Blondelle Malone, 1877 – 1951

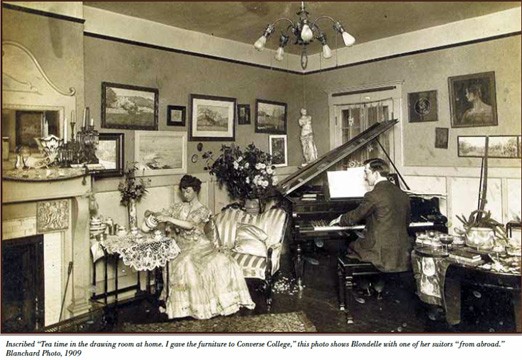

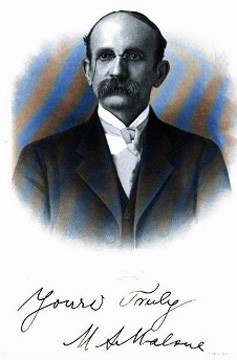

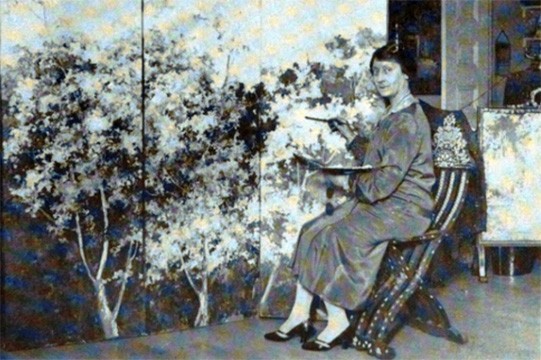

Known at one time as the "Garden Painter of America," Blondelle Octavia Edwards Malone was born in Bostwick, Georgia on November 16, 1877 and grew up in Columbia, South Carolina. Both of her parents descended from wealthy slave-holding families, and they enhanced their fortunes by running a successful music store that supplied rich Southerners with pianos. The Malones were supportive of their only child's chosen career, financing not just her education at Converse College in Spartanburg, South Carolina (she graduated in 1896), but also her training with painters John Twachtman and William Merritt Chase at the New York School of Art from 1897 – 1898, as well as her extensive world travels to Japan and Europe (Ellis). Even when he did not approve of her constant voyages, Blondelle's father faithfully sent her a monthly stipend until his death in 1930 (Washington 8).

Malone enjoyed tremendous freedom, living on her own in New York while taking classes at the Art Students League, where she befriended fellow painter (and future Girls’ Art Club resident and exhibitor) Mathilde de Cordoba (DuBose 10). She spent the summer of 1899 at an artists' colony in Cos Cob (Klacsmann 366) before traveling to California and then staying abroad continuously from 1903 to 1915, returning to the United States just once over the course of those twelve years, much to her parents' dismay (Moughan 5). A 1963 biography of Malone, drawn from her own letters and diaries, describes their frustration with her bohemian artist lifestyle: "Her parents kept urging her to come home and to think seriously of getting married and assuming the life they considered normal for their daughter" (DuBose 130).

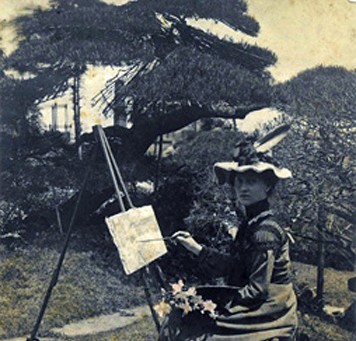

After some initial artistic success in New York (eight of her book cover designs were exhibited in 1900 by the Architectural League of New York and Charles Scribner's Sons bought two of the designs shortly after), Blondelle turned her focus toward landscape and garden painting (Moughan 5). Her great love of gardens and her prodigious talent opened doors for her in the art world and also with dignitaries, aristocrats, and socialites.

