Eugenie Frederica Shonnard, 1886 – 1978

Eugenie F. Shonnard was born on April 29, 1886 in Yonkers to wealthy parents, whose land had been granted to the Shonnard family by King George III. Her father served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Her mother, Eugénie Smyth, had been born in Paris and lived in France from 1854 to 1863; she was descended from Francis Lewis, one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. As a child, Eugenie developed a love for animals that inspired her art and enlivened her everyday life.

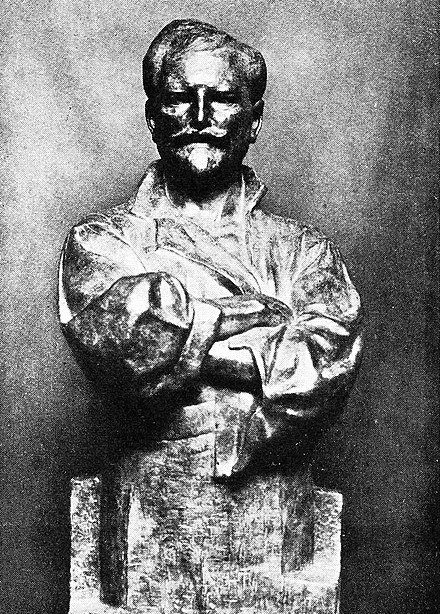

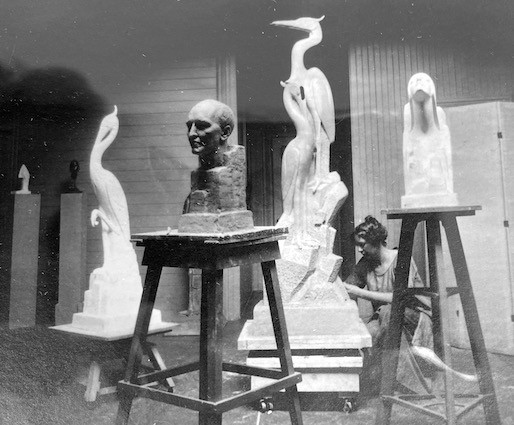

Eugenie studied at the New York School of Applied Design with Alphonse Mucha between 1905-1907, ultimately deciding that she preferred sculpture over drawing and painting once she discovered the admirable qualities of clay (Chassé, 1924, 92). Her bronze bust of Mucha, which she claims to have completed in 1907, is a striking example of her esteem for the man who would launch her career and remain her friend for years to come (Loomis). Although he was disappointed that she opted for another form of artistic expression, Mucha appreciated her talents as a sculptor. For many years Eugenie remained close to the Mucha family, even teaching one of the sons how to sculpt frogs. Years later, the very same son visited Shonnard in Santa Fe to find out what had happened to the magnificent portrait bust she had made of his father. Shonnard explained that the bust, once exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, had been melted down in WWII to make weapons (cited in Runfola).

When Eugenie’s father died, the Shonnard family lost the estate and their financial resources decreased considerably. Mucha proposed that Eugenie go to Paris, where the arts were thriving and the cost of living was much cheaper than in New York. He also left New York and returned to Czecholovakia, where he wrote a letter of introduction for Eugenie to Rodin in 1910. Rodin replied that he could not accept her as a student but that she should still go see him:

My Dear Mucha, Thank you very much for your kind letter, which was so loving. As far as Miss Shonnard is concerned, you will understand that it will be difficult for me to take her on as a pupil. It is, unfortunately, not possible. But she will come to see me from time to time to show me what she has been doing. Send my respectful regards to Madame Mucha and believe me, your loyal friend, Aug Rodin (translated from French, Archery).

Eugenie and her mother sailed for France on November 11, 1911. They stayed in Paris until the onset of WWI and later returned for regular visits after the war ended.

Although Eugenie had already shown some of her work in New York City galleries, she perfected her sculpting craft and launched her exhibition career in France. She first enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she benefited from Auguste Rodin’s and Antoine Bourdelle’s teaching and critiques between 1911 and 1912. Before meeting Rodin one-on-one, she decided to mold a bust as an example of her skills. She selected a man from the open air models’ market on the rue de la Grande Chaumière to pose for her. When Shonnard brought this sample head to Rodin, he immediately recognized the same model he had used for his bust of St. John the Baptist. This coincidence set the stage for Eugenie’s long and fruitful relationship with Rodin, whom she credited with training her artistic eye:

Now, if I am going to make a drawing of you I have what I need in the way of pencils or pen or brush and my paper. I do not look at it. I look at you, and I try to make my mind and my hand work together. The impression of my mind I try to express in an outline with my hand (cited in Loomis).

