Keller Institute, 1834 – 1890

Following the closure of Maisonabe’s orthopedic center at 4 rue de Chevreuse, Protestant pastor Jean-Jacques Keller and lawyer Valdemar Monod purchased the property and opened an international boarding school for boys, the first of its kind in France.

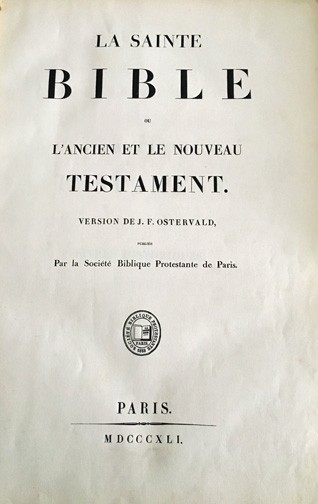

From around 1818 to 1850, a spiritual awakening ("réveil religieux") was promoted by Swiss and British preachers across Protestant churches in Paris. Keller, originally from Zurich, was among the Protestant clerics who traveled to Paris in August 1830 hoping to secure a teaching position in a religious establishment. He came into contact with several members of the "réveil" through whom he found a job as teacher and assistant director of the Collège Sainte-Barbe-des-Champs in Fontenay-aux-Roses, outside of Paris. Keller was charged with the instruction of its Protestant pupils, an experience that inspired him to establish a "maison d'éducation protestante."

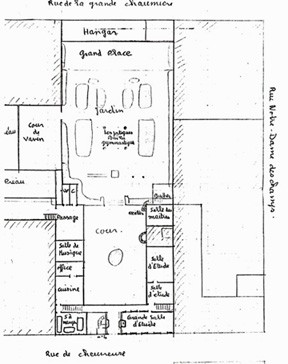

He partnered with Valdemar Monod (son of the pastor Jean Monod, President of the Consistoire Réformé de Paris) to acquire the property at 4 rue de Chevreuse. Archival documents at Reid Hall indicate that they retained most of the gymnastic equipment and orthopedic apparatuses from Maisonabe’s center, likely for use in physical education courses.

The school opened in 1834 with Monod serving as its first director, Keller as the main teacher, and Monod's sister managing the dormitory. Named Institution Keller after its co-founder, this rigidly Calvinist school focused on intellectual, moral, and spiritual teaching. In describing the early years of the Institution, Keller said, "Our ideal, which we perhaps followed with more zeal than wisdom, was the evangelization of our pupils" (as quoted in Mackay 266). The school grew rapidly, with close to 60 students enrolled by 1838 (Goulet 243).

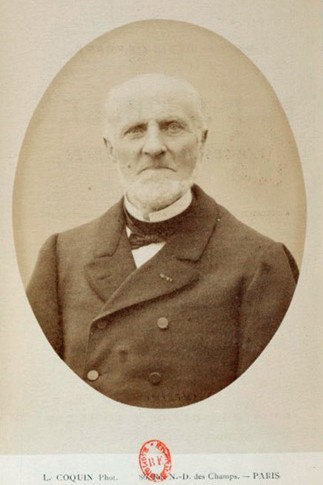

When Monod left the Institution Keller in 1836 to become a maritime insurance broker in Paris, the school was entrusted to Keller, who led it until his death on August 10, 1889. With the help of his son and daughter-in-law, Keller educated the children of well-to-do Protestants from many parts of the world for nearly 60 years.

In 1866, Keller also opened a day school called the "École industrielle" at 12 rue Vavin, which prepared young men for specialized training in business. The day school was later integrated into the facility on rue de Chevreuse.

An 1876 guide to Protestant Paris lists the Institution Keller as a school for French and English families whose sons follow the curriculum of the lycée Saint-Louis. Tuition ranged from 1,500 to 1,800 francs per year (Decoppet 379).

