Grace Gassette, 1871 – 1955

Grace Gassette was born on March 28, 1871 in Chicago, Illinois, the third child of Martha Graves Gassette and Norman Theodore Gassette, a real estate mogul, president of the Masonic Temple, and president of the Chicago White Stockings baseball team. Martha died when Grace was just two years old and Norman married her stepmother, Amelia Louisa Boggs, seven years later. Although official records list Norman Gassette as her father, Grace revealed in the 1938 book La Santé that her biological father (whom she declined to name) had died when she was six months old (39). Norman passed away when Grace was 20 years old, but he left an indelible mark on his daughter and influenced her future spiritual convictions (La Santé 40).

Grace and Amelia Gassette traveled to Paris in July 1896 in the company of Mrs. Charles Gilbert Wheeler, founding member of the Chicago Orphan Asylum (1849 – 1892), on whose board Amelia had served (“Personals”). Passport records indicate that Amelia stayed in France from 1896 to 1919. When she registered with the American Consulate in 1908, she noted that she was in Paris to make a "house" for her daughter, who was studying art. Though the two did live together and remained close for many years, Grace later reflected on their differences: "My mother [...] was afraid that the knowledge my father gave me would make me vain, and she did her utmost to make me feel inferior [...] it took me years to understand my mother's manipulations. And I struggled between my ‘EGO’ and my filial duties [...] (La Santé 40).

Grace and her stepmother lived in a beautiful apartment at 16 rue Boissonade, where they welcomed frequent visitors and hosted weekly Tuesday receptions for their American compatriots (“Mrs. French [...]”). The Gassettes moved in the artistic circles surrounding Gertrude Stein, Alice Woods Ullman, and Emily Dawson (Wineapple 314). Grace studied art under Mary Cassatt and took anatomy classes at the École de Médecine (Gibbons). Cassatt, however, was not convinced about her young pupil’s talent:

Another Chicago native, Grace Gassette, had the courage to approach Cassatt while she studied in Paris in 1906. Gassette spent many hours absorbing all she could of Cassatt's advice and opinions, and wrote a laudatory article on her for the Chicago Post. In later years, after having returned to the United States, Gassette would list Cassatt as her teacher in the catalogs of exhibitions she entered. Cassatt, for her part, was vastly amused by the young woman who had nerve enough to call not only on her but also on Degas, even though she did not believe that Gassette had the makings of an artist. She wrote candidly to Louisine Havemeyer that 'Art is not at all her affair, except to talk; she will never paint anything of account.' (Mathews 270).

In reality, Cassatt's judgment was even more severe:

I have a letter from [undeciphered] Gassette very grateful to you for having allowed her to see the collections; unfortunately she does not seem any nearer matrimony though the man has gone out to spend the holidays in Chicago with her intently - a Pity indeed, for art is not at all her affair, except to talk she will never paint anything of any account. How lives are wasted - (Cassatt letter to Louisine Havemeyer)

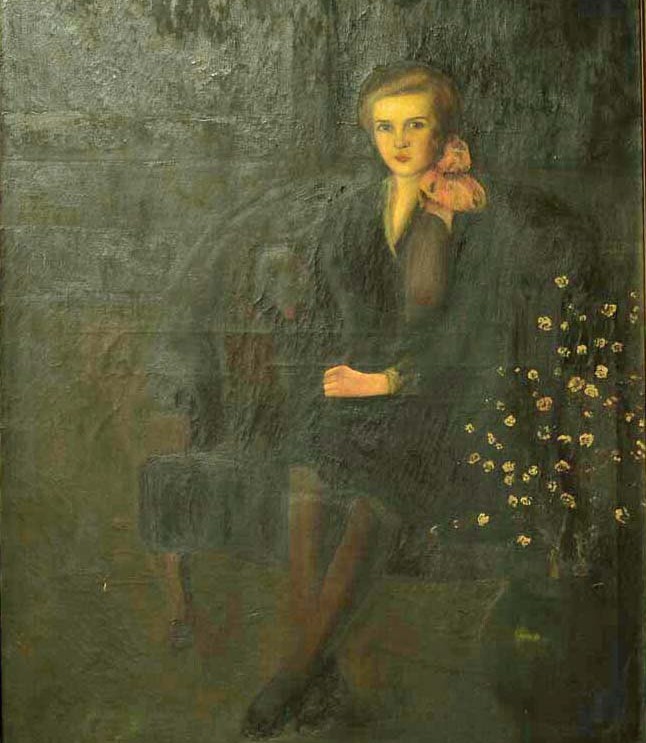

Cassatt's opinion notwithstanding, Gassette was a prominent exhibitor in the U.S. and Europe for nearly twenty years, earning critical acclaim as a portraitist and colorist:

With a depth and richness of colorings that are strikingly traditional, and in fascinating rhythm of temperament— thus Grace Gassette paints her pictures, whether landscapes, Interiors or in portraiture. When she uses intense colors she attunes them melodiously and never shrills into overstrain or into a discord. When she takes to minoring in hues she reflects the antique sweet mellowness that dominates in delicately shadowed old masterpieces. “I put into my paintings the results of years of study of the colorings on old masterpieces. I don't think we can improve on the traditional in our modern art (Webster 9).

As early as 1898, Grace showed a portrait of her stepmother ("Portrait de M.G.") at the Salon des artistes français (“Honor for a Chicago Girl”). She also exhibited at the Girls' Art Club in 1899 (a still life of yellow chrysanthemums in a vase against a blue background), and her work was accepted at the Salon des Beaux Arts several times:

- 1899, miniature portrait, "Miss Morris"

- 1901, two miniatures

- 1903, "Chez Mme Esté," portrait

- 1904, portrait of a woman in a blue dress

- 1909, "Portrait de la Baronne von S…"

- 1910, "Portrait de Mlle M.A. [Miss Aldrich]," "Intérieur hollandais"

In 1910, nine of Gassette's paintings were shown at the International Lyceum Club for Women Artists and Writers in France. Two of her paintings were shown at the Salon of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, including a portrait of Mildred Aldrich.

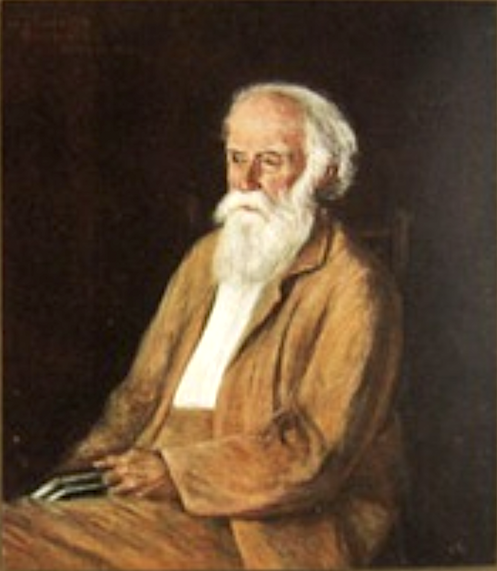

While Grace spent the majority of her life in Paris, she also made periodic visits to the U.S. to exhibit (e.g. shows at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh and Art Institute of Chicago) or execute portrait commissions (e.g. gallerist Albert Rouiller). She painted “[…] a special class of portraits like John Burroughs, the naturalist; Dr. Emlie O. Hirsch, the rabbi; Agnes Nestor, whom President Wilson appointed to the vocational schools commission; Gertrude Stein, who launched Matisse and the cubists; and typical Chicago worthies like Judge Landis, James Dr. L. L. McArthur and John McCutcheon” (Heilig 46). Her 1913 exhibition of 16 portraits at the Rouiller Gallery was favorably reviewed as “a powerful expression of a real personality” (“Works of Healey [...]”). Grace submitted her portrait of Gertrude Stein to the 1913 Armory Show in New York. It was accepted by the curator and even included in the catalog (number 148.5), but the painting was never actually shown at the exhibition. The curator eventually wrote Gassette a letter of apology (Martinez 103-104).

When WWI broke out, Grace was in Chicago. She returned to Paris in August 1914 to be with her stepmother, who was helping to prepare the emergency department of the American Hospital under the direction of Ambassador Herrick's wife (“What War is doing to Society Flittings”). When asked by a reporter how an artist took up this kind of work, Gassette responded:

I was in Chicago, where I was to have painted George W. Reynolds, president of the Commercial National Bank," she said. "When war was declared I quit New York, commissions and all. I arrived in Paris in mid August, glad to find mother tranquilly holding the fort in the flat. That night I wrote Dr. Gros, offering my services in any capacity. By return mail told me to come to the Lycee Pasteur. The building was almost ready, the beds were being carried in and a few nurses getting things in order. In the rooms the head operating nurse Miss Doane, set me to rolling bandages. I asked if she needed more help, and, as she said she did, I began looking for women outside (Heilig 46).