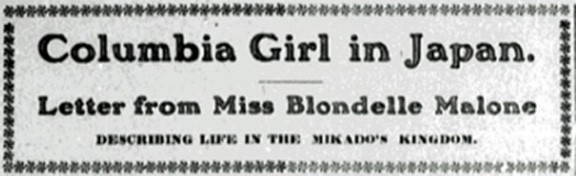

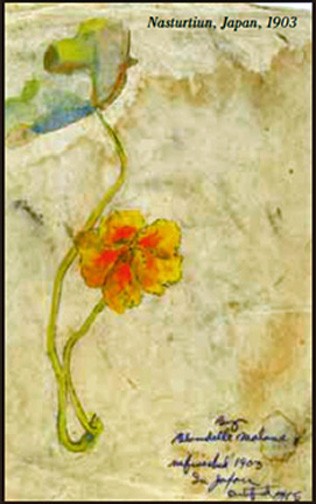

The first international adventure of Malone's life was her trip to Japan in 1903. She sailed to Yokohama on the Empress of Japan liner, accompanying P.Q. Rothrock, a former judge in the Philippines, and his wife, an amateur artist whom Malone had shrewdly befriended in California (The State, February 11, 1903, 8). She chronicled her travels in Japan for her hometown newspaper, The State (Columbia, South Carolina), in a column, "Columbia Girl in Japan: Letter from Blondelle Malone." In her September 6, 1903 article, Malone described a journey from Yokohama to Nippon, what the interior of a Japanese hotel looked like, how candied plums and Japanese tea tasted, and her experience painting the gardens around a Buddhist temple (20). Her articles, sometimes just printed letters she had written to her parents, continued into 1904, when Blondelle journeyed through India, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe, finally arriving in Western Europe for the next leg of her world tour. Blondelle painted in Venice and throughout Italy in the spring of 1904 before reaching France. In July 1904, she was in Aden, Yemen, describing camels and caravans. The next summer, in July 1905, she was in Holland, exploring Amsterdam and The Hague. Of all the extraordinary travels and experiences in Malone’s life, it was her time in France that she considered most transformative.

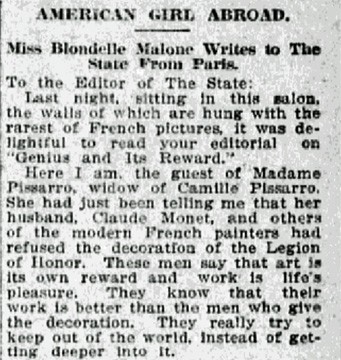

In December 1904, she visited Monet at Giverny (on the advice of fellow painter Mary Cassatt), and received his critique of her work; she later returned to paint his famed gardens. In an interview about her career published in The State in April 1922, Blondelle recalled the kindness Monet had shown her, despite his avowed dislike of Americans. “I tried to tell him I was not just working for money in painting, and I kept repeating, ‘monaie, monaie,’ and it sounded much like Monet. Then he corrected me, giving the more customary word with the French: ‘L’argent, mademoiselle’” (April 25, 1922, 10). During the same interview, Malone described her Christmas 1913 visit in Barbizon with Francois Millet and his American wife, painter Geraldine Reed Millet, who had exhibited her work at the 1906 American Woman’s Art Association show at 4 rue de Chevreuse. Blondelle counted as a close friend Julie Pissarro, the widow of her painting idol Camille Pissarro. She was also considered a protégé (and perhaps a lover) of British painter Walter Sickert, enjoyed friendly relations with portraitist Jacques Blanche, and was received more than once by Auguste Rodin, whose interest in Malone seemed to extend beyond the purely professional: "He got very much interested in me and asked if I were a virgin. 'Can't you see on my card that I am Miss Malone?' I replied. 'That signifies nothing as a rule.' 'But I am honest, if Mademoiselle is on my card, I am quite innocent'" (DuBose 106). She spent Christmas 1904 at the Giverny home of Frederick and Mary MacMonnies, in the company of Janet Scudder and Alice Jones, who would eventually become MacMonnies' second wife (DuBose 67).

