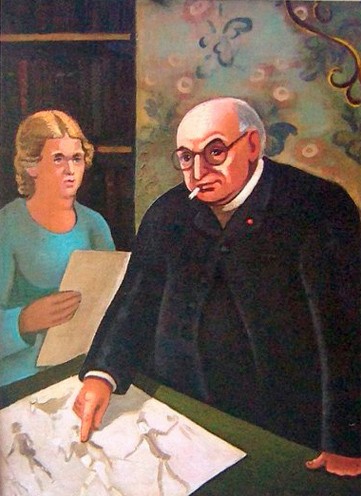

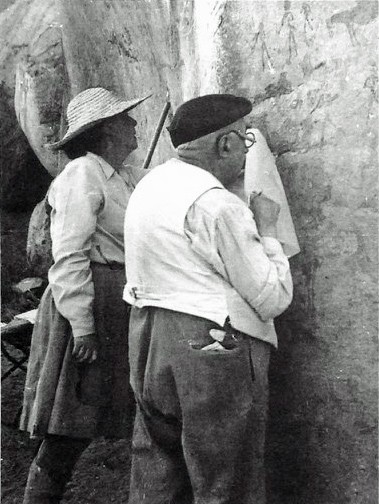

Boyle's interest in European prehistory began when she worked as secretary to the British scholar, Miles Crawford Burkitt, who had studied archaeology under Abbé Henri Breuil. Cave art became her lifelong passion when Boyle met Breuil in 1920. He was to receive an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University and stayed with the Burkitt family. According to Saville, when Breuil met Boyle, he invited her to become his assistant, saying she could learn much more from the master than from the student (Burkitt). They became collaborators for the last thirty-seven years of Breuil's life. He recognized that his work greatly benefited from her presence by his side: "[It was] greatly simplified thanks to the constant presence of my collaborator, Miss M.E. Boyle, who followed me everywhere, as my interpreter, negotiator, and assistant in my surveys" (translated from the French, 1957, 491).

In her poster presentation on "Women Pioneers in Rock Art Research," Reena Perschke summarizes Boyle's contribution to Breuil's work:

Together, they visited the rich cave art regions of Spain and the Dordogne as well as the parietal art regions of Africa. Mary Boyle didn’t just copy the paintings, but was rather elaborately involved in the discovery of new drawings and in their interpretation. The individual drawings of the petroglyphs were not always tagged with signatures. Therefore, the stock of the travels to Africa is stored in a collective "Fonds Breuil-Boyle" of the Bibliothèque centrale du Muséum national d´histoire naturelle in Paris.

Like so many women of the twentieth century, Boyle was not fully recognized in her own right, nor was she even credited as the crucial collaborator in Breuil's research and fieldwork. Yet, as Perschke rightly remarks:

By translating some French monographs from Breuil into English, she influenced seriously the correlation of technical and archaeological terms. Today, the technically competent translations, the contemporary elaborate monographs as well as hundreds of coloured petro glyph drawings of Mary Boyle remain and belong to the basics of archaeological petro glyph research.

In addition to her translations and the hundreds of petroglyph drawings she made in color, Boyle wrote monographs that were fundamental to research in prehistory. In 1924, she published Man before History, which, apparently, sold well on both sides side of the Atlantic and was used in the U.S. by the Parents' National Educational Union (1937). She also published a book on the Barma Grande cave near Ventimiglia, Italy in 1925, and a rather dense book on the history of cave art, In Search of our Ancestors, in 1927. She studied at the University of Madrid with Hugo Obermaier in 1931, and translated his work with Henri Breuil on the Altamira cave into English, in 1935.

Breuil and Boyle were assigned to the Archaeological Survey of the Union of South Africa in Johannesburg from 1941 to 1945, but it was only when they returned between 1947 and 1951 that they surveyed the caves in the Brandenberg mountain range of Namibia (Barnard 49). Their work led to several collaborative publications, including the controversial book, The White Lady of the Brandenberg (1955). In this book, Boyle developed her theory, to which Breuil adhered, that the figure represented a "white lady," probably a version of Isis of Cretan origin. The text generated a wave of hypotheses on the origin and dating of these cave drawings, and the Mediterranean influences suggested by Breuil and Boyle have since been dismissed. To crown all critiques, the figure identified as a "white lady" is neither a lady nor white.

