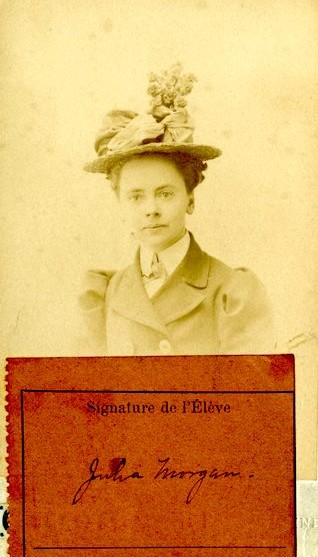

Julia Morgan, 1872 – 1957

An acclaimed architect in her lifetime, Julia Morgan, like so many women, has been largely overlooked in the historical record. The first comprehensive biography devoted to Morgan was not written until 1988, when architectural historian Sara Holmes Boutelle, art and architecture teacher at the Brearley School in Manhattan, published Julia Morgan, Architect. Deeply researched and filled with Morgan's drawings and photos, this pioneering biography won the California Book Award Silver Medal in 1989 and catalyzed further interest in Julia Morgan: other biographies (e.g. Kastner, McNeil) and numerous articles have critically examined her contributions to the history of American architecture.

In this profile, we simply wish to highlight Morgan's presence at the American Girls’ Art Club in Paris, where she met other determined and defiant women; this experience paved the way for her future successes in France. The "American Club provided a safe, welcoming, and studious atmosphere, if not a luxurious one, as well as instant companionship that enabled Morgan to transition smoothly into life in this international metropolis" (McNeil 88).

Born in San Francisco on January 20, 1872, Julia Morgan was the daughter of Charles Bill Morgan, a mining engineer from New England, and Eliza Woodland Parmelee. After earning a B.S. with honors in civil engineering at the University of California Berkeley in 1894, Julia entered Bernard Ralph Maybeck’s architecture atelier. At his urging, she left to study in Paris, since the famed École des Beaux-Arts began accepting women in 1897.

Morgan traveled to France with a friend, Jessica Peixotto, who planned to study social sciences at the Sorbonne, and her 19-year-old cousin, Nina Thornton, who would spend the next four months studying art.

Morgan lived at the Girls’ Art Club for a year beginning in June 1896, and remained in Paris another five years. In her letters, she described some of the amenities available to Club residents. To the LeBruns, she wrote:

The service might be a trifle more dainty, the rooms have a more convenient assortment of furniture .... But to make up for little failing of these natures [sicl, it's a perfectly safe and proper place, [and] the garden ... is large and very pleasant, when you get used to it (cited in Katzner 855).

To a sorority friend, she described her bedroom:

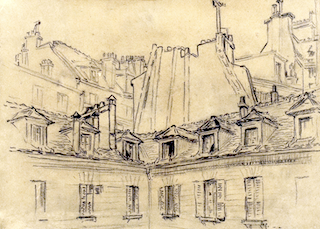

I like mine because it's quite large and has plenty of fresh air, but it's not elegant in its furnishings. The narrow dark halls have most mysterious and unexpected steps. You get to know where they come and do it mechanically – but at first! They have the hexagonal tile floors all the old houses had, and many of the newer ones too. I always wanted a room with them, but those who have say they are very cold. We have funny little stoves too, like lard cans set up on three little legs. Very active little creatures which heat up most alarmingly. But the chiefest (sic) treasure is our Fauchette-our little maid. Would not you picture the name as belonging to a dainty little creature in cap and apron? Well our Fauchette has a white cap – but it rests on an iron rust-colored wig –which in turn covers a tiny weazened face, with many wrinkles, pale blue eves, one single tooth at a most peculiar angle in the lower jaw – and a voice ... whose nasal shrillness I have never heard the like of – and whose idea of cleaning is not remarkable (cited in Katzner 855-856).

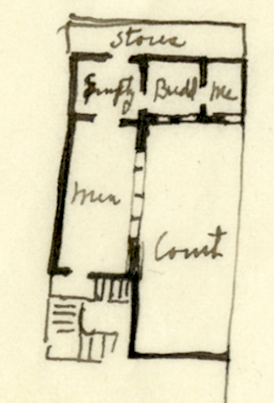

Morgan first worked with the young architect Marcel Pérouse de Monclos, who had graduated from the Beaux-Arts in 1893 and opened a small studio to prepare students in architecture. He had six pupils, 3 men and 3 women: Julia Morgan, Fay Kellogg (who left before Morgan arrived) and Katharine Cotheal Budd, who left after six months and would later become the first woman architect admitted to the New York Chapter of the AIA in 1924. Despite the tight quarters in the studio and the unfriendly atmosphere generated by the resentful male students, Morgan vowed to stay until “[I can] find out in the meantime whom I could have better” (Kastner 873). Years later, Kellogg, Budd, and Morgan collaborated on designing Hostess Houses for the YMCA (c. 1917 – 1918).