Malone lived briefly in London from 1911 – 1912, exhibiting her work at the Royal Academy and also showing several paintings at the Society of American Women in London, of which Elisabeth Mills Reid was patroness. Whitelaw Reid, then U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, granted Malone permission to paint the gardens at the Reids' country estate, Wrest Park, in Ampthill, Bedfordshire. She moved back to Paris after this sojourn in the U.K., and one might speculate that it was Mrs. Reid herself who encouraged her to take up residence at 4 rue de Chevreuse in 1913.

Malone's letters and diaries do not reveal much about her day-to-day life at the Club but one anecdote does shed light on the companionship she found:

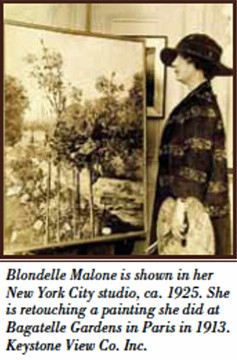

The dealers charge so much for sending pictures to the salon that I thought I would try and take them myself. Yesterday one of the best women I know, Miss [Blanche] Stanley, and I went to get two big pictures over a yard tall and a yard wide at Bagatelle. We could not find a carriage and two of the gardeners took them on their bicycles to the boat. My friend and I then took them at the nearest station to 4 Rue de Chevreuse. It rained but at last we got a carriage and got the pictures home. Today we thought we would take them ourselves to the Salon Autumn (DuBose 133).

As with many of the young American artists staying at the Club, the great triumph was to exhibit one's work and receive positive reviews. Malone was fortunate to have three separate solo exhibitions while in Paris, first at the Lyceum Club, second at the American Girls' Art Club, and third at the Galerie Boutet de Monvel, all in the space of two months in early 1914. The catalogue for the Galerie Boutet de Monvel exhibition included a preface by Maurice Guillemot of Le Figaro, who also served as president of the Société des Artistes de Neuilly (DuBose 136). Malone's Lyceum Club exhibition featured paintings from her time in London like “Crocuses in Regent’s Park,” as well as scenes from the Tuileries and Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, and other landscapes from her trips to Japan, Sicily, and Greece (H.F. 69).

Malone’s biography also recounts the favorable reception and press coverage received by her solo exhibition at the Girls’ Art Club (often described as the American Students Art Club):

Soon after the exhibition at the Lyceum, Blondelle had another at the Art Students Club. The New York Herald noted, ‘The exhibition contains more than a hundred pictures, principally oil paintings, of attractive gardens throughout Europe and some small water-colors which command attention. [...] Miss Malone came to Paris last summer after painting gardens in various parts of the world and has accomplished a great amount of work here[…]’ The Paris editor of the New York Herald carried an account, and Arsène Alexandre, the well-known French critic, noted in Le Figaro: ‘A young American artist, already noticed at Bagatelle for her beautiful spirit of painting [...] is exhibiting at the American Art Students Club landscapes full of freedom and splendor, and not lacking in delicacy and feminine subtlety (DuBose 135).

Blondelle was also a successful Salon exhibitor. Her work was featured in the 1905 Salon des Independants (8 paintings), the 1906 Salon des Independants (8 paintings), the 1911 Salon d'Automne (a painting, “The Poppy Field”), the 1911 Salon des Beaux Arts (a painting of Camille Pissarro’s garden), and the 1913 Salon des Beaux Arts, where her renowned painting of the rose garden at Bagatelle in the Bois du Boulogne was widely praised. Several of her watercolors were also displayed at the 1913 American Woman’s Art Association exhibition at the Girls’ Art Club and four of her garden scenes were exhibited at a small, private show hosted by her friend, Blanche Stanley, at a studio on rue-Notre-Dame-des-Champs in June 1914 (American Art News, July 18, 1914, 5).

