Blanche Dillaye

Blanche (Annie) Dillaye was born on September 4, 1851 in Syracuse, New York into a well-to-do French-American family; she was the only child of lawyer and businessman Stephen Devalson Dillaye and Charlotte B. Malcom. In early childhood, she had already shown an aptitude for drawing and was thus boarded at the Chestnut Street Female Seminary, which became the elite Ogontz school for Young Ladies near Philadelphia. This rigorous private school had been founded in 1850 by her Quaker aunt, Harriette A. Dillaye (and Mary L. Bonney, her classmate) as an alternative to the traditional finishing school. Here, girls from ages 13 – 18 received a liberal arts education that included humanities, science, physical education classes, and a department of Pencilling, Crayon and Painting in Oil and Watercolors.

Around 1882, Dillaye studied under etcher Stephen Parrish whose pupils included Florence Este, Eleanor Greatorex, and Sarah Dodson, Gabrielle de Veaux Clements, all of whom eventually studied in Paris and were involved with the American Women’s Art Association (AWAA). In her address to the Columbian Exposition, Dillaye recognized that “the first coterie of women etcher, [...] received their first impulse and gained command of the subtle resources of their art from the generously proffered instruction of Stephen Parrish” (Emily Sartain, “Women in Business,” Biennial of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1896, p. 327). She attended the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, taking a class in etching with Stephen Ferrier from 1883 – 1884, together with Gabrielle De Veaux Clements and Edith Loring Peirce Getchell. She also trained with Charles Woodbury in Annisquan and Shinecock, Massachusetts in the summer months of 1898.

In the 1890s, Dillaye adopted the snail as her “sign and seal.” According Gladys Engel Lang, “She signed many of her drawings with a tiny sketch of a small snail as a play on her French name, pronounced ‘delay,’ and took as her motto Shakespeare’s tribute to the snail: ‘He goes but slowly, but he carries his house on his head’” (202). A reporter who visited her studio asked why she had an ivory snail among her decorations; when Dillaye responded that it was her symbol, the reporter replied: “The only thing slow about you is your name” (Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 1896, p.11).

Indeed, there was nothing slow about Dillaye’s ascension in the art world; accounts recall an energetic, persevering, and passionate artist who mobilized the art community by organizing exhibits, sitting on juries, and participating on hanging committees. Her dedication, as well as that of her fellow etchers, did much to elevate the art of etching, which was initially perceived as a lesser art – an idea that reporter Edwina Spencer qualified as “a relic of artistic barbarism, as much so as the crude judgment which measures the importance of a painter’s achievement by the magnitude of his canvas” (cited in the Buffalo Courrier, September 29, 1901, p. 1). By 1896, Dillaye had already been portrayed in newspapers as “Probably the foremost etcher among women artists of this country [...] indeed there are very few men whose work is entitled to superior rank” (The Gazette, February 11, 1896, p. 3).

Blanche Dillaye’s personal and professional life was split between the U.S. and Europe. She never married, devoting herself entirely to her chosen career. Much of what she painted or drew in different parts of France, Germany, Holland, Italy, and England was shown at exhibits in eastern, midwestern, and southern states of the U.S.

UNITED STATES

In the U.S., Dillaye was mainly active in Philadelphia, where she had several studios, among them with fellow artists Edith L. Pierce, then Florence Este (1885). One of her ateliers was completely destroyed in the 1910 fire that devasted a studio building in Philadelphia. From 1889 to the early 1920s, she was an art instructor, and later department head, at the reputed Ogontz School for Young Ladies, where she herself had been trained. Here, she staged numerous exhibits of her own work, and that of her students and fellow artists. Teaching art did not prevent Dillaye from producing art, especially since the school operated from October to May, thereby allowing her to travel for extended summer months. It also did not prevent her from exhibiting her paintings and etches. Outside of participating in the many exhibits of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), the Plastic Club, the Boston Art Club, and various watercolor and etching clubs, Dillaye also presented in numerous other group and solo shows, notably:

- 1887, The Women Etchers of America Exhibition in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where she showed 37 etchings of her work in Holland.

- 1895, Art Student’s Club in Worcester, Massachusetts

- 1893, Boston Art Club Fine Arts Exhibition: “Gloucester Downs: September.”

- 1893, World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. She was the chair of the committee appointed to decorate the ladies’ parlor in the Pennsylvania Building and responsible for the etching exhibit, which included 72 pieces, 50 of which represented women artists from Philadelphia. By special request, she also read an address on “The Art of Etching and Women Etchers.”

- 1895, Atlanta Exposition: “Mist on the Cornish Coast,” silver medal.

- 1896, Student art League Exhibition in Buffalo, where her etching was appraised as “the best work in dry point” and she was identified by the Buffalo Courrier as a “Philadelphia girl with a French name (and a French genius for technique) (November 8, 1896, p.11).

- 1897, Fifth Annual Exhibit of the Baltimore Association: pencil drawings and watercolors.

- May 1901, Pan American Exposition, Buffalo: “Mist on the Cornish Coast.”

- April 1904, Worcester Art Museum: A collection of 23 paintings.

