Anna McNulty Lester, 1862 – 1900

Though certainly not a household name, Anna McNulty Lester of Rome, Georgia was one of the many young women who benefited from an affiliation with the Girls' Art Club while she was studying in Paris from 1897-1898.

Her letters and diaries were discovered many decades later by her grandniece, Susan Gilbert Harvey, a visual and performance artist who also benefited from a year abroad in Paris through Hollins College in 1957. When she discovered the contents of Anna’s trunk stowed away in her grandmother’s attic, Harvey felt that a bond united her with her great-aunt. In 1998, she decided to return to Paris for a week to retrace Anna’s experiences – a kind of 100-year anniversary pilgrimage and communion. In an interview with the Rome News Tribune, she said she had “[…] forged a spiritual link to her ancestor by reading Miss Lesters’ journals, letters and diaries that have survived for a century” (November 8, 1998). In Paris, she decided to visit all the places her great aunt mentioned in her writings, going so far as to stay on the same floor of the hotel where Lester had stayed in the fall of 1897: “[…] I requested a room on the fourth floor, thinking that perchance I would be on the same floor and have the same window outlook that she had” (Rome News Tribune), convinced that Anna’s spirit would be with her.

Harvey’s trip down memory lane resulted in a small pamphlet, Anna Lester's Paris 1897-1898, which she produced for family and friends in 2000 (RH archives). This preliminary foray led to a book, Tea with Sister Anna, featuring excerpts from the correspondence between Anna, her sister, and her parents. The book, which also includes Harvey’s own reflections on her study abroad experience, was written just in time for the fiftieth anniversary of Hollins Abroad-Paris (2005). In 2010, Harvey also wrote Postmarks: The Summers of ’98, inspired by the letters Anna and Edith wrote to their parents as they traveled through Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. These books are the main sources of biographical information on Anna McNulty Lester.

Born in Conway, South Carolina in 1862, Anna and her family moved to Rome, Georgia when she was six years old. Her sister, Edith, was born 14 years later in 1876. After studying at the Rome Female College, Anna earned a degree in bookkeeping from the Augusta Female Seminary in Staunton, Virginia, and a gold medal in drawing and painting (she had a gift for portraiture). In 1884, she studied at the Art Students’ League for one year, working under George de Forest Brush and Frederick Freer. Anna taught in several schools before being named the head of the art department of Shorter College in 1887. She stayed at Shorter until 1890, then headed the art department at Augusta Female Seminary for three years. Her sister Edith, who had graduated from Shorter College in 1894 and held a two-year post-graduate position at the Southern Conservatory of Music in Rome, was encouraged by her mentors to pursue piano and organ studies in Germany. Since their family had little money, Anna decided to subsidize Edith’s travel expenses with her own salary and real estate investments. Her 20-year-old sister left for Berlin in 1896.

Anna became disenchanted with her job as a teacher and her sister convinced her to come to Europe in 1897. Thirty-four year-old Anna sailed on July 28, 1897 aboard the SS Noordland (Red Star Line) and met up with her sister in Antwerp. They journeyed across Belgium and Germany together, ultimately spending 12 weeks sightseeing and hiking in Germany, Switzerland, France, and Italy.

Though she was more fluent in German than French, Anna decided to study art in Paris. Once there, she began to explore her rich surroundings. Her first mention of the Girl’s Art Club comes in a letter to her parents dated September 30, 1897:

I then went to The Girl's Club. You remember seeing a piece about this place in the France Journal this summer? They only had one room - and I did not like that, so the lady in charge asked me if I would like to go into a French family. I told her I would like to see the rooms. And, will you believe it, she got her hat and went with me! Was just as kind as possible. [...] now no use to get worried for Madame Higgins says if the lady at The Girl's Club recommends a place it is all right. You know at the club they only take Americans and unmarried women, so she's bound to send me to a good place. I am sure I could trust her, she had a good face. I am near to everything over there - two studios, the club, and the Franco-English guild (Tea 43).

She lived in four pensions over the course of her year in Paris, first at Lafayette House in the 16th arrondissement, then in three different locations in Montparnasse so she could be close to the art schools. Anna studied at the Académie Delécluse (under Delance and Callot) and Colarossi, where she painted “heads in watercolor from life” (Tea 133). A month before her return to the U.S., she attended the Académie Julian, which she had considered to be overrated, expensive, and snooty but which she felt was inescapable if one wanted to succeed. She also took private lessons from the miniaturist Virginia Richmond Reynolds of the Art Institute of Chicago (and the American Woman’s Art Association), whose teaching style she appreciated:

She did not flatter, and it would be useless for anyone to try that on me, for I know too well what I cannot do. But she made me feel like trying, told what was wrong and how to fix it, and what was right. She says I am doing nicely and asked me to promise not to give it up (Tea 166).

Although she spent much time working in the academies and sketching at home or in Luxembourg Gardens, she also refined her artistic eye by visiting museums and attending the varnishing of the 1898 Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where she hoped to one day exhibit. Anna also went shopping at the Bon Marché and regularly attended church services. The five charcoal drawings which illustrate Tea with Sister Anna reveal a talented artist with a desire to convey the personalities of her models through facial expressions and body language.