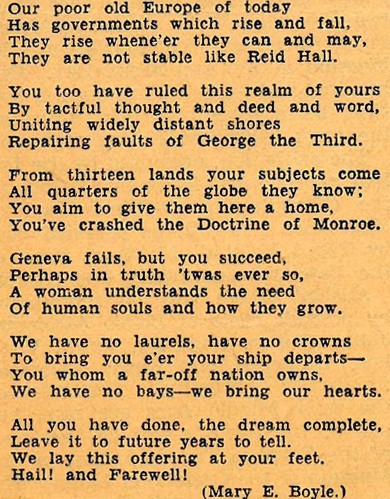

It is difficult to determine how long Boyle lived at the University Women's Club, though she clearly was a resident in 1936 when Dorothy Leet mentioned her work in a report to Virginia Gildersleeve: "She was making a study of prehistoric ruins (25,000 B.C.) as found near Les Eyzies" (Nov. 10, 1936, Barnard archives). Boyle was also among the Club residents who attended Leet's goodbye party in 1938. Her poetic tribute to Leet figured among the many presents and tributes made that evening, and was reproduced in the Herald Tribune (date). Boyle's colleague, Suzanne Cassou-de-Saint-Mathurin, a former resident of the University Women's Club, also participated in the festivities. After World War II, Boyle attended events at 4 rue de Chevreuse well into the 1950s and Breuil was invited to give talks on parietal art at the Club in 1955 and 1956.

Mary Boyle never married nor had children. When Breuil passed away, Boyle and the philosopher Claude Cuénot were his estate executors. The majority of Breuil and Boyle's papers were deposited at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. When Boyle died in 1974, all remaining documents in her possession were deposited at the Musée des Antiquités nationales (MAN) in Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Richard 28).

Sources

- Barnard, Alan. Anthropology and the Bushman. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Boyle, Mary, et al. “Recollections of the Abbé Breuil”. Antiquity, vol. 37, no. 145, March 1963, pp. 12-18. CambridgeCore.

- Breuil, H., M. E. Boyle, and E. R. Scherz. The Rock Paintings of Southern Africa. vol. 1, The White Lady of the Brandberg. Paris: Trianon Press, 1955.

- Breuil, H., M. E. Boyle, E. R. Scherz et R. G. Strey. The Rock Paintings of Southern Africa. vol. 2. Philipp Cave. London: Abbé Breuil, 1957.

- Breuil, Abbé Henri and Hugo Obermaier. The Cave of Altamira at Santillana del Mar, Spain. Foreword by the Duke of Berwick and Alba. English text by Mary E. Boyle. Madrid: Tipgrafia de Archivos, 1935.

- Breuil, Abbé Henri. "Réponse de M. l'Abbé Henri Breuil, membre de l'Institut." Bulletin de la Société de Préhistoire française, vol. 54, 1957, pp. 488-492.

- Diaz-Andreu, Margarita, "Les théories voyageuses: l’accueil britannique réservé aux connaissances sur le Paléolithique nées en France au cours de la première moitié du xxe siècle." Pour une Histoire de l'Archéologie XVIIIe siècle - 1945: Hommage de ses collègues et amis à Eve Gran-Aymerich, edited by Annick Fenet and Natacha Lubtchansky. Pessac: Ausonius Publications, 2015, pp. 281-299.

- Hurel, Arnaud. L'Abbé Breuil: Un préhistorien dans le siècle. Paris: CNRS, 2011.

- Le Quellec, Jean-Loïc. "Breuil et la 'Dame Blanche': naissance et postérité d'un mythe." Sur les chemins de la préhistoire: l'Abbé Breuil du Périgord à l'Afrique du Sud. Paris: Somogy, 2006, pp. 118-127.

- “Miss Mary E. Boyle (1881-1974)”, The Times, January 3, 1975, p. 12.

- Mora-Figueroa, L. D. (1974-1975) : “Miss Mary E. Boyle (1881-1974),” Ampurias, vol. 36-37, pp. 319-321.

- Perschke, Reena. "Women Pioneers in Rock Art Research: Mary E. Boyle, Erika Trautmann and Vera C. C. Collum." Twentieth International Rock Art Congress, IFRAO 2018 Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici. 2018. Poster.

- Richard, Nathalie. "Une recherche collective en cours: le programme 'Archives Breuil':

- entre préhistoire européenne et africanisme, un univers intellectuel et institutionnel au XXe siècle." Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 26-33.

- Saville, Alan (2016) "Mary Boyle (1881-1974): the Abbé Breuil’s faithful fellow-worker."Ancient lives: object, people and place in early Scotland. Essays for David V Clarke on his 70th birthday. Leiden, Netherlands: Sidestone Press, pp. 127-150.