By September 1914, Grace had been put in charge of the surgical dressing department, which grew in size and importance:

We not only supply our own ambulance where we have 600 wounded, but we are able to send large quantities of supplies to our auxiliary hospitals. The development of this department is entirely due to Miss Grace Gassette of Chicago, who undertook its direction in September, just after the war broke out. [...] She now has more than 50 volunteer assistants at the hospital, and a large number who work at home making everything used by the surgeons. We have reached the 2,000,000 mark and at present have to turn out 7000 compresses, make 2000 cotton balls, roll 400 bandages and make 300 combines, besides 1000 fluffs a day, to keep up with our needs (Douglas).

Her work at the Ambulance brought her into contact with French surgeons desperately in need of additional support to treat the seriously wounded:

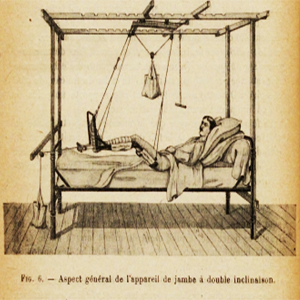

At intervals in her bandage-wrapping she came into the surgical wards. There she would find various surgeons and orderlies and what-not looking profound around the bed of a man whose leg had been broken in a way that had never been reduced to print. They didn’t know what to do with a leg like that. They usually wound up by putting it in one of the old-style apparatus. They knew perfectly well that it was not what the leg needed, but they could not invent anything better. [...] Now let us get back to Grace Gassette. She would look in at that suffering soldier and those puzzled surgeons and, by and by, her Yankee aptitude would get the better of her (Corey 11).

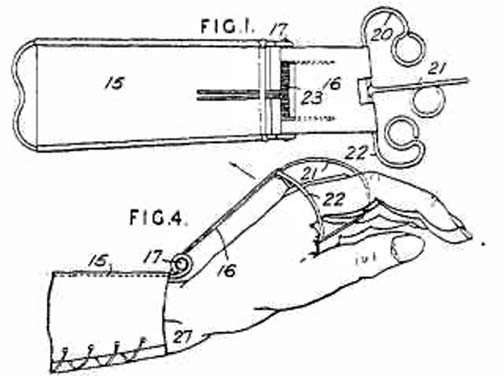

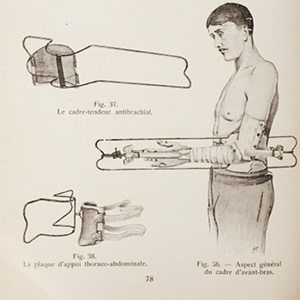

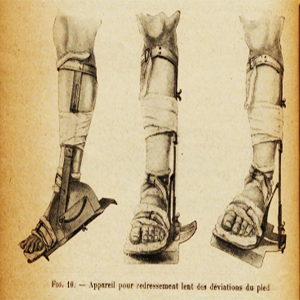

Gassette put her talent and ingenuity to good use by inventing orthopedic devices that surgeons could employ on their wounded patients. Doctors began to recognize her ability as a “deviser of splints” (“Notes: Apparatus for Fractures”) and called on her to fashion implements for fractured wrists, arms and fingers, and legs. In 1915, she described the breadth of her work to the Chicago Examiner:

I am in charge of the surgical dressing department. We prepare everything for the use of the surgical staff. I have fifty-five women working for me. We are all volunteers and have made 750,000 different things since the war began. This is a department that does not exist in any other hospital, for we make all the orthopedic things, too. How many of this kind that I have invented would seem like boasting to tell, suffice it to say that I am helping by doing what I can, and by economizing the materials and money that is given me for this work. It costs 37 centimes, or a little over 7 cents, a day per man for the surgical dressing; it is a veritable factory, and it seems strange for an artist to be so practical” (Dowager 50).

By 1917, Gassette and her colleagues had supplied 50 military hospitals with 6,000 devices (Stepansky 80).

In November 1917, she left the Neuilly hospital to serve as technical director of the "Comité Franco-Américain contre les impotences fonctionnelles," which assisted wounded soldiers in regaining the use of their limbs. With the support of Dr. Paul Reynier of the Académie de Médecine, she founded the Corrective Surgical Appliances Committee and opened a carpentry and smithing workshop in her atelier, located across from her apartment, at 17 rue Boissonade. Discharged French veterans manufactured her appliances in this workshop, a project which was subsidized by American donations (Reynier 410-411). Gassette boosted morale by opening her atelier to American soldiers, who played the piano, danced, and socialized with local women. She also established a “reeducative school" where wounded men could be “trained to continue in their old occupations.” They were guaranteed a living wage and received a 10% commission on the goods they manufactured and sold (Wilson 14).

Gassette treated soldiers in her atelier, fitting the men with splints for their wounds or shortening, tightening, and adjusting appliances as needed. When men were too ill to be moved, she traveled all over France to attend to these special cases. For her invaluable work with their soldiers, the 109th Infantry Regiment named her honorary corporal stretcher-bearer.

Over a brief period of time, Gassette devised and adapted over 200 types of orthopedic appliances, using elastic rubber and steel spring systems. Her apparatuses prevented amputations, repaired paralyzed limbs, relieved pain and pressure, and gave maximum comfort to soldiers with severed nerves (Gibbons 3). By May 1918, her workshop had manufactured over 30,000 pieces (Reynier 411).

Gassette’s inventions were recognized as a significant contribution to the war effort and she was decorated with the Legion of Honor on June 14, 1917 in Paris. She was the second American woman to become a "chevalier" during the war, after famed novelist Edith Wharton. Gassette's response to the honor was "I feel that the decoration was intended for Chicago, which has subscribed most of the money that has made the work possible. We use expensive quantities of leather, elastic, wood, and steel, and Chicago has paid the bill. Chicago deserves the credit" (Gibbons 3).

The fact that one previously untrained in orthopedics, with a knowledge of anatomy, plenty of horse sense, ingenuity, resourcefulness, and an earnest desire to serve humanity, should have obtained a reputation in this line, merely emphasizes the already well-known fact that medical men and surgeons at the front are not sufficiently trained in the use of appliances and do not realize their lack in this respect (Lowman 795).

Exhausted by so many months devoted to the war effort, Gassette returned to the U.S. in late 1918 for nearly five months of sick leave at the Pennoyer sanitarium in Kenosha, Wisconsin. A letter of support from Paul Reynier, President of the Comité Franco-Américain and member of the Académie de Médecine, enabled her to take this leave:

At this moment when you are leaving for your own country to take a well-merited rest, and which your health demands, allow me, as your President, who has seen you at work, to thank you in my name and in the name of all the wounded, American and French, for that which you have done for them. It is thanks to you and your activities, to technical direction, so lucid, that our work, unique in its kind and so useful, combating functional impotence which has followed the wounds of war, has taken such a great development. Thanks to you, that from our work-shops, have been issued to be distributed such a great number of ambulances, such a quantity of wooden frames, appliances for the treatment by suspension (called American) of fractures of war, which we have popularized for the great good of our wounded. It is also thanks to you that our work has been able to give to the hundreds of wounded healed of their wounds but still having mutilated members, paralysis, contractures, loss of substances, the appliances which have rendered their infirmities more supportable, diminishing them and permitting them once more to earn their livelihood. If all those you have thus helped, with no cost to them, could follow you in America and constitute your cortage, what an enormous advertisement there would be for our work, and by what an ovation you would be received, if they proclaimed [...] their grateful thanks to our work with which we credit the great American nation which has, since the beginning of hostilities, sustained us, never ceasing their interest in our wounded [...] (Letter to Gassette, November 6, 1918).

Amelia joined her stepdaughter in Kenosha in 1919, and later moved to Chicago, where she gave talks about her war work. She died at home in August 1920.

Grace Gassette returned to Paris in May 1919. In a letter published in the Kenosha News, she outlined her future plans in France:

I am now returning to France to study the after-war needs of the cripples who have been so dear to my heart. What these needs will be I can only tell after I have arrived in France [...] War cripples soon become civilian cripples, so I feel what we have learned in this great conflict should be applied to the civilian cripples indiscriminately regardless of how and when they became handicapped (“Seeks to Save Crippled Yanks”).

It is not clear if these plans ever came to fruition. She briefly resumed her career as an artist, showing a painting at the "Exposition d'Artistes de l'École Américaine" at the Musée du Luxembourg. No later works of art by Gassette are extant. Sometime in 1926, she moved out of Paris and bought a 14th century Benedictine convent, the Prieuré of Bazainville (Yvelines), where she lived until her permanent return to the United States many years later (Haynes).