While many sources frequently name Rodin as her mentor, Shonnard also worked in Bourdelle’s atelier for several years after leaving the Académie. Not only did she appreciate his inclination for architectural sculpture, but she also extolled his teachings and constructive criticism (Loomis; Letter to Bourdelle).

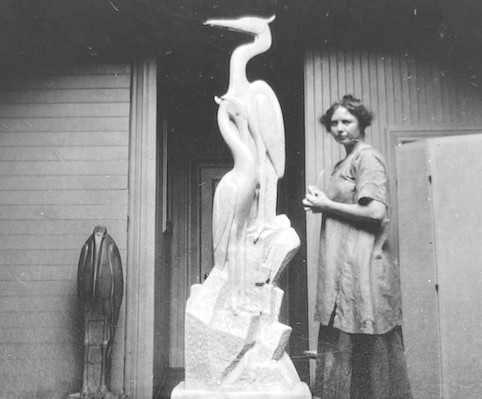

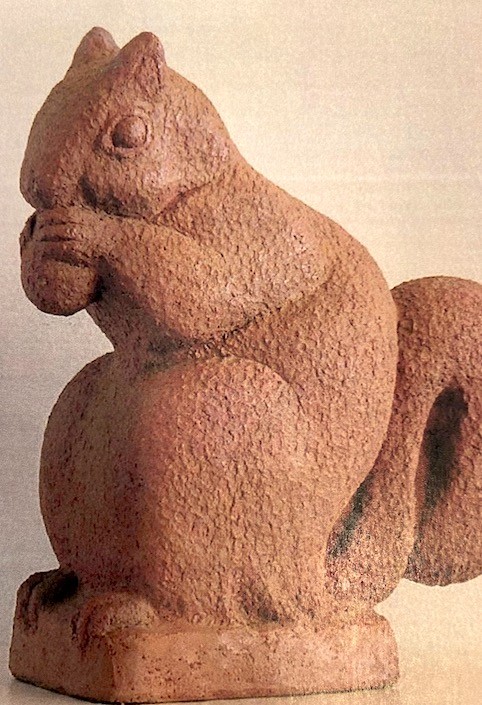

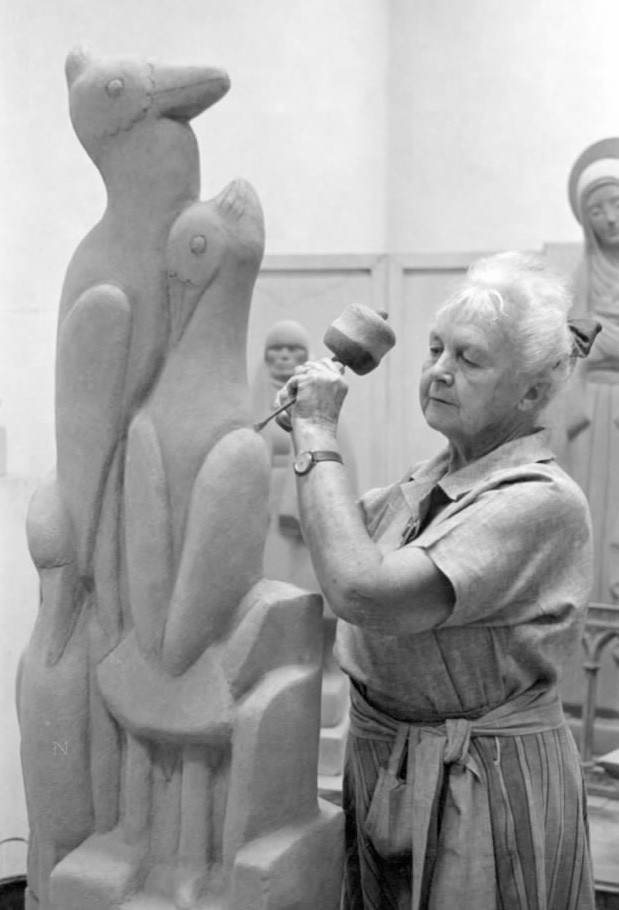

In addition to her formal training, Shonnard was driven by an inner passion that led her to master molding and sculpting techniques using distinct raw materials: clay, terracotta, sandstone, plaster, granite, marble, ceramics, bronze, metal, mahogany, and oak. She even wrote a brief text on the importance of selecting the right medium to convey one’s feelings and ideas:

[…] the very materials in which a sculptor works have in themselves their own peculiar characteristics. The choice therefore of one’s materials is of great importance to the full vitality and emotional content of a sculptor’s composition, as well as to its immediate environment. For bronze, wood, terra cotta and stone, each have their own personalities and life so to speak. So their individual qualities should be well considered before a sculptor makes his choice of material. And the fundamental characteristics of his chosen material must never be overlooked or lost if a piece of sculpture is to reach its highest artistic expression (“Sculpture and the Southwest”).

Throughout her life, Eugenie explored the question of medium/material by sculpting the exact same form using different substances. She even invented her own compound, which she called keenstone, a lightweight cement resistant to rain and snow: “You can use it like clay and build it up or you can let it set into blocks that can then be carved. If it breaks, it can be mended and it takes all kinds of weather” (cited in Black).

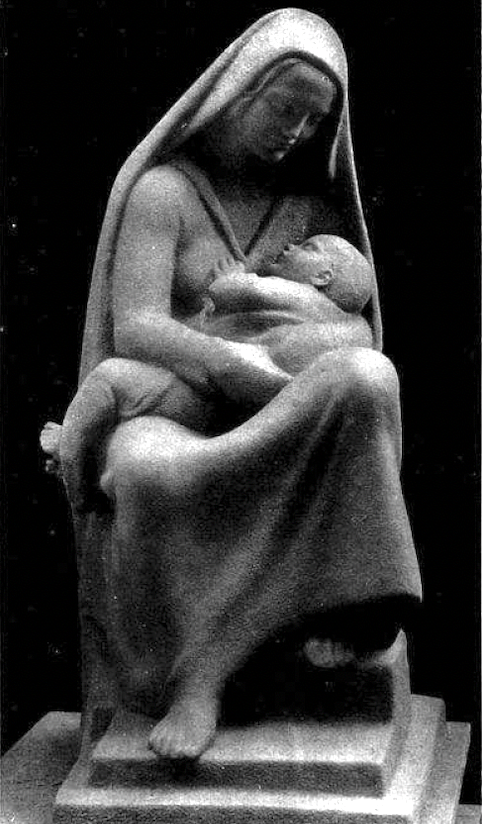

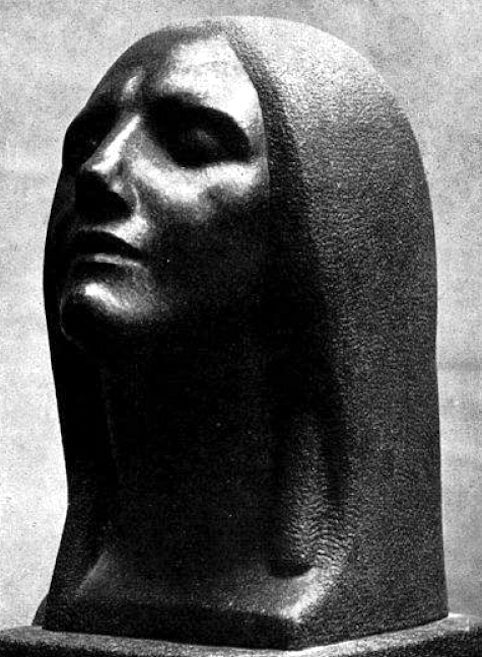

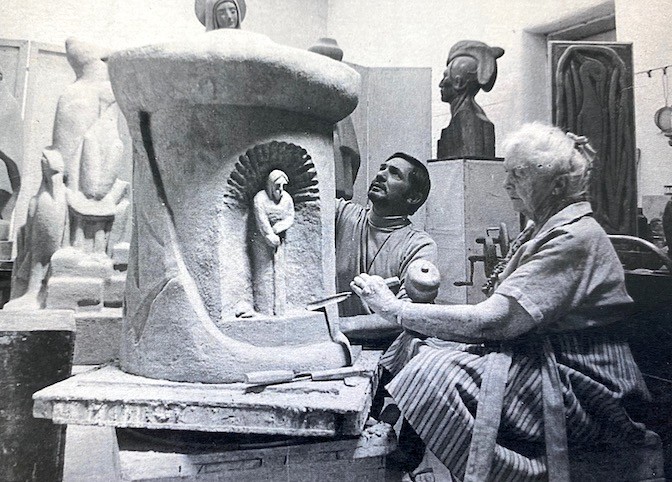

Shonnard had a spiritual disposition and was interested in representing the interior lives of her subjects. Her sculptures of people and animals were not mere portraits; they aimed to capture their essence – and their deep significance. Shonnard's pieces have been described as examples of serenity, simplicity, and fortitude. Sculptor Andrea Bacigalupa, who collaborated on several works with Eugenie Shonnard, characterized this spiritual quality of her art: “The works take on a presence – so much so that it is fairly mystical. One has the sense of never being alone in the studio” (“Rodin’s Student […]”).

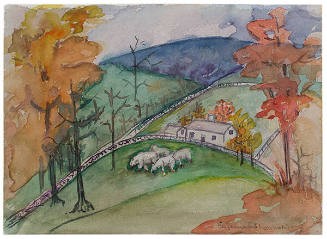

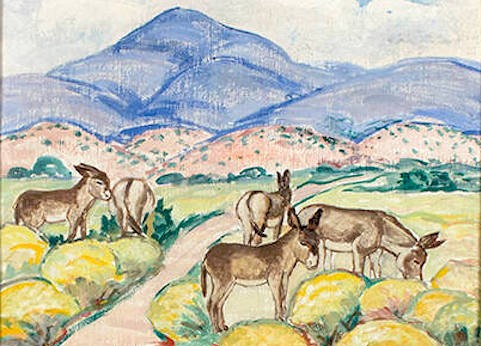

Although best known for sculpture, Eugenie Shonnard was a versatile artist. In addition to statues and monuments she also painted oils and watercolors, produced bas-reliefs, carved furniture, designed rooms, and wove textiles. The breadth of her imagination found expression in art and in communing with plants, animals, and other people with an affinity for nature. Shonnard often had a difficult time parting with her sculptures, preferring their companionship to the money they brought in (“Letters, furniture given to Museum”).

