French Hospital No. 53, 1914 – 1917

As early as 1913, the French Health Service began planning for the enormous number of hospital beds that would be needed in the event of a large-scale war. The French Red Cross was charged with opening and furnishing "auxiliary hospitals" all over the country. These were either mobile units or buildings repurposed as medical facilities. Paris alone had approximately 300 military hospitals, a number of which were auxiliary sites: former hotels, primary and secondary schools, train stations, and libraries (Institut de France).

Thanks to the generosity and quick action of Elisabeth Mills Reid, 4 rue de Chevreuse became an auxiliary hospital as well. In 1914, at the recommendation of the American Embassy in Paris, the thirty-five residents of the Girls' Art Club hastily returned to the United States. At first, the property sheltered forty babies from the nursery at Parc St. Paul in Chaville, a town close to Paris. The babies were eventually placed elsewhere and Reid implemented plans she had made with the wife of the American ambassador, Mrs. Myron T. Herrick, to convert the Club into a medical facility for the French Red Cross.

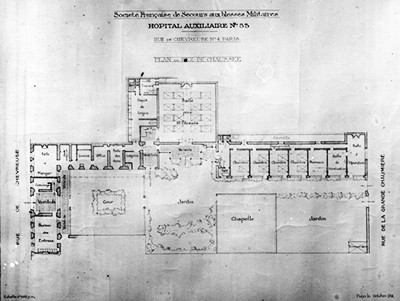

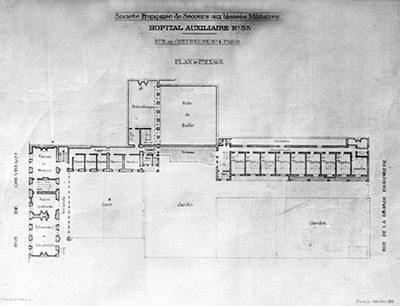

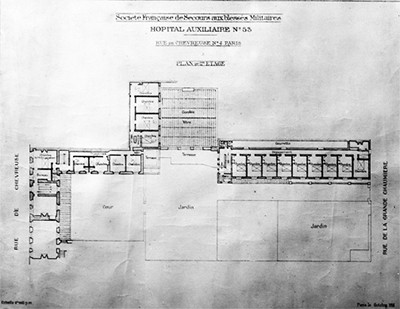

Architect André Vincent was appointed in 1914 to design and oversee the renovation, which was fully financed by Elisabeth Mills Reid.

Transforming the Girl's Art Club

Transforming the Girls' Art Club into an auxiliary military hospital with 50 beds necessitated many structural changes (Chambre des Notaires de Paris report, 1925).

Vincent converted the art studios on the ground floor of the annex building into a pharmacy, a sterilization room, a surgical area, and several recovery rooms. New bathrooms were added on the ground and upper floors; the terrace between the new and old buildings became a glass-enclosed passageway facilitating access from offices to sickrooms; the exhibition hall was converted into a 16-bed area for the wounded; and the furniture depot near the exhibition hall was repurposed into a bathroom, toilet, and linen depot. The story above the library was partitioned into four recovery rooms.

The reception area on the rue de Chevreuse was also altered. A waiting room was created opposite the porter’s lodge; behind it was the dining room. The offices of the doctor and the secretary were located directly above and could be accessed from a new staircase built next to the porter's lodge. The terraces and verandas served as resting areas that enabled patients to enjoy daylight, fresh air, and views of the gardens.

On November 25, 1914, the New York Herald (European Edition) announced the many changes that had been made to the property (2):

The Hospital

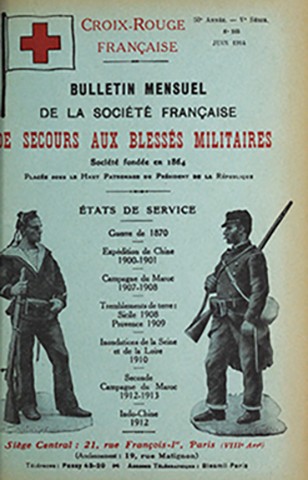

The former residential and social club for American women artists was now filled with hospital beds, sterilization rooms, and operating theaters for surgical procedures. A large sign was hung over the front door on rue de Chevreuse: “Hôpital auxiliaire n° 53, rue Chevreuse, n° 4. Fondation de la Compagnie des Notaires de Paris et du département de la Seine.” The hospital was administered by the Société de Secours aux Blessés Militaires (SSBM) of the French Red Cross.