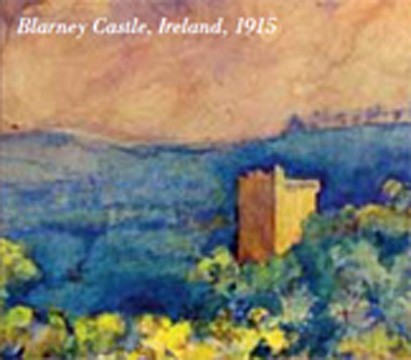

Despite her parents' wish that she return to America and marry, Malone's critical success convinced them to grant her permission to move out of the safe haven that was the American Girls’ Art Club and into her own rented studios, first at 11 rue Chateaubriand and then at 13 rue Washington, both near the Arc de Triomphe. The fact that she had sold enough pictures to pay for her own expenses surely made their decision easier. Even World War I could not deter Blondelle from pursuing a career in Europe. She fled her Paris studio at the outbreak of the war, leaving behind “several large and valuable paintings” which she hoped to retrieve when hostilities ended, but were instead shipped back to her in the United States in 1920, nearly six years after she was forced to abandon them (The State, April 27, 1915, 9). Malone spent 1914-1915 in Ireland, painting commissioned landscapes and a series of pictures of Blarney Castle (Ellis).

The sudden death of her mother in 1915 prompted Malone's permanent return to the United States. She lived and worked in Aiken, South Carolina from 1916-1919, before returning to New York in 1920. While in Aiken, Malone organized a fundraising exhibition to aid the French in 1916. She planned to sell 25 of her paintings and 25 art objects and would donate all the proceeds to “the relief fund for the wives and children of French soldier-artists.” Her old friend, Le Figaro art critic Arsène Alexandre, would safeguard the donated money and ensure it went directly to the relief fund (The State, April 20, 1916, 5). One of her biggest donors in this effort was William A. Nash, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Corn Exchange in New York, and an avid collector of Malone’s paintings - he proudly sent her a check for $100 (The State, May 31, 1916, 6).

Biographical sketches of Blondelle and her parents appeared in a 1917 book, Makers of America, and the breadth of her painted subjects is praised by the author: “From the rose gardens of California, the flowery kingdom of Japan, the Riviera, the isles of Sicily, the famed lake region of Ireland and quaint corners of Old England, Miss Malone has stolen exquisite beauty which she has reproduced with great sincerity and exactness” (497). Given her family’s Southern, slave-holding heritage, it comes as no surprise that she was a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, but her passion for Hindu philosophy and Japanese poetry, likely a result of her travels in these lands, make her a complex individual.

In the 1920s, Malone had solo exhibitions in Elmira, Utica, and Binghamton, New York, and she painted the garden of Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of the acclaimed children's book, The Secret Garden (Washington 9). Her 1922 exhibition at the Misses Hill Gallery in Manhattan was favorably reviewed; the catalogue had a foreword written by her friend and advocate, Mary Taft, art critic for The New York Times (Bowdoin 19). Perhaps reflecting on her own status as a single woman, Malone wrote a letter to the editor of The Washington Post in July 1928 describing the sacrifices women like her made when they chose careers as artists, namely that they would not marry or have children: “[…] very few women can stand the strain the severe painter’s life imposes upon them. […] The creative powers are limited, and it takes a superwoman to become the proper wife and mother and also to have the desire and ability to create inanimate beings on canvas or paper” (July 22, 1928, S2). The later years of her career were not as kind to Blondelle Malone in terms of painting sales; her Impressionist style was considered passé after WWI and her prominence in the art world began to decline.

After her father's death in 1930, Malone discovered her interest in historic preservation, purchasing and restoring the Alexandria, Virginia home of Dr. James Craik, surgeon general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and physician to George Washington. Many of her later paintings showcase Malone's love of flowering cherry trees, no doubt inspired by her close proximity to Washington, D.C. near the end of her life.