Even so, she had been exhibiting her work from an early age, earning critical acclaim that grew as she evolved over the years in France and the U.S. From the very beginning of her stay in Paris (at 11bis rue du Val de Grâce), she was accepted into various exhibitions:

- 1912: Salon des Beaux-Arts. In addition to Shonnard, several other American Woman's Art Association (AWAA) artists participated, including Constance Bigelow, Minerva Chapman, Della Garretson, Sarah Morris Greene, Malvina Hoffman, Ethel Mars, Juliette Nichols, Eleanor Norcross, Grace Ravlin, Florence Upton, Catherine Watkins, Gertrude Whitney, and Alice Wright (“The New Salon Opens;” “Opens Art Salon in Paris”).

- 1913: AWAA annual exhibition at the Girls’ Art Club.

- 1914: AWAA sculpture exhibition at the Girls’ Art Club. Shonnard showed three heads of “old peasant women” (“U.S. Women Hold Sculpture Exhibit”).

- 1914: Salon des Beaux-Arts. Other featured AWAA artists were Elizabeth Nourse, Minerva Chapman, Ethel Evans, Anne Goldthwaite, Lucy Lee Robbins, Grace Turnbull (“Americans in the Salon;” “Buffalo Painting […]").

The onset of WWI forced Eugenie and her mother back to New York in September 1914. They had wanted to stay in Paris but U.S. government officials ordered all women and children to return home so they sailed on the last steamer out of Le Havre, France. In New York, Eugenie studied under James Earl Fraser at the Art Students League for an unknown period. Before moving to Manhattan, she and her mother lived in Mt. Vernon with her uncle Clifford, an editor for the New York Times Book Review, for whom she made a portrait bust. A chance encounter with the director of the Bronx Park led Shonnard to a commission to sculpt the Zoo’s iconic gorilla, Dinah – a project that took months of intense interactions in a room alone with this recalcitrant ape. The clay bust was revealed at the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the New York Zoological Society in May 1915.

During this period, Shonnard exhibited her work in several New York galleries and museums:

- 1915: Academy of Design. She exhibited “Russian Wolf Hound,” which the New York Times reviewer claimed: “[…] is beautiful and convincing, but lacks the vigorous sentiment of life that is felt in the work of such men as Destovic and Sandoz” (“Contrasts and Sculptures […]” 62).