For years Miss Gassette worked to restore the Priory to its old state. She organized the gardens, the park, cleared the primitive masonry and the old woodwork. Nothing was more evocative than the great hall with its fireplace of carved medallions, the severe kitchen, the small oratory paneled in polished and blond wood, the beamed staircase visible, each elbow of which bore the mark of the Matins' lamps and each step the wear and tear of the Benedictines' steps (translated from French, Barbarin 30)

Georges Barbarin, who met her in 1934, described an exceptional woman whom others viewed as a kind of formidable recluse, "la dame-ermite" (Boyé 239).

When I knew her, the 1929 American crash had completely ruined her. Of the twelve servants who previously served her, only one remained working as concierge, valet, cook and gardener, and Grace Gassette easily supported a poverty which seemed to her a blessing from heaven (translated from French, Barbarin 30).

Barbarin also claimed she was exhausted and half-blind from years of intense selfless devotion. A reporter for the Chicago Tribune visited her in July 1938 and was astounded by her appearance:

Since, as a youngster, I had seen Miss Gassette, she was changed from a large handsome woman in the prime of life, with black eyes and hair, to a small stooping figure, white haired and sad, almost a tragic muse. [...] Before the war she collected ancient furniture throughout France, and on her peregrinations found the lonely monastery. This she bought and has lived in it ever since. The cloister itself, although beautifully paneled, had no charm for me at all. I found it sad, damp, and dreary. But the garden, where monks had read their breviaries and told their beads under the yews in the long ailes for six centuries, had allure. Great rhododendrons bloomed there, and trees of rich, rare varieties, and the paths were padded with long dead leaves, so that one walked softly.” [...] Miss Gassette lives here alone and, as a result of much study and meditation, has become a mystic and a faith healer. Upon this subject she is writing a book as she passes her days far from the madding crowd. She has, however, friends and neighbors, among them Mme. Walska, who visits her in her solitude (“France Offers Varied Program for the Season”).

Gassette’s war experiences and poor health, combined with an early religious education, led her on a spiritual path heavily influenced by the tenets and beliefs of the Fillmores. She found in Barbarin the perfect person to carry forth some of her thinking, transforming him from a lighthearted poet and journalist into a devoted proponent of theosophical principles. She convinced him to translate the work of the much-critiqued British psychiatrist Alexander Cannon (L’Influence invisible), which introduced Barbarin to the world of hypnosis, the occult, and the paranormal. Gassette and Barbarin co-wrote a treatise on healing the body through thought, La Clé: "She was made to dominate, convince and instruct and her Priory became the meeting center whose base was La Clé" (translated from French, Barbarin 35). Gassette and Barbarin parted ways in 1935 but remained in touch even after she returned to America.

In 1938, Gassette wrote another self-help book on nutrition and the inextricable spiritual bond between mind and body, La Santé. Physique, mentale, spirituelle:

I hardly thought when I wrote La Santé that I would be guided towards a practical solution for physical Regeneration that so many others have sought. I might never have succeeded if I hadn't had my accidents. And yet the Bible tells us that we can renew our youth. When we delve deeper into this question, we feel that it is unacceptable for the body to deteriorate at the very moment we acquire a certain wisdom. It is for each of us to recover our lost powers, by putting order in our own temple. May the light illuminate the world before the arrival of the Prince of Peace so that everyone is ready and our lamps are on (translated from French, preface to 1950 reprint).

Gassette returned to the U.S around 1943. Her beloved Priory was severely damaged by the German occupation in WWII (“Miss Grace Gassette”).

Little is known about her later life in the U.S., other than her continued interest in healing practices, especially homeopathic salts, which she recommended as an unsuccessful remedy for dying President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 – 1945 (Ferrell 34). When she turned 80, she was living in New York and wrote a preface for the 1950 reprint of her book La Santé:

Even though I am American, after so many years in France, I found myself like a stranger in the United States, in a foreign Land. My country was unrecognizable, all human values had changed since my childhood. Furthermore, for the first time in my life, I discovered that I had become what one refers to as "an old lady" and I was treated as such. No doubt this was partly due to the fact that I was feeling the impact of my car accidents of 1937. As my limbs became paralyzed slowly but surely, my activities diminished. My life became less active and I had time to think about what was going on in the world [...] (translated from French, La Santé 11).

Grace Gassette died in Vermont on May 8, 1955 at the age of 84. She never married or had children:

All my life I had heard about the inheritance of illnesses, and, seeing my physical state, I decided, very early, that I did not have the right to marry, to have children to whom I would transmit my heritages. I spoke to no one about my resolutions or the reasons why I took them (translated from French, La Santé 38).

Sources on Grace Gassette