Alice Morgan Wright, 1881 – 1975

Alice Morgan Wright was a sculptor, suffragist, writer, animal welfare activist, and one of the first American artists to embrace Cubism and Futurism in the early 20th century. Born in Albany, New York in 1881, Alice was the daughter of Emma Jane Morgan Wright and Henry Romeyn Wright, a wealthy commission merchant (New York Times, March 7, 1912, 2).

According to Elsie Y. Heung, "Wright showed a talent for art at a young age, deciding to become a sculptor by the time she graduated from high school" (207). She attended Smith College from 1899 to 1904, where she was the editor of the Smith Monthly and the founder of the Collegiate Equal Suffrage League (Berkshire Eagle 52). Wright was also named Ivy Orator of the Class of 1904 and she delivered an address, “The Freedom of Service,” which foreshadowed her lifetime commitment to various social justice causes (The Boston Globe, March 9, 1912, 8). After college, she studied at the Art Students League in New York from 1905 – 1909, working with James Earle Fraser and Hermon Atkins MacNeil. She exhibited in 1909 at the National Academy of Design (Fahlman 588), and won the Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Gutzon Borglum prizes from the League (Heung 208).

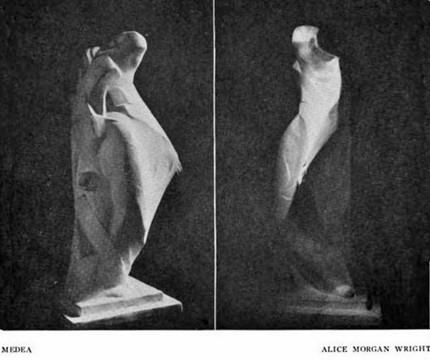

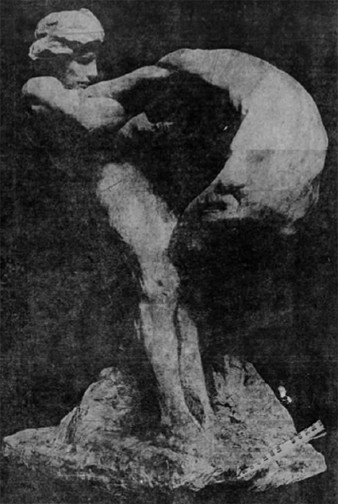

Wright traveled to Paris and resided at the Girl's Art Club from c. 1909 –1912, where she felt quite at home, ate well, and enjoyed interesting conversation (Dennison 34). She attended the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Colarossi, training under Injalbert. While in Paris, Wright participated in exhibitions organized by the American Woman's Art Association at 4 rue de Chevreuse (1910, 1911, and 1914) and the Royal Academy of Art, London (1911). She was also a darling of the Paris Salons, first exhibiting at the 1910 Salon des artistes francais, where she showed a plaster sculpture of Cain. At the 1913 and 1914 Salons des artistes francais, Wright exhibited two sculptures each year. In 1912, she showed two sculpted works at the rival Salon des Beaux-Arts, as well as two stained glass pieces in the decorative arts section. It is believed that her only Salon d’Automne appearance came in 1913.

Wright's suffrage activism began way back in New York City but intensified during her European sojourn and thereafter.

[She] grew interested in the suffragette movement for women’s voting rights when she encountered obstacles to becoming a sculptor. Many men dismissed her ambitions, doubting that she had the strength to manage stone and clay. She was not allowed to sketch nude men in class and resorted to attending boxing and wrestling matches to study the male physique (Smithsonian Art Museum quoting Fahlman, Sculpture and Suffrage, 1978).

At the Girls' Art Club, she was instrumental in bringing suffragists Emmeline Pankhurst, whom she had met on the Atlantic crossing to France, and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, to address her peers. She also joined Pankhurst in London to participate in the English Militant Campaign for Suffrage. Wright was detained on March 4, 1912 along with two other suffragists at the Young Street Post Office, where they had broken a window (Marconi 1). To the dismay of her American supporters, she was sentenced to two months of hard labor in London's Holloway Prison (New York Times, March 7, 1912, 2), where she and her fellow activists protested their treatment by going on a hunger strike. Hard labor for Wright and the others meant: “She will be compelled, with her sisters in misfortune, to scrub the floors of the prison, clean the windows, wash and iron the clothing, etc. used in the prison and, when not employed in this way will have to sew on coarse bagging making sacks” (Buffalo Evening News, March 6, 1912, 1).