- 1915: Gorham Galleries Annual Sculpture Exhibition.

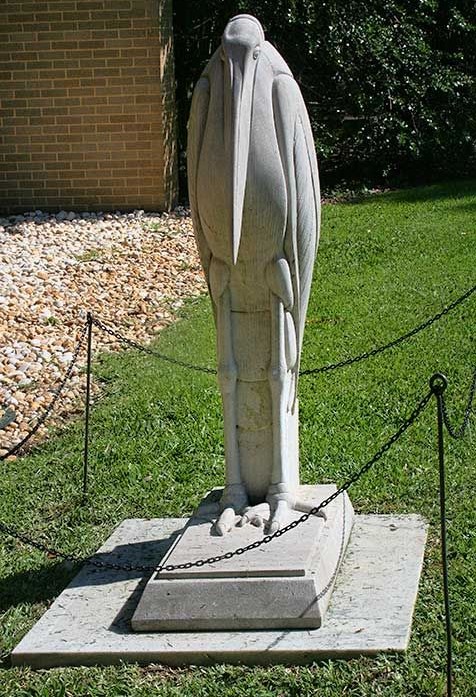

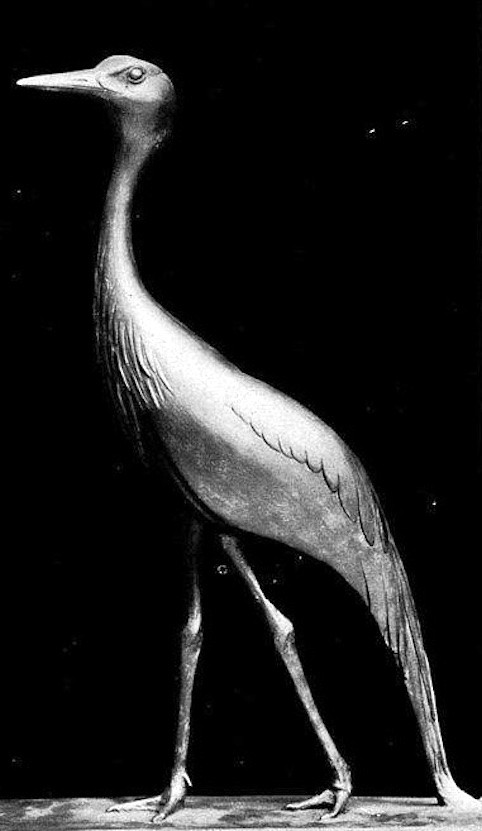

- 1916: Gorham Galleries. In this garden show, Shonnard exhibited a birdbath and her marabout, of which a critic declared “wisdom itself lies in the bird’s eyes.” AWAA artist Anna Ladd exhibited a merman (“The World of Art”).

- 1916: Academy of Design. This show dedicated to the memory of William Chase (Cortissoz).

- 1919: Brooklyn Museum of Art "Wildlife in Art" Exhibition. Shonnard showed her marabout sculpture and a wrought iron panel for a bird cage (“The Birds and the Beats […]”).

- 1919: Metropolitan Museum of Art Courbet Centenary Exhibition (Field). The museum later acquired her 1922 bronze, “Head of a Breton Peasant,” which was shown at Gorham’s in 1925.

- 1919: Touchstone Galleries. In this garden sculpture show, Shonnard exhibited a pair of handwrought vases (“Notes on Current Art”).

When international travel and communications resumed, Shonnard wrote to Bourdelle and his wife to inquire about how they had fared during the war. Her 1919 letter to Bourdelle’s wife clearly demonstrates that France was beckoning her to return. She missed the ethos of Paris but also understood the practicality of a more economical way of life than was possible in New York (Loomis):

“I am frightfully impatient to get back to Paris. Perhaps it will be in the Spring. My soul just starves here – New York and my hair is turning grey. It will probably be white after another Winter here. I get so lonesome for Paris that it makes me sick at times.”

In an earlier 1919 letter, Shonnard had urged Bourdelle to send photos so she could promote his work to gallerists and art critics in New York: “Mr. Bourdelle, I only see three examples of your work in this city, which is a shame! Our museum doesn’t even have one of your sculptures, which is outrageous!!!!!” (translated from French). It is unclear if she ever succeeded in her efforts on his behalf.

Eugenie and her mother sailed back to France in early 1920, living in Paris on the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, and spending summers in Plouanach, Brittany (ca. 1921, 22, 23, 24). Passport records show that they also traveled to Belgium, Holland, the British Isles, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and Egypt.