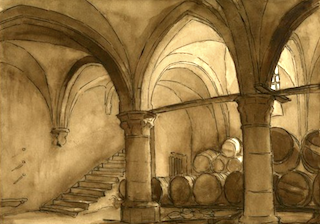

Aside from her work in the studio, Morgan also audited classes at the Beaux-Arts – the only option for women in the hallowed, male-dominated institution. She tired of the adversarial nature of the Beaux-Arts and enrolled at the Académie Colarossi, located just around the corner from the Girls' Art Club Club, where women formed a majority. She studied drawing and sculpture with Jean-Antonin Injalbert.

Morgan left the Girls’ Club in 1897 and its “measly little street with a two foot sidewalk” (cited in McNeil 88). Several apartments later, she found one below that of the Maybecks, one block away from place St. Sulpice at 7 rue Honoré Chevalier. Her roommate was sculptor and Club resident Sara Whitney, a student of Rodin who showed great promise but discontinued her art career after marrying artist Boardman Robinson in 1903.

Time was of the essence since Julia was already 25 years old and the Beaux-Arts required that its students to graduate before they turned 30. Several prominent figures wrote letters of recommendation supporting Julia’s admission to the June 1897 entrance exams: the ambassador of the United States to France; Will S. Aldrich, Secretary to the American Architecture School in Rome; Bernard Ralph Maybeck; de Monclos; and Chaussemiche. Julia was finally admitted to the exam in October 1897 but she did not pass. After another failed attempt in April 1898, she finally passed the exam in October 1898, and was admitted to the “Seconde Classe” in the architecture section of the Beaux-Arts on November 7, 1898 (“Feuille de renseignements, section d'architecture”). Several California newspapers noted her accomplishment:

Julia Morgan […] has just successfully passed the entrance examinations for the École des Beaux Arts, department of architecture. The honor is all the more marked that Miss Morgan is the first woman to be admitted to this special department (“California Girl Wins High Honors”).

Her achievement was in passing successfully the entrance examinations to the École des Beaux-Arts, and immensely difficult task for a Frenchman, but a staggering feat for an American on account of the many purely technical words which must be mastered (“Miss Morgan’s Success”).

Julia’s brother Avery came to Paris in October 1898 in the hopes of also enrolling at the Beaux-Arts. Though he was never admitted, he worked in the atelier of famed architect Victor Laloux, who designed the Orsay train station, from 1898 to 1900. Avery and Julia moved into an apartment close to the Beaux-Arts. Around the same time, the Atelier Monclos was disbanded and Morgan began working with architect-instructor François-Benjamin Chaussemiche, winner of the Grand Prix de Rome, to whom she had been introduced by Maybeck. She continued working with Chaussemiche even after her admission to the Beaux-Arts, gaining practical experience along with her academic studies – this was no small task as the assignments at the École were seriously demanding. Morgan designed a ceremonial salon for Harriet Travers Fearing’s home in Fontainebleau with Chaussemiche (Leconte; Clausen; McNeil).

Julia successfully completed her studies at the Beaux-Arts in 1901, one month shy of her thirtieth birthday. In February 1902, she earned the “certificat”, becoming the first woman to graduate in architecture. French newspapers hailed her accomplishments, albeit with a touch of irony:

When the decision was made four years ago to admit women to the School, we were far from thinking that they would enroll in anything other than painting or sculpture. This was without considering America, from where the unexpected so often comes to us. So, a charming young girl from San Francisco, Miss Julia Morgan, showed up with blueprints under her arm and a set square in hand, and we thus had to teach her how to build palaces. She excels at it today, and a few days ago Miss Morgan became the laureate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts in the architecture section.

Chaussemiche was interviewed by writer and journalist Marie-Louise Néron (pen name of Marie-Louise Génault) from the French feminist newspaper La Fronde. Launched on December 9, 1897 by actress, journalist, and activist Marguerite Durand (1864 –1936), this daily was the first of its kind in France, run and written entirely by women. The interview is transcribed in full below since it clearly demonstrates Chaussemiche’s unwavering support for Morgan (translated from French):

When the École des Beaux-Arts decided to open its doors to women, after a campaign in which La Fronde played an important role, the École expected to welcome in its workshops only young women who wished to become painters or sculptors. But now the architecture section has women students too. A few days ago, one of them, Miss Julia Morgan, achieved brilliant success. Miss Morgan is American, her family lives in San Francisco. Highly educated, with a pronounced taste for the art of building palaces, Miss Morgan came to Paris four years ago and competed in the entrance examination to the École des Beaux-Arts, where she had been preceded by other American women, less well gifted, no doubt, since after a few months they gave up their studies, which they found too arduous.