Though she never resided at the Girls' Art Club, Lester was grateful for the social role it played in the lives of homesick art students like her: "Do you know they have tea (English breakfast) every afternoon at the club free. Some English Lady gives it, but I haven't got the cheek to go. I went once and it was good! But I felt strange [like a] stray cat" (Tea 188).

Lester also relied on the Club for spiritual sustenance, regularly attending Sunday services at St. Luke's Chapel. In another letter to her mother and father dated October 10, 1897, she tells them:

It is only plain boards, no paint, but has stained glass windows and back of the altar a lovely piece of Tapestry, so soft and beautiful in color. If I can find a photo, I will make one when I come home. Now I am working from Life and want to do that alone while here. I never will have a better chance and you know that is what I need (Tea 108-9).

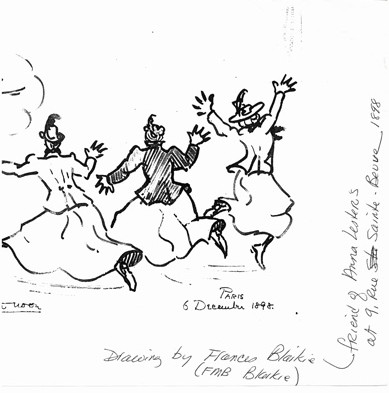

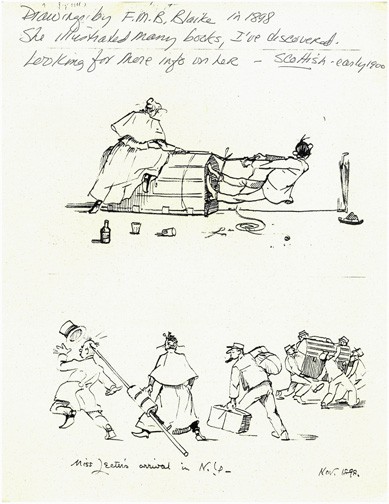

In November 1897, Lester mentions having walked with Amy Steedman and Frances Blaikie to mass from their pension at 9 rue Sainte-Beuve, where they occupied the room next to Anna’s. Steedman went on to become a prominent illustrator and children's book author, while Blaikie, a Scottish painter and illustrator, was known for her images of horses and scenes of rural life. The three became fast friends, attending church services and operas, drinking tea, and going on shopping sprees: “Their enthusiasm and vitality brightened Anna’s final weeks in Paris” (Tea 181). Anna regretted having to leave at a time she had finally made good friends in Paris, but failing health and monetary concerns were more pressing. Both Steedman and Blaikie accompanied Anna to the Gare du Nord, where she took the train to Antwerp, accompanied by Laura Berry. They boarded the SS Southwark (Red Star Line) on December 19, 1898 bound for New York. Back in the United States, Anna returned to her parent’s home and established a studio where she painted miniatures and gave private lessons. Even though her health had rapidly declined, she always maintained a cheery and bright attitude; her death was a shock to those who knew her. She succumbed to tuberculosis at the home of her parents on October 17, 1900 at the age of 38. Her obituary in the Rome Tribune evoked her last moments:

She had been in declining health for several years but during the past three months rallied from the dreaded disease of consumption, and her friends were hopeful that she might recover. Since Thursday of last week she had grown weaker and weaker, until she gradually faded away like a flower (Tea 212).

Her sister Edith, who had returned to the U.S. to teach in the music department of Agnes Scott Institute (Decatur, Georgia), wrote a letter to their parents after the funeral proposing that Anna’s tombstone be inscribed with the words “Auf Wiedersehen:”

[…] Sister’s favorite of all words used at parting. I remember when she saw it on the German tombstones she said she thought it such an appropriate and sweet sentiment. It means ‘until we meet again.’ You might just have the name and dates and this one word underneath. [It] is so simple and sweet and means so much, and she was so fond of it (Tea 212-213).

The family did just that.

Anna never married though the idea of remaining single did not appeal to her: “I don’t want to be old-maidish, and I am going to try my best not to be, but as for ‘being sweet as a violet and fresh as a rose,’ that don’t belong to me” (Tea 4).

Sources

- Fortenberry, Bill. “Ancestor’s Documents Inspire Trip to Paris. Rome News-Tribune, November 8, 1998, n.p.

- Harvey, Susan Gilbert. “Anna Lester’s Paris, 1897-1898.” Reid Hall archives, 2000.

- Harvey, Susan Gilbert. Postmarks: The Summers of ’98. Rome, Georgia: Golden Apple Press, 2010

- Harvey, Susan Gilbert. Tea with Sister Anna: A Paris Journal. Rome, Georgia: Golden Apple Press, 2005. Internet Archive.

- St John Flynn. “The Quote: James Baldwin's Paris." A Life with Culture. May 22, 2020.

- “Susan Gilbert Harvey: Author, Performer, Artist.”

- “Susan Gilbert Harvey Speaks to Chattanooga Writers Guild June 10.” The Chattanoogan, May 28, 2008.