Once again Shonnard regularly participated in French Salons and gallery exhibitions:

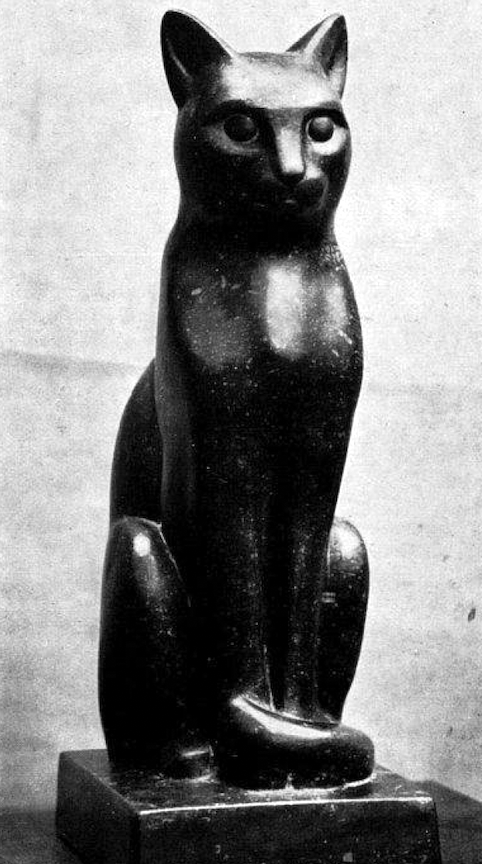

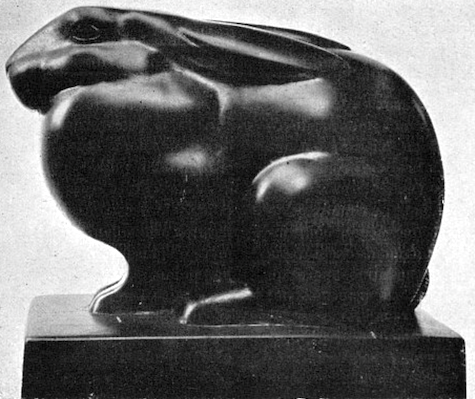

- 1922: Salon d’Automne. She showed her marabout, a cat, and two rabbits (Chassé, 1923).

- 1922: Salon des Beaux-Arts. She exhibited “le chat” and “les deux bretonnes,” which a critic described as being “of delicate observation” (“Nos échos”).

- 1922: American Women’s Club’s Third Exposition of Paintings and Sculptures. Shonnard's entries were bronze statuettes of peasant types: “The female personages are treated with a surer hand than the male, but all reveal a vigorous talent” (“Works Shown […]”).

- 1923: Salon d’Automne. A critic compared her style of animal sculptures to that of Francois Pompon (“Le Salon d’Automne”). One of her pieces was “Le Marabout” in granite (Sarradin). She also showed a cat in black granite, and two rabbits, one in bronze and the other in ebony (Chassé).

- 1923: Salon des Tuileries. Shonnard's two gray heads in granite, were deemed “the best” of the sculptures on view (Longnon).

- 1923: Salon des Beaux-Arts. Her three exhibited heads were supposedly “of perfect style” (“Le Salon”).

- 1924: Salon des Tuileries. She showed “Une vielle bretonne” in granite and “Un lapin” in bronze. (“Au salon des Tuileries”).

- 1924:Salon des Beaux-Arts. Her entry was a group of birds in island wood (“Les salons de 1924”).

- 1925: Salon des Beaux-Arts. One critic declared her wooden statuettes remarkable (T.S.).

- 1926: Salon des Tuileries. A sculpture of a heron (Sanchez).

- 1927: Salon des Tuileries. "Femme indienne des États-Unis," in terracotta (Sanchez/Bal).

French art critic Charles Chassé wrote a lengthy tribute of her work, aptly noting htat: “she put great technical talent and remarkable power of work at the service of her inspiration” (translated from French, 1924, 95).