Miss Morgan failed the entrance exam for the first time. But she courageously attended Mr. Chaussemiche's atelier, where she became one of his good students and where she continues to work outside the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

- What do I think of Miss Morgan?” Mr. Chaussemiche replied to me yesterday when I asked about the laureate of the architecture section, “In fact, I find her to have serious qualities. She will be a very good architect. From the point of view of design and invention, she demonstrates great ingenuity. Her taste needs to be refined in terms of ornamentation. Miss Morgan has this in common with her compatriots, she mixes genres a little too much, but this slight fault will quickly pass and I have no doubt that she will succeed very well in her country.”

- So, you would trust her with the job of raising a building?

“Absolutely. scientifically speaking, Miss Morgan is far superior to half of her male classmates. She has studied hard and passed all her school exams with flying colors.”

Mr Chaussemiche gave me a few details about Miss Morgan's recent compositions, and the exam in which she had to design a large vestibule for a palace building, and for which she would surely have won a prize, if she hadn't had the misfortune of being disqualified because of a sketch for which she didn't have time to provide a final copy.

“At any rate,” says Mr. Chaussemiche, “Miss Morgan plans on returning to her country soon.”

- Where she will work?

- Where she will work," my interlocutor underscores with a smile, “she even has work in the pipeline and is in demand in New York and San Francisco, but she will opt for the latter city, where she was born, where her family lives, and where the climate is much better. In America, she will be no exception. Wasn't it a woman who built the Women's Palace at the Buffalo Exhibition, and also a woman who supplied the plans for the one at the New York exhibition?”

Seeing Mr Chaussemiche so benevolent, I was going to write so feminist, it immediately occurred to me to ask his opinion on the entry of women into the rather special career of architecture.

“Of course,” he replies, "one might object that a woman cannot visit building sites, climb scaffolding to check on the work, and come into contact with more or less rude masons and carpenters. But an architect's duties do not consist exclusively of these rather unpleasant tasks. There is the all-important office work, the sketches, plans, etc., for which women are very well suited. As for me, if Miss Morgan were not working in San Francisco, I would gladly hire her, convinced that she would be of service to me.”

- Not all architects think that way.

“I know, opinions are more than divided. It's the eternal question of competition from women. All professions are terribly crowded, we have to admit, and if there are twenty competing for one job, the prospect of being twenty-five is frightening. This is no reason, however, not to grant women the right to work, which all intelligent beings have, according to their aptitudes and faculties.

The ideas put forward by Mr. Chaussemiche are too similar to my own for me to diminish their impact with more comments.

This is yet another opening in one of the careers that has hitherto been closed to us. The Americans were the first to show us the way: we can be sure that they will be followed, despite recriminations, ill will, and perhaps obstacles...

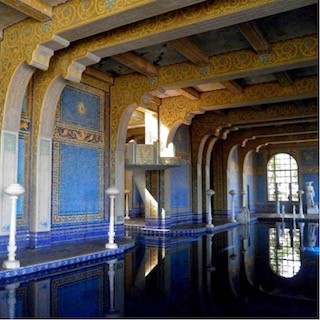

After graduating from the Beaux-Arts, Morgan continued working with Chaussemiche in France and Italy. She returned to California in July 1902 and joined the architectural practice of John Galen Howard. On March 1, 1904, she became the first woman licensed to practice architecture in California, and decided to establish her own studio, which yielded many successes: over a span of fifty some years, she completed more than 700 built projects. As her biographer Sara Holmes Boutelle observed, “Most of her important clients developed… from recommendations from former clients and a network of both women of wealth and women professionals of more modest economic means" (The Julia Morgan Papers at Cal Poly). Even her biggest client, William Randolph Hearst, came through a recommendation from his mother, whom Morgan had met in Paris at a gathering of American women. Julia Morgan spent more than 25 years designing and executing projects for Hearst, including the headquarters of the Los Angeles Examiner newspaper (1915) and his palatial San Simeon home (1919-1942).

Morgan, who never married, died at the age of 85 on February 2, 1957 in San Francisco.

The Julia Morgan Papers, some of which have been digitized in the Online Archives of California, contain architectural drawings and plans, office records, photographs, correspondence, project files, student work, family correspondence, and personal papers, which were given to California Polytechnic State University by her relatives in 1980.

Julia was posthumously honored for her extraordinary lifetime achievements with the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects in 2014. It is possible that her gender and her aversion to public recognition played a role in obscuring her legacy. “She steadfastly refused to enter competitions, write articles, submit photographs to architectural magazines, or serve on committees, dismissing such activities as fit only for ‘talking architects’” (Boutelle cited in Hawthorne). One wonders what she would make of the 21st century's interest in her work and architectural prowess.

Sources