Though there was a general public outcry in support of the imprisoned suffragists, there were some who objected to their violent means and bold actions. Mrs. Joseph Gavit, a leader in the Albany suffrage movement who deplored militant actions, was quoted in The New York Times: "She is a young woman who does not take kindly to sympathy, and she is likely to exult in martyrdom for a cause and deprecate any efforts to mitigate her present sufferings" (March 7, 1912, 2). Wright was released early to her family on April 26, physically diminished but steadfast in her commitment to the cause (Detroit Free Press, April 27, 1912, 4).

Wright returned to New York City before World War I and rented a studio at 15 Macdougal Alley in Greenwich Village from 1914 – 1920. She remained politically engaged, serving with fellow Girls’ Art Club affiliates Anne Goldthwaite and Ida Sedgwick Proper on the organizing committee of the 1915 Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture by Women Artists for the Benefit of the Women's Suffrage Campaign. Wright was also an exhibitor at this groundbreaking show. One of her sculptures, “The Keeper of Dreams,” was praised in the Minneapolis Star Tribune: “One realizes that ‘The Keeper of Dreams’ is a composite figure of the whole world of women, who is acquiring the power to make the worthy dreams of women come true” (October 17, 1915, 55).

Wright exhibited her "Wind Figure" at a 1916 show at Marius de Zayas' Modern Gallery, which also featured sculptures by Brancusi, Modigliani, and Wolff (Antliff 62). She exhibited the same piece in 1917 at the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, which she had co-founded that same year. Also in 1917 was a joint exhibition of paintings/etchings by Anne Goldthwaite and sculptures by Alice Morgan Wright at the Women’s University Club in New York (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 21, 1917, 22).

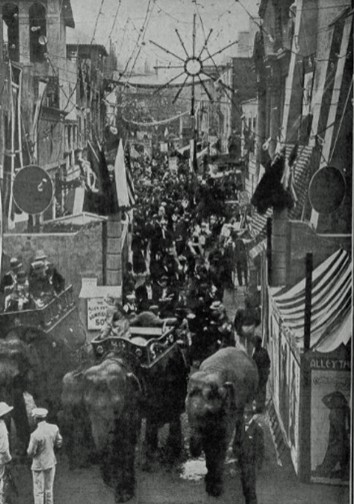

Like so many other American artists who wished to aid in the war effort, Wright participated in the two-week “Alley Festa” in 1917, a fundraising festival/carnival organized by the residents of Macdougal Alley. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was one of the leaders of this highly successful event, which raised nearly $63,000 for the American Red Cross and the Allied War Charities (Clarke 414). A sculptor herself, Whitney temporarily transformed her three-story studio in Macdougal Alley into an “al fresco dining room.” There were also games of chance, many vendors, and a Red Cross Dancing Hall (Gordon 157). In her description of the various sights and attractions of the Alley Festa, Eleanor Booth Simmons described Wright’s studio for the old New York paper The Sun: “Not far beyond Mr. [Daniel Chester] French’s studio is that of Alice Morgan Wright, and anybody who knows Alice Morgan Wright doesn’t have to be told what her studio is featuring for the Festa. They can tell with their eyes shut that the blue and yellow of suffrage, the Suffrage War Relief, covers the front of that studio from the old knocker to the topmost brick of the wall […] Did I say that Miss Wright is going to have grand theatrical presentations in her studio behind the Suffrage War Relief booth?” (June 3, 1917, 7). Simmons also acknowledged another former Girls’ Art Club affiliate participating in the Festa: sculptor Malvina Hoffman was running a soda fountain!

Throughout her adult life, Wright pursued the twin paths of sculptor and political activist. She served as the recording secretary of the New York State Women's Suffrage Party from December 1915 to 1920. In 1916, she partnered with Anne Goldthwaite on a large silk banner in support of suffrage that was unveiled at a New York Giants baseball game on June 3. On that so-called “Suffrage Day” at the historic Polo Grounds, the Giants showed their support by sharing half of the proceeds from the day’s receipts with Votes for Women. Wright also helped found the League of Women Voters of New York State in 1920 and was later awarded the N.Y. State Suffrage Party Medal. Two decades later, she became the chairperson of the National Women’s Party from 1945-1947 (Berkshire Eagle 52).