Failing health and the lingering effects of a car accident ended Blondelle's career in the 1940s. She spent her last few months in a nursing home in Columbia, South Carolina, the city she had avoided for her entire life (Moughan 6). Malone left her personal papers to the University of South Carolina and the vast majority of her works of art to the Columbia Museum of Art.

Today, a 1913 painting by Malone of the garden at 4 rue de Chevreuse still hangs over the mantel inside Reid Hall's library, connecting current students with their intrepid counterparts from the last century. It is likely that this very painting was exhibited at the Club during Malone's solo show and is one of the paintings Arsène Alexandre so aptly described as "full of freedom and splendor." (With thanks to Lisa Peters for helping us definitively attribute the painting to Malone).

Sources

- “American Girl Abroad. Miss Blondelle Malone Writes to the State from Paris.” The State, November 18, 1910, p. 4. Newspapers.com.

- "Blondelle Malone." The Johnson Collection.

- Blondelle Malone papers, SCL-MS-2743. South Caroliniana Library.

- Bowdoin, W.G. "Blondelle Malone Exhibits Gardens at Hill Gallery." The Evening World, September 19, 1922, p.19. ProQuest.

- “Columbia Artist Safe in Ireland. Miss Blondelle Malone Is Busy Doing Landscape Work in Emerald Isle.” The State, April 27, 1915, p. 9. Newspapers.com.

- “Columbia Girl at Front.” The State, April 25, 1922, p. 3, 10. Newspapers.com.

- DuBose, Louise Jones. Enigma: the career of Blondelle Malone in art and society, 1879-1951, as told in her letters and diaries. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1963.

- Ellis, Roy. "The Life and Work of Blondelle Malone." The State, July 1, 1956. Newspapers.com.

- H.F. "Studio Talk." The International Studio, vol. 52, no. 205, March 1914, p. 69. Google Books.

- Klacsmann, Karen Towers. "Malone, Blondelle Octavia Edwards." The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, volume 21: Art and Architecture. Eds. Judith H. Bonner and Estill Curtis Pennington. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013, pp. 365-367.

- Malone, Blondelle. “Columbia Girl in Japan. Describing Life in the Mikado’s Kingdom.” The Sunday State, September 6, 1903, p. 20. Newspapers.com.

- Malone, Blondelle. “In the Country of the Red Sea.” The Sunday State, July 3, 1904, p. 1. Newspapers.com.

- Malone, Blondelle. "Women Painters." The Washington Post, July 22, 1928, p. S2. ProQuest.

- Moughan, Meg. "'Paint as I See, Not as Others Paint': The Life and Work of Blondelle Malone." Caroliniana Columns, Spring 1999, pp.5-6.

- "Painting Gardens A Life of Romance." The New York Times, April 23, 1922, p. 33.

- "Paris Letter." American Art News, vol. 12, no. 36, July 18, 1914, 5.

- “Pictures Sold Net Large Sum. Miss Blondelle Malone Is Pleased with Results. French Receive Aid.” The State, May 31, 1916, p. 6. Newspapers.com.

- “Plans Exhibition to Succor French.” The State, April 20, 1916, p. 5. Newspapers.com.

- R.F. "Garden Paintings by Blondelle Malone." The Christian Science Monitor, September 21, 1922, p. 6. ProQuest.

- "To Study in Japan. Miss Blondelle Malone of This City Accompanies Friends There." The State, February 11, 1903, p.8. Newspapers.com.

- Washington, Nancy H. “Blondelle Malone: ‘The Garden Artist of America.’” Caroliniana Columns, Fall 2010, pp.7-10.

- Wilson, Leonard. "Blondelle Edwards Malone." Makers of America: Biographies of Leading Men and Women. Washington, D.C.: B.F. Johnson, Inc., 1917, pp. 495-499. Google Books.