- May 1904, Mechanics Institute in Rochester, New York: Solo exhibition of 23 watercolors.

- November 1904, Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts: 57 paintings and watercolors were placed on exhibit as an homage to Dillaye who was born in Syracuse.

From 1904 onward, Dillaye’s art figures in innumerable exhibits, at least twice or three times a year, throughout the U.S., many devoted to watercolors and etchings. Three exhibits are worth mentioning:

- 1921, Art Alliance in Philadelphia: Comprehensive display of all her media – oil, watercolor, drawing, etching.

- 1927, Plastic Club: Comprehensive exhibition honoring Dillaye.

- 1931, Conservation Exposition, Knoxville, Tennessee. She received a gold medal for watercolor.

Dillaye not only taught, painted, and exhibited, but she also acted as an effective advocate for artists. She gave speeches on the history of etching and actively participated in a several art clubs on the east coast; as a member, she headed their boards and worked on hanging committees or as a juror:

- The “Plastic Club:” title coined by Dillaye in reference to unfinished works of art which are in a "plastic state;" elected President in 1897 and later staying on as Vice-President (Herzog 16).

- New York Etching Club

- New York Watercolor Club

- Philadelphia Watercolor Club (Vice-President from c. 1905 onward)

- Black and White Club of New York

- Civic Club’s committee on art education and classrooms

- Fellowship of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts: Founded in 1897and still active in 2024. Dillaye was one its Vice presidents

- Women’s Art Club of New York

- Founding member of the Philadelphia Society of Etchers (1927)

In addition, Dillaye illustrated several publications, including an 1884 portrait of Charlotte Bronte for a new edition of Jane Eyre. She also wrote illustrated articles and a play: for example, “Bird-House Town” was published in the Monthly Illustrator (1895, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 321-324); her one-act play “Masks” was staged several times at the Insurgent Theatre and at the Fellowship of the Academy of Fine Arts (1918, to meet expenses of the Fellowship Ambulance Fund). Newspapers articles reported that she was “as versatile with her pen as with her brush.”

Around 1908, Dillaye bought a small grapefruit farm in Coconut Grove, Florida. She transformed a small house on the property into a studio and arts and crafts store where she sold old jewels, hand-painted jewelry, and art objects collected in Europe. She began to work in gold and silver smithing, and also painted furniture.

EUROPE

Like many American women artists of her day, Dillaye left the shores of the U.S to explore the artworld overseas and, especially, to paint or draw from life: mainly village scenes, landscapes, and watercapes. Her love affair with Europe, especially Paris, began in the Spring of 1884, when she embarked on her first trip to Holland, together with her friend and fellow artist Edith Loring Peirce (married Getchell). She initially went to Dordrecht in Holland and then traveled to England and Paris. Three of her etchings were shown at the exhibition of the London Society of Painters-Etchers in Liverpool, England. In 1885, she exhibited an etching, “Au Marais,” at the Salon de la Société des Artistes français. At the time, she lived on a small street near the Champs Elysée (5, rue Lord Byron) and studied with impressionist painter Eduardo Leon Garrido, who was born in Spain but lived in Paris where his paintings of gallantry and elegant women enjoyed great success.

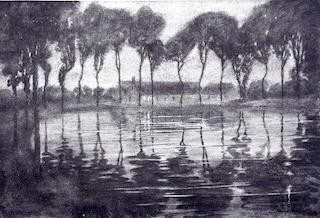

![Blanche Dillaye, "On the Grande Moran [sic], Crécy-en-Brie," c. 1894, etching. The Philadelphia Inquirer, October, 1894, p. Blanche Dillaye, "On the Grande Moran [sic], Crécy-en-Brie," c. 1894, etching. The Philadelphia Inquirer, October, 1894, p.](/sites/default/files/styles/cu_crop/public/content/Dillaye/Etching%20The_Philadelphia_Inquirer_Sun__Oct_7__1894_.jpg?h=f7a665a6&itok=YgzpWmMu)

Her regular back and forth between the two continents really began in 1894, when she spent an extended summer in Crécy-en-Brie. This picturesque, once-fortified, town known as the Venice of the Brie was favored by many artists because of its old-world charm and proximity to Paris (25 miles to the east). In a letter to the Philadelphia Times, Dillaye provided a sardonic description of the swarms of young women who had invaded its walls:

It is amusing to come upon the streets of this famous old town on a morning and find their still, staid, almost deserted air disturbed by a new and awful creature known as the American art student. I did not know that this particular tailor-made object ever escaped far beyond the reticent walls of the life class (I say she advisedly, for she predominates) but here she is in her pinafore aprons, bedaubed with paint from top to toe – no, not to toe – for she generally wears a short skirt which escapes the ground with a miss that is as good as a mile. In low shoes and lank ankles, with a palette as big as a barn door on her thumb, her sketching traps slung over her shoulders or lugged under her arm, she strides with long, masterly steps, through the market place, a conquering army-air about her that would hardly seem to be justified by the canvas she boldly exposed to view with perhaps her maiden effort in landscape on it. But probably the most striking feature of this home product is her hat. [...] Her shoes too should not be passed by – indeed they could not if you met her in one of those narrow streets. [...] This is the American beauty one sees at home in these old streets. [...] I only wonder in my silent chamber if she would dare so to carry herself at home, or if it is only for the foreigner she poses thus. [...] It is hardly to be expected that they escape the French wit. [...] (cited in The New York Times, August 23, 1894, p. 4).