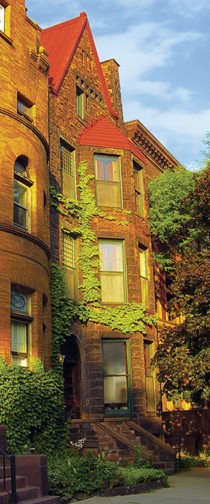

In 1921, Wright returned to her family home in Albany, New York, which had been designed by architect R.W. Gibson for her father. She lived there with her lifelong companion, Edith J. Goode, whom she had met at Smith College. Wright maintained a studio on the fourth floor of the house and, in 1926, found another studio near Goode's family retreat in Woodstock, Vermont (Smith Alumnae Quarterly 89).

According to the Albany Institute of History and Art's catalogue:

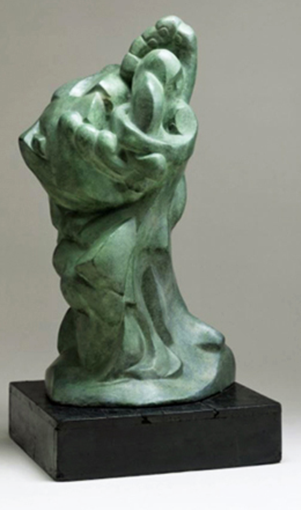

While she is credited with contributing to the development of modernism in American art, she never achieved the status of a major artist. Her output, primarily small-scale sculptures in bronze, marble, and plaster, was neither large nor stylistically consistent. She worked slowly and moved back and forth from a conservative style to modernist works such as "The Fist" that established her significance as one of the few Americans doing abstract sculpture in the first decades of the century (160).

In 1936, the Albany Institute of History and Art mounted a solo exhibition of her work; she also showed at the New York and San Francisco World's Fairs, the Philadelphia Institute of Art, and the Chicago Museum of Fine Arts in the 1930s, before arthritis made it difficult for Wright to continue sculpting.

She and Goode ultimately shifted their political efforts to animal rights activism, a cause which Goode continued to support until her death in 1970. The women believed that there was a correlation between animal rights and human rights:

[They were] opposed to all injustice, including human mistreatment of animals. Feminism was, to Wright & Goode, part of a wider set of problems; animal cruelty reflected a greater barbarism leading to mistreatment of humans. Accordingly, they actively campaigned for legislation to protect animals & the environment, & lobbied the fledgling UN to include such measures. That challenge to the UN represented a unique attempt to bring animals into citizenship (Birke 693-719).

Wright helped found the National Humane Society (later renamed The Humane Society of the United States, HSUS) and the Peace Plantation Animal Sanctuary:

In 1948, Anna Briggs founded NHES. And, in 1950, with Alice Morgan Wright’s help, NHES created its first animal care facility, Peace Plantation Animal Sanctuary (Peace Plantation) [...] Built largely by Anna’s two sons, Peace Plantation operated as a safe-haven for dogs, cats, and farm animals for over 30 years [...] (The Founding of NHES).

Goode and Wright each established trusts for humane education and animal protection: the Alice Morgan Wright Trust, administered by the HSUS, emphasized the international aspects of animal welfare; the Edith J. Goode Trust, was administered by the Riggs National Bank.

In 1947, Wright received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Russell Sage College (Albany). In his allocution, the president of the College praised her activism:

Russell Sage College honors you as a talented artist and poet, and as a woman who, in spite of engrossing professional work has for more than 35 years given unstintingly of her interest and time to those organizations that recognize women's legal rights; her potentialities and her responsibilities as a citizen of the nation and of the world (Sage Colleges Libraries).

A retrospective of Wright's sculptures opened at the Marie Sterner Gallery in 1937, with a catalogue by Dorothy Stanton. Howard Devree, who reviewed the exhibition for the New York Times, called it "an arresting show." He claimed, "She is fond of the Rodinesque method of letting figures half emerge from masses and of endowing them at once with sweep and simplification" (172).

Alice Morgan Wright died of respiratory failure on April 8, 1975 at the age of 93. In 1978, the Albany Institute of History and Art organized a comprehensive posthumous exhibition of her work (1998, 160).