Keller's grandson, Gustave (1874 - 1954), remembers living and studying at the school as a child. In his memoirs, preserved in the Reid Hall archives, Gustave vividly describes life on the rue de Chevreuse in the 1880s:

[...] an ugly little street that linked the boulevard Montparnasse to the rue Notre-Dame des Champs… not one bit aristocratic, despite the name of this poor street: A few houses with housing for workers or 'petits bourgeois' and facing n° 4, two wine merchants on the ground floor. The remaining buildings were rather seedy furnished hotels. At the corner of the rue Notre-Dame des Champs there was another wine merchant whose house extended into the street, which caused the most unbearable kinds of bottleneck. Everyone signed a petition to expel this wine merchant. He was forced to align his house with the street, which meant that he couldn’t do important repairs, and so, it became a real ruin… a ruin that had no poetic charm (translated from French).

Gustave also recalled the boys' daily schedules and activities:

- 6h00 Wake up

- 6h30 Study hall

- 7h00 – 7h20 Religious service

- 7h30 Breakfast

- 7h45 Older boys went to the lycée Saint-Louis on Bd. St. Michel while the younger boys stayed behind for recess.

- 8h00 In-house courses taught by Gustave’s father and other tutors

- 12h00 Lunch

- 14h00 Classes resumed

- 17h00 – 18h30 Study hall

- 18h30 – 19h00 Dinner

- 19h00 – 19h30 Recess

- 19h30 – 20h30 Study hall, followed by a religious service and bedtime; the older boys could stay up until 22h00.

On Sundays, the boys slept until 7h00, had breakfast, went to study hall, and then to the Chapelle Taitbout on rue de Provence. In later years, they went to the Chapelle du Luxembourg on rue Madame. After mass, there was another study hall, where students were asked to write summaries of the morning's sermon, followed by a walk.

Gustave Keller also described the garden of his childhood:

For Paris, it was a beautiful and large garden. We reached it through the courtyard, by going down a few steps between the two stone pillars with their wrought iron gate. Right in front, there was the outdoor gym, or rather the springboard of the trapeze, which was suspended from a very large crossbeam laying on four large wooden poles, six to seven meters high. Above there was a platform so we could attach the trapeze on the side of the courtyard. We could also attach a second trapeze on the opposite side… [there also were] parallel bars and fixed bars (translated from the French).

More than half of the students at the Institution Keller were international, from England, the United States, Germany, Switzerland, and as far as Australia, Tahiti, China, and the East and West Indies (see Mackay; Keller and Bungener). Ten members of the Monod family studied at the school between 1834 and 1874, all of whom went on to university or religious careers. Many alumni became notable players on the world stage, like William Henry Waddington, French ambassador to England in the 1880s (the fourth student to register in 1834, remaining at the school until 1840); Edmond de Pressensé, religious essayist and member of the French National Assembly; and Albert Kaempfen, director of the École des Beaux-Arts (1882). In 1865, "Charles King, President of Columbia College from 1849 to 1864, brought his son to Paris and enrolled him in the Keller Institute. Young Charles, whose grandfather was the distinguished American statesman, Rufus King, stayed at the school for three years while his family toured Europe" (Davenport 28-29). André Gide, Nobel Prize-winner for literature in 1947, did not board at the school but was tutored by Keller's son, Jean-Jacques Édouard, between 1885 and 1887. Gide received excellent training during the eighteen months he spent with "Monsieur Jacob" and wrote about the "Pension Keller" in chapter 7 of Si le grain ne meurt. In Les faux monnayeurs, Jean-Jacques Keller figures as D'Azaïs.

During the Franco-Prussian war (1870 – 1871), the school was temporarily converted into an improvised field hospital (Goulet 245), one of the many "ambulances" supported by "religious orders, municipal authorities, companies, rich philanthropists…, Jewish, Protestant…, and Freemasons’ organizations, or even individuals” (Taithe 171, cited in Seltzer 8).

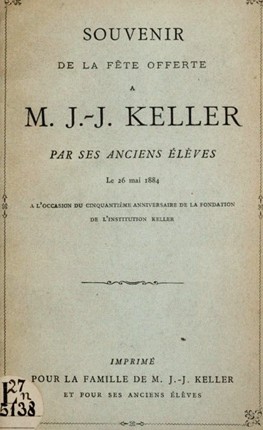

In honor of the school's 50th anniversary in 1884, Keller's former students hosted a fête celebrating their founder and his legacy. Waddington, leveraging his political connections in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, arranged for Keller to receive the Croix de Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur at the banquet, a surprise that Keller discovered when he unfolded his napkin.