True to her Gaelic forebears, Blanche Dillaye began to stay in France for extended periods of time.

- 1895 – 1897: she sailed for Marseille in August of 1895 and sketched in Provence, Crécy-en-Brie, St. Lo, the Mont St. Michel, and other favorite American sites in Brittany and Normandy.

- 1899-1902: in the summer of 1899, she sailed to Holland with her students and artists Margaret Lippincott, a certain Miss Galler, and Elizabeth Bonsall. She then went to France where she sketched in the area of Fontainebleau and later settled in a studio not far from Paris (3 rue de Bagneux in Chatillon) with a certain Miss Seaborn, who would be studying at the Sorbonne. In December 1899, she showed a watercolor, “Boston Commons in Winter,” at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the American Women Artist Association, which took place at the Girls’ Club. The exhibition, which included 89 paintings, several miniatures and watercolors, nine sculptures, and some porcelain designs was hailed by critics: The sixth annual exhibition of the| American Women's Art Association of Paris, at No. 4 Rue Chevreuse, has been a great success. Never before have American artists as a body given such evidence of talent, effort and progress. That there are and have been- in the French capital a number of them who have won a name for themselves on both sides of the Atlantic Is perfectly well known, but that the Association was capable of turning out so much good work must have come as a surprise to many (cited in the Richmond Sunday Times, March 4, 1900, p. 10, quoting the New York Herald).

- After spending the summer of 1901 with Charles Lazar and his class in Salisbury, England, she and Miss Seaborn moved to 53, rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs – three blocks away from the Girls’ Art Club, where several of her fellow artists stayed or exhibited. She was also a member of the American Women’s Art Association, which was housed at the Club. She stayed in Paris through 1902, returning again from May – September in 1903, when she sailed with Emily Sartain, principal of the School of Design for Women.

In a three-year period, she was represented in several important exhibitions:

- March 1901: American Women’s Art Association. She exhibited a painting, sunset with a sea of purple mist, identified as a chef-d’oeuvre, and two etchings: “Mist on a Cornish Coast” and “The River.” Several fellow artists from Philadelphia also exhibited, notably Louise Wood and Florence Este.

- May 1901: Salon de la Société des Artistes français. She exhibited five etchings, including “Brume sur la côte de Cornwall.” Fellow artist, Louise Wood exhibited her painting, “Femme sérieuse.” Both listed their address as 3 rue de Bagneux.

- 1902: The American Women’s Art Association at the Girls’ Art Club. Dillaye was a member of the hanging committee and exhibited a watercolor, “Nuit d’été” and a painting of old houses in the moonlight. Several other Philadelphia artists were represented, notably, Louise Wood, May Post, Mary Perkins, and Meta Vaux-Warrick.

- 1902: Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts. She showed 2 watercolors, “La Maisonette sur le Coteau” and “Nuit d’été,” and two etchings, “Maison à Dordrecht” and “Vieille Rue à Québec” listing her address as 53 rue N-D des Champs. Other American women artists at the exhibition of pastels, watercolors, drawings, and miniatures included: Henrietta Crapo-Smith, Eustice Lee Florance, Florence Este, Elizabeth Nourse, Anna Watson, Louise Wood, May Post, Harriet Hallowell (Fort Scott Daily Tribune, August 4, 1902, p. 2). The majority had also exhibited at the AWAA show in 1902.

1903: Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts. She exhibited three etchings: “La Dernière cargaison,” “Les Vieux quais,” and “Les Chemins de campagne.” She received a silver medal for her watercolors, and was asked to be part of a special exhibit in the Exposition universelle in Lorient, France.

After 1903, we lose trace of her travels abroad, but she did return to Europe in 1911, sailing to Antwerp, and she possibly stayed in Paris through 1912, when she exhibited one last time at the Salon de la Société des Artistes français. The watercolor, titled “Le Carrefour,” listed her address as Monsieur Lucien Lefebvre-Foinet at 19 rue Vavin, site of the renowned oil paint and art supply store. She may not have been present at the time since the store often sent artworks to exhibits, and it seems her work received a medal (The Spokesman-Review, August 16, 1916, p. 8). The outbreak of WWI probably halted her travels to Europe, and we find no other indications that she traveled outside the U.S. in her late sixties or seventies.

Blanche Dillaye died on December 20, 1931 at the age of 80, after undergoing an operation for appendicitis. Her brief obituary was repeated in hundreds of newspapers. We know she bequeathed 9 unsigned etchings and plates to the Arts division of the Library of Congress (and 1 etching and plate by Florence Este), but have no further information on the remainder of her estate. A memorial exhibition of her work was held in Syracuse, New York in 1932.