Artwork by Wright can be seen in several locations on the Smith College campus: sculpture in Alumnae Gym; the Doleman plaque on College Hall; and the Seelye plaque on John M. Greene porch. She is also represented in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Art and Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C., the Brookgreen Gardens in South Carolina, the Newark Museum, and the Harmanus Bleecker Library in Albany.

Sources

- “Albany Girl May Scrub Floors with Jail Suffragettes.” Buffalo Evening News, March 6, 1912, p .1. Newspapers.com.

- Albany Rural Cemetery Explorer (ARCE).

- Albany Institute of History & Art. Albany Institute of History & Art: 200 Years of Collecting. SUNY Press, 1998.

- "Alice Morgan Wright." June 1, 1947. Russell Sage Colleges Libraries.

- “Alice Morgan Wright: Artist/rebel with a cause.” The Berkshire Eagle, July 11, 2002, p. 52. NewspaperARCHIVE.com.

- Alice Morgan Wright Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA. SSC-MS-00176.

- "Alice Wright, Suffragette, Sculptor, 93." The Washington Post, April 12, 1975, p. B10. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "Alice Morgan Wright." Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- Antliff, Allen. Anarchist Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American Avant-Garde. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- “The Art Calendar.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 21, 1917, p. 22. Newspapers.com.

- Birke, Lynda. "Supporting the underdog: feminism, animal rights and citizenship in the work of Alice Morgan Wright and Edith Goode." Women's History Review, vol. 9, no. 4, 2000, pp. 693-719.

- Cable to the Free Press. "Uses Her Liberty to Go to Theater." Detroit Free Press, April 27, 1912, p. 4. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Clarke, Ida Clyde. American Women and the World War. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1918.

- Dennison, Mariea Caudill. "The American Girls' Club in Paris: The Propriety and Imprudence of Art Students, 1890-1914." Woman's Art Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, Spring-Summer 2005, pp. 32-37. JSTOR.

- Devree, Howard. "A Reviewer's Notebook: Brief Comment on Some of the Current Exhibitions - An American Expatriate." New York Times, April 25, 1937, p. 172.

- Fahlman, Betsy. Sculpture and Suffrage: The Art and Life of Alice Morgan Wright (1881-1975): Catalogue of the Exhibition at the Albany Institute of History and Art, April 21-June 11. Albany Institute of History and Art, 1978

- Fahlman, Betsy, "Wright, Alice Morgan (1881-1975)." North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge, 1977, pp. 588-589.

- Fairchild, Charlotte. “Society: The Festa in Macdougal Alley.” Vogue, vol. 50, no. 2, July 15, 1917, pp. 28-29. ProQuest.

- "The Founding of NHES - and 5 Very Special People."

- Gordon, Beverly. Bazaars and Fair Ladies: The History of the American Fundraising Fair. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

- Heung, Elsie Y. "Women's Suffrage in American Art: Recovering Forgotten Contexts, 1900-1920." Doctoral dissertation, City University of New York, 2018.

- “Leader at Smith.” The Boston Globe, March 9, 1912, p. 8. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Marconi Transatlantic Wireless Telegraph. "London Police Hunt for Miss Pankhurst: Hammerstein's Opera House." New York Times, March 7, 1912, p.1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- "May Not Aid Miss Wright: Father Says Suffragette Child is all Right in Jail." New York Tribune, March 11, 1912, p. 5. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “Miss Alice Morgan Wright, Sculptor and Suffragist.” The Wilkes-Barre Record, April 8, 1916, p. 30. Newspapers.com.

- The Morgan State House, 393 State Street, Albany, New York.

- Simmons, Eleanor Booth. “Famous Macdougal Alley Is Making Ready to Do Its Bit for the War Relief Funds.” The Sun, June 3, 1917

- , p. 7. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- The Smith Alumnae Quarterly vols. 18-19, 1926, p. 89. Internet Archive.

- Special to the New York Times. "Hope to Free Miss Wright, Parents Expected to Plead with English Authorities." New York Times, March 7, 1912, p. 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- “The Statues by Women to Help Votes for Women.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, October 17, 1915, p. 55. Newspapers.com.

- Tignetti, Catherine. "Biographical Sketch of Alice Morgan Wright." Included in Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890-1920, Alexander Street Press.