Her 1926 solo show at the Galerie Allard was the crowning glory of her residence in France. The 60-piece exhibition was opened by former U.S. Ambassador to France Myron T. Herrick and Paul Léon, Director of the École des Beaux Arts (T.S.; “Artists and Writers”). In addition to her usual sculptures Shonnard also showed aquarelles, which she had painted in Arizona and New Mexico. Georges Bal reviewed the show for the New York Herald (European Edition) on June 1, 1926 and expressed admiration for her work:

One is really surprised at the sixty odd pieces of sculpture forming this exposition when it is realized that they are the work of a woman. Surprise is accentuated by the fact that she has employed hard materials, such as granite, marble and hard woods. As for the bronzes, it must be added that the sculptor has invented some remarkable patinas with which the works thus presented are covered. With a veritable talent for sculpture, Miss Shonnard knows how to choose subjects from nature and to give them the hieratic character which lends itself best to sculpture.

The Musée du Luxembourg acquired her exhibited bronze, “Lapin aux oreilles couchées,” listed in the Journal Officiel de la République française. Today, this sculpture is in the collection of the Musée Franco-Américain du Château de Blérancourt.

In 1925 Shonnard had been invited by the archaeologist and anthropologist Edgar L. Hewett to move to Santa Fe, with the promise of a studio space at the Museum of New Mexico. Hewett wanted her to document Pueblo culture (“600 Guests […]). Shonnard left France and moved to Santa Fe in 1927, where her mother had bought a historic home surrounded by orchards and fields. Though Eugenie never returned to France, she maintained epistolary ties with various French artists. In 1951, through the sculptor G.C. de Swiecinsky, she offered the Paris Museum of Natural History a granite marabout that she had sculpted from life in a small Parisian zoo. Fully restored in 2022, this sculpture is currently nestled within the Jardin des Plantes.

Mother and daughter continued living together even after Eugenie married engineer and entrepreneur Edward Gordon Ludlam on July 26, 1933. Not much is known about their marriage or his own career path; Ludlam appears as a footnote or parenthesis in most sources about Eugenie’s life. He definitely helped her convert the barn on their property into a studio and he worked with her on wood-carving and furniture-making (“Finds no place […]). Ludlam died after an extended illness on October 13, 1955.

Eugenie settled into the Santa Fe home her mother had purchased and given to her as a wedding present; she spent much of her time in Pueblo villages, learning their methods for creating pottery and producing portraits of Pueblo men and women. She formed "an extremely strong bond with Marie Martinez famed potter of San Idelfonso who taught her much about working in clay" (Flynn 314). Her experiences led to myriad sculptures, bas-reliefs, and monuments honoring Pueblo arts, which were praised by critics as powerful evocations of Native American culture. One such sculpture featured Sioux physician, writer, and civil rights advocate Charles Alexander Eastman (ca. 1920).

Shonnard continued exhibiting and executing commissions throughout her long life. In 1929, two years after she returned to the U.S., she was honored with a large and much-publicized exhibition organized by the Tulsa Art Association of 26 watercolors and several sculptures. Her work was acquired by many museums and private collections and was featured in dozens of shows. Shonnard sculptures adorned private gardens, public parks, and the interiors and exteriors of grand buildings. During the Great Depression, she was involved in the WPA Federal Art Project. In 1940, she won the grand prize at the New Mexico State Fair for her bronze cat statue (“600 Guests […]”). In 1954, a retrospective exhibit of her work was held at the New Mexico Art Museum (Weber); she was also awarded an honorary fellowship in fine arts by the School of American Research and Museum of New Mexico.

Shonnard's professional associations and affiliations were numerous. She was a member of the National Sculpture Society and, in 1923, was named an Associate Member of the Société nationale des beaux-arts (“Ponts des Arts;” “Informations;” “Notes d’Art”). In 1924, she was elected as a member of the Société du Salon d’Automne (Le Rapin) and was still listed as a member in the 1930 catalog of the Salon d'Automne, with her address given as 117 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in Paris, though by then she had settled in New Mexico.

With unflagging passion and stamina, Eugénie created and exhibited until she died, just shy of 92 years of age, on April 5, 1978 in Santa Fe.

She bequeathed her house and its contents to the Museum of New Mexico Foundation, which now uses the space as its headquarters (“Shonnard House Plaqued;” “Resculpting History […]”). Her papers included letters, diaries, ledgers, clippings, scrapbooks, notebooks, genealogies, family histories, and over 3,000 family photographs. Her paintings, sculptures, tools, and the family’s Victorian furniture went to the New Mexico Museum of Arts (“Letters, furniture given to Museum”).

The finding aid for Shonnard's papers can be consulted at the New Mexico Archives Online.

Sources on Eugenie Shonnard.