Jean-Jacques Keller died at 4 rue de Chevreuse in August 1889. His son, Jean-Jacques Édouard ("Jacob"), continued operating the school for a few years but enrollments diminished, especially after the opening of the École Alsacienne in 1874. In 1892, he leased a plot of land in the back garden to Rev. Dr. Morgan of the Church of the Holy Trinity (consecrated as the American Cathedral in 1923). On behalf of Holy Trinity, a Protestant pastor in Montparnasse, Rev. William Newell, established St. Luke's Chapel on this plot. Keller rented the rest of 4 rue de Chevreuse to Elisabeth Mills Reid in 1893. Two decades later, she would purchase the entire property, including the site of the chapel.

Gustave Keller, quoted by Goulet, described his father's decision to rent out the property in 1893:

[...] for months, he struggled, trying to remain afloat, and finally he received an offer to rent the entire house for a project [to house] young American women who had come to Paris to study the arts, and he made a decision, in agreement with Aunt Eugénie Antonin, to rent the house. We thus left the rue de Chevreuse in August 1893, several weeks before I was admitted to the école Centrale (246).

Many years later, in 1929, Gustave Keller revisited 4 rue de Chevreuse. His reminiscences were recounted in a 1931 article for The South Atlantic Quarterly by Dorothy Louise Mackay, a European Fellow of the American Association of University Women at Reid Hall:

He regretted that his mother was unable to accompany him, for she had come to the house as a bride in 1869, and would have enjoyed seeing it again. She had recently cooperated with him in supplying much of the information concerning the history of the school used by the present writer. Monsieur Keller recalled that there had been few changes in the aspect of the house since his boyhood days. The well, he said, had been filled up ever since he could remember, and he had never investigated the passage on the other side. He pointed out the present office of the French Federation as the study of the masters in the Pension Keller. He examined carefully the old stone trough across the court. Its original purpose was as obscure then as it is now, but the schoolboys had used it for scrubbing ink off their hands, since its rough surface had proven a good substitute for pumice stone. The bell above the trough reminded him vividly of the daily routine of the school. He pointed out the old dining-room, behind the present loge, and the big study-hall across from it on the other side of the entrance. The Keller family had had rooms across the front, opening off the balcony (269-270).

Sources

- Davenport, William W. An old house in Paris: The story of Reid Hall, 4 rue de Chevreuse, Paris VI. France: Reid Hall, Inc., 1970.

- Decoppet, Auguste Louis. Paris protestant: ses églises, ses pasteurs... Paris: J. Bonhoure, 1876. HathiTrust.

- Faure, Denis. “Valdemar Monod, un fondateur de l’Institution Keller et sa famille.” Cahiers du Centre de généalogie protestante, vol. 153, January-March 2021, pp. 25-31.

- Goulet, Alain. "Sur les traces du Réveil." Bulletin des Amis d'André Gide, vol. 39, no. 170, 2011, pp. 235-246. JSTOR.

- “Institution Keller.” Advertisement. Journal des débats politiques, September 17, 1866, n.p. RetroNews.

- Keller, Franck. “L’Institution Keller: 1834-1893 du 4 rue de Chevreuse (Paris VIe).” Cahiers du Centre de généalogie protestante, vol. 152, October-December 2020, pp. 194-223.

- Keller, Franck and Eric Bungener. “Notices biographiques d’élèves de l’Institution Keller,” Cahiers du Centre de généalogie protestante, vol. 153, January-March 2021, pp. 32-51.

- Keller, Gustave. “Extrait de ‘Souvenir de Famille,’ 2 cahiers rédigés durant la première guerre à l’intention de ses enfants.” Manuscript given to Reid Hall archives in 1993 by Franck Keller.

- Mackay, Dorothy Louise. "Reid Hall, A Relic of Old Paris." South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, July, 1931, pp. 260-271.

- “Notice Biographique: Jean-Jacques Keller.” Manuscript, Reid Hall archives.

- Seltzer, Greg, "The American Ambulance in Paris, 1870-1871," Madison Historical Review, vol. 6, article 3, pp. 1-22. JMU Scholarly Commons.

- Souvenir de la fête offerte à J.-J. Keller par ses anciens élèves, le 26 mai 1884. Paris: C. Unsinger, 1884. Gallica.