The hospital opened on November 12, 1914 and the first group of wounded soldiers arrived on November 21. The initial cohort comprised 32 wounded soldiers but by May 7, 1915, the hospital was operating at its maximum capacity of 50. Of the 456 soldiers who convalesced at 4 rue de Chevreuse between 1914 – 1917, from corporals to generals, only four died: three of gangrene in 1915, and one of fatal shell wounds in 1916. All religious services, including the four funerals, were conducted by the priest of the nearby Notre-Dame-des-Champs church.

During the early months of the war M. Révillon from the Chambre des Notaires oversaw the hospital. He was replaced by Edmond Deugnier on December 29, 1914, who mainly relied on his deputy, the architect André Vincent, to manage day-to-day logistics. Deugnier and Vincent remained on-site for the duration of the hospital's existence. The chief doctor was A.M. Lesné and the head of surgery, until June 23, 1915, was Dr. Bonamy. Dr. Desmarest then served as the head of surgery until 1917, although the majority of the medical tasks were handled by two volunteer physicians from South America, Drs. Conto and Cisneros. An accountant faithfully recorded all expenses, and Roselle Van Allen Shields, former director of the Girls’ Art Club, served as the hospital’s liaison to Elisabeth Mills Reid. More than 50 nurses worked at the hospital over the course of its three-year existence, devoting their time and skills to round-the-clock care for France’s wounded.

Special events were organized to lift the men’s spirits: recitals by Bonamy’s wife, a talented singer; concerts by musicians from the Moulin de la Chanson, the Chat Noir, and the Opéra-Comique; plays by actors from the Comédie-Francaise; and magic shows, which were especially favored by the soldiers. Holidays like Easter, Bastille Day, and Christmas were celebrated with festive dinners, entertainment, and games. Reid was especially generous at Christmas, donating the tree and many gifts.

The hospital regularly welcomed official visitors, including American ambassadors, the Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Amette, French generals, and President Raymond Poincaré. He visited on September 29, 1915, accompanied by the American ambassador and other high officials, an event noteworthy enough to be reported in La Croix (October 3, 1915). Earlier that year, General Pau led a ceremony at the hospital, attended by the American ambassador, the Mayor of Paris' sixth district, and other notables, honoring several soldiers for their bravery (The New York Herald, European Edition, June 29, 1915, 1).

The hospital was financed by the Chambre des Notaires (they provided a monthly stipend of 5,000 francs), government subsidies for food (2 francs per soldier each day), and substantial financial support from Elisabeth Mills Reid. According to theChambre des Notaires report, the hospital's success was largely due to her beneficence: she not only gave them the property, but also paid for lighting and heating, and made additional contributions whenever she visited Paris (50).

The notaries also sponsored a donation drive, "Vestiaire du Soldat," which provided necessities for healed soldiers to transition back to the front or to civilian life. Those returning to fight received two shirts, two pairs of underwear, a pair of shoes, two handkerchiefs, two towels, soap, a belt, a head covering, paper and crayons, and other miscellaneous items; those returning to civilian life received a full suit, a wool sweater, two shirts, underwear, two pairs of socks, and shoes. Between Reid and the notaries, this donation drive amassed nearly 30,000 francs, enough to fund the care packages through 1917.

The successful auxiliary hospital at 4 rue de Chevreuse closed on October 12, 1917. Once the United States had entered the war, Elisabeth Mills Reid decided that the property should be dedicated to helping wounded American soldiers. The French officially departed on October 20, leaving behind their equipment and instruments. They were dismayed at being forced to leave, but respected Reid's desire to support her countrymen.

Sources

- "Ambulance Is Installed in American 'Girls' Club." The New York Herald (European Edition), November 25, 1914, p. 2. International Herald Tribune Historical Archives.

- "American National Red Cross photograph collection." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

- "Americans in Paris Give Homes to Babies." The News-Herald, September 11, 1914, p. 1. Newspapers.com.

- Deugnier, Edmond. La Chambre des Notaires et du département de la Seine pendant la guerre 1914-1918. Paris, 1925, print. RH Archives.

- "La Croix Rouges et les ambulances." New York Herald (European Edition), June 29, 1915, p. 1. International Herald Tribune Historical Archives.

- "Les hôpitaux auxiliaires." Institut de France.

- “Petites nouvelles.” La Croix, October 3, 1915. p.